Thu Apr 29 2021 · 12 min read

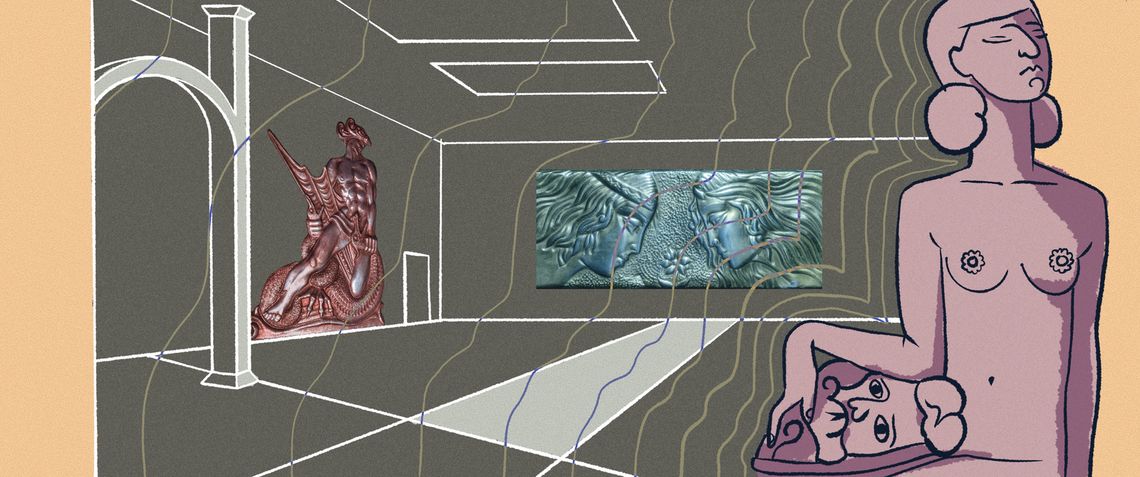

Notes From a Future Museum: The Aesthetic Politics of Armenian “Chekanka” Art

Chasing Fantasies and National Desires

By Vigen Galstyan

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

1960s

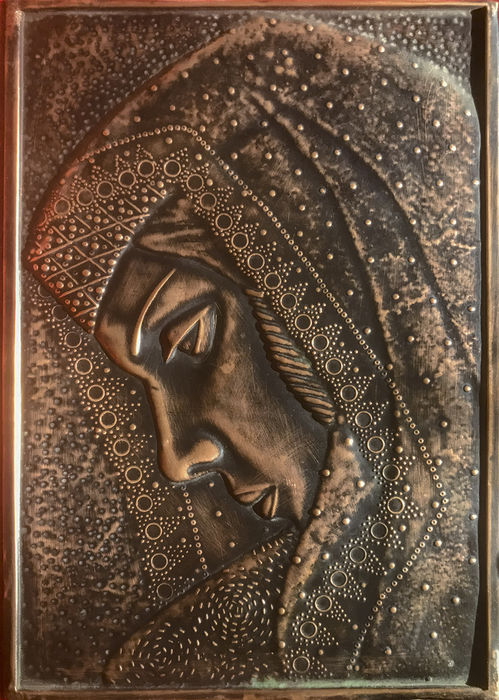

Mikael Arutchyan, Salome.

<hapPy FacE>

1970s

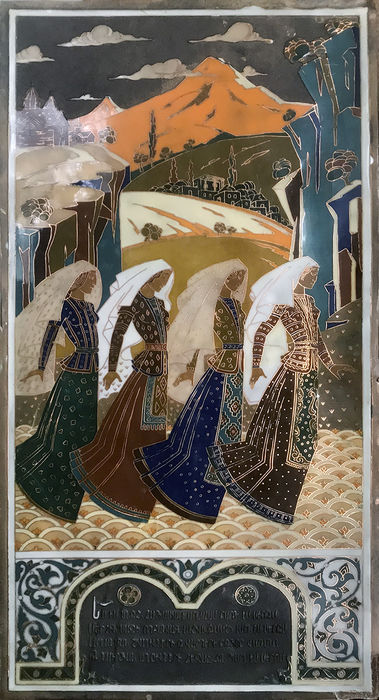

Armenian souvenir factory, Artashes and Satenik

Komitas.

Armenian Souvenir Combine, Boy Playing the Flute.

