Sun Mar 08 2020 · 11 min read

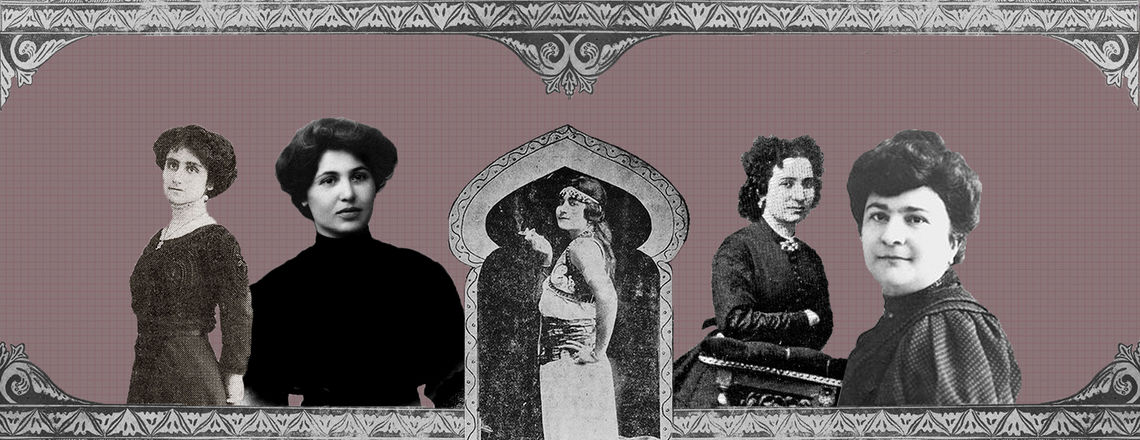

The “New Woman” for the “New Nation”

The Woman’s Question and Feminism Defined Among Ottoman Armenians

By Hasmik Khalapyan

Introduction

Over the course of the 19th century, several political events greatly impacted the way Armenian reformers in the Ottoman Empire[1] came to “imagine” the Armenian nation and how to modernize its institutions. Among these events was the Russian occupation of Eastern Armenia in 1828, following the Russo-Persian War, the Tanzimat Reforms in the Ottoman Empire (1839-1876), the French Revolution of 1848, and the adoption of the Armenian Constitution in 1863. The rising group of urban Armenian reformers, in response to new economic developments and social change, strived to create a distinctive “Armenian” space with middle class cultural ideals and beliefs.

A set of new "universal" terms, such as liberty, equality, etc, became popularized and used in the new definitions of national identity. These developments motivated discussions and arguments about the nature and role of women as well. Through a review of some of the major arguments of the time, this article illustrates how women were integrated into nationalist projects both as icons of modernity and bearers of Armenian traditional culture, an ambiguity that as Nukhet Sirman has pointed out, “feminists have had to grapple with ever since.”[2]

The Woman's Question Defined

The Woman’s Question was discussed and debated within the general context of a cultural awakening and national progress that a handful of educated Armenians envisioned for the Armenian community in the Ottoman Empire. The language of humanism, egalitarianism and progress was employed to advocate change in the gender structure of society through the prescription of new roles to women: “As a human being, a woman has the right to strive for a status [in society] corresponding to her abilities. The human society, for the sake of its own balance, must recognize this just right of its beautiful half.”[3]

National progress, civilization and women's status were rendered interwoven. According to Grigor Otian: “History shows a tight link between the issue of women’s emancipation and a nation’s civilization. It is the odds and ends of old barbarity [preserved] in contemporary societies that fetters a woman’s destiny. Laws must be changed. A woman has to have balanced rights. The rights of one [sex] should not be depravation for the other [sex]. The conditions of activity of one [sex] should be adapted to the gifts each sex has been given by Nature.”[4]

The “agenda” that reformer men put forward for women’s elevation in society, defined women’s role in relation to family and nation with particular historical claims to traditions on the one hand, and openness to the demands of time on the other. Women were seen as the mothers of the nation and in this role, they had to be educated and integrated into the overall campaign for the moral and physical well being of the nation. Education was the means by which “good” national mothers were to be produced to bring up future generations because “[a] child’s education must begin from the lullaby. But how can one do this without educated mothers?”[5]

What started out as an urgency to have mother-educators developed into a discussion of modernizing women for new roles in society. The number of educated women was on the rise, a fact that justified women's entry into the public sphere. Two women’s educational organizations established in 1879, the Patriotic Armenian Women’s Association (Azganver Hayouhats Enkeroutioun) and School-Loving Ladies’ Association (Dprotsasirats Tiknants Mioutioun), played a major role in the history of education, and women became publicly visible in unprecedented ways, transforming into objects of pride and encouragement for male reformers.

