Fri May 25 2018 · 15 min read

Records, Discourses and Memories: Narrating the First Republic

By Varak Ketsemanian

The centennial of the First Armenian Republic is upon us. In a few days, Armenians will celebrate what came to be known as the reemergence of the lost Armenian statehood, the last vestiges of which were destroyed in 1375, with the Mamluk invasion of Cilicia and the subsequent collapse of the Rubenid Kingdom. Thus, the establishment of an Armenian Republic in 1918 that had a lingering memory in the political psyche of many Armenians will be commemorated in a national jubilee in Armenia proper and the Diaspora. Nevertheless, there seems to be little consensus regarding the true meaning of the First Republic, its contested legacy, and the various forms through which it should be commemorated.

In an excellent overview published last year, Ara Sanjian has demonstrated the impact of the Cold War in shaping the Armenians’ perception of the First Republic in the aftermath of its sovietization in 1920, and the subsequent development of two dialectically opposed accounts, one by the Soviet authorities and the other by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. As Sanjian points out, the history and the historiography of the First Republic became battlegrounds in which each one of these two factions tried to monopolize the discourse, created its own symbolism and thus molded the memory of the Republic in a way that fit with its own version of the national narrative.

Sanjian’s study sheds light on the major turning points throughout the Cold War, and the transformations through which the Soviet or ARF discourses on the First Republic went through until 1990. Drawing on some of the insights that Sanjian provides in his essay and continuing where he left off, this article analyzes some of the contemporary ways in which the First Republic is memorized. Shifting the emphasis to a Post-Soviet context, I argue that the political terminology and epistemology that undergirded the two dominant discourses throughout the Cold War still have a tremendous impact on the way Armenians talk or write about the First Republic.

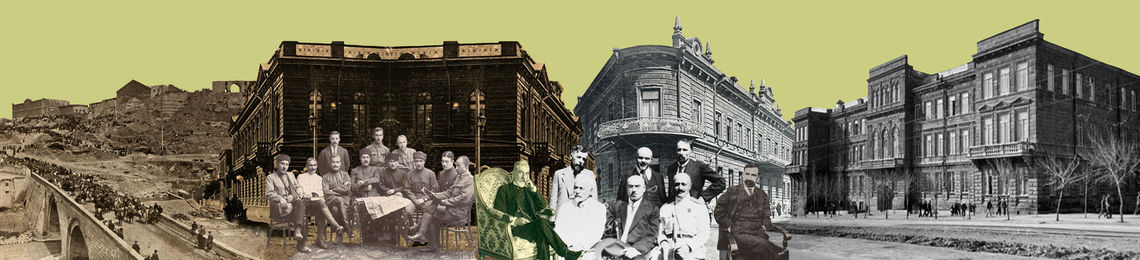

Aram Manukyan announcing the Armenian Republic; A painting by K.S. Shahbegian, 1965. (fig 1)

Gauging current public perceptions can be done through various ways. On the eve of the centennial, the number of debates, social media posts, and newspaper editorials are on the rise, providing us with ample material to have a clear idea of the larger picture. Using a wide array of material from social media, pictures, and printed articles, this work addresses four major themes, namely, the First Republic as a new political category, the problem of historiography, the role of education in the Diaspora, and the effects of these three on shaping public discourses about the Republic.

Shahbegian’s portrait of the First Republic (fig 1), a fascinating painting in itself helps us visualize some of the major questions that I will be tackling throughout this essay. It beautifully captures the four above mentioned themes, and thus constant reference to it will be made throughout the article.

The First Armenian Republic: A New Category?

What is the Armenian Republic? This question seems to invoke a rather easy answer, a historical problem to be more precise. Yet, it is much more complex than that. The establishment of an Armenian Republic introduced a new category in Armenian political thought, that of a Republic, a phenomenon that awaits its full appraisal in Armenia and more particularly in the Diaspora. Oftentimes, we represent the creation of the First Republic as the reemergence of the lost Armenian statehood, yet we rarely reflect on the intellectual corollaries of this potent term: State, L’Etat, Պետականութիւն. Are the state and the homeland the one and the same? Should they be so?