Fine Art Combine. Vahagn.

Combine of Folk souvenirs. Spinning Thread.

1980s

Images from the author's personal collection.

There was no pornography, no pop-stars and no comic books in Soviet Armenia. But there were chekankas.[1] For at least four decades, these copper wall-panels decorated the homes of ordinary Soviet citizens en masse, and were particularly prized in Armenia as tokens of aesthetic emancipation. Since censorship made it impossible to trade in items of religious devotion in the USSR, the chekanka also became a proxy for expressing a sense of shared identity and belief in collective mythologies. As the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy has proposed, such mythologies are essential for the formation of all communities and seem to be always underpinned by feelings of loss.[2] Imbued with longing for a perpetually lost ideal, these collective narratives still shape modern ideas of nation and state. It is no wonder, then, that the emergence of mass-produced chekankas coincided with the awakening of nationalist discourses in Armenia and the Caucasus during the 1960s.

The Soviet chekanka used the metal-chasing or Repoussè technique that has been known to craftsmen and artists since early antiquity. Traced from a pre-existing mold, a thin sheet of metal was hammered into a relief, which could then be manipulated into different shapes – from giant statues to manuscript covers. A magnificent example of local Repoussè work is the 2200 BC silver goblet from Karashamb's royal tomb, along with icons of modern art, such as Yervand Kochar's 1959 statue of Sasuntsi Davit, in Yerevan. Few, however, were aware of, or cared about these historical connections when they selected a chekanka to hang on the wall. Often, one didn't even have that choice, as the chekanka became one of those popular “all-occasions” presents, which one was forced to display as a form of appreciation.

The various art funds or khudfonds (state-run craft workshops), which produced chekankas, ensured that there was a broad range of themes to suit every occasion. Thus, turning over a vintage plaque of a semi-clad “Aghtamar” – the sexually brazen, but tragic heroine of Hovhannes Tumanyan's eponymous poem – we're likely to find a dedication “To Grandpa, on his 70th anniversary” or an ode “To our dear chemistry teacher, Ms. Sargsyan, on the occasion of her retirement,” penned on the back of a young couple, leaning over for a passionate kiss. Such schmaltzy ubiquity has, ironically, led to the complete exclusion of this art form from discussions of post-war Soviet-Armenian modern art, and its relegation to the realm of “plebeian” culture.[3]

But the appearance of the Armenian chekanka was not just an endeavor in peddling maudlin souvenirs. The emergence of this new craft during the 1960s was also due to a distinct socio-cultural development: the commodification of Armenian cultural heritage as a resource for the local light industries. Lacking the historical trajectory of European imperial and avant-garde industrial design, the “pubescent” Armenian manufacturers of household goods had to rely on ancient and medieval heritage for inspiration and, what we'd now term as content. Consequently, the chekanka became a novel and popular format through which the “national” imaginary could manifest and categorize itself. Cost-effective and quick to produce, the medium was embraced by the entire spectrum of the creative industries – from amateur and professional artists, craftsmen and architects to product designers. By the 1980s, the chekanka was, in effect, the most visible and ubiquitous form of decorative art in Armenia. Besides the walls of ordinary households, it also decorated most cafes, shops, administrative buildings and had a dedicated store in the center of Yerevan.

Visitors to the chekanka salon on Sayat-Nova street could find an extensive catalogue of well-known motifs, which included key figures, views and events that marked the outlines of modern Armenian cultural identity. Mythical heroes like David and Mher from the epic Sasna Tsrer, echoed Vahagn – the pagan god of victory – or the great kings of antiquity, Argishti and Artashes. These male protagonists were joined by a troupe of female counterparts. Mostly drawn from literary classics, these embossed heroines comprised a narrower range of models and ideas. The “girls” were decked-out to be romantic objects of desire (Aghtamar, Satenik, Anush), etalons of virtue (Mother Armenia, Parvana, The Thread-Spinners, sometimes Aghtamar too), alluring femme-fatales (Salome, Aghtamar frequently) or victims of social oppression (Maro, and, in some interpretations, Aghtamar as well).

