The 268 kilometres of barbed wire, miradors and Russian soldiers that separate Eastern Armenia from Western Armenia is a tragic frontier. It serpentines over deep ravines and canyons, along the Akhurian River, over steppic wasteland. It cuts through Ani, the medieval capital of Armenia, hence severed from the Armenian people by the architects of the Treaty of Kars in 1921; Atatürk traded off the Black Sea port of Batumi to the Soviets for this Armenian symbol. The future president of the Republic of Turkey knew how to deal with historical heritages that piqued Turkish pride, impinged on the rewriting of Turkey's history, that trespassed the frontier of and encroached upon the glorious role of the Turks in their history.

That tragic frontier also separates from Eastern Armenia the extraordinary monastic complex of Horomos, founded on an ox-bow section of the Akhurian River some 20 kilometers from Ani (and only several from the frontier) in the 10th century, and which today is out of bounds to everyone.[1] The church of Mren fares no better, cleaved from Eastern Armenia by several kilometres of steppe lands. The Haykadzor Church had rotten luck (as so many other nameless Armenian churches strung out on that 'natural' border). Ensconced between two barbed wire barriers, out of bounds to Turks and open only on Sundays for morning mass to Eastern Armenians, this proud jewel lies ever so stoically, embalmed in its lonely casket.

The Church of St. John.

The Churches of Saint Menas and St. George.[2]

Varak Ketsemanian's essay, The Conceptual Gap: The Case of “Western Armenia” inspired me to write this short article. Being neither Turk nor Armenian, and having travelled and lived extensively in both Eastern and Western Armenia for over 12 years, I believe that my vantage point as an 'outsider' offered me splendid opportunities to plunge into the complex network of Turkish-Kurdish-Armenian relationships in Western Armenia. This vantage is not neutral; my articles and essays and book on Turkish-Armenian relationships bespeak my position. Perhaps the Turks, the Armenians and the Kurds have always seen me as an ‘uncommitted outsider,’ as an ‘objective researcher.’ Now if that is what those three aforesaid communities have thought of me during my 12 years of living and travelling in Western and Eastern Armenia, so much the better: I had no objective reason to convince them of the contrary.[3]

Indeed, I spent many of those years traipsing along the two sides of that tragic frontier. Tragic for several reasons: Western Armenia has been settled by a stateless Kurdish population whose instinct of survival over the centuries has driven them to ally themselves, ideologically or militarily, with foreign powers, and because of those exogamic allegiances, has provoked the ire of the Turkish government, who in retaliation has led and still leads punitive expeditions into the Kurdish territories, destroying villages, murdering ‘traitors,’ tracking down ‘terrorists.’ Since 1923, Western Armenia has been and continues to be the theater of a merciless struggle between Turk and Kurd, which has prevented any ‘human narrative’ between Armenian and Turk … between Armenian and Kurd. For according to Turkish officials, any contact between Armenian and Kurd in Western Armenia implies foreign infringement in their internal affairs, and it goes without saying, any 'prolonged' contact between Kurd and Armenian can be instrumental for the Kurds as an ideological support in their struggle, however slight or meaningless that support may appear to us. For it is never slight nor meaningless to the Turkish authorities.

Tragic, too, because of the suspicion that enshrouds the minds of both Kurds and Turks living in Western Armenia. On my voyages there in the 1980s and 1990s, difficult years politically and militarily between Turks and Kurds, a time during which few or no Armenian from the Soviet Union travelled in Western Armenia, nor many for that matter from Istanbul, the first question put to me by the Turks or the Kurds was whether or not I was Armenian! No, I was not. The second question was whether or not I had come to Eastern Turkey to photograph and do research on ruined Armenian churches for political reasons! No, as a professor from the Bosphorus University in Istanbul, the photos and my research were to be part of a photo exposition on Medieval Christian Art in Eastern Turkey.[4] It goes without saying that it was only normal that they suspect me of diffusing propaganda against them. Once, however, reassured of my ‘sincerity,’ they left me to my investigations, and on sundry occasions helped me in discovering those churches and monasteries whose location on my maps was erroneous or access to them difficult.

