Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

How can an Armenian reality[1] be circumscribed, if it can be circumscribed at all? First, we must consider the geographical location of the Armenian communities in question, then take into account the overwhelming majority of the host nation, their political, economic and cultural circumstances, examine the other settled minorities of the host nation, either indigeneous or migratory, and finally regard the size and influence of the Armenian community itself. Indeed, the reality of the Armenian community of the United States cannot be compared to the realities of those Armenians living in Europe, Turkey, Lebanon, Russia or Iran. Readers would certainly agree with these parameters; but would they accept if I were to maintain, without irony or malice, that the Armenians of the Republic of Armenia and of Artsakh also share a similar reality as those of the diasporan Armenians?

These many distinct realities of one civilization scattered throughout the world do indeed share one very prominent and inexorable reality: they represent a minority status. A minority that views itself, and even at times identifies itself, either through the eyes of the overwhelming majority of the host nation, be they Muslim, Christian, Jewish or Hindu,[2] or through the eyes of the other settled minorities, be they larger or smaller in proportion to theirs. This reality finds little or no real empathy with either the overwhelming majority or with the other ethnic minorities. There may be memorials erected in their name. There may be eloquent speeches and boisterous declarations on their behalf, affirming associations of friendship. And there may be copious literature and academic research of their history, explored and organized by the majority or to a lesser extent, by the ethnic communities in collaboration with the Armenian communities. But for all this “representation,” the Armenian communities remain a minority whose reality of this status has never really been comprehended for the simple reason that, to comprehend, one must consciously exercise ontic alterity with the individual or the community. If this exercise is not accomplished, a community's reality will remain separate, i.e. unshared ontologically.

I then raise the question: Why should the host nation, with its confirmed and overwhelming majority, besides for economic, political or academic profit, take an ontic interest in the Armenian reality? Why should the other settled minorities devote attention to such an exercise when, in fact, those minorities have oftentimes if not always positioned themselves as rivals to one another ever since their settlement as migrants or immigrants upon the soil of the host nation?

The reality of a minority status cannot be overlooked in respect to its dual relationship between the majority and the other minorities. On the world scale, Armenians represent one of the smallest civilizations: the Jewish population of Israel alone doubles that of all the Armenians in the world. The Kurds and the Palestinians, considered minorities in their respective territories, outnumber the Armenians by millions.

I am not stating that a nation's civilizing value lies in its numerical strength. The Armenians have proved the contrary: their numerical “weakness” or “deficiency” has forged a most extraordinary but, at the same time, a most tragic reality. The Armenian nation has offered humanity some of the most fabulous architectural and artistic gems known to mankind. Writers and poets have fashioned a language hardly changed since its birth. Armenian Christianity is unique inasmuch as its rituals lay deep in the spirit of Zoroaster and the Syriac Church.

This grandeur of the Armenian nation is certainly not the result of her “overwhelming majority.” She has not imposed her language or masonry prowess upon other colonized peoples. Nor has her grandness arisen through usurpation of another nation's artistic or aesthetic values, either by violence or by subterfuge. No, this grandeur springs from a nation whose existence has been continually hounded by clashing empires, belligerent neighbors, by the overwhelming majority of the host nation when tolerance of their minority status has reached intolerable limits, generally due to declining economies or martial circumstances. I would say that the Armenian reality is a vivid, almost translucid consciousness of the past that is ontologically inseparable from a daily, present-day existence; and that this lucid and intense consciousness of the past, inexorably bound to a present-day existence—wherever it be geographically—has been formed by and confined within a minority status to which the Armenians, because of their historical circumstances, have come to identify themselves, even those Armenians living within the legally bound borders of the Republic of Armenia. A reality founded over the centuries upon the apprehension and consternation of the arbitrary and contingency due to the inability to alter the reality of their demographic disadvantage.