Achieving the Middle Class Ideal

Family, under the nationalist discourse, acquired a new significance and women’s role in it was ever more important. The fate of the nation came to be regarded as dependent on the self-devotion of women to their families, understood as the constitutive unit of the nation.[6] Thus, the prescription of new roles at home was inspired by a new middle class ideal of womanhood, which was seen to be achieved through uplifting lower and middle class women, and a simplification of the lifestyles of women of the upper classes. Women were singled out as irreplaceable in their roles in the family: “The fatherly feeling in itself is not sufficient to warm the familial nest. It is the wife who spreads around the delightful warmth. It is the motherly feeling that makes a home a home, educates the toddler, gives light to the cottage and the palace… The father… is only a natural need, while the mother is the heart [of the home] from the very first second she becomes a mother.”[7]

Since middle class women looked up to the upper classes and copied their lifestyles, upper class women were asked to be conscious of their behavior to serve as models for less privileged women: “It is the reality that modern mothers do not love their children as much as mothers in older times. In earlier times, mothers used to dress their young children themselves, cared about their children’s looks and only afterwards took care of themselves. But who cares about the children in our times? Every woman cares only about her own looks nowadays. A maid or a servant, with her dirty hands, dresses the children while the housewife examines herself from all angles in the mirror…”[8]

As “architects of the institution of language,” women were regarded to be responsible for the correct usage of language by their children, therefore handing them to the care of others was condemned.[9] Keeping wet-nurses was likewise criticized and believed to be a “bitter fashion” imitated from Europe.[10] Efforts were made by reformers to transform and elevate domesticity into a modern profession suitable for the modern woman and attractive to middle and upper class women. Motherhood and wifehood were referred to as scientific occupations and further encouraged through publication of information on family and children’s health issues in which women’s role was emphasized as pivotal.[11] The ideal New Woman in the private sphere had to be multi-skilled and multitasking to appear as “both the servant, and the queen of the home.” She was to direct her efforts to the improvement of “our mores, educate our children and become models of gracefulness and decency.”[12]

The middle and upper class women were called upon to simplify their "over-Europeanized" and luxurious lifestyles to correspond to the new middle class ideal as envisioned by the reformers. “Love for simplicity” (parzasiroutioun) was the slogan of the day preached by the press[13] and even the Patriarchs themselves.[14] The simplicity-loving, non-idle woman and mother was the ideal New Woman in the private sphere. When extended from home to the public sphere, the idea behind the call for parzasiroutioun for upper-class women was that it was inappropriate for women to continue to lead luxurious lifestyles when a predominant part of the Armenian community was in economic misery. Leisurely lifestyles were no longer tolerated and the reformers demanded that women, who could afford any spare time outside the household and away from (paid) work, take up active roles in public.

For middle-class women, the new public sphere was two-fold. On the one hand, it signaled their entry into paid labor. On the other hand, as the group of educated women who stood closer to the “crowds” than the upper classes, they were asked to directly participate in the modernization of women of their own class and classes below them through educating them for the new roles.[15]

For the urban lower classes, the new public sphere was mandated education, often vocational, which guaranteed their entry into paid household or factory labor.[16] For the provincial lower classes, a partial shift occurred from agrarian labor to industrial household or factory labor. Often they were called the true feminists because their public visibility had occurred much earlier.[17]

Modern-Yet-Modest

Certainly, most women were happy about the call for active roles in the nation as it gave them the public visibility otherwise denied to them. As new perceptions of the private and public spheres and definitions of the New Armenian Woman were being formulated, the actual changes taking place did not always correspond to the image of the woman that the reformers had imagined. As I have argued elsewhere, the New Woman did not emerge as a stable entity as the reformers had hoped. She was emblematic of the transformations and ambiguities common to the reformers’ own search for Armenian modernity. Through negotiations and debates on the meanings of the New Woman and feminism, the reformers sought to bring an accord between the real (new) woman and the woman in their imaginations. As Zubaida has pointed out in the Islamic cases, the principle enemy of reformers was “backwardness” rather than foreignness.[18] Yet, there was to be moderation between the Old and the New. The Armenian woman had to be like “an Armenian mother but certainly reformed in accordance with the dictates of the time.”[19]

How was the issue of discrepancy between reality and discourse, actuality and imagination to be solved? The remarkable (or not so) aspect in the assessment of women’s new identity is that it was achieved only through comparison and in relation to Europe. This ideal New Woman borrowed the understanding of new womanhood from Europe, but she did so selectively: “[A]lthough of high social status, greatly educated and in possession of selective gifts of European Enlightenment, as true Armenian Women, [they] are exemplary models of Armenian simplicity, humbleness and decency... Whenever selective education and enlightenment are combined with indigenous national features, the Armenian woman comes out of it as super-noble and acts out of her moral consciousness.”[20]