The psychosexual connotations behind these various types and motifs are, today, apparent to the naked eye. Yet, for the average Soviet-Armenian citizen who simply wanted some visual sparkle for the dour kitchen walls or the drab Khurschovka (prefab 1960s Soviet housing) hallway, the copper plaques were primarily an innocuous means of fulfilling decorative tastes or affirming a sense of national belonging. Thus, the blithe unconsciousness about the barely-veiled erotics of the chekankas is what fuels their appeal – long after they were relegated to attics and garages, as testaments of Communist kitsch.

Kitsch, of course, was a distinct byproduct of the industrial revolution, as argued by art historian Clement Greenberg, who saw it as the antithesis to the high philosophical aspirations of modernist art.[4] Exaggerated, maudlin and gaudy, the expression of kitsch was intrinsically tied to conditions of mass production and affordability, which pandered to people's basest ideas of what is beautiful or inspiring. Emerging relatively late in Armenia, the camp sensibility of industrially-produced goods didn't have the extensive legacy and finesse of their Euro-American counterparts. Relying more on crude melodramatics and sentimental charm, the chekanka was a “primitive” object that posed no threat to the self-righteous seriousness of the Soviet cultural establishment.

Ironically, kitsch came to fill the place of avant-garde modernism in the USSR, when the latter was eradicated by Josef Stalin in the mid 1930s (see The Exhibition of Achievement of National Economy complex in Moscow for a demonstrative example). And even though Stalin's cultural doctrines were rescinded in the late 1950s, they left a strong trace on the popular imaginary. The method through which Stalinism engendered memorable signs and images recognizable to millions of people from different backgrounds, was a well-oiled mechanism that remained in use long after the dictator's death. Reality could be condensed into broad symbols that propagated a singular ideology, ie: Stalin as a higher being, USSR as utopia, or actress Lyubov Orlova as the socialist “Madonna.”

Having significantly shifted its ideological (and aesthetic) horizons by the 1960s, Soviet mass culture turned to kitsch as a way of exploring nostalgic invocations of history, idealizations of pre-industrial pastoral lifestyles and, more furtively – revivals of nationalist desires. The massive souvenir industry, which sprung up on the back of these tendencies around the USSR, was particularly conducive for transmitting coded ideas about national self-representation. It is unsurprising that, despite their production in almost all the USSR republics, the chekanka was taken most seriously in Armenia and Georgia – two of the smallest states, which were aggressively asserting their cultural differences within the socialist space. Looking at the phenomenon in the Georgian context, art historian Paul Manning notes that "the chekanka world in the 1960s and 1970s created a kind of secular mythology of the nation, which flattened out differences between genres of myth, legend, folklore, history and fantasy, to produce a kind of timeless daydream ‘elsewhere’ of the national essence, opposed to the workaday world of socialism."[5] The importance of this interior or imaginary “elsewhere” for the burgeoning Armenian souvenir industry is apparent in the commitment towards aesthetic quality and “meaningful” narratives, which both the Georgian and Armenian chekankas powerfully display.

The first range of copper panels in Armenia was released by the Yerevan Fine Art Combine, and relied on famous works of modern Armenian art by Hakob Gurdjian, Hakob Kodjoyan, Alexander Ter-Marukyan and Martiros Saryan. Even the “re-design” of the original images was done by notable artists, as in Mikael Arutchyan's rendition of Gurdjian's sultry 1925 sculpture of Salome. The chekanka, thus, served an important democratizing function. It “domesticated” fine art not through cheap mechanical reproductions, but via affordable, new art objects, which aimed to elevate the public's cultural affinities and instill the concept of “national” art within the wider social spectrum. To achieve this, the chekanka drew from the vocabulary of “archaic modernism” – a stylistic movement concerned with both formal and spiritual dimensions of art, which emerged in the 1960s as the main rival to Soviet socialist-realism. Hence, the direct allusions to traditional and experimental aesthetics enabled the chekanka masters to easily transform monuments, landscapes, people and historical events into venerable imagery for the space-age home.

The notion of veneration is the underlying philosophy behind all objects of mass or pop culture. Similarly, what we see in the Armenian chekanka is a response to the collective demand for emotionally resonant images of faith, which had been ousted from the Soviet visual culture by the overtly dogmatic (and secular) iconography of the Communist Party. What the post-WWII souvenir industry endeavored to do, instead, was to generate symbols that connected people on a more humanistic level, while providing an avenue for romantic escapism. The chekanka fitted this task perfectly. It could transform almost any subject into a talismanic icon for the home: a “folkloric” variation of pop art. What got converted in this process were not just the mythopoetic heroes and heroines. Equally important as resistance to the language of socialist propaganda were the series of wall-plaques featuring historical and modern Armenian cultural figures – an aspect of chekanka art that has few parallels outside of Armenia.