The Turkish and Kurdish discourse concerning Armenians and/or the remains of their ‘lost homeland’ has never been a sympathetic one neither prior to the founding of the Republic of Armenia nor after it. To recover that 'lost homeland' seems to me a futile, hopeless fantasy, given the suspicion, contempt, fear and hate that has enshrouded the inhabitants of Western Armenia since 1923. All these emotions arise from the continual conflict and war between Turk and Kurd. Atatürk's Republic had no place either for 'traitorous' Armenians, hence their religious places of worship, nor for the plotting Kurds bent on founding an autonomous or independent state. Only those Armenians who changed their names, who feigned suffering from amnesia, who 'turned the page' of the past and set their eyes upon the bright ray of hope of Turkish Republicanism were left, more or less, unscathed to partake of the shiny rays of History in the making. Similarly, only those Kurds who sang the Republican jingle, who adhered to the Turkish language and dress and code of conduct were allowed to live in peace. No word of Kurdistan was to slip through their lips. Neither a word from their language![5] As to the Armenians, always a thorn in Atatürk's side, albeit there were hardly any of them left in Western Armenia, besides those converted to Islam, their forlorn monasteries, churches and chapels that lay dormant or dead would play no role in that bright, new Republican History, and consequently, left to their fate! If today the visitor chances upon them on the steppes, in the villages or within the 'urban landscape' of Western Armenia that is because the Turks and/or the Kurds found excellent use for them. Those that have long since disappeared from Western Armenia, unfortunately did not find either use or favor in the eyes of the Turkish Army or the Kurdish population. So as I journeyed from village to village, from monastery to monastery, visiting many two or three times over the years, the same refrain was repeatedly sung to me: whenever I spoke to a Turk, the Armenian Genocide became the horrendous doings of the Kurd. And whenever I spoke to a Kurd, those tragic butcherings were perpetrated by the Turks. Many Kurds even went so far as to call the Armenians their 'dear brothers' … To listen to those refrains whilst gazing upon the gutted churches and monasteries, or upon the expropriated Armenian homes aroused a sense of utter hopelessness as to any possible 'human narration' amongst the inhabitants of that desolate land. I believed (and still do) that humaness had/has all but vanished from Western Armenia. Be that as it may, I shall now expose several reasons why many ecclesiastical edifices remain erect, and why partial or full restoration and/or the official upkeep of them has been effected.

The foremost reason is functional. The excellent workmanship of which the Armenian artisan is noted for did not escape the eye of the Kurds or the Turks when they settled down permanently in the abandoned Armenian homes or chapels, when they built or rebuilt their own homes on the deserted lands left to them by the deported or murdered Armenians. How many intact chapels or churches were converted into mosques? Into chicken pens, cow sheds or grain storehouses? How many underwent a dual transformation: the upper part of the intact church became the mosque by simply putting down a false floor, white-washing the frescoes and removing holy relics, whilst the lower part lay abandoned in utter darkness? How many deserted Armenian houses became Turkish or Kurdish homes?[6] That being said, many Turks or Kurds preferred to build their own homes: How many nicely cut 'Armenian' stones did I see fitted into the cement or mud-brick walls of Kurdish or Turkish homes in Western Armenia? Many still had Armenian inscriptions on them. Church stone was also extensively used if the dynamite was powerful enough to dislodge them. When invited into these homes, and enquiring about their particular history, the owners informed me that they had purchased them from their former owners (never specified as Armenians), who had long since emigrated to Europe.[7]

The Turks and the Kurds of the villages of Western Armenia are very practical people: Why destroy a church or a chapel when the space or the stones can be used? Why even demolish a church or chapel? Witness Ani, where mosques lie beside churches whose façades have never been transformed, profaned or gutted, as if the soil upon which they had been erected was sacred, and any irreverency or sacrilege towards that soil might provoke the anger of God! Less reverent, but just as practical minded has been the recent restoration, partial or full, of certain ecclesiastical edifices, authorized by the Turkish government but financed by the Armenian community of Turkey.

It must be said here that the full restoration of the Patriarchate of the Holy Cross on the Island of Aghtamar near Van is not due to any love of Armenian culture on the part of the Turkish authorities. It has indeed been nicely restored, and has even witnessed several baptisms (under heavy Turkish police surveillance). Yet, it will never be a church: it remains a museum, and money must be paid to visit its island residence. The restoration of the Church of the Holy Cross has brought to the surface the ambiguity of Turkish-Armenian relationships. Penitence? Contrition? Hardly… It is a gesture which forms part of a modern Turkish discourse that seeks to redeem or rehabilitate their 'bad conscience' by offering a modern image of the Turks to the outside world as guarantors or sponsors of 'their' Armenian cultural heritage whenever the 'question' of genocide is evoked during international meetings, debates or conferences. Similarly with the Kurds, whose modern discourse has weaved a fine thread of 'sympathy' and even 'empathy' towards their Armenian 'friends'[8] and whose role as caretakers of the ruined churches and monasteries in their mountain villages is also not without ulterior motives, but of a very different nature.