Whether or not feminism was a positive movement, and whether or not being a feminist was acceptable largely depended on which particular aspect of the issue was under discussion. Seen from the angle of progress and civilization, feminism as a movement appeared attractive to the reformers, who sought intellectual and philosophical resemblance with Europe. Many newspapers referred to the international women’s movements both in an effort to familiarize readers with the feminist movement, and to illustrate in which ways European women’s movements could serve as an example for Armenian women. Feminism, if developed “in the right way,” could in an ideal movement take up the aspects of social life that had been unattended by men.[21]

Yet, feminism could have a positive impact on the Armenian nation only if women made “selections” with special care. A general belief was that overexcitement with everything new not only destroyed local traditions, but “the remains of the old and the traces of the new make a disgusting mixture.”[22]

The Armenian woman, on a general level, was rendered as not yet mature to make the right choice. European civilization and feminism, in case of “ignorance,” could have a disastrous impact on women. Grigor Zohrab feared the impact of Serbouhi Dussap’s feminist novel Mayta on the readership: “We are fearful that unexpected and too strong a light may damage the long-used-to-darkness eyes of our nation, which has only started stepping into the rays of enlightenment. We are especially fearful that what is taken for a vital light may turn out to be merely a misleading sparkle.”[23]

Presenting women as ignorant and incapable of making right choices was the means through which the reformers expressed their frustration over the visible changes in women’s appearance, behavior and gender norms often beyond their control, making reformers believe that “women are getting the crown of society into their hands.”[24] The title “feminist” carried a negative meaning and could at times signify a fallen woman. Feminism and feminists were ridiculed through grotesque emphasis on some features of the movement.[25]

The term was considered as existing in an uncomfortable alliance with motherhood. Thus, when Serbouhi Dussap quit her public activism after the death of her daughter, prominent intellectual Arshak Alboyajian, otherwise calling Dussap “a feminist” and “an advocate for women’s cause,” triumphantly declared that “she proved with her example that a woman is a ‘mother’ before and above everything else.”[26] The journal Massis, on the other hand, found it important to defend Dussap against being termed “feminist” by Alboyajian by claiming that Dussap only propagated its readers “to choose true love.” Her theory “is in no way related to contemporary European feminists’ demands for radical changes in women’s situation.”[27]

The reformers were squeezed between the desire to be progressive (understood as European), and the attempts to hamper European influences that took away women’s modesty, which was considered to be “the most important feature of Armenian women.”[28] As Yuval Davis has pointed out, women are the bearers of “the burden of representation of the collectivity’s identity and future destiny” and responsible for the “collectivity’s honor.”[29] To preserve the nation’s honor, the ideal New Woman was expected to emerge out of these paradoxes and ambiguities “modern-yet-modest.”[30]

Conclusion

In the course of the 19th century, new national values and representations were being formed among Ottoman Armenians under European economic and cultural influence and Ottoman imperial domination. The Woman's Question was an inseparable part of the formulations of the new national identity. Upper- and middle-class women were invited to have their contribution in the creation of a national identity and culture and help raise the status of their less fortunate urban and provincial sisters. Under the complex interaction with European and local understandings of modernity, the Armenian Woman had to represent multiple temporal, spatial and hierarchical identities.

also read

Marriage Law and Culture: Ottoman Armenians and Women's Efforts for Reform

By Hasmik Khalapyan

Although Armenian women did not directly participate in the public discourse on the family structure and institution of marriage during the 19th to early 20th centuries in the Ottoman Empire, they articulated their concerns against gender inequalities through the voices of the fictional characters they created in their writings.

Armenian Women's Writing in the Ottoman Empire, Late 19th to Early 20th Centuries

By Hasmik Khalapyan

“A male writer is free to be average, but never a female writer.” This is what 19th century writer Srbouhi Dussap told Zabel Yesayan when she announced she wanted to be a writer. Hasmik Khalapyan traces the extraordinary lives of Armenian women writers of the Ottoman Empire.

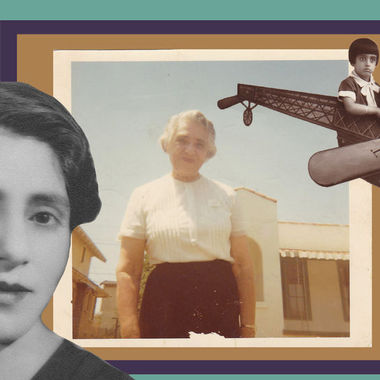

From The Forgotten Pages of History

From the Forgotten Pages of History: The Life and Times of Mari Beylerian

By Arpine Haroyan

Western Armenian writer and editor Mari Beylerian perished during the 1915 Armenian Genocide. While there is scarce information about her life, she left behind the legacy of Ardemis, a monthly magazine published in Egypt and devoted to women’s rights.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: Ellen Buzand’s Journey From the Battle of Sardarapat to a Cheka Prison