Using personages already entrenched in the popular imagination, this group of portraits included idealized representations of alphabet-inventor Mesrop Mashtots, medieval theologian-poet Grigor Narekatsi, the 18th century bard Sayat-Nova and giants of modern Armenian literature – Hovhannes Tumanyan, Avetik Isahakyan, Paruyr Sevak and Hovhanness Shiraz. Even contemporary sport legends like Olympic champion Yuri Vardanyan and chess maestro Tigran Petrosyan were used to galvanize feelings of national pride next to historical military leaders Tigran Mets, Vardan Mamikonyan and Davit Bek. The melancholy figure of composer–priest Komitas Vardapet, was particularly prominent in this new pantheon of secular Armenian mythology. As the emblematic martyr of the 1915 Genocide and a figurehead of the Armenian Enlightenment, he was ideally suited to be a metaphorical stand-in for the nation's collective spirit. Clad in a dark monastic tunic, Komitas's archetypal silhouette protruded out of the chekanka like a Christ-like vision invoking supernatural forces.

The mystical air of such images was also due, in part, to the material properties of the chekanka. Interloping the detailing of ecclesiastical artworks and the monumental shapes of medieval Armenian bas-reliefs, the embossed copper panels would shimmer in various metallic hues during daylight, infusing the interior with an aura of mystery and drama. The sacralizing intent is particularly evident in two horizontal panels representing Armenia's holiest sites – view of Khor-Virap overlooking Mount Ararat, and the Sevanavank monastery in Lake Sevan. Using a combination of copper and aluminum, these plaques rendered the omnipresent scenes into a new kind of a devotional object: a modern “antique” that coded the cultural landscape into a transparent allegory of Armenian selfhood. Predictably, these best-selling chekankas were especially popular with rural households as well as diasporan tourists, who started visiting the country in droves during the 1960s and 1970s.

In the relatively short span of its existence, the mass-produced Armenian chekanka underwent a rapid evolution that saw its transformation from a routine “folk” or decorative craft, to a veritable art form that was also an industrially-produced commodity. Though it was sternly critiqued in its time as indulgence in decorativism, and what the design historian Kiril Makarov has called “pseudonationalism,” the chekankas proved to be a complex and resilient cultural phenomenon.[6] By the 1980s, Yerevan's souvenir shops and salons featured much more elaborate alliterations of this wall art. While the more run-of-the mill product continued to dominate, a “colored” variation of the chekanka offered technically and conceptually much more refined options. Using a combination of embossing, molding and inlaying, these enameled examples of the chekanka were marketed as the “luxury” alternative for the discerning consumer. Though designed by professional members of the Artists Union of Armenia and hand-made by skilled artisans, these somewhat extravagant items could still be affordable for most middle-income households.

With their narrative-driven compositions, vividly-colored panels like “Armenia,” “Sardarapat” or “The Battle of Avarayr” could be mistaken for actual paintings, miniature frescoes, mosaics, vitrages or even cartoon strips. It was all a little too romantic, opulent and baroque – an apotheosis of the Soviet “ethno-camp” aesthetic. Though undeniably “kitsch,” the effect was never puerile – but not just a little camp. Indeed, the power of camp lies in the very serious manner with which it presents the overblown and ridiculously exaggerated, as manifested by all the great examples of this taste in visual culture: from the overtly sexualized Madonnas of Jean Fouquet to Superman comics and the films of Pedro Almodovar. Drawn by its ability to disrupt and confound, Susan Sontag famously argued that "Camp sees everything in quotation marks... [It] is a vision of the world in terms of style, but a particular style."[7] The strong affective power of camp meant that the administering of those quotation marks could imbue the chosen subject with potent political agency – a reason why so many contemporary artists still turn to it as both a source and a tool.