The term “Armenian Republic” itself, often taken for granted (epistemologically) necessitates further deliberations. Whereas the “Armenian” may capture the totality of “Western Armenia,” Cilicia, Javakhk and Artsakh, the “Republic” is a set of institutions and a mode of governance. The idea of a “state” may be inclusive of the “homeland,” yet it does not always work the other way around. I have tackled this issue in a different article and will not elaborate more here. Yet, it is important to reiterate that the state invokes a legal, and a political category that contains an objective truth, whereas the term “homeland” may invoke or appeal to different subjectivities, such as sensibilities of loss, or geographical imaginations that may stretch from Sasun to Shushi.

Symbolism, abstractions, and romanticism tend to overshadow the ontological reality that Armenia is an independent, internationally recognized, geographically demarcated, and a sovereign state with its political, legal, and social institutions. This then leads to political imaginaries among many Armenians that often regard the Armenian Republic as an “incomplete Armenia” implying thereby that there are still some “redeemable lands,” Thus, the primary question around which most debates revolve is “How did the Armenian State come to be?” without fully integrating the “What are the foundations that are necessary for the stability and the survival of this State?” This is particularly poignant in the Diaspora, as its sheer nature and the staunch anti-Soviet stance of the ARF throughout the Cold War have conditioned a considerable proportion of Diasporan Armenians to alienate themselves from what came to be known as the current Republic of Armenia.

When invoking the term “Armenian Republic” the emphasis is usually laid on the first, whereas questions such as “what it means to function as a state in the aftermath of centuries of imperial subjecthood?” remain unaddressed.

Different visions shaped by the social, cultural, economic, and historical trajectory of each community impacted the ways in which each constituent part of the Diaspora sees itself in relation to the other communities, and to Armenia.[1] Throughout most of the 20th century, whereas the ARF understood Soviet Armenia as an occupied and anti-national [ապազգային] unit, the Hunchakians and AGBU saw it as the best-case scenario. Deconstructing therefore the multiple understandings that various Diasporan communities have of “Armenia,” and peeling the multiple layers of meanings and values that have been attached to this notion remains a challenge for current Armenian political thought. As Gerard Libaridian argues, “the nationalism in the Diaspora was increasingly divorced from the social realities. Those who still carried the burden of the past tended to transform political concepts into abstract, moralistic values, and while the latter could provide a positive frame of identification for a threatened ethnic group, it could hardly bring any changes to the political future of a dispersed nation and its divided homeland.”[2]

After the fall of the Rubenid Dynasty in 1375, Armenians have become subjects of various empires, and it was only in 1918, with the establishment of the First Republic, that some kind of a national sovereignty emerged. This experience turned out to be short, as its existence came to an end in 1920. Thus, when invoking the term “Armenian Republic” [Hayastani Hanrapetutyun] the emphasis is usually laid on the first, whereas questions such as “what it means to function as a state in the aftermath of centuries of imperial subjecthood?” remain unaddressed.

History and Historiography

The depiction of the First Republic in 1918 as the reestablishment of Armenian statehood has led to the development of a particular historiographical paradigm that I call “Survivalism.” According to this historical interpretation and model, wars, massacres, and genocide are the most important markers of the Armenian political ethos. Ronald Suny presents this tendency as “often directed toward an ethnic rather than a broader international or scholarly audience, Armenian historical writing has been narrowly concerned with fostering a positive view of an endangered nationality. Popular writers, and journalists both in the diaspora and Armenia handed down a historical tradition replete with heroes, and villains, and scholars who might otherwise have enriched the national historiography withdrew from a field marked by unexamined nationalism and narcissism. Criticism has been avoided as it might aid ever-present enemies, and certain kinds of inquiry have been shunned as potential betrayals of the national cause.”[3]

The ossification of ethno-national boundaries in the early 20th century created a historical and historiographical logic whereby Armenians see their “centuries of suffering” and particularly the Genocide, as merely consequences of statelessness, explaining thus the establishment of the First Republic as the natural and the only conclusion of modern Armenian history. It thus becomes the pinnacle of the “national civilization” and particularly the end goal of the “Armenian Liberation Struggle.” Therefore, in a Post-Genocide setting the First Republic becomes an a priori end or purpose of Armenian History.

Armenian history textbooks have turned into timeless objects reflecting linearity with a strong emphasis on the “spirit” or the “soul” of the nation as the prime mover of its trajectory towards its predetermined end.

