Fri May 21 2021 · 16 min read

Rediscovering the Body: The Painful Birth of Post-Soviet Performance Art

By Varduhi Kirakosyan , Vigen Galstyan

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

“In the theater the knife is not the knife, and the blood is just ketchup. In performance the blood is the material and the razer blade or knife is the tool. It's all about being there in real time, when you don’t rehearse because you can’t do these things twice.” Marina Abramovich, 2015

Confusion and shock are typical reactions when one sees things on the stage that are no longer “acted” but presented as “real.” Strange things happen when a viewer is exposed to the spectacle of another human who plays with and through their body, using it as a tool with no restrictions of what they can do to it and how the audience can engage with it. In more than one sense, it’s a process through which the audience and the performer make the piece together.

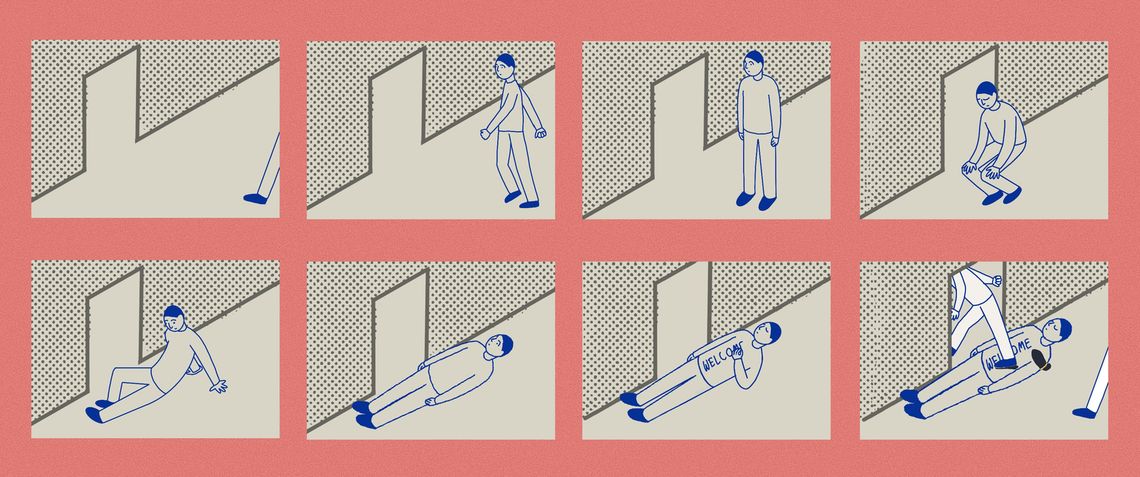

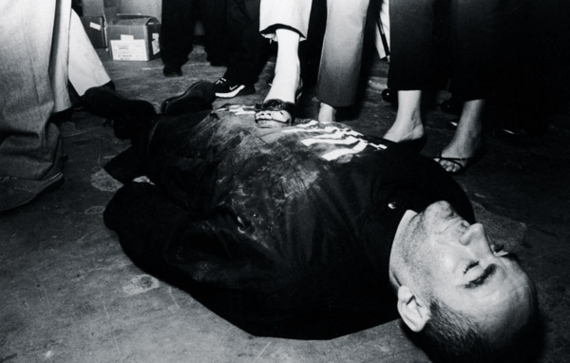

Now, imagine yourself as a part of an audience in a performance, where the artist has placed themselves as a doormat at the entrance of the gallery space. The performer executes his artwork by putting his own body under risk, pushing it to the limit of endurance. And the only way you can enter the gallery is by stepping onto his body.

Such a performance was realized for the exhibition After the Wall in Stockholm (1999), and for the 2002 Sao Paulo Biennial by Armenian contemporary artist Azat Sargsyan (b. 1965), who lay on the ground in front of the gallery entrance, using his body as a “doormat,” inscribed with the word “WELCOME.” Through this lowered status, the artist claimed that he was identifying with the Soviet Union, all of its mistakes and sins – at a moment when the remnants of the collapsed empire attempted to make contact with the outside world.

As an individual who lived through the last decades of the stagnating Union, Sargsyan was undoubtedly trying to point to the previously hidden ills and crimes committed by this country for the sake of “socialist Utopia.”