In the context of Brezhnev-era Soviet Armenia, the frivolousness of the chekankas explains why they were tolerated by the Communist leadership even when Sasuntsi Davit was posited for hero worship, or the Battle of Sardarapat was sold as the embodiment of Armenia’s liberation struggle. Seen more as “naive” expressions of provincial exoticism, the controversial neo-nationalist implications of the chekankas were generally dismissed by the state bodies that controlled the Soviet light industries. This allowed local designers and producers to instill the medium with political connotations that enabled feelings of cultural belonging outside of the repressive frameworks of the Communist State.

It should be admitted, though, that the spread and effectiveness of a popular art form like the chekanka, was also contingent upon the same ideological restrictions imposed by the Communist Party regime. In lieu of actual comic strips, erotica and advertising campaigns, the embossed figure of Sasuntsi Davits stood as the local equivalent of Batman, while the endless articulations of Aghtamar's voluptuous body did the job of resident ‘pin-up models.” It is not a coincidence that the chekanka instantly disappeared from the ranks of locally-produced commodities when Armenia gained independence in 1991 and rapidly adopted most forms of globalized consumer culture.

But what is most intriguing and fascinating about the chekankas from our perspective today, is the remarkably cohesive visual lingua-franca that they engendered. Hybridizing fine art and mass culture, popular tastes and modernist aesthetics, monumental and miniature forms, the decorative and the intellectual, the wall plaques generated an unconventional visual world in which ancient and modern mythologies, as well as sexual and political desires could be blended into a patently local – and unbroken – cultural narrative. Looking back at these ornate fixtures of the post-Stalinist, Soviet home decor, we must appreciate them not so much as charming talismans of a more innocent era, but as productive outcomes of a dialogue between the consumer market, industrial design and pressing cultural-political discourses of the time – an accord that is, sadly, entirely absent from the space of Armenian mass culture today.

---------------------

[1] The name comes from the Russian verb chekanit, which means “to mint” or “emboss.” The Armenian term for the technique – քանդակադրոշմ or դրվագած մետաղ – has never entered popular use.

[2] See Jean-Luc Nancy, “The Inoperative Community,” University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, London, 1991.

[3] This is also due to the fact that the chekanka was widely practiced by amateur or “naif” artists and provincial craftsmen long before the medium was given an industrial make-over.

[4] Clement Greenberg, 'Avant-Garde and Kitsch' (1939), in Art and Culture: Critical Essays, Beacon Press, Boston, 1989, p.9

[5] Paul Manning. “The Doe-Eyed Girl: The Face of Post-Stalinist Georgian Modernism,” in Semiotic Review, September 2019, https://www.semioticreview.com/ojs/index.php/sr/article/view/51/82 (accessed 10.04.2021).

[6] Kiril Makarov, Sovetskoe Dekorativnoe Iskusstvo [Soviet Decorative Art, in Russian], Sovetskiy Khudozhnik, Moscow, 1974, p.276.

from Et cetera

Notes From a Future Museum: Time-Keepers

By Vigen Galstyan

Vigen Galstyan explores the humble charm of Soviet Armenian mechanical clocks in this first instalment of a series of articles about Armenia’s not-too-distant past.

Listening to Imagine: A Post-Crisis Exhibition Attempting to Reimagine Armenia’s Future

By Liana Sahakyan

The ongoing crises in Armenia are forcing old ideas about the future to crumble, making way for as yet undefined horizons.

Escaping to Cafes: Yerevan’s 2021 Gastronomic Trends

By Ella Kanegarian

In the past several years, residents of Yerevan have started spending more time in cafes and the outdoors generally. We eat out, take our breaks, work and escape from the cares of our daily lives.

“Return the Tramway to Yerevan:” About Aram Pachyan’s Novel “P/F”

By Tigran Amiryan

Literary theorist Tigran Amiryan takes the reader on a journey into the essence of Aram Pachyan's experimental novel "P/F", noting that while it might not appeal to aficionados of fictional prose it will cause an unquenchable thirst for contemplation.

“Where Are You, Soghomon?” Arman Nshanian’s Melodrama About Komitas

By Sona Karapoghosyan

“Songs of Solomon” promises to tell the story of young Komitas but ends up disappointing as the direction drastically changes, turning into another tragic film about the Armenian Genocide.

Back to the Future: The Evolution of Post-Soviet Aesthetic in Armenian Fashion

By Anais Gyulbudaghyan

The Armenian love for following trends is something that is a part of the collective cultural and political history. And that tendency became stronger after the collapse of the Soviet Union.