Is there any solution to this aporia? Assimilation? History has shown that an assimilated people do not escape the wrath of the overwhelming majority when economic strife or war begins to take its toll; one only needs to consider the Armenians of Ottoman Turkey or the German Jews after World War I. Assimilation does not efface an ontological reality, and in fact experiments in forced assimilation have provoked contrary results.[3]

Be that as it may, instead of speculating on possible definitions of an undoubtedly indefinable historical reality, I shall rather attempt to explore, succinctly, the phenomenon of the Armenian separate reality as regards the geographical location of the community in question, its host nation, and more important still, as regards the other ethnic minorities of that host nation. Beginning with the communities settled on the periphery, I shall draw closer and closer to the epicenter, i.e., to the Republic of Armenia and Artsakh. For indeed if, historically speaking, the periphery has its distant origins in the epicenter, it is because all epicenters are problematic. The Armenian nation has its remote beginnings in today's Caucasian region; this is her epicenter. However, through invasion and war, this epicenter erupted and the centrifugal flow that ensued sent Armenians to the four corners of the Earth, the most westerly flow spreading over to the United States of America.[4]

Armenian Americans

The roughly one million Armenian Americans hold only one grievance toward their host nation: official Washington has not as yet acknowledged the Armenian Genocide. Has the U.S. not benefited economically, culturally and politically from the Armenian presence since their first wave of immigration during the Hamidian Massacres of 1894-1896? Why has Washington turned a deaf ear to Armenian claims for historical justice to date? Though U.S. officials will not deny that the genocide took place, their agreement with Turkey to silence any mention of it from the mouths of government representatives strikes at the existential core of Armenian Americans, for the genocide is ultimately the reason they live there

Yet, when we read that the Armenian lobby is one of the most influential in the U.S., and that many Armenians hold prestigious positions in American society, one cannot quite understand the adamance of Washington in not acknowledging what is an irrefutable historical fact, even ignoring motions by their own Congress and state legislatures. Not recognizing one of the greatest catastrophes of the twentieth century—a people and a culture totally annihilated from its place of birth—is a disavowal which discloses Washington's total indifference to the Armenian reality, and at the same time reveals the tragic cynicism of its geostrategic designs.

For strategic purposes, Washington shies away from offending Turkey's overweening pride: as a NATO member, possessing the second largest army of that alliance, special consideration has caused Washington to absolve or exculpate certain acts that Turkey has committed both against its neighbors and to her own citizens. Turkey's geographical importance has always been a well-known pretext to thwart any attempt of the Armenians to hold them to account. I imagine that Armenia bears little weight on the world scale against the military and economic potentialities of Turkey and Azerbaijan. Thus, even historic truths can be traded for profit. But there is another more disheartening reason.

The United States consists of a patchwork or juxtapositioning of a myriad of minority ethnic communities: Native American and Pacific Islander, African American, Hispanic/Latino, Jewish, Asian, Muslim, etc. Each community is represented by lobbies, vying for ascendancy, growth and advantages which preserve or enhance their respective interests, be they economic, political or cultural. These interests may not, however, be in the interest of another community; sometimes rivalries will form and communities will clash. Common causes are unfortunately rare among the minority communities of a host nation. Other minorities may consider Armenian Americans as a part of the White majority and project their grievances onto them, dismissing their struggles as secondary.

It would be difficult for a Native American to sympathize with an Armenian American. Although the two share many similarities of expropriation and extermination, it is understandable that, from the Native American’s perspective, the Armenian American is just another settler making use of land that was never theirs. Have Armenians shown solidarity with indigenous rights groups for them to stand side-by-side and demand genocide recognition?

There are the same parallels with the African American community. What would impel an African American to lend their voice to Armenians in their quest for recognition? Whatever their circumstances, Armenians came to the “land of the free” on their own accord, not in chains on slave ships. Armenians have never been bought and sold in the United States, or designated as another’s property. Although both groups have suffered greatly, it would be easier for the African American to leave Armenian issues to Armenians because they have “their own problems to worry about,” which continue to impact their daily lives.

And the large Jewish community? This is indeed a delicate issue: At first glance, the observer sees that both communities, albeit small in number, have contributed disproportionately to the betterment of mankind. Both communities, too, have endured humiliation, vindictiveness, pogroms and genocide. However, more recent efforts by Jewish American groups to advocate in favor of the Armenians can be overshadowed by past positions taken against congressional genocide recognition motions. That Israel has not acknowledged the genocide, and recently abetted Azerbaijan in the 2020 Artsakh War, might not be a consequence of the Jewish lobby in the United States. Nevertheless, it remains an obstacle to fighting against hate in solidarity.

It would thus appear that the Armenian American reality remains utterly isolated from both the ruling host majority and the other minorities, especially regarding the question of genocide. With this in mind, I shall now turn to the Armenian communities of Europe, particularly those of France.