Let us take the case of Varag, since Ketsemanian mentioned it in his essay. Varag Vank is situated some 20 kilometres from Van in its mountainous village. There is no doubt that Mehmet or any other Kurd, do keep serious care of the monastery. Mehmet and the villagers are quite aware of its importance for Armenians, albeit they may ignore its despicable destruction after the battle of Van by the Turkish Army in 1915. In the 1980s there were few visitors. Today, it has become quite a tourist attraction[9], and rightly so, the frescoes on the pillars of the jamatun are of extraordinary beauty and workmanship; it was as if the bishops painted on the pillars stood as the 'pillars' of the Armenian Church! As I said, Mehmet is fully aware that what he is watching over is of Armenian heritage, and with this knowledge, and the knowledge that the greatest existential enemy of the Turk remains the Armenian, to curry favour with 'the enemy' is the surest way to pique the Turks, to antagonize them, to exercise a strategic, psychological advantage over them by 'siding' with the 'boogeyman' as Taner Akşam has so eloquently phrased it. The Kurd, thus, will go out of his way to preserve those very symbols that the Turks, overtly or secretly loathe.[10]

Varag Church: Bishop as Pillar of the Church.

Varag Church: the Jamatun.[11]

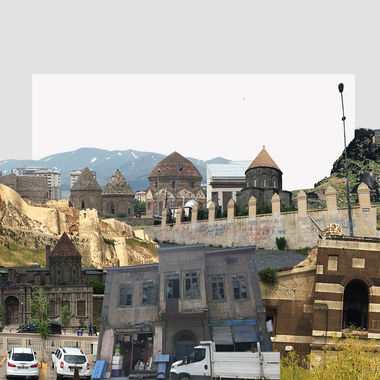

Ketsemanian also mentioned Kars. The history of the 10th century Saint Apostles Cathedral is worthy of a brief word or two. I visited Saint Apostles three times: in the 1980s it was principally used as a public toilet; notwithstanding, the Russian iconstase was perfectly intact. The visitor had only to be cautious when strolling about inside, and breathe as little as possible due to the bestial stench. On my second visit, perhaps in 1990, the side-portals of the public toilet had been cemented up, off limits to all. Finally, on my last visit, not only had the cement been removed and the church floor swept properly, but the Kars municipality had published postcards of the Cathedral with the heading 'The Museum of Kars.’ From public toilet to museum: some may call that progress, perhaps, but a church it will never be.[12]

Restoration and careful watch over churches or monasteries have also offered Turkish authorities and local Kurds commercial possibilities, not exactly lucrative, for few people visit these ‘sites,’ but nevertheless many means of earning a bit of money. First of all, listed officially as museums, the visitor must pay an entrance fee. Second, organized tours have developed, especially in and around Van Lake, where local organizers have opened agencies, hotels and restaurants for visitors. The Eastern Armenian who visits these 'museums' is quickly reminded that their former ecclesiastical function no longer exists, and that their existential shift into museums or tourist sites signifies a subtle expropriation and shift of their ontological value. Armenians who come to Western Armenia are not worshippers but tourists! Not pilgrims but clients...statistics! Gudutz Island, one of the four remaining islands on Lake Van, houses one of the most remarkable Armenian gems of the Middle Ages: the St. John the Baptist Church.[13][14] I managed to reach Gudutz Island in 1989 thanks to the Kurds of the village of Ganjak;[15] the young boys motored me to the island in their fishing boat, a lovely four-hour voyage. Other than the hundreds of seagulls, the island was deserted, and I had many hours to explore the church and its environment.

Today, there are organized visits to Gudutz and its church from the town of Van, a small but attractive tourist site for foreigners who venture there. Undoubtedly, from a Turkish and Kurdish point of view, to develop tourism to these former places of worship is the best way to 'clear' their bad conscience, whilst burying the primary function of their existence: a place of religious worship. Now some Armenians may think that this alternative is better than their entire destruction or slow decay… perhaps. But a better alternative cannot constitute a 'human narrative.'[16]

The Island of Gudutz: The Church of St. John the Baptist viewed from the crest of the mountain (1990).

