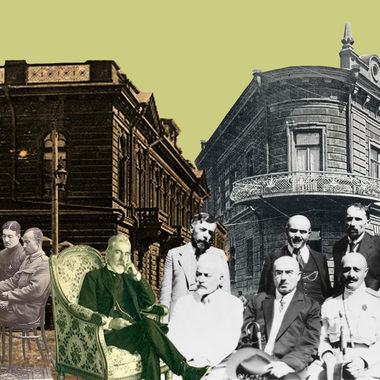

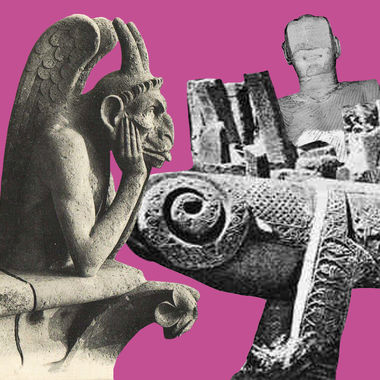

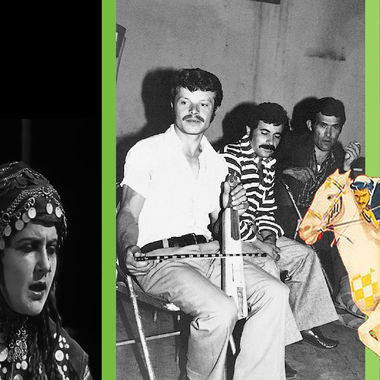

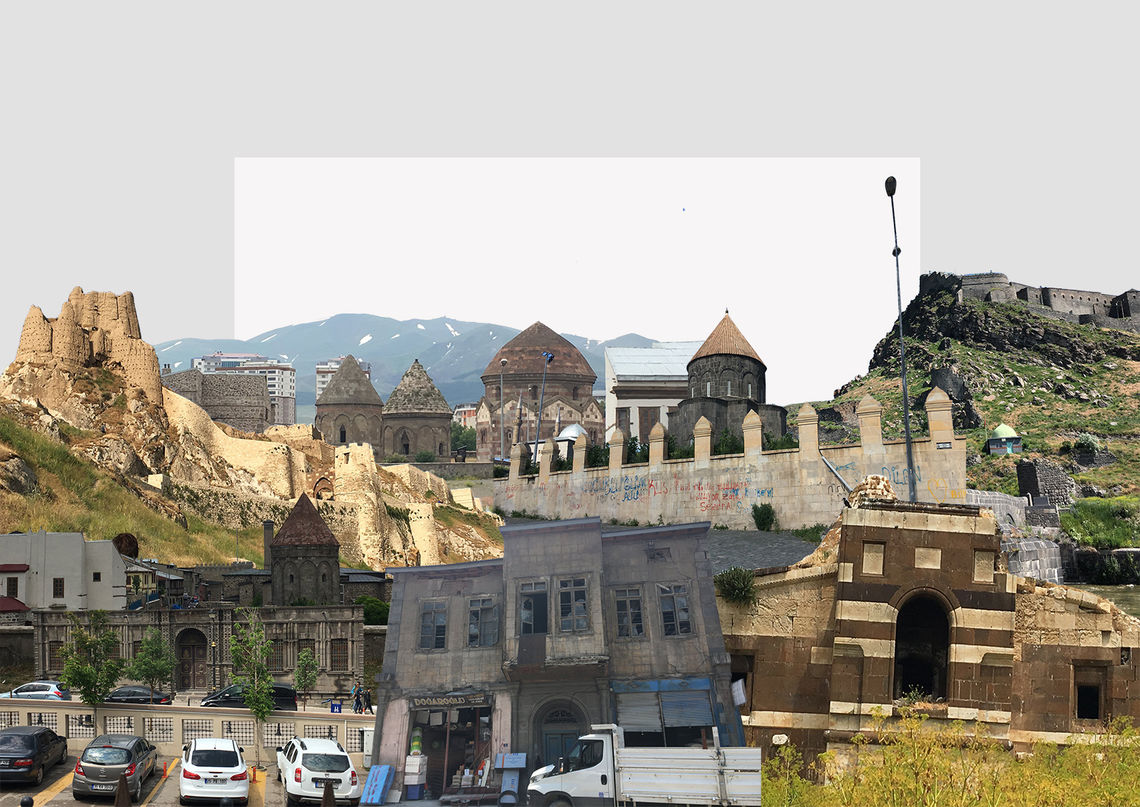

Images by Varak Ketsemanian.