European Armenians

The reality of the European Armenian may have corresponding existential traits with the Armenian communities of North America; for example, they are free to represent their culture through associations, films, literature, expositions, museums and monuments erected to the genocide. They are politically and economically active in their respective adopted countries. What does distinguish, though, the reality of the European Armenian and the Armenian American is that the genocide has been officially acknowledged by many European governments: Cyprus, Greece, Slovakia, France, Germany, Portugual, the Netherlands, Poland, etc.. To deny the genocide in Greece and in Slovakia is punishable by law. Officially at least, the host majority has exercised a fair share of empathy toward the Armenian communities across Europe. This being said, I am sorry to say that it is much more complex than that, and whether the European governments really exercise empathy is up for debate.

How is it that the governments of France and Germany have ignored the rise of Turkish associations on their soil without any investigation whatsoever into the intentions and the source of funds of these associations? There are about 700,000 Turks and 70,000 Azerbaijanis now residing in France, many of whom are affiliated with associations that are directly linked to Ankara, the most notorious of which are the bozkurt or the Grey Wolves. The Grey Wolves do not hide their hate for Armenians (or Jews or Kurds or Alevis). They are responsible for the desecration of Armenian cemeteries and memorials, vandalizing Armenian shops, the desecration of books, magazines or newspapers about Armenia in public libraries, violence against Armenians each year on April 24 during Genocide commemorations, and more recently during the 2020 Artsakh War.

These groups pledge, quite openly, complete allegiance to Ankara; that is, to Erdoğan's bellicose crusades. And it is these very Turkish associations in France and Germany that have engineered the vast propaganda machine set into motion from Ankara with its efficacy of Armenian hate, death threats and violence. A perfected propaganda machine that served the cause of Turks in Europe during the 2020 Artsakh War, a machine that the Armenians of France and Germany failed to counter strongly enough.

But it is not the task of the European Armenian communities to uproot and dismantle this machine or the associations that drive them; it is the host majority that must discern the difference between propaganda and cultural representation. It is the host majority that must ban the MIT (Milli İstihbarat Teşkilatı), the Turkish espionage agency, from French soil where it has been operating quite recklessly since Erdoğan took office, abducting Turks who are opposed to his government, financing the Grey Wolves or abetting them logistically during Armenian, Kurd or Alevite political or cultural demonstrations. And here we come to the crux of the problem.

Not only do European governments, and the majority of their citizens, totally ignore the Armenian reality, this ignorance was deployed in the most pretentious manner by politicians, journalists and pseudo-intellectuals who, during the 2020 Artsakh War, vociferated the most outrageous defamations toward and about the Armenians, the first and foremost being French President Emmanuel Macron himself.

Indeed, the war brought forth France's obsession with separatism. France had been plagued by Islamist attacks and troubled by issues concerning separate Muslim-oriented schools. This “separatist atmosphere” transpired in journalist's reporting of the war[5] and politicians’ interpretations of it, not only labelling but chastising the Armenians of Artsakh as “separatists,” and Nagorno-Karabakh as some break-away region torn from the territorial jurisdiction of Azerbaijan. It then became clear to most French citizens, who are completely ignorant of the whereabouts of Armenia and Artsakh, that Azerbaijan had the right to “win back” the territories that had been wrested from her in the First Karabakh War. The principles of French Republicanism do not condone any demonstration of “ethnic” autonomy or independence within a Republic, be it France's or Azerbaijan's. Mainstream mass media indefatigably repeated Armenia's “separatist” comportment, her militant attitude and obstinate resistance to admit it. These diatribes surely reinforced President Macron's own diatribes against Muslim “separatism” and Islamic “separatists” in France. Whether the president purposely collated the two events is difficult to say.

Worse still, Michel Onfray, a writer and intellectual, complicated matters more when he declared that the war was one between Christians and Muslims. That Onfray may parade his crass ignorance of Armenia's historical relationship to the Turks is unpardonable in light of the complex circumstances that wars provoke, and his injudicious and erroneous farrago might have been lost in the huge volume of all the other press reports;[6] alas, they were heard loud and clear, especially by the extreme Catholic right of France, whose many constituents soon saddled their horses and charged out with the crusader banner waving high, identifying thus the Armenian community of France with all the Oriental Christian victims of jihadist or Islamic torturers.[7]

To confuse a racial issue with a religious one truly acknowledges France's blindness regarding the Armenian reality. For not only did the wheels of the Turkish propaganda machine begin to grind out false information to counter the “victimization” of Armenians, the Armenians themselves, lost in a quagmire of falsehood, farrago and fabrication, constantly on the alert due to Turkish pressure and harassment, had no one to defend them, even the government.