Azat Sargsyan, "Welcome" 2002.

“Such a self-critical approach by the artist grows into one of humiliation: he identifies with a doormat which somebody can choose to either walk over or use to wipe their feet on,” explained curator Eva Khachatryan. Here, the artist initiated a space of direct communication with the audience, which was “coerced” into co-authoring the artwork.

But how was this an artistic act, and how did such work challenge perceptions about what could constitute an artwork? According to art historian, critic and curator of performance art Rose Lee Goldberg’s broad definition, performance art appeared in the 1960s in the U.S. and Europe as the "avant-garde's avant-garde: Performance manifestos, from the Futurists to the present, have been the expression of dissidents who have attempted to find other means to evaluate art experience in everyday life." So-called “body art,” was a subgenre that focused on the materiality of the performers’ bodies while executing concrete actions in real time.

In Armenia, performance art emerged at the end of the 1980s, and strove to emphasize individualism and sensuality in opposition to the Soviet collective or ideological consciousness. However, it was not simply an expression of individual inner worlds, but also a critical process through which contemporary artists were re-examining the notion of the human body as a cultural and social construct. The collapse of the Soviet Union gave artists unprecedented freedom to experiment with all forms of contemporary, and more specifically, performance art. Unsurprisingly, their primary focus fell on gender, social, cultural and political issues. Through their provocative works these first representatives of post-independence Armenian art addressed concerns about the still-untested waters of capitalist culture and its ambivalent possibilities. Another aspect of the 1990s was the emergence of new technologies, such as the consumer video camera, that enabled the visual recording of time-based works. Hence, video art and performance, became two of the most popular and defining forms of “contemporaneity” in Armenian art of the time. They were also the main artistic means to open entirely novel ways of thinking about the body in Armenian visual culture at the dawn of the 21st century.

The Contemporary Art Scene in Armenia in the Wake of the USSR’s Collapse

Armenia of the 1960s-70s could perhaps be considered as one of the most liberal Republics in the Soviet bloc. An important expression of this liberalism was the publication of a new literary magazine called Garoun (Spring), which had a tremendous role in initiating direct intellectual exchanges with Western contemporary literature and art. The magazine also featured works by local avant-garde artists and placed a strong emphasis on photography as an art form. In the same manner, Garoun propagated the spread of French existentialist and post-structuralist philosophy. It was during this time, in 1972, that the art critic Henry Igityan established the Yerevan Museum of Modern Art, which was the first, and for a long time the only, modern art museum in the USSR.

In the early stages of Armenia's engagement with Western consumer culture and contemporary art practices at the end of the 1980s, the seductive promise of free expression resulted in the dominance of post-modernist methodologies and styles, of which Pop-Art, Trans-Avant Garde and Neo-Expressionism were particularly prominent. In his essay “Between Illusions and Reality,” art historian Ruben Arevshatyan explains that whether through the import of information from the West, through diaspora, or through other unofficial channels the ideological pressure was decreased to a minimum.[1] At the same time, the hippie movement which had penetrated the Soviet Union through rock music and alternative art had its followers in Yerevan, Leninakan (Gyumri) and Kirovakan (Vanadzor), and inspired the younger generation towards concrete gestures of resistance and dissent.

“By legitimizing the 'perverse' topics and images that were alien to a 'traditional', post-Soviet Armenian society and its conservatism, some artists aimed to create a relation between the national and global narratives, thereby developing a 'glocal' (global and local) context for a better, more free and more open-minded Armenia to come into being,” explains curator Taguhi Torosyan. She refers to the artistic groups, which emerged in the Perestroika period as a power that helped to give a visual and conceptual definition of ‘independence’ through art in the late 1980s and early '90s. But the 1980s also saw an increasing fragmentation of the existing bonds between artists, institutions and society at large.