Perhaps it is better to start with a disclaimer about a topic whose thoughtful discussion has evaded the Armenian reality for a long time, namely the episteme of “Western Armenia”/Eastern Turkey. This essay is not a political adjudication of who the rightful “owner” of “Western Armenia”/Eastern Turkey is or should be. Rather, it is an open invitation for a rational engagement with the changing realities of the 21st century and their impact on society in general and the Armenian political mind in particular.

More than providing exhaustive answers, this article is an attempt to raise some questions about an issue that the Armenian reality (in its diverse forms) has often grappled with but has only scratched its surface. Furthermore, it is an effort to detach or tone down emotions (national or patriotic) in an endeavor to understand further the residue of what remains of an “emotionless Western Armenia.” While this is not to suggest that a discussion about “Western Armenia” should or can necessarily be free of emotions, it is a proposition to address new questions and undertake new inquiries about the entity most Armenians call “Western Armenia.” Finally, it is important to state from the beginning that like many other national issues, “Western Armenia” is a “minefield” whose examination is not only politically charged but can quickly turn into a process of marking territories and serve as a projection board for one’s own assumptions and political investments.

Dispersed survivors of the Armenian Genocide bequeathed to the nascent Armenian communities a legacy of the “Old Country” (Yerkir), a notion that eventually came to be known as the lost homeland or what many Armenians would refer to as “Western Armenia.” While the first post-Genocide generation had a more concrete or palpable recollection of their ancestral homes from which they were deported, subsequent generations’ understanding of “Western Armenia” became amorphous with the passing of time. In other words, with the gradual disappearance of the survivor generation, the memory of “Western Armenia” started dissipating giving away to more abstract and ambiguous conceptions of the “old Armenian country.”

With the fiftieth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide in 1965 and the subsequent politicization of the Armenian diaspora in the 1970s and 1980s, the notion of the “lost homeland/territories” supplanted the previous “Old Country,” rendering the term “Western Armenia” (Arevmtahayasdan) a keyword in Armenian political discourse. However, while the discursive nature about “Western Armenia” mutated, changing from a bygone nostalgia to militant political demands and recognition, its content remained static and often formless. In other words, as the last traces of the pre-Genocide memory began fading away, the politicized Armenian diaspora continued latching on to the vestiges that their predecessors had transmitted to them, mostly because their conceptual supply had exhausted. As most (of these vestiges) consisted of stories and photos about former Armenian villages, churches, schools, monasteries, lakes and mountains, “Western Armenia” became the history of an imagined – though not artificial - territory whose conceptual demarcation changed from one person to another and was based on the family and the educational background that each had. In other words, while the politicization of the term pushed “Western Armenia” at the forefront of the Armenian political agenda (mostly in the diaspora), signaling the discursive turn that I mentioned above, its content remained in its previous form, namely the nostalgia of a lost homeland whose return to “its rightful owner” was now deemed imperative.

Armenian educational, political and cultural institutions and organizations reified this content of “Western Armenia” through consistent depictions of destroyed, ruined and abandoned churches, monasteries and old Armenian houses peppering a sprawling landscape. Consequently, most Armenians in the diaspora started (and still continue) [re]imagining “Western Armenia” not only as the lost but also the destitute homeland that awaits its rightful people. In other words, desolation and abandonment emerged as the marking features of the political discussion about “Western Armenia.” Thus, more than having a production of knowledge of the post-1915 situation as a process of critical and intellectual [self]-reflection, communal discussions easily spiraled into one-step attainment of comfortable self-certainty, namely a reiteration of the conventional national narrative. Pre-existing assumptions and strong emotional attachments to a once ancestral home, imagined yet unseen by most, became the primary outlet for any conversation or debate about “Western Armenia.”

The politicization of the term engendered two processes, namely, the “territorialization” and “dehumanization” of “Western Armenia.” On the one hand, territorialization in terms of [self]-identifying with a particular village, town, church or a monastery became fundamental for shaping new Armenian identities and rendering the continuum (from the lost homeland to the diaspora) the primary raison d’etre and the founding national narrative of the dispersed Armenian communities. The creation of local compatriotic associations (Hayrenaktsakan Miyoutioun) is just one of the many facets of this phenomenon. On the other hand, however, this perception of “Western Armenia” as a “lost territory” simultaneously lost its human factor or at least retained it in the same way that the first generation had done. In other words, the human element comes into the picture only when the discussion revolves around massacres, deportations and the Genocide. This created the impression and the perception of a ‘lost territory” which is bereft of any human element in its current form. Although many Armenians have started travelling to Eastern Turkey in recent years, only few succeeded in truly seeing and transmitting the human aspect of the region, while most confined their observations to the old material heritage now laying in ruins.