It must be said in fairness, however, that the Armenian community reacted quickly to the aggressions and violence by the Grey Wolves, their claims and pleas were heard by the government, and the Grey Wolf movement has been officially outlawed, their associations and lobbies put under police surveillance. Their “youth training camps”[8] in the back regions of Ardèche have been dismantled. One cannot wholly blame the current French government's benightedness toward the Armenian reality, for government obsession with separatism is not completely ill-founded: 40% of the imams who give sermons on Fridays in France are of Turkish origin, and it has been estimated that 71 mosques are administered by pro-Caliphate Turkish groups. It is in fact these lobbies, associations, sermons and propaganda of Turkish origin in France that have, over the years, endeavored to dissuade the French senators in acknowledging the genocide and criminalizing its denial. How then should we interpret the resolution adopted by the French Senate on November 25, which recognized the independence of the Republic of Artsakh by 305 votes to 1?[9] Or the sudden disbanding of the Grey Wolves? Redemption of a guilty conscience? President Macron's “revenge” for Erdoğan's harangues against him? Perhaps.

Be that as it may, all this belated interest in the Armenians of Artsakh reflects the incompetence of over 20 years of negotiation by the OSCE Minsk Group, and especially the utter unconcernedness of the French government toward the suffering of the Armenians during the 44-day war. This tragic indifference also expresses the host government's pompously paraded participation in the humanitarian aid to the Armenians: a guilt gift to compensate their timorous and complacent policy toward Turkey and Azerbaijan?[10]

What all this does reflect is a host nation's ignorance of the Armenian reality, and this notwithstanding over a century of integration and assimilation of the Armenians in France. I suppose that the European governments are proud that they have officially recognized the genocide. Good. But perhaps now it is time to rid Europe of fascist Turkish groups that are bent on finishing a job that Turkey began and Azerbaijan seems keen on finishing. For what is the utility of the European nations to acknowledge a genocide and commemorate it on April 24 if there are hardly any Armenians left to gather together on that day?

The Turkish-Armenian: The “Local Foreigner”

The 60,000 or so Turkish citizens of Armenian origin, the majority of whom live in Istanbul, are subject to three miscomprehensions as to their very complex and ambivalent reality. Firstly, the overwhelming majority of the Sunni Turks have not only misjudged that reality but in fact firmly believe they possess no reality of their own, a sort of non-existent reality in view of the fact that they are citizens of the Turkish Republic, and being so, have only to rejoice at this Turkish reality. The Turkish host majority are firmly convinced that Armenians have happily assimilated and accommodated to one reality… theirs!

Secondly, a rather discouraging miscomprehension has its origins within the Armenian American communities, where many of them cannot accept that the Armenians of Turkey remain in the lands of their arch enemy, a land besotted with the blood of their ancestors. More incomprehensible to them still is that many Turkish-Armenians actually enjoy their lives in that land, and whose close friendships with Muslim Turks may outnumber those with other Armenians. This second miscomprehension is indeed due to the absence of any empathy toward Turkish-Armenians. And yet, we must ask the question: Why should an Armenian living in Turkey immigrate to the United States when, in fact, he or she is living on his or her land? The Armenian of Turkey has more historical rights to that land than the Muslim Turks themselves! Why then should they leave? If they did, who would bear witness to their history? Who would testify to the ontological bound of the Armenian to his or her soil? That is what I call an ontic reality; a reality that is not only ignored by Muslim Turks, but by many Armenians of the diaspora. There lies the ontological perplexity of the Turkish-Armenian… and perhaps his or her ontological tragedy. Let me cite Kristen Anais Bayrakdarian to support the complexity of this ambivalent reality:

“Many Armenians living outside of Turkey do not understand that so much of what is Armenian is Turkish and so much of what is Turkish is Armenian.”

This was exactly my position when I worked in Turkey during the 1980s.[12] Bayrakdarian interviews a certain Asiana who states quite emphatically:

“My Turkish and Armenian identities are not in conflict. In habits, customs, I represent both cultures. They're very similar… The two cultures embrace one another.”