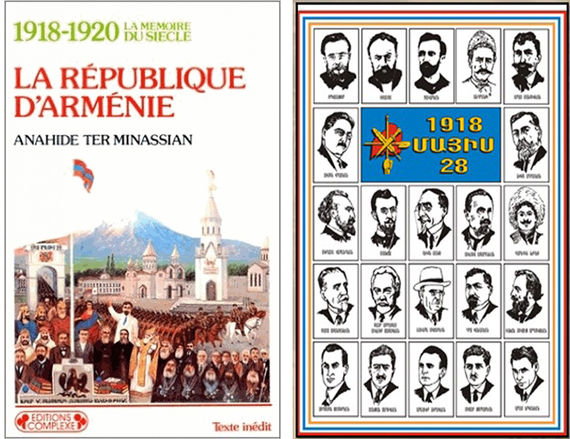

Shahbekian’s painting is the depiction of this trend par excellence. No wonder then we see it on the cover of Anahide Ter-Minassian’s La Republique D’Armenie. A closer look at Shahbegian’s work reveals this historiographical linearity. Not only does he portray the Armenian kings (on the left) and the officials of the Armenian Republic (on the left) as part and parcel of one historical continuum, the inclusion of some characters who never saw the Republic such as ARF founders Krisdapor Mikaelian, and Simon Zavarian, the Romantic Armenian writer of the 19th century Raffi (Hagop Melik Hagopian) and Khrimian Hayrik speaks to this teleological perception of the “Armenian Liberation Struggle.” It is not hard to guess that the painter has pro-ARF sympathies, as no “national leader” [ազգային գործիչ] affiliated with the Hunchakian or Ramgavar parties is shown. The work was painted in 1965, at the height of the Cold War when the latter two parties strongly identified with the Soviet authorities and formed a coalition bloc against the ARF. (fig 2)

Thus, to refer to Sanjian’s argument, the painting represents an attempt in monopolizing the memory of the First Republic through material depiction. The inclusion of Mt. Ararat, the clergymen, and the Apostolic Church in the background is yet another visual manifestation of the overemphasis on symbolism I referred to earlier. This then resulted in the selection of particular themes and accounts that would “fit” the grand national narrative, depending on where one stood on the political spectrum that defined the Armenian reality during the Cold War. This is how Sebouh Aslanian formulates this tendency: “Historical events and processes that have appeared to Armenian historians as going against the grain of their perception of the nation or the continuous self-manifestation of the Armenian “national essence” unfolding in the history have either been retrospectively displaced from the larger narrative or been downplayed and marginalized in favor of putatively national elements seen as more constitutive of Armenian national identity as it exists today. Such marginalized topics include gender and sexuality that might come across as “deviant” from the perspective of Armenian national historiography.” [4] (fig3)

Of course, it goes without saying that the above mentioned phenomenon of selective historiography found deep roots in the educational system of the Diaspora. Partisan affiliations and/or ideological commitments have often impacted the content of history textbooks that are used in Armenian schools. Thus, Armenian history textbooks have turned into timeless objects reflecting this linearity with a strong emphasis on the “spirit” or the “soul” of the nation as the prime mover of its trajectory towards its predetermined end. History classes in most ARF affiliated schools thus reinforce conventional narratives and paradigms, with particular focus on Party history, the Genocide, the First Republic, and the Artsakh Movement from 1988-1994 omitting thereby a 70-year period of Soviet-Armenian history and the post-1994 developments. History thus becomes a tool for identifying heroes or receiving communion rather than equipping students with the critical abilities to understand, and assess changes, ruptures, continuities and transformations.

(fig 2 & 3)

Public Discourses

Now that we have laid the groundwork and the historical antecedents for understanding and analyzing some of the contemporary public discourses regarding the First Republic, a few examples pertinent to the abovementioned problems will be given. Terminologies, jargons and words are strong tools that shape public discussions and perceptions of the First Republic. Without a proper engagement with the terms that we often use (consciously or otherwise) to describe, represent and retell the history of the First Republic, it would be hard to fully assess the legacy of the Cold War, and understand the larger argument of this article.

