Sun Mar 21 2021 · 6 min read

“Where Are You, Soghomon?” Arman Nshanian’s Melodrama About Komitas

By Sona Karapoghosyan

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Director Arman Nshanian's feature film Songs of Solomon will hit the screens this March - a few months after it was submitted as Armenia’s entry to the Oscars’ “Best International Feature Film” category by the Armenian National Film Academy. The film was not included in the recently published shortlist for the category, although one of its nine co-producers is the Oscar-winning producer of Green Book (2018), Nick Vallelonga.

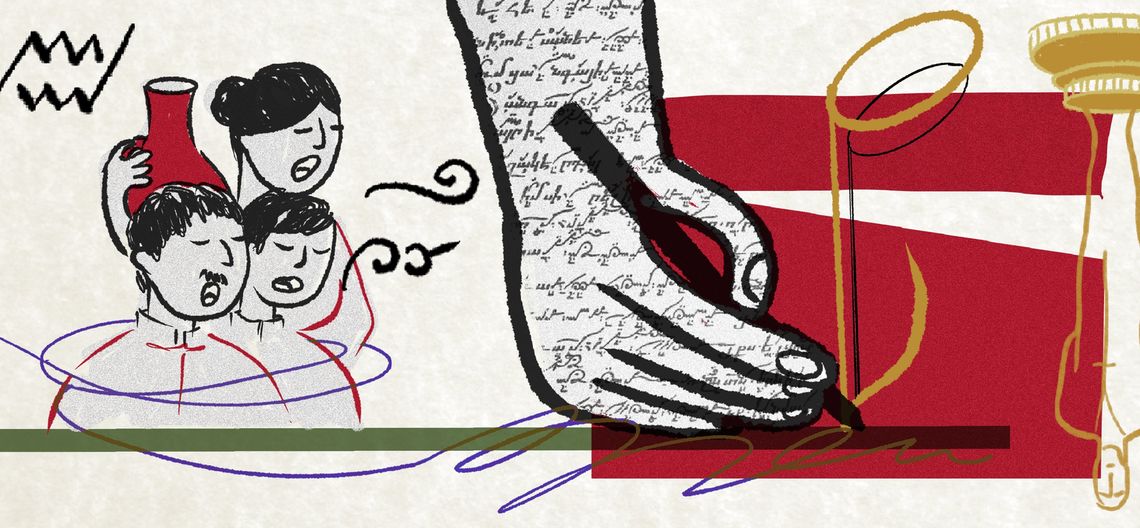

Songs of Solomon starts as a fairy tale that promises to tell the story of young Komitas and his two friends, Sona (an Armenian) and Sevil (a Turk). The children reside in Komitas’ birthplace Koutina (Kütahya) during the years of Abdul Hamid’s rule (1890s). The story is told through Sevil’s point of view. Thirty minutes in, the direction of the storyline drastically changes, turning into another tragic film about the Armenian Genocide. Komitas simply becomes a faded symbol used to emphasize the pain of a lost culture and history.

Still from the movie trailer.

Komitas’ character is not new to art. Many have seen the personification of the tragedy of the Armenian Genocide in this character: from literature (Paruyr Sevak) to fine arts (Yeghishe Tadevosyan, Panos Terlemezian, Grigor Khanjyan) to contemporary film (Grigor Melik-Avakyan, Don Askarian, Vigen Chaldranyan). It is interesting that Komitas never appears as a tangible individual in the film; he is a constant imaginary metaphor, a phantom. Arman Nshanian’s Komitas is also incomplete and distorted. Despite having obvious biopic aspirations, the director fails to fully develop the priest’s character. At the beginning of the film, the latter is portrayed like a Marvel superhero gifted with supernatural qualities - a divine voice and hearing that allows him to hear melodies from a few kilometers away, or to perform the hymn he has heard only once with absolute accuracy. But in the second half of the film, this plot line disappears. The blind grandmother's prophecy that an unimaginable journey and future awaits the “orphan” is fulfilled beyond the screen, leaving the audience to complete the story at the expense of their own imagination and knowledge. Nothing is said about how Komitas collected and saved the Armenian khaz system of musical notation, and gained recognition in Berlin, Paris, Geneva and Cairo. We meet Komitas after the completion of his studies in Etchmiadzin and Berlin, during his last concert in Istanbul. The role of Komitas is portrayed by Samvel Tadevosian, but due to the fading effect used on his face, the actor is almost unrecognizable and arguably marginalized.

Still from the movie trailer.

If we try to compare this portrayal of Komitas with the protagonist in Vigen Chaldranyan's Alter Ego (2015), who is also mythologized throughout the film, we would notice some clear differences. Chaldranyan uses Komitas as a ghost, who is either pursued or who himself pursues the film's other characters. The director continuously questions allegations about the priest. Meanwhile in his film, Nshanian presents his point of view about Komitas the person. Unlike Chaldranyan, Arman Nshanian makes no attempt to unravel the mystery of Komitas' silence, which is present in Songs of Solomon even before the priest’s appearance in the psychiatric hospital.

Another interesting example of presenting the memory of the Genocide with a pivotal artist at its center is Atom Egoyan. His Ararat tells the story of another great Armenian intellectual, Arshile Gorky, but uses an alternative way to weave the narrative. Despite the fact that no hard facts about Gorky's biography are mentioned in the film (and in general, everything in Ararat is subjected to constant questioning), Egoyan tries to explore Gorky through his characters, by projecting Gorky’s connection with his mother onto his two contemporary protagonists - Ani and Raffi - and their relationship. The director also uses the same method to discuss historical facts.