How true this avowal is.[13]

The third miscomprehension is a question that the Armenians of Turkey and of the Republic of Armenia pose either to themselves or amongst themselves: Should the Armenian of Turkish citizenship renounce his or her nationality and immigrate to Armenia, dual-nationality being prohibited by the Turkish government? The answers that I culled were of two sorts: the majority of the Armenians of Istanbul are well-off and live quiet, agreeable lives. They have good jobs or do good business. Many own homes on the Princess Islands (on Kanal Adı in particular). Why should they immigrate to a country and begin anew? Furthermore, some even admitted to me that Armenia is “poor” (fakir) and would not even spend a holiday there![14] They complained, too, that the air flight is very costly, and since the border is closed between Turkey and Armenia, if one were to travel overland, it is necessary to pass through Georgia, and that expedition could take several days.

The other answer was quite straightforward: Turkey is the ancestral homeland of Armenians and to abandon this homeland would further empty the land of Armenians, exactly what the planners of the genocide hoped to achieve. As long as one Armenian soul remains in their original homeland, Armenia continues to exist, historically, and more importantly, ontologically.

And it is for this very ontological continuum that Turkish-Armenians must continue to live in Turkey, regardless of a reality that neither the Turkish Sunni majority nor the diasporan Armenians cannot understand.[15]

It goes without saying that centuries of coexistence and of cultural exchange, however superficial or one-sided it may appear, should not be condemened nor reproved. Turkey is the soil of their ancestors and Armenians of Turkish citizenship identify themselves with this soil, however the Muslim Turkish majority derides, denies or regards this identity as “sentimental nostalgia” or “haughty contempt.”[16]

As it stands, the reality of the Turkish-Armenian lies quite outside the preoccupation of the host majority, of the diasporan Armenians and to a lesser extent of the Armenians of the Republic. Indeed, this reality is problematic given the fact that their indigenous homeland has become estranged from them; they have become the “local foreigners.” Not subjects or citizens of a homeland, but of a conquering majority, be it Seljuk, Ottoman or Republican. This reality is not easy to assume, and one that exacerbates attempts to draw a sound and substantial identity from it. Since it is all but impossible to validate an existence as an Armenian before the host majority, besides shallow representations of their culture under the rigorous surveillance of that vigilant host, the “local foreigner” has little hope of sympathy, much less empathy. Nor do they expect much empathy from the diasporan Armenians. And the three million Armenians of the Republic?

Republic of Armenia and Artsakh: The Epicenter

Now I state quite emphatically that the Armenians of the Republic, albeit sovereign within their homeland, autonomous in their political, economic and cultural affairs, bear the stigmatized stamp of a minority status! I am not pretending to be haughty, contradictory or clever. It is a fact that, over the centuries, Armenia has been subjected to the most ruthless oppression by the vast and powerful empires that have always enclosed her. How could a population grow and thrive when it has been decimated? How many lynchings, massacres, pogroms, deportations and wars have reduced the Armenian population to what it is today? How many scattered to the four corners of the earth?

It goes without saying that Armenians do not constitute a minority in the Republic. Yet, their scant numbers are but a drop in the ocean of a Muslim Turkish population, Russian, Iranian, Kurdish, Azeri, etc. This demographic and geographic reality places the Armenians of the two Republics in a very delicate, almost intolerable position: Not only are they demographically inferior, since the 2020 Artsakh War, they have found themselves militarily and psychologically dependent on Russia. Now several Armenians in Yerevan confided in me that some of the two million or so Armenians who reside or have resided in Russia return to Armenia, either opening restaurants or investing in businesses, thus increasing the population and participating in its growth, whereas very few, if any, of the Armenians in Turkey ever return to Armenia. But this comparison is not equitable: Russian-Armenians were or are immigrants, albeit the children of those first waves of immigrants were born on Russian soil and do have Russian citizenship. Again, it must be emphasized that Turkish-Armenians are heirs of a long lineage on the very soil that once expounded their names, their institutions, their myriad places of worship. On the contrary, it is the overwhelming Turkish majority who were the migrants. Nevertheless, it is true that, if all the diasporan Armenians were to return to live and invest in the Republic, their numbers would certainly swell the population to about seven million! But this is mere speculation and dreaming; reality is somewhat harsher.[17]

Can three million Armenians confront and withstand the genocidal intentions of 75 million Turks and 11 million Azerbaijanis? Even with help from the diasporan Armenians, a population that has suffered such trials and tribulations in the past may indeed sustain a war, but for how long? Their numerical dearth would never bear the brunt of a long war or economic embargo. This is an unfortunate predicament, but not an aporia! It bears the sign of yet another obstacle to overcome, and a perilous one. All the more perilous and tragic that, on the scale of world civilizations, the Armenians are perched very high; they need not envy or covet the civilizations of other nations, including those that have beset them.