The deconstruction of political terminologies is a significant step in the overall question of the historical narrativization of the First Republic as they are strong instruments for privatizing or “alienating” national histories. Nowadays, public discourses surrounding the First Republic still portray the period between 1918-1920 as the “Dashnak Republic” [Դաշնակ Հանրապետութիւն] often ignoring the epistemological and ideological categories that underlie this term. Although the ARF was one of the most prominent political forces around which the history of the Republic revolved, political constructs such as the “Dashnak Republic” conceal how this label was perpetuated by the Soviet authorities as a way to discredit the Republic as “bourgeois nationalist” and the ARF as a “reactionary” force. Thus, it comes to no surprise that Turkish nationalist and mainstream historiography has adopted the same jargon [Taşnak Cumhuriyeti]. While “Dashnak” invokes a particular political stereotype (often reproduced through modern discourses), it is important to note that in the Armenian language, the term itself is senseless.

From an ARF perspective, the situation is not much better. Sympathizers of the ARF refuse to recognize Soviet Armenia as the “Second Republic,” castigating it as foreign occupation. Therefore, instead of the now conventional way of depicting the period 1918-1920 as the first, 1920-1991 as the second, and the post-1991 as the third republics, ARF officials and affiliates make the giant leap from First to Third (marked as Second) without recognizing the strong impact of the second (Soviet). This is another manifestation of the problem I discussed in the first section, namely the difficulty of grappling with a new political category, that of a Republican state. If we were to explore the institutions that governed and sustained the first, second and third republics as republics per se, the fact that there exist major continuities (as well as breaks) among the three becomes indubitable. Therefore, more than debating whether Sovietization is tantamount to foreign occupation, it behooves us to discuss the institutional changes, transformations and parallels among the three republics. It is through such an appraisal that we would be able to evaluate the impact of new epistemological categories on modern Armenian political thought.

(fig 4)

The February 18 uprising of 1921 against the Bolshevik authorities and its repression by the Red Army in Armenia is one of the most contested episodes in the early history of Soviet Armenia. Whereas Soviet-Armenian historians tried to describe this revolt as a “bourgeois-nationalist” reaction against Bolshevik socialism, ARF sympathizers still commemorate it as the party’s last heroic attempt to “save” Armenia from foreign or even “tyrannical” rule. A quick glance at ARF affiliated newspapers in the Diaspora will give us a sense of this phenomenon. While rarely does the Armenian media (in the Republic) remember the February events, ARF circles in the Diaspora perpetuate a manichean discourse through which the “good” and the “evil” are clearly discerned. The editorial and articles titles below are just a few examples of this trend. [The February Uprising Became a Barrier Against Dictatorship (1)], [The Last Heroism of the Fedayis (2)], [February 18: A Tragic End to a Promising Beginning (3), [The Majesticity of the February 18 Uprising (4)]. (fig 4)

(fig 5)

(fig 6)

The Cold War has provided the anti-ARF camp with a few “classics” that are often used to criticize the ARF (whether in the Diaspora or Armenia proper) and tarnish its reputation. Hovhannes Katchaznuni’s “The ARF Has Nothing to do Anymore” [Դաշնակցութիւնը այլեւս անելիք Չունի] is the most well-known and common. Written by one of the former prime ministers of the First Republic, and an ex-member of the ARF, his book with its “excellent” title (a ready weapon from an anti-ARF perspective) is often decontextualized to address contemporary problems and launch polemics against the ARF. An article published in Armenia during the “Sasna Dzrer” turmoil in the summer of 2016 and titled “Really! The ARF has nothing to do anymore” an obvious play on words of Katchaznuni’s work, is yet another manifestation of this trend (fig 5)

The second example is K. Serop Papazian’s Patriotism Perverted, a strong opprobrium against the ARF published in 1934. Although the book was produced against the background of the assassination of Leon Tourian in New York in 1933, an event that deeply divided the Armenian-American community (the scars of which are still felt today), its strong anti-ARF polemic has rendered it into one of the tools upon which anti-ARF discourses rely. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the book has found its way into anti-Armenian Turkish online forums and websites. The phraseology of Papazian’s narrative is often reproduced in contemporary debates with little alterations. An excerpt would be elucidating: “The task of presenting the Dashnagtzoutune [ARF] in its true political and moral character was rather difficult, as this society has had the agility of repeatedly changing its face and color with perfect ease of conscience. At first, they were nationalists diluted with socialism; then they turned out and out socialists, with Bolshevistic leanings, and adopted the red flag for their emblem. However, it co -operated with the imperialistic tyrants of Turkey.”[5] The expression “Bolshevistic leanings” is bolded to show the parallels with Narine Tukhikyan’s recent statement regarding ARF officials in Armenia. In a response to the former Minister of Education and ARF member Levon Mkrtchyan’s calls for giving Russian a special status in the Armenian educational system, Tukhikyan, the director of the Tumanyan Museum claimed that Mkrtchian and the ARF leadership of Armenia are Neo-Komsomols. Although uttered in a totally different context, Tukhikyan’s words are reminiscent of Papazian’s polemic. (fig 6)