In this article, I argue that we need a thorough reconceptualization of “Western Armenia,” as a way of shifting the narrative from one of desolation and destitution to that of a lived human experience. I believe it is only through such a reassessment that we may be able to produce new knowledge and engage further with the episteme of “Western Armenia.” While the early generations in the diaspora had multiple reasons to territorialize and dehumanize “Western Armenia,” the realities as well as the facilities of the 21st century oblige us to bring the human element back into our discussions and the larger narrative. Although I am not proposing to forget or erase the conceptual baggage that our predecessors have bequeathed us, I am pushing for a need to address new questions including but not limited to: How do the current inhabitants of Eastern Turkey engage or interact with the former Armenian past of their villages and cities? Does shedding light on the modern lived culture of Kurds, Turks and Circassians in former Armenian villages and towns, change our understanding of “Western Armenia? What are the new conceptual tools that we need to develop to fully grasp the current realities of Eastern Turkey? And can we refine our comprehension of “Western Armenia” in a way that goes beyond ruins and abandoned churches?

I do not wish, of course, to be prescriptive, laying down a program others should follow and closing down other avenues of inquiry. Rather, my purpose is to ask a series of questions, which I believe can point towards new vectors of critical and constructive debates. Relying on some instances from a recent trip to Eastern Turkey, I will try to elucidate my points and explain further the need to refresh our conception of “Western Armenia.”

A refined conception of “Western Armenia” should first of all bring together the material and the human facets in order to shed a clearer light on the actual realities in a more holistic manner. We often forget that the abandoned material heritage that many Armenians identify with do not exist in a social vacuum. Although the ruins of the many churches and monasteries stand on remote hills and mountains, many others have become an integral part of the urban or rural landscapes of the emerging cities and towns. In other words, interweaving the two narratives of human and material experiences may help us understand better and explain the various ways in which the current inhabitants in Eastern Turkey relate, interact and engage with these transformed settings. The two narratives (material and human) operate through different logics. Destruction and annihilation form the content of the former (that Armenians as victims usually identify with), whereas emergence, creation, and proliferation characterize the human narrative (that the current inhabitants subscribe to).

The example of the Monastery of Varak may help to illustrate this point: The monastic complex, located on the outskirts of Van made significant cultural and educational contributions on the eve of the Genocide. Nowadays, only a small section is still standing, the rest remaining in ruins. While this short information is not new and is general knowledge by now, it is worth reiterating that such a characterization is a derivative of the material narrative, namely the propensity to describe solely in terms of desolation. While I am not arguing that things should not be named for what they are, an engagement with the current people surrounding the ruins of Varak may help us to look beyond and understand the complexity of these new settings.

I would not be the first person to state that what remains of the old monastic complex is now administered (or guarded) by a certain Muslim Kurdish man named Mehmet. He has “inherited” this task from his father and grandfather, who similarly looked after the last vestiges of the complex and had asked him to take good care of it, after they are gone. While it is easy to resort to cynicism to explain this phenomenon, namely Mehmet’s interest in making money from Armenian tourists often visiting this site - such an approach would not take it as far. It would be more constructive to start looking for answers that go beyond such simplistic interpretations or binaries. One cannot but ask himself, “Why did Mehmet’s family feel the need to look after the monastery? Or how does he relate to it when most houses in the vicinity have been constructed with the former bricks and stones of Varak? While the issue is not whether Mehmet is fully aware of Varak’s old Armenian heritage or not, but rather pertains to the construction of a new reality in relation to something that he may not readily (and religiously) identify with.