It is so difficult to come to grips with this evidence. Now certain historians argue that nations disappear through war, malady, genocide or assimilation. And this is true. However, many of the nations that have disappeared did not evolve into Statehood, had not constructed palaces, temples of worship, castles and fortresses, had not founded a religion whose linguistic means of expression imprinted both in hearts and on paper forms that would bear the Armenians over 17 centuries of persistent hardships, had not a long genealogy of royalty and aristocracy, a tradition of agricultural savoir-faire, craftsmanship and trade, and in our modern epoch, a solid bourgeoisie educated as diplomats, doctors, professors, lawyers and investors.

Despite these values, Armenians of the two Republics remain enclosed within a reality that has been imposed upon them from all quarters, and one that has been steadily integrated and assimilated by them: Turkish, Russian, Iranian realities that pervade and impregnate Armenia.[18] Undoubtedly, it is a question of realpolitik, of the balance of power, especially in the case with Russia. Are Russians to exercise empathy with Armenians because they are Christian? Because some of the finest generals in the Soviet Army were Armenians? Because the two million or so Armenians living in Russia hold prestigious posts and have integrated very easily into Russian society? In spite of all these assets, Armenians are regarded as just another minority community within the maze of all the ethnic communities of the vast Russian Federation. In fact, in Russia, Armenians are considered “black,” along with other Christian and Muslim minorities of the Caucasus.

What future then lies ahead for the Armenians of the two Republics? Manufacturing or purchasing high-tech military equipment to enhance defensive and offensive military persuasion, cybernetic espionage and assault, nuclear potency? I believe that these modern contrivances, if they were to become instruments of destruction, would eventually lead to self-destruction. There does, perhaps, lie one sound road ahead for the Armenians of the epicenter, and also for those of the periphery: It is the bond that binds them, ontologically, to their prodigious civilization, now disseminated over the Earth. I have only to quote Nietzsche to champion my point:

“He who has grown wise concerning old origins, behold, he will at last seek springs of the future and new origins.”[19]

This profound thought may ring of naivete to some. However, a “majority status” quasi-unattainable, what other solutions lie ahead besides the bold and relentless exploitation and production of a rich civilization; besides “acts” that lay the way toward an ontic presence, however small—for in no way does small imply insignificant—instead of mere “signs” that represent a forlorn culture. It is not a question of rejuvenating a culture; it is a question of unbroken, unintermitted constancy, constancy to one's ancestral legacy, and not necessarily to the soil of one's homeland, the sole bequest that is worthy of indefatigable individual and collective volition, which opens the heart to one's ontic Self and consequently to the Other.

by the same author

Turkish, Azerbaijani Identity Void and Genocide

By Paul Mirabile

Is it necessary to assimilate or exterminate a people to affirm one's identity? Has an Azerbaijani identity been founded upon the genocide of a people, who, like in Turkey, lived side by side with the Turkic populations until the rise of nationalism?

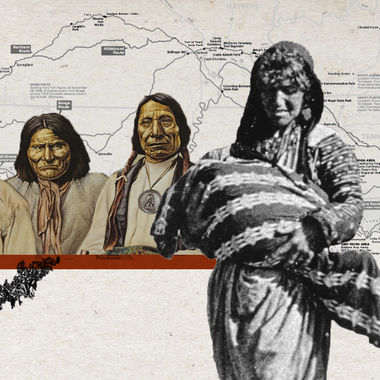

Convergences and Divergences in the Armenian and Native American Genocides

By Paul Mirabile

A nation that has been confronted by the choice to either adopt another's culture by subterfuge or by violence, or face cultural extinction is a nation that has experienced the agony of cultural genocide. A conversation between two historians.

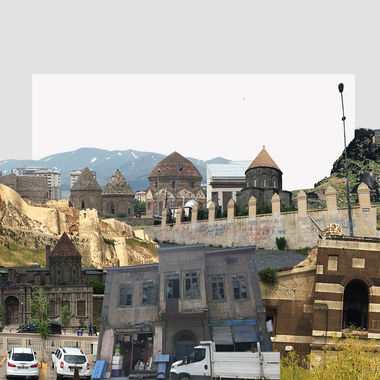

On the Frontier of Western and Eastern Armenia

By Paul Mirabile

Western Armenia or Eastern Turkey? This 'lost homeland' has been a thorn in Turkey's side since 1923. The thorn reminds the Turks and the Kurds of a people who lived and thrived in Turkey, and who played an enormous role in the unfolding of Turkey's history, writes Paul Mirabile.