(fig 7)

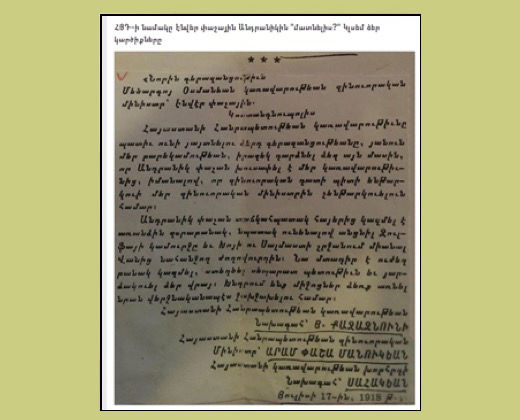

Throughout much of the 20th century, in their ideological and actual struggle against the ARF organization in the Diaspora, the Soviet authorities engaged in an active process of fabricating documents that were used to taint the ARF’s reputation among the Armenians. One of these “notoriously famous” documents has re-emerged on social media recently. It is a letter sent to the Ottoman War Minister Enver Pasha in 1918, and supposedly signed by Aram Manukian and Hovhannes Katchaznuni, asking the former to collaborate in order to “get rid of” Andranik Pasha (Ozanian), the pioneer of the Armenian revolutionary movement in Armenian public perception. (fig 7). Despite the fact that the director of the Armenian National Archives, Amadouni Virapyan has demonstrated that the memo in question is a forged Soviet paper, its constant reappearance through social media posts and the polemical debates that ensue is another testament to the Cold War legacy.

When it comes to the symbolism of the First Republic, one of the most contested issues that spurred a heated public debate was the question of Aram Manukian’s status. Upon the Armenian authorities’ decision in 2017 to erect a statue in memory of Aram and inaugurate it on the eve of the centennial, few voices emerged in Armenia that disagreed with the entire enterprise. Some of these men claimed that although Aram was an important figure in the history of the Republic, he should or cannot be regarded as a national symbol meriting a statue. A strong barrage of criticisms by ARF circles from Armenia and abroad followed such announcements, as many beseeched the Armenian authorities to not only erect a monument for Aram’s memory, but also build it on the Republic Square, in the exact same location where Lenin’s former statue stood. For ARF affiliates, this was yet another move for de-sovietizing the history of the current Republic and downgrading the Bolshevik legacy. Some even went further arguing that those who opposed this initiative were the “pioneers of denationalization,” an expression falling little short of “national treason.”

The contestation over national symbols continued yet in another domain, namely the new Dram currency that the Armenian government decided to issue on the eve of the centennial of the Republic. Not one single figure from the history of the Republic was/is depicted on the new Dram, which sparked a wave of criticism that many ARF sympathizers and otherwise rightfully voiced. The selection of a few characters such as William Saroyan and Hovhannes Aivazovsky irritated many ARF affiliates to an extent where statements were made claiming that the Central Bank of Armenia was unaware that 2018 was the centennial of the Republic, as is shown in the picture (fig 8).

Conclusion

(fig 8)

The above mentioned examples were all instances in which Armenians engaged in an active effort of “salvaging” the memory of the First Republic and the ARF reputation, or marginalizing the latter, if not tarnishing it all. More than making normative judgements regarding who should constitute a national symbol, or whether the statements made by “both camps” were true or false, this article argued that the legacy of the Cold War and the epistemological toolkit that it provided the Armenian reality with, still plays an instrumental role in shaping public discourses regarding the First Republic. On the eve of the centennial, debates, arguments, and postings that are reminiscent of the Cold War era when two ideologically and political demarcated factions vied for control over the Armenian communities, are again on the rise. In an environment in which Armenian society remains strictly divided along party lines, it is incumbent upon the current government to foster a public discourse that renders the national jubilee and its symbolism as inclusive as possible.