With the support – or rather, lack of any direct interference – from the post-Soviet state, the Armenian art scene was free to indulge in all the creative and critical discourses popularized by the Euro-American art system. The artists were now positioning themselves as alternative to mass culture and tradition, entangling themselves in elaborate ceremonies of music, dancing at after-parties of exhibitions or home gatherings. The “nonconformists” quickly formed a new scene composed of younger artists who initiated artistic events at alternative public spaces outside of existing institutional networks. In 1987, this motley network came together in an exhibition held on the 3rd floor of the Artists’ Union in Yerevan, showing works that included almost all forms of non-realist art. This event and the group formed around it, subsequently came to be known as the 3rd Floor movement, which essentially laid the institutional foundations of contemporary art in Armenia. As noted by Ruben Arevshatyan, the movement aimed “to make a “transition from a “nonconformist-cultural dissident epoch” to the alternative artistic situation in Armenia.”

The 3rd Floor, "The Official Art Has Died- Hail to the Union of Artists from the Netherworld" exhibition, 1988.

Art Demonstration by Act Group, 1995.

One of the 3rd Floor performances was especially important in this context. It took place as part of the exhibition held at the Armenian Artists’ Union in 1989 and was known as “The Happening” or, “Hail to the Union of Artists from the Netherworld” or, “The Official Art Has Died.” The artists appeared dressed up as mummies and zombies, presenting themselves as the victims of the Soviet regime. “Dressed up as resurrected ghosts like their heavy metal heroes” the performers “crashed” the exhibition, paced around the works and left after taking photographs of themselves.[2] Through this performance they once again drew attention to the promise of Perestroika reforms, which presumed to revive the stagnant economy and attempted the “de-bureaucratization of [existing Soviet] art institutions.”[3] Such de-bureaucratization was thought of as an open and all-inclusive structure that did not delimit the artist’s choice of media, lifestyle, images, and symbols.

Historical avant-garde forms (such as the readymade object or the collage), gestures, manifestos, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art or Conceptualism became the main points of reference for these “renegades,” who were also driven by the anarchic spirit of youth culture that was experiencing a renaissance in the lead-up to the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union.

Following Armenia’s independence in 1991, a group of even younger, more radically-inclined artists called Act Group initiated a performance/public manifestation piece called Art Demonstration, which took place in 1995 in the centre of Yerevan. Act marched down Mashtots Avenue with banners bearing slogans such as: “Free Art,” “Free Culture,” “Free Creativity,” “Art Referendum,” “No Art,” “New State System,” etc. This artistic intervention was held within the framework of an exhibition called Noah’s Ark, and signified an attempt by contemporary artists to envisage the future of “national” art in the frameworks of global contemporary artistic practices.

Act Group focused more on the rising role of artivism as one of the driving forces of civil society. Having that at the core of their political beliefs, the members of the group also began rethinking the socio-political significance of the body and its instrumentalization in political processes, public manifestations, agitations and referendums.

The main theoretical and philosophical issue that was being addressed in these early performance art pieces concerned the notion of identity. The socio-political revolutions and transformations of the late 1980s led people to experience a crisis of self-representation. With the decline of the collective identity in the post-Soviet reality, there emerged an unavoidable need to define individual subjectivity in the context of a newly-formed capitalist nation state such as Armenia.

The Collective Body in Soviet Art

It is worth noting that representations of the human body in Armenian culture have always been strictly conditioned by either religious or ideological considerations. This context prepared the ground for a particularly tense and ambivalent treatment of the body in the emergent field of contemporary Armenian art. More specifically, it had to deal with the powerful legacy of the Soviet art, which placed a unique emphasis on the working body as part of the Soviet collective.

The rhetoric of socialist-realist art served to transmit a sense of collectivity in opposition to individual experience. Soviet artists did not praise the beauty of the body, but its ability to perform feats of physicality. At the dawn of the 20th century, ideologists of Communism drew on Marxist theories to postulate the notion that Man will make it his purpose to master his own emotions, to lift his instincts to the heights of consciousness, in order to raise himself to a new plane, towards a higher socio-biologic form. This New Man – or “Superman” – who was meant to be the ideal worker, the ideal soldier and the ideal citizen embodied the glorification of industrial labor, which in turn, came to dominate the spectre of official Soviet art for much of the latter’s existence. The socialist body, therefore, was construed by Soviet artists as a generally homogenous, “modular” figure that was either working or marching in urban or industrial settings, instead of engaging in more personal experiences of corporeality. Though this situation would change dramatically following the end of Stalinist dictatorship in 1954, these ideological imperatives remained prevalent in one way or another until the Glasnost era in the mid-1980s.