Is the Study of the Middle Ages Possible in Turkey Today?

By Paul Mirabile

The essay attempts to offer several historical and pedagogical responses to the genocide of the Armenian people by suggesting a program on the study of the Middle Ages of Turkey, one that would entail the study of the three mediaeval epic tales that were forged during the Middle Ages on Anatolian soil.

also read

From a Fateful Revolution to the Dream of Pan-Turkism: Causes of the Armenian Genocide

By Suren Manukyan

Turkey continues to fight against the recognition of the Armenian Genocide through falsification of history, anti-Armenian propaganda, using all political, economic and lobbying levers at its disposal.

What is "Armenian" in Armenian Identity?

By Hratch Tchilingirian

In the last 100 years, there have been hierarchies of identity and canonical approaches to definitions of "Armenian," especially as articulated, rationalized and promoted by elites, institutions and political parties in the Diaspora and in Armenia. This essay is not a study of identity per se, but about one of the aspects of identity – the “Armenian” bit of it.

A Conceptual Gap: The Case of “Western Armenia”

By Varak Ketsemanian

“Western Armenia” as a concept is a crucial component of the Armenian national narrative, mostly in the Diaspora. In this article, Varak Ketsemanian raises some questions regarding the Armenian reality’s understanding of “Western Armenia,” its biases and blind-spots. He suggests refining the ways in which we discuss and represent “Western Armenia” in the 21st century.

The Intellectual Crisis of the Armenian Reality

By Varak Ketsemanian

Varak Ketsemanian presents a critical analysis of Sona B. Dadoyan’s work, “2015, The Armenian Condition in Hindsight and Foresight: A Discourse,” a timely and critical piece of scholarship that sheds light on the intellectual crisis of the 21st century Armenian reality.

Notre Heritage? The Uncomfortable Truths of Cultural Legacy in Peril

By Vigen Galstyan

The fire that severely damaged the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris highlighted how indispensable art is for humanity and exposed the fragility of all cultural legacy. It also indicated the profoundly unbalanced ways through which the global community has come to evaluate the intellectual production of different cultures and nations.

A New Generation of Istanbul Armenians

By Kristen Anais Bayrakdarian

This article explores the changing and evolving mindset of young Istanbul Armenians not only through a sociological lens but through a political one, exploring the history and changing political landscape of Turkey and the clear power distinction that exists between Armenians and Turks.

Redefining Home: Overcoming Feelings of Unbelonging in Children of the Diaspora

By Mariam Vahradyan

Suspended between two worlds, many Diasporan youth struggle with the question of belonging and the looming discomfort of never feeling able to maneuver through either culture.

Three Apples: The Relic

By Paul Chaderjian

After decades of moving from city to city, writer and journalist Paul Chaderjian ends up with a relic that has no place in his two suitcases of mere essentials. A personal story that comes full circle from orphanages in Aleppo to civil war Beirut to Fresno and New York to Doha and Istanbul.

How Genocide Survivors Made Yerevan Great

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

From those who survived the Armenian Genocide to those who moved to Soviet Armenia during the Great Repatriation of the 1940s, Western Armenians contributed to Yerevan’s incredible rise as a major city, turning it into the heart and soul of the Armenian nation.

Weaving a Safety Net: How Embroidering Links Two Waves of Armenian Refugees

By Varduhi Kirakosyan

For Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, and for Syrian-Armenians in Yerevan, crafting served as a way of earning a living and as a process of rebuilding and reimagining a social world through the temporal markers that help them nurture a sense of “home.”

The “New Woman” for the “New Nation”

By Hasmik Khalapyan

New national values and representations were being formed among Ottoman Armenians in the 19th century and the Woman's Question was an inseparable part of the formulation of a new national identity, Hasmik Khalapyan writes.

Armenian Women's Writing in the Ottoman Empire, Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries

By Hasmik Khalapyan

“A male writer is free to be average, but never a female writer.” This is what 19th century writer Srbouhi Dussap told Zabel Yesayan when she announced she wanted to be a writer. Hasmik Khalapyan traces the extraordinary lives of Armenian women writers of the Ottoman Empire.

Marriage Law and Culture: Ottoman Armenians and Women's Efforts for Reform

By Hasmik Khalapyan

Although Armenian women did not directly participate in the public discourse on the family structure and institution of marriage during the 19th to early 20th centuries in the Ottoman Empire, they articulated their concerns against gender inequalities through the voices of the fictional characters they created in their writings.