This reality is only a tiny instance of the intersection of the material and human narratives that I referred to above. It is a new episteme for our reality - a Muslim man looking after an old Armenian church. It is a new type of knowledge, unfamiliar to many, and knowledge that the current Armenian reality needs to grapple with and grasp through new conceptual tools. It is much easier to quantify the content of the material narrative than to provide a formula capable of explaining human interactions and relations to this materiality. How can we capture (or even quantify) this new reality then in a way to render it transmittable and intelligible to current and future generations when the material narrative - of ruins in vacuum - provides an important albeit only one side of the story? Do we need to rethink of the ways in which we represent the post-1915 Varak monastery in school textbooks, newspapers and the larger public discourse? Should Kurdish Mehmet even be part of the narrative about the Varak monastery? Not only does the integration of the human element into the overall picture push us to self-reflect on our discursive pedigree but provides a larger perspective into the current realities of modern Turkey.

Another example can be brought from Kars. Armenian tourists visiting the city believe that there is a particular location in the old district where the house of the famous Armenian poet Yeghishe Charents once stood, although no official documentation exists. The building remained standing until early 2019, when it was demolished. Now, tourists are only able to see its old site. The reason why I bring this up is not to use it as a projection board for reasserting how bad the Turkish authorities treat Armenian cultural heritage but rather as a window into the larger human interactions in relation to this place. In March 2019, local elections took place in Turkey. Analysts argued that the incumbent governor of Kars, a candidate in the elections, deliberately destroyed this house - which served as an important cultural site for many Armenian tourists - in order to mobilize the (ultra)nationalist electorate of the city and secure their votes.[1]

Whether this interpretation is accurate or not is not the decisive question here, but the fact that such buildings may be used for internal mobilization serves as another instance of how we can interweave the human and material narratives. While most Armenians would like to stress (rightfully) the demolition as the marking feature of this story, there is a human element that remains concealed in this representation. It is a small instance of how identities are shaped in Eastern Turkey vis-à-vis the material heritage that forms the bulk of the “Armenian narrative.” Furthermore, it shows how “abandoned sites” may come to the forefront of Turkish urban politics at any given moment. Therefore, as I argued in the first section, a reconceptualization of “Western Armenia” as both a human as well as a material narrative has the potential to better elucidate the social, political and cultural complexities of this geography. Furthermore, it pushes us to rethink and to reflect on our conceptual blind spots and shortcomings and the various ways in which those gaps could be filled. It is clear that “conventional” or “traditional” methods of representation and depictions have become obsolete and even misguided, rendering the construction of new models and explanatory paradigms imperative.

Perhaps the only instance when the human narrative comes closer to the material one in current Armenian discourse is the question and the recent fascination with Islamized/hidden Armenians. Although the full examination of this complex and politically loaded subject is beyond the scope of this article, I would like to use this issue to further reflect on the necessity of polishing our conceptual understandings and raise further questions for thought.

Unlike the monastery, the houses and the churches, the story of Islamized/hidden Armenians is or at least ought to be one about humans. Nevertheless, the preconceived notions and the conceptual baggage that current Armenians (in the diaspora as well as the Republic) carry, often hamper critical and constructive approaches. Notwithstanding the differences among the various groups, there is a tendency to look for an “authentic Armenianness” in the remote landscape of Eastern Turkey through observations that (often) carry normative undertones. The fact that we feel the need to put an identifier before “Armenian” speaks to this normativity. The recent excitement over the study of Islamized/hidden Armenians speaks to a process of “objectification” - if not outright “exoticization”- which can easily be inserted in the material narrative and its codex as another instance of an “abandoned” thing waiting to be [re]appropriated by the Armenian reality. While there is a tendency to believe that terms such as “Islamized” or “hidden” have explanatory powers, they conceal much more than they reveal. It censors the many facets of human interactions that have developed over the course of many decades, the transformations of the social and political structures of these families and their relationship with their surroundings including but not limited to the Turkish state. The question then usually becomes one of understanding the process through which they lost their former Armenian identity, rather than situating them within the larger Kurdish/Turkish society that they have been inhabiting for more than a century.

The dictation of the terms through which we speak, discuss, represent and talk about Islamized/hidden Armenians has occurred entirely independent of them; it is always “us” (the outsider) who speak for “them” (insider). Consequently, there is a process of reification whereby we reproduce the binaries that we wanted to avoid-us/them; islamized/conventional-no matter how hard we try to accommodate both groups under the homogeneous rubric of “Armenian”. This “rediscovery” engendered then new categories that resemble a discursive “straitjacket” woven by an outsider for its object of study, unfortunately reminiscent of the anthropological experiences of 19th century colonial observers. Once created, these categories, in turn, force a certain lens upon the visiting Armenian whereby the observation of certain Islamized Armenian families becomes a necessity and an integral part of the “authentic Western Armenian” experience or trip. Therefore, the term “Islamized” or other markers reveal much more about the intellectual pedigree and conceptual biases of the visiting or observing Armenian than about the “empirical realities” of these families -left behind in the “old homeland.”