By Arpine Haroyan

A writer, resistance fighter, political prisoner and so much more. The life of Ellen Buzand (Yeghisabet Stamboltsian) is the stuff of legends. Her diaries and memoirs remain unpublished in the archives of the Yeghishe Charents Museum of Literature and Art.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: The Resistance of Louise Aslanian

By Arpine Haroyan

From Tabriz to Paris, from resistance to a Nazi concentration camp...this is the story of Louise Aslanian, an Armenian woman whose convictions, commitment and words have largely been forgotten.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: The Prolific Leola Sassouni

By Arpine Haroyan

Arpine Haroyan traces the life of Leola Sassouni, born in a small town in the Ottoman Empire, who would go on to fight for the independence of the First Armenian Republic, dedicating her life to her nation, and leaving behind a rich legacy.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: The Tragedy of Maro Alazan

By Arpine Haroyan

The four tragedies of Maro Alazan based on her unpublished memories- Genocide, Soviet prison, exile and return from exile. The untold story of an incredible woman and her resilience in life and love.

-----------

1- “Reformer” refers to male intellectuals of the Armenian community (millet) who in most cases worked independently from the decision-making authorities, but who nonetheless influenced the course of the decision-making and governing procedures within the community by creating a public opinion through writing, literary salons, etc.

2- Nukhet Sirman, “Gender Construction and Nationalist Discourse: Dethroning the Father in the Early Turkish Novel,” p. 162.

3- Byouzandion 4493 (1911).

4- Byouzandion 3645 (1908).

5- Տեղեկագիր Ազգային Կրթական Խորհրդոյ առ Ամենապատիվ Սրբազան Պատրիարք Հայրն և առ Քաղաքական Ժողովն Ազգային Կեդրոնական Վարչութեան [Report of the National Education Council to Patriarch Father and Civil Council of National Central Administration] (Constantinople: 1871), p. 4.

6- Entanik 1 (September 15, 1883).

7- Manzume-i Efkar 1370 [December 2/22, 1906].

8- Ibid.

9- Amenoun Taretsouyts (1909).

10- Entanik 6 (December 1, 1883).

11- Entanik 2 (October 1, 1883); Arevelk 2870 (August 27, 1893); Byouzandion (March 12, 1905).

12- Arevelian Mamoul (November 15, 1897), p. 759.

13- Entanik mentioned the insertion of love for simplicity among the five reasons behind the publication of the journal. See, Entanik, 1 (September 15, 1883).

14- Hasmik Khalapyan (2009), "Nationalism and Armenian Women's Movement in the Ottoman Empire, 1875-1914" (PhD Dissertation, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary).

15- ibid.

16- See, Hasmik Khalapyan, “Women’s Education, Labour or Charity? Significance of Needlework Among Ottoman Armenians.” Women’s History Magazine 53 (Summer 2006), pp. 21-31.

17- Manzume-i Efkar 1491 (May 4/17, 1906); Arevelian Mamoul (September 13, 1908).

18- Sami Zubaida, “Islam, Cultural Nationalism and the Left.” Review of Middle East Studies 4 (1988), p 7.

19- Yeghia Demirjipashian, Աղջկանց դաստեարակության բրայ մի քանի խոսք։ [A Few Words on Girl’s Upbringing.] (Constantinople, 1890), p. 21.

20- Ibid, p. 205. My emphasis.

21- Byouzandyon 2598 (March 29/April 11, 1905).

22- Tsaghik (1897), p. 99.

23- Grigor Zohrab, §Ø³Ûﳦ. [“Mayda”]. Yerkragound 10 (October 1883), p. 306.

24- Arevelian Mamoul (January 1894).

25- See, for example, the play by Aram Antonian (penname Mercedes) entitled Ֆեմինիզմ [Feminism!]. Tsaghik 3 (October 25), 1905.

26- Arshak Alboyajian, Ուսումնասիրութիւն Սրբուհի Տյուսաբի։ [A Study of Serbouhi Dussap’s Works]. (Venice: 1901), p. 19.

27- Massis 32 (August 11, 1901), p. 510.

28- Arevelian Mamoul (October 15, 1900).

29- Yuval Davis, p. 45.

30- The terms is borrowed from Afsaneh Najmabadi, “The Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and the Ideology in Contemporary Iran” in Women, Islam and the State, ed. Deniz Kandiyoti. (London: Macmillan, 1991).

Comments

Flora Wiegers

3/9/2020, 6:39:47 PMI learned so much from reading this post. I’m Armenian born and raised in Iran, and now I am a US citizen. I would love to read the memoirs and writings of all our past feminist sisters. Why haven’t they been published? This is extremely important.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.