------------------------------------------------------

1- By “reality,” I am referring to an ontic reality and, to a lesser extent, an existential one. A community may represent its reality in the form of music, art, painting, literature, theatre, etc. But this “representation” does not necessarily disclose an ontic reality, which within its deepest strata preserves, in the case of Armenians, the wounds, afflictions and rankles of their ancestral legacy.

2- In Calcutta, there are about 150 Armenians. The majority were escapees from the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s. One family still lives in Chennai (Madras); they clean and repair the lone Armenian church when necessary. For an interesting insight into the history of Armenians in India, read Mesrovb Jacob Seth's Armenians in India: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day, (New Delhi, Asian Educational Studies, 1992).

3- In France, for example.

4- Canada, too, with approximately 100,000 Armenians, as well as South America. It is due to the efforts of those Armenians living in Uruguay that, in 1965, this country became the first in the world to officially acknowledge the genocide of the Armenians.

5- Let me make it clear that this reporting was heard and read in the mainstream media, not in independent media whose reports and articles explained as clearly as possible the complexity of the war.

6- There were about 700 articles on the war in the French press.

7- Certain information has been culled in France Arménie 'Quelques agneaux, beaucoup de loup', N° 483, March, 2021, pp. 2-29 and Nouvelles D'Arménie Magazine, 'Le Traitement médiatique du conflit passé en revue', N° 282, March 2021, pp. 62-65.

8- Military training camps for the young Turks enrolled in their ranks.

9- As could be expected, the pusillanimous President Macron did not accept the resolution. I suppose he felt that the humanitarian aid sent to Armenia would not chafe or displease either Azerbaijan or Turkey.

10- Turkey for commercial reasons, Azerbaijan for petrol. Unfortunately, Armenia does not weigh heavy enough on the Caucasian scale of realpolitik for France to invest seriously in her troubled existence.

11- I use the word “ambivalent” and not “ambiguous.” The relationship between an Armenian and a Turk in Turkey, in the eyes of an Armenian, is ambivalent. The ambivalence may appear “ambiguous” to the diasporan Armenian or any other outsider.

12- It has altered over the years, and more particularly during the later years of Erdoğan's reign. I do not disavow my book on the subject Dede Korkut and David of Sassoun : De Van à Roncevaux et au retour, Voies Itinérantes 1993, written in the 1980s in Turkey. However, the world has changed, Turkey has changed, and along with all these radical changes the Turkish-Armenian relationship, too… for the worse. Can this change also be due to all those radical global changes?

13- While discussing Turkish-Armenian relationships with a very good Armenian friend of mine during the 1980s in Istanbul, I stated rather hesitantly that Turks and Armenians seemed so culturally close. She smiled and agreed, but told me not to say it too loudly. It was this same friend, who on a visit to Armenian relatives in Washington, D.C., was reprimanded by them for asserting that the majority of her friends in Istanbul were of Turkish origin, and one or two her best friends!

14- On the other hand, many Armenians of Istanbul, too, go every year to Yerevan to see relatives or friends. They send their sons and daughters to the universities in the hope of them settling down there.

15- Relations between the Greek, Kurd and Jewish minorities of Turkey and Armenians have never given rise to any real joy, except to a certain extent and formally amongst the Christian communities during the ecumenical celebrations in the month of January. But to detail these complex relations would entail a big book.

16- The other minority ethnic groups of Turkey, including the Kurds, do not deny or deride this truism; their bearing toward Armenians has mostly been an unequivocal antagonism in the struggle for social survival amid a very aggressive host majority.

17- The majority of those who do immigrate are from Lebanon or Syria due to the long years of war and conflict.

18- Nevertheless, the Armenians living in Iran, approximately 80,000, because they do not suffer any political or economic pressure from the Shia Iranian host majority, do visit Armenia, invest and effectuate trade, all the more so since Armenia has banned over 2,000 products of Turkish origin since the end of the war. The Iranian-Armenian minority of Iran seems to be a rather privileged one in regards to the Azeri and Kurdish minorities. They have seats in Parliament as do the Armenians of Lebanon, who, too, suffer no discrimination as a minority. In fact, during the Lebanese civil war that tore ethnic minorities apart (1975-1990), the Armenian community came out miraculously unscathed, as if they had been forgotten during the melee.

19- Thus Spoke Zarathustra.