Quite frankly, I do not see any hope for 'a human narration' between Western Armenia and Eastern Armenia. For the writers of this narration of the future must have mutual interests and not unilateral ones if there is to be any relationship at all. Presently, both Turks and Kurds have very opposing interests in a discourse with Armenians: Turkish interest to appease tensions after tragic events such as the assasination of Hrant Dink. Kurdish interest to ruffle the susceptibilities of the Turks by 'sympathizing' with the 'persecuted' Armenians. There have been so many lies and false promises between Kurds and Turks that I do not see how any Armenian from Eastern Armenia or from the Diaspora could enrich this narration with his own (H)history without getting hopelessly ensnared within the complex quagmire of Turkish and Kurdish ideological and political interests. In the political world there are no friends only interests! And Western Armenia has always been a heavily politicized region. Armenian ensnarement in this inextricable swamp may lead to the question of where the primary 'conceptual gap' lies: among Eastern Armenians as regards Western Armenia or within the dangerous vortex of the political reality of Western Armenia whose actors - Kurd and Turk - would not hesitate to have recourse to 'outside' influence either as an instrument of support or as a pawn to be ultimately sacrificed? There is no place for a 'human narration' on this ideological and military battlefield, for a battlefield it is.

Armenian medieval art and architecture which lies on this battlefield is a relic of the past, a mere chapter in a History that has been closed since 1923. What remains are museum pieces to be occasionally displayed for the curious or naïve Westerner, for the Christian orders of Istanbul - Latin or Armenian - for those Eastern Armenians who believe that the Turks and the Kurds are honestly interested in dialogue, in promoting a 'shared cultural heritage.’ This is an illusion. As illusory [17] as recovering a 'lost homeland!’' An illusion that has been embedded in the recesses of the Eastern Armenian mind since 1923, and is presently being rekindled by the recent spurts of restoration, care-taking and conferences on the 'Armenian Question.’ [18] For the Turks and the Kurds, Western Armenia remains a land of the past; it is Eastern Turkey that the Turks are battling to maintain at any cost, and it is a true autonomous Kurdistan that the Kurds are struggling to gain! Neither Turks nor Kurds have any intention of engaging in a 'human narration' over Western Armenia with Armenians … for now ...

The Other Side of the Frontier

Let us now cross the border (by way of Georgia since the frontier is closed) to the other side of the frontier, on the Eastern Armenian side. This side has always astonished me as I walk along it through villages like Haykadzor, where the Eastern Armenian discourse bubbles over with irony and disgust of the Turk and the Azerbaijani, where it reaches a zenith of hatred as the villagers point to the spiralling minarets seen with the naked eye over the ubiquitous barbed wire and miradors and exclaim, “We'll have none of that here!” Where fear that the Turkic and Kurdish hordes may stampede across that border - if ever it opens - and swamp the tiny Armenian population with their numbers.[19] Where the intolerable thought of inter-marriage with those invading male hordes would deprive them, strip them of their Christian daughters. These discourses ring in my ears as I hike or hitch-hike along that barbed wire frontier. It is a discourse of desperation, but also of pride; for have not the Armenians survived the horror of Turkish and Kurdish genocide? Have they not defeated Azerbaijan (and its mercenary allies!) in their war for Karabakh?

These discourses flow not from bad conscience but from Memory. A Memory that proudly recalls that for the one General of every Azerbaijani village, the Armenian village possesses four! At Haykadzor, and through the other villages I walked through along that frontier, I recall a whole scale of discourses of the most polyphonic nature: the discourse of indifference, of irony, of contempt, of incomprehension as to how Turks visit and work in Armenia and Armenians visit and work in Turkey, when in fact the frontier is closed, and their respective governments hardly engage in any fruitful dialogue. Indeed that may be the most tragic consequence of the closed frontier. [20] So many discourses whose basic framework, however, was their variegation. Even those discourses that seethed in dislike of Turks, Kurds, Azerbaijanis or Moslems in general offered me - that 'objective observer' - a feeling that these discourses were voiced by individuals and not by any Voice of Authority. For this reason their inflections were polyphonic, and not the parroted refrain of sanctimonious sponsored ideology.