The above mentioned examples are just a few instances of how the current Armenian conception of “Western Armenia” suffers from epistemic shortcomings and analytic blind spots. While this essay retold the already known story of the destruction of former Armenian churches, districts and monasteries, I tried to integrate the human narrative into the larger (mostly material) discourse about “Western Armenia” and its potential to elucidate the current complexities of modern Turkey. This reconceptualization is contingent upon other factors including new approaches to teaching Armenian and Turkish history, updated school textbooks, frequent visits and fresh empirical information. Finally, a critical engagement and reassessment of “Western Armenia” depends on its opening to a larger public discourse and scrutiny. In other words, a discussion of/about “Western Armenia” should not be the monopoly of certain cultural or political groups no matter how strongly attached they feel to it. Rather, “Western Armenia” in its current form is one of those avenues through which the Armenian political mind can/should go through in order to fill this conceptual gap and refine an important component of its national narrative.

------------------------------

[1] See: https://www.aravot.am/2019/03/02/1025272/?fbclid=IwAR1Cltix_FB3hST0zSbuoNBMfeWRyBObJHIxDPystb3TFxuPCGs8qdZlB4U

by the same author

Security Dilemma and Failed Opportunity: The Armenian Republic in Kars

By Varak Ketsemanian

In an exclusive interview with EVN Report’s contributor Varak Ketsemanian, Alexander Balistreri of the University of Basel reflects on some of the larger historical and historiographical problems pertinent to the region around Kars a century ago and sheds light on the political and military developments that shaped the policies of the Armenian government and the larger regional powers.

Records, Discourses and Memories: Narrating the First Republic

By Varak Ketsemanian

As Armenians prepare to mark the centennial of the First Armenian Republic (1918-1920), Varak Ketsemanian writes that there seems to be little consensus regarding its true meaning, its contested legacy and the various forms through which it should be commemorated.

Archives and Institutions of the First Republic

By Varak Ketsemanian

In this article, Varak Ketsemanian reflects on the possibilities of integrating the ARF archives on the First Republic into the larger political debate. Thus, he argues for the need of a critical and constructive re-assessment of this historical period in the nation's recent history, as a way to contribute to a long-term political convergence.

The Intellectual Crisis of the Armenian Reality

By Varak Ketsemanian

Varak Ketsemanian presents a critical analysis of Sona B. Dadoyan’s work, “2015, The Armenian Condition in Hindsight and Foresight: A Discourse,” a timely and critical piece of scholarship that sheds light on the intellectual crisis of the 21st century Armenian reality.

Armenia: Anatomy of a State

By Varak Ketsemanian

After more than 25 years of independence, what can the role of the Armenian Republic be in shaping a discourse that would speak of Armenia in terms of a “homeland” and a genuine state?

related

Is the Study of the Middle Ages Possible in Turkey Today?

By Paul Mirabile

The essay attempts to offer several historical and pedagogical responses to the genocide of the Armenian people by suggesting a program on the study of the Middle Ages of Turkey, one that would entail the study of the three mediaeval epic tales that were forged during the Middle Ages on Anatolian soil.

Notre Heritage? The Uncomfortable Truths of Cultural Legacy in Peril

By Vigen Galstyan

The fire that severely damaged the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris highlighted how indispensable art is for humanity and exposed the fragility of all cultural legacy. It also indicated the profoundly unbalanced ways through which the global community has come to evaluate the intellectual production of different cultures and nations.

The Kurdish Voice of Radio Yerevan

By Gayane Ghazaryan

Public Radio of Yerevan, known as Radyoya Erîvané or Erivan Radyosu* beyond the Armenian-Turkish border, has left a mark in the memories of thousands of Kurds across the Middle East, Europe and the former Soviet republics. Throughout the years when Kurdish language and culture were banned in Turkey, Radio Yerevan served as a bridge between the Kurdish people and their culture.

How Genocide Survivors Made Yerevan Great

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

From those who survived the Armenian Genocide to those who moved to Soviet Armenia during the Great Repatriation of the 1940s, Western Armenians contributed to Yerevan’s incredible rise as a major city, turning it into the heart and soul of the Armenian nation.