Kamo Nigarian, untitled performance, 1987.

In Soviet visual culture, people rarely appeared in their intimate environment outside of portraiture, and almost never in situations that would pit them against the prevailing social order. They were usually shown either armed with an instrument or involved in some kind of labor. The notions of a person and a worker were interchangeable in this equation: the human is the one who works. Treatments of the subject of the “body” in Armenian artists' works also followed these iconographic and intellectual doctrines. However, there was also a clear need to resist the eradication of individual psychological space, as evidenced by the works of interwar Armenian modernists painters like Mariam Aslamazyan, Alexander Bajbeuk Melikyan and, especially, Yervand Kochar. By the end of the 1970s, subsequent generations of modernists such as Ruben Adalyan, Henri Elibekyan, Lavinia Bajbeuk-Melikyan, Kamo Nigarian, Varujan Vardanyan as well as sculptors Arto Tchakmadjian, Ara Shiraz and others, would make the topic of the “suffering” or “exalted” body into a key subject of their oeuvre, thus paving the way for its deeper exploration in post-independence performance art.

The Emergence of the Subjective Body in Post-Soviet Performance Art

The disappearance of an entire civilizational order couldn’t occur without any consequences. Hence, the collapse of the USSR gave birth to yet another widespread motif of the body. With the decline of industrial and utopian societies, came a new type of citizen who was now free and flexible in their choice of social constructs, roles and images. But such sudden freedoms also brought with them radical ambivalences that continue to plague post-Soviet nations to this day. The loss of the structures that provided relative stability and security for much of the 20th century (even those that limited one’s individual freedom) brought issues of identity to the forefront of debates surrounding the as-yet vague understandings of what it means to be human in a globalized, consumer-driven world.

Hamlet Hovsepian, Yawning, 1975. Still from filmed performance.

Grigor Khachatryan, the Grigor Khachatryan Prize given to Nikol Pashinyan, 2000.

The first engagement with performance art as a distinct artistic medium occurred in Armenia as early as 1975 in the filmed performance pieces by Hamlet Hovsepian (b.1950). In works called “Yawning,” “Itching,” “Thinker” and so on, Hovsepian explored the anarchic possibilities of a non-social or “empty” identity by focusing on primal physical actions without any narrative or ideological imperative. But it was only in the late-1980s that performance art came to the fore in the local context. The conceptual artist Grigor Khatchatryan (b.1952) came up with many performances and actions, which parodied social and governmental systems and glorified the individual. The artist himself appeared as the personification of the conceptual methodology, which allowed the person to evade an identity reduced to a body and a name. “You are not men, you are the contemporaries of Grigor Khachatryan”, or “I am not a man, I am Grigor Khachatryan,” said the slogan of Khachatryan’s most famous work, in which the artist literally presented himself as a “prize” to elect recipients. Ceremonies with awards, speeches and statements are the instruments of a personality cult devoted to the artist by the artist.

“The prize in the Soviet system just meant that ‘Soviet people’ and the Communist Party appreciated the art of the artist. It didn’t mean that the artist was above other people, on the contrary, the award-winning was accompanied by personal humiliation, putting stress on the fact that the artist was an ordinary man,” explains art critic Vardan Jaloyan. Thus, the actual “winner” of the prize was the people and the Party, which made the artists in that exchange into a servant of sorts – an instrument of the state. For Grigor Khachatryan, the prize was the existence of the artist himself as an embodiment of a trans-social, anarchic entity that came closest to the notion of total liberty, and hence, total control over one’s own subjectivity. The artistic “I”, thus, became the new “Ideal,” which the artist was free to bestow upon others, in lieu of any other Utopian paradigms or collective belief systems. In this equation, the body was not so much the embodiment of this selfhood, but a container for it – a tool, which could be manipulated and reshaped as the artist saw fit.