Along this frontier the pilgrim espies from afar, with a good pair of binoculars, several churches of Ani, pathetically arising from hill-tops or hunched up upon desolate steppes. Their slow but steady decay, in spite of spurts of restoration, bears witness to the inexorable effacement of a symbol. The medieval gems of this marvelous city shine only for those whose eyes perceive this symbol; and as we all know, symbols outlast the mortal coils with which they had been robed. The research of the Soviet polyglot and intellectual Nicholai Marr can be read on a metal board from whose platform Ani's churches and monasteries are visible on a clear day. I attempted to locate the exact position of Horomos from the Eastern Armenian side but without much luck: the soldiers stationed in the miradors waved me off as I made my way along the dirt track that skirts the barbed wire. Besides, the monastic complex is located in a deep ravine, and surely cannot be detected from the plateaus. Be that as it may, I believe I caught a glimpse of the Church of Zak'aria, perched upon its solitary hill-top.

Haykadzor Church imprisoned between two barb-wire barriers (2015).

Surp Zak'aria situated on the Peninsula of Kız Kalesi at Ani.[21]

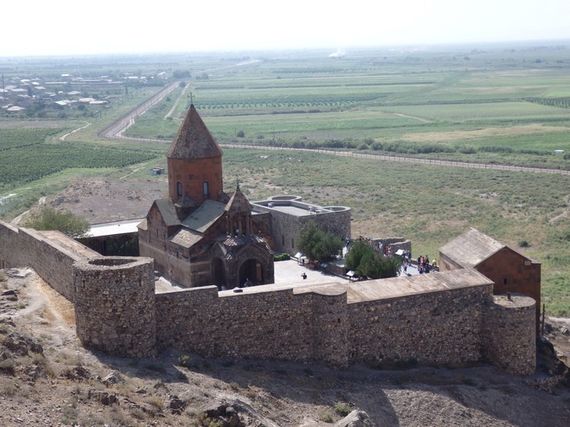

Along this frontier, too, the pilgrim discovers Khor Virap, only several meters from the Turkish border, a wonderful church barely salvaged from the insensitive Turkish and Soviet architects of the Treaty of Kars. Khor Virap cannot be demolished nor profaned; its stones cannot be used to build Turkish or Kurdish homes. No Kurdish carekeeper will impress the visiting Eastern Armenian of his faithful upkeep, or accept money from the visiting Armenian from Istanbul.[22] There it rose, so tiny against the enormity of Mount Ararat, her guardian angel. Mount Ararat: symbol of Armenia? Which one: Eastern or Western? To peer out upon those plains lying at the foot of the immense skirts of Ararat from atop the terrace of Khor Virap substantiates the vision of the geographical and architectural unity between medieval and modern Armenia. It is Ararat that joins both Spaces, both Times. Ararat is the center from which radiates the energy that unites both Spaces and Times into One. For it is the visual union between Khor Virap and Mount Ararat that forges that symbol; it makes little difference on what side of the frontier it lies. Its august grandeur encompasses both Western and Eastern Armenia, and whose shining snows illuminate the way to the future for those who have eyes to perceive them.

Along this frontier, too, the pilgrim beholds one of the most impressive jewels of the medieval Armenian stamp: Yereruyk Church located in the village of Ani-Pemza. It lies a mere three meters from the low barbed wire barrier. Yereruyk dates from the 5th or 6th century. There is no doubt that this work of unrivalled craftsmanship is of Syriac inspiration, perhaps Northern Syria, whose archetypes may be found in Riha or in Turmanin, judging from the triple portal-entry, the middle portal of which is framed by two pillars surmounted by a 'moorish' arch and two capitals. Above this triple-portal, two windows have been built over the two sealed portals directly below them; they, surmounted by horseshoe arches, have been beautifully decorated with flowing striations. Above these ornamented apertures is yet a third storey, crowned with a three-horseshoe arched-opening supported by two pillars, again ornamented with striations or ribbons. The façade consists of six apertures: three lower, two medial and one top as if, symbolically, the Three are One, from bottom to top, (a worldly perception), or the One is Three from top to bottom (a cosmological perception or order). The sight of this church is awesome, and the pilgrim must thank God that it too has been salvaged from decay or destruction, unlike the fate of Mren, Horomos, the 1001 churches of Ani and so many of the other so called Red Churches, victims of indifference, forsaken to fend for themselves, either used as shooting targets by the Turkish military, or periodically admired like remote relics for the odd visitor, if and when visits are allowed by the Turkish Army. For indeed the Turkish authority can and will forbid any visits to these relics if it is decided that any 'trespassing' into military zones will impede their myriad military operations against the 'terrorist' Kurds in the area. This happened to me at Albayrak when I was refused permission to photograph or even see the 10th century Church of St. Bartholomew. I was most fortunate indeed to have spent many hours at Horomos, a privilege that is no longer possible.[23]

Khor Virap against the backdrop of Mount Ararat (2015).