All the atrocities and barbarities that took place during the Genocide are movies within a movie in Ararat, filmed by the "famous director E. Saroyan" (played by Charles Aznavour). This way, Egoyan absolves himself of the responsibility of presenting or distorting historical facts. Whereas Saroyan, representing a generation of Genocide survivors, who perceives reality only on the level of emotions, is free to not care for historical accuracy in his own film, by ignoring the fact that Ararat is not visible from Van. How can a film about the Genocide not include Ararat?

In a sense, Songs of Solomon is similar to Edward Saroyan's film within a film, which represents the emotional reflection of intergenerational horror stories on screen. Nshanian does not try to insert any historical accuracy in the film; in one of the first scenes, he puts forward the false argument that, until the Hamidian massacres, Armenians and Turks lived in peace and harmony. Meanwhile, in the following shots, Turkish children address Solomon and Sona with racist expressions and insults. All of the director's efforts to appear objective are limited by the “progressive Turkish” characters who resist the atrocities committed against Armenians but can do nothing about their bloodthirsty leaders. Arman Nshanian himself portrays the role of one of these leaders, Osman.

Adhering to the philosophy of Orientalism, the director has tried to recreate the colors of the Ottoman Empire - the everyday life of citizens, the Eastern market, the costumes - but the result is superficial and sterile. References to famous works of literature and film are made in the movie; however, they do not serve their purpose. Some of the scenes shot in the monastery are reminiscent of Parajanov's The Color of Pomegranates, but instead of enriching the visual experience of the film, they highlight the commonness of Komitas' character - in contrast to Parajanov's Sayat-Nova. The title of the film, on the other hand, refers to the biblical book, Song of Songs (sometimes also called Songs of Solomon), and to Tony Morrison's novel, Song of Solomon, but having no general connection with either of these works makes this intertextual association almost meaningless. Komitas' music is played throughout the film, but except for the performance of "Shushiki," an audience who is unfamiliar with the works of the priest is not introduced to their creator.

The cinematography of the film is also very contradictory. The director of photography, Anthony Rickert-Epstein, who has a large repertoire of thrillers, has invested all of his experience in Songs of Solomon. Slow motion scenes and sound effects accompanied by zoom shots make the mysterious veil around Komitas’ character even messier. The computer graphics of the film are also weak, and often distracting. The applied effects (and their recurrence) are noticeable even to the naked eye.

Songs of Solomon is Arman Nshanian's first full-length directorial debut. Prior to this, he had shot one of the music videos for the band System of a Down and acted in a number of films. Nshanian is also an operatic tenor and has performed beautiful renditions of Komitas.

The film was planned to hit the big screen in April 2020, ahead of the 105th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. However, due to the outbreak of the pandemic and the closure of movie theaters, it is being presented to the Armenian public a year later, now in a post-war context. Watching the film amid a new reality, when we are feeling an urgent need to review our historical trajectory, Songs of Solomon comes across as more than outdated. For nearly a century, we have been told about dignified and hard-working Armenians who were killed by bloodthirsty Turks, but have not been offered any exit plan - except from self-pity and infinite pain that is passed down from one generation to another. The same mistake is being made today. Instead of looking for and correcting mistakes, and becoming conscious of our own guilt, we are living and experiencing the same pain of loss; we are afraid of moving forward. Songs of Solomon and all similar films should serve as an example for us to re-evaluate the past and to find the strength to live again. After watching the film, we should not feel sorry for ourselves, but continue to preserve what we have and to create anew. Unfortunately, this film didn’t take us there.

etc.

“Return the Tramway to Yerevan:” About Aram Pachyan’s Novel “P/F”

By Tigran Amiryan

Literary theorist Tigran Amiryan takes the reader on a journey into the essence of Aram Pachyan's experimental novel "P/F", noting that while it might not appeal to aficionados of fictional prose it will cause an unquenchable thirst for contemplation.

Listening to Imagine: A Post-Crisis Exhibition Attempting to Reimagine Armenia’s Future

By Liana Sahakyan

The ongoing crises in Armenia are forcing old ideas about the future to crumble, making way for as yet undefined horizons. In this process, contemporary art tries to intervene to create new spaces for imagining the future.

Escaping to Cafes: Yerevan’s 2021 Gastronomic Trends

By Ella Kanegarian

In the past several years, residents of Yerevan have started spending more time in cafes and the outdoors generally. We eat out, take our breaks, work and escape from the cares of our daily lives.

Notes From a Future Museum: Time-Keepers

By Vigen Galstyan

Vigen Galstyan explores the humble charm of Soviet Armenian mechanical clocks in this first instalment of a series of articles about Armenia’s not-too-distant past as a major producer of everyday consumer goods and a hot spot for industrial design in the USSR.

Comments

Taline Voskeritchian

9/13/2021, 2:44:56 PMTaline Voskeritchian Sona Karapoghosyan has written a thoughtful review of Song of Solomon, doing the kind of criticism that we don't see much in our written media--analytical, fair, and thoughtful. There was one other write-up of this terrible film in a diaspora community newspaper that was so uncritical as to be embarrassing in its revelry of the possibility of an Oscar for this film. I won't be surprised when March comes around, similar laudatory write-ups will appear in our newspapers. Karapoghosyan's review is a corrective spark.