Despite Khachatryan’s enthusiastic validation of the artist’s “superior” autonomy, many of the performative artworks of the 1990s–2000s revolved around the concept of the useless and the wounded body, which was tied to critique of institutional repression. This attitude became especially prominent with the foregrounding of “physicality” and concepts of privacy in contemporary Armenian art, which was due to the disappearance of the collective body and the transition to consumer culture.

For the first time ever, the private, individual bodies of artists were now separate and free from the “whole.’’ That this was an issue of momentous significance is testified by the simple fact that the word “privacy” or the philosophical notion of the individual “subject” had no linguistic equivalents in Armenian. In the context of weakening of social institutions such as the school, the family, the church and the state, the figure of the lone individual gained more prominence and also became more vulnerable as a result. The private seemed to reflect the wounded parts of the whole: the truncated and fragmented post-Soviet body.

Azat Sargsyan at Yerevan's Freedom Square.

One of the artists whose work explored these thorny issues in the first decades of independent Armenian art is Azat Sargsyan (b.1965). Through his live performances, Sargsyan addressed the problematic nature of freedom in Armenian society. In one of his performances held on State Independence Day, the artist hung himself from feet in Yerevan’s Freedom Square. The performance embodied the idea of the body as both a physically and emotionally wounded entity. It entailed a tautological wordplay, where a man with the name Azat, which means freedom and independence in Armenian, hangs himself in Freedom Square on Independence Day in conditions that completely confound and destabilize that very same notion. According to Taguhi Torosyan, the rupture was the artist’s body position: hanging upside down, it invoked “the image of the Hanged Man in the Major Arcana of Tarot cards, standing for sacrifice, letting go, surrendering, passivity, suspension, acceptance, patience, contemplation, inner harmony, conformism, non-action, waiting, and giving up.”

In more than one sense, the artist suggested the impossibility of “total” agency as a starting point for renegotiating the conditions of individual identity within a capitalist nation state.

In the first section of his 2002 three-part performance Azatapolitanas, Sargsyan placed himself as a doormat at the entrance of the gallery space wearing a black tunic stenciled with the word “Welcome.” As noted by art historian and curator Neery Melkonyan, “Through this bold re-enactment of vulnerability Sargsyan makes us question the effects of institutional practices that fix cultural objects/subjects into hierarchical categories.”[4] With the second part of his performance, Sargsyan directed the viewers’ attention to themselves by attaching a mirror on his back and crawling through the exhibition space, his feet bandaged. All that the viewers were expected to do was to recognize themselves by looking in the mirror. Sargsyan’s attempt at self-recognition is also evident in the third part of the performance entitled “Help Me,” where he stood in the exhibition space, bound in bandages, waiting for visitors to set him free.

In this performance trilogy, we can see the narratives of suffering and endurance interwoven into what Sargsyan described as his iconography of a “personal metropolitan.”[5] These pieces seem to be attempts and exercises of knowing oneself, where the ultimate freedom might be attained only through a total understanding and acceptance of one’s own fallibilities and weaknesses. Hence, the “free” individual is not the one that achieves supremacy and infallibility (i.e. the Superman of the Soviet visual culture), but one that acknowledges their limits, fragility and utter dependence on the “Other” or, to be precise, their humanness. However, “The personal geography that Sargsyan maps out for us through his own body does not exclude the political,” as Melkonian states. She assumes that the artist's first name meaning “freedom” in several ancient Near Eastern languages, might suppose that “Azatapolitanas also symbolize the endurance that is associated with the pending geopolitical predicament – the turbulent history and the fragile destiny – of Sargsyan's native land, Armenia.”[6]

That turbulence and state of uncertainty was reflected in the inconsistent and erratic development of Armenian performance art. Following a certain “boom” in the 1990s and early 2000s, performance-based art became increasingly preoccupied with what Nazaret Karoyan describes as “the discovery of one’s own body” and its “primeval” essences outside of the repressive social mechanisms. By exposing and negating these oppressive orders, performance artists wanted to critique fixed perceptions of national, individual, gender or sexual identity and define more fluid and non-binary ways of being. The figure/body of the artist, became an emblem of a trans-societal experience that existed outside of the political processes, which delimited the role of the individual within the wider social spectrum. This was a tendency that was particularly prominent in the work of feminist and queer performance artists, such as Diana Hakobyan, Anna Barseghyan, Sona Abgaryan, Astghik Melkonyan, the Queering Yerevan collective, Raffie Davtian and others.