The fabulous façade of Yereryuk Church at Ani-Pemza (2015).

The village of Ani-Pemza lay in absolute silence simply because there was hardly a soul there. A villager from whom I asked directions made no mention of the frontier, nor of the Turks. Neither did he comment on the church. It was as if he had lost interest in the church, it standing so desolate, so lonely. Apparently, many villagers had 'migrated' to Yerevan, abandoning their church to the auspices or aegis of Western institutional funds that enable 'underdeveloped' countries to preserve and restore their national heritage. This last sentence is meant to be ironic. Only the Armenians possess the craftsmanship, will and finances to preserve and restore their national heritage. The time will come when they turn their eyes and talent to Yereruyk. Armenians have no need for 'charitable' mentors… to be patronized...

A Final Word

Western Armenia or Eastern Turkey? This 'lost homeland' has been a thorn in Turkey's side since 1923; why pull it out by attempting to 'reason' with the Turks or the Kurds? The thorn reminds the Turks and the Kurds of a people who lived and thrived in Turkey, and who played an enormous role in the unfolding of Turkey's History, and this in spite of the silence, scorn and distortion voiced by Turkish intellectuals and historians. Western Armenia is the Memory of Armenians; Eastern Turkey is the bad conscience of the Turks and the Kurds! Memory should not be interpreted as wistful nostalgia here, but as a responsibility towards the Past (and not just one's past!), as a vocation to the voices of that Past, however faint their muffled murmurs reach our ears.

The thorn should be sustained, driven deeper into the flesh of the Turkish side until they acknowledge the genocide of the Armenians of Eastern Turkey and avow openly, politically, to the full participation of Armenians in the making of the History of Turkey. There is no compromise to be made here, nor sympathy to be shown if this avowal is denied or rebutted. If and when the genocide is recognized, then there may be room for compromise and sympathy; that is, for diplomacy and dialogue. Dialogue signifies mutually acceptable political and cultural exchange; bilateral acquiescence of each other's role in Western Armenia or Eastern Turkey. It is thus senseless to dream of recovering a 'lost homeland.' This is sterile or hollow nostalgia, more a nightmare than a dream because it prevents the dreamer from seeking horizons which only the future can make emerge. On the other hand, if the genocide is acknowledged, it is then quite sensible to believe in and hope for the restoration of certain monasteries and churches, and the gradual opening of their doors to Armenian worshippers from Eastern Armenia, Istanbul and the Diaspora. Churches then will become lieus of faith and not museums. Armenians and other Christians will then become pilgrims and not tourists or clients. Perhaps at that time a true 'human narrative' will be written by which the Armenian is recognized as an actor of that narrative, and by that recognition, uncover or dig up his or her narrative identity within that 'lost homeland' with and among those who are presently living there: Kurds and Turks. For now, Turks and Kurds are locked in terrible ideological and military warfare that Eastern Armenians should avoid. It is not their battle. Why be dupe to the interests of certain parties, and be bartered like pawns in their merciless game?

There is certainly a 'human narrative' to be acted out and written down in Western Armenia by Armenians of the Republic of Armenia, by those Armenians, too, living in Turkey or residing abroad. [24]But before this narrative is written, a genuine identity must be forged, not as a tourist who visits museums or remote relics of the past, but as a pilgrim of faith who prays in their places of worship without surveillance, without fear, without the onus of Turkish and Kurdish bad conscience.

An equitable and shared Memory of the Past is what peoples and communities of very different origins have written within the framework of their countries. These narratives constitute what is called History. Neither Turks or Kurds are ready to write their narratives with Armenians, and for this reason no History of Turkey has yet to be written. It will be written the day the Eastern Armenian convinces Turks and Kurds that to open a frontier demands the cleansing of one's bad conscience. That tragic frontier is Turkey's bad conscience: the Armenians need not console them nor sympathize with them. The very existence of Armenia - Western and Eastern - is enough to remind them what that cleansing entails. It will be long, but a bad conscience has never triumphed over Memory.