While their questioning of Armenia’s parochial cultural structures played an enormous role in expanding the intellectual discourses around ideas of the body, these tendencies also led to rather unfortunate consequences, namely – the isolation of the artist as a cultural agent, and their alienation from socio-political processes. Trapped in a cul-de-sac of narcissistic self-examination, the socially-disengaged body of the contemporary artist gradually lost its relevance in the public sphere. This condition was patently demonstrated by the fact that most of the performance pieces created during the late 2000s and early 2010s were made for the video camera, in the privacy of the artist’s studio. While many of its aspects survived in video art or activist interventions (such as those realized by the group Art Laboratory), it could be argued that by the mid-2010s, performance art had practically disappeared from the Armenian contemporary art scene as an autonomous medium.

Nevertheless, performance art had a profound impact in changing perceptions of the body in Armenia’s post-independence culture. Using themselves as tools and objects of critical investigation, Armenian performance artists made the body into a vital subject of artistic enquiry and placed it in a nexus of politically-charged debates around individual, national and modern identity. The legacy of these pioneering figures continues to inform new work by younger generations of contemporary practitioners, who are again turning to the “disruptive” power of the body and performance art, as an effective tool in critical examinations of current realities.

----

[1] Ruben Arevshatyan, “Between Illusions and Reality,” in Hedwig Saxenhuber (ed.) Adieu Paradjanov: Contemporary Art From Armenia, Springerin, Vienna, 2003, pp.2-5.

[2] Angela Harutyunyan, The Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the ‘Painterly Real’, 1987–2004, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2017, p.59.

[3] Ibid., p.52.

[4] Neery Melkonian, “Azat Sargsyan: Azatapolitanas,” in Alfons Hug (ed.), Catalogue 25th Bienal de São Paulo, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2002, p.56.

[5] Idem.

[6] Idem.

Et Cetera

Notes From a Future Museum: The Aesthetic Politics of Armenian “Chekanka” Art

By Vigen Galstyan

Hybridizing fine art and mass culture, Soviet-era “chekanka” art generated an unconventional visual world in which ancient and modern mythologies, as well as sexual and political desires could be blended into a patently local cultural narrative.

Back to the Future: The Evolution of Post-Soviet Aesthetic in Armenian Fashion

By Anais Gyulbudaghyan

The Armenian love for following trends is something that is a part of the collective cultural and political history. And that tendency became stronger after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“Where Are You, Soghomon?” Arman Nshanian’s Melodrama About Komitas

By Sona Karapoghosyan

“Songs of Solomon” promises to tell the story of young Komitas but ends up disappointing as the direction drastically changes, turning into another tragic film about the Armenian Genocide and Komitas simply a faded symbol emphasizing a lost culture and history.

“Return the Tramway to Yerevan:” About Aram Pachyan’s Novel “P/F”

By Tigran Amiryan

Literary theorist Tigran Amiryan takes the reader on a journey into the essence of Aram Pachyan's experimental novel "P/F", noting that while it might not appeal to aficionados of fictional prose it will cause an unquenchable thirst for contemplation.

Escaping to Cafes: Yerevan’s 2021 Gastronomic Trends

By Ella Kanegarian

In the past several years, residents of Yerevan have started spending more time in cafes and the outdoors generally. We eat out, take our breaks, work and escape from the cares of our daily lives.

Listening to Imagine: A Post-Crisis Exhibition Attempting to Reimagine Armenia’s Future

By Liana Sahakyan

The ongoing crises in Armenia are forcing old ideas about the future to crumble, making way for as yet undefined horizons. In this process, contemporary art tries to intervene to create new spaces for imagining the future.

Notes From a Future Museum: Time-Keepers

By Vigen Galstyan

Vigen Galstyan explores the humble charm of Soviet Armenian mechanical clocks in this first instalment of a series of articles about Armenia’s not-too-distant past as a major producer of everyday consumer goods and a hot spot for industrial design in the USSR.