The Cathedral of Ani before the Earthquake in 1988.

The scant Remains of the Hermitage of St. George on the Island of Lim (1990).

-------------

1- I visited Ani and Horomos twice: in 1988 (photography was prohibited!) and in 1990. In 1990, thanks to a rather indifferent Turkish military officer, and to the dismantling of the Soviet Union, Horomos lay in a sort of no man's land ; I was able to roam about it for an entire day. As to Ani, photographing the churches was allowed in 1990.

2- Photos taken in 1989.

3- Just as a matter of fact: I spoke Turkish to the Turks and Kurds of Western Armenia and Russian to those Armenians of Eastern Armenia. I spoke very little Armenian, and learned only to read with, however, great difficulty.

4- Exposition which took place at the French Institute of Istanbul, the first of its kind, in 1990. My wife and I sold 88 photos to Armenians and to Turks. Photos of the Georgian and Syriac medieval churches and monasteries were also exposed.

5- Many Turks, intellectuals included, truly believe that the Kurdish language is a dialect of Turkish.

6- In the one or two homes where I was invited to stay by the Kurds, I was amazed to discover that their very numerous families only occupied the first floor of two-storey houses, albeit the second floors, and stairways that led to them, were perfectly intact. When I asked them the reason for this choice they simply shrugged their shoulders ...

7- The greatest fear of the Kurdish or Turkish owner of these expropriated homes is that the Armenian owner - the boogeyman - will emerge from the obscure mists of time to reclaim them. This fear, of course, is quite irrational, but effective enough to haunt the restless nights of the bad conscious of those owners ...

8- After all, are they not victims of Turkish persecution, massacre and humiliation, too?

9- Many Latin Christians who reside in Istanbul visit Varag Vank every year.

10- Several notable Armenians of the Istanbul intelligentsia, names that I cannot divulge, travel to the villages and towns of Western Armenian every so often in order to visit the 'keepers' or 'vigils' of the extant Armenian churches. The Kurdish caretakers are given money, not for restoration, but for their sympathy and duty. The Armenians of Istanbul, by these visits and gestures, guarantee an allegiance with the Kurdish communities, however illusory it may seem to the outsider.

11- Photos taken in 1988.

12- Whilst staying at the Kars Oğretmen Evi (House for Professors), I became engaged in a rather lively discussion with the students and their professor from one of the universities of Istanbul about the architectural value of the Armenian and Selujukid monuments of Ani. The discussion turned rather ugly when they discovered my 'penchant' for Armenian architecture, whereas their aim was the primacy and pre-eminence of Turkish architecture. Needless to say, I waived my principals and yielded to theirs ...

13- Founded in 884 and restored in 1621 and in 1759. The khatchkar encrusted in the wall to the left of the entrance still shone in its bright colours.

14- Or Surp Karapet.

15- Where I also visited and photographed a chapel cleaved in two to permit a road to be built, and where further on through the mountains, for some three or four kilometres, one can reach St Thomas Vank, still splendidly erect against the snow-capped mountains and blue waters of Van Lake.

16- During my voyages in and around Artvin I had befriended a Turk who managed to convince the local 'muftar' to rid the Georgian church, Dört Kilesi, of its cows and hay, and sweep it clean. The Turk visited me in Istanbul to keep me abreast of the 'restoration' progress. He did not do this out of any love for the Georgians, for mediaeval architecture, or for my sake ; little did I know that he had been planning to open a restaurant not far from the church in his village, and when I returned some two years later, his restaurant was indeed thriving, thanks to the influx of tourists, mostly Georgians, since the border with Georgia had opened in 1989. On the other hand, little did he know that secretly mass was being performed in the church, which is absolutely prohibited in Anatolia by Turkish law, unless otherwise authorized.

17- In this sense of 'deceitful'.

18- But I can assure you, not in those minds of the Armenians who live in Turkey!

19- In 2008, Haykadzor counted about 528 villagers.

20- In the hostels of Erivan where I stayed, I read notes left by Turkish visitors who hoped for a better future between Turk and Armenian. These scribbled phrases, indeed, may constitute a genuine 'human narration, but only because they spurn any political adherence.

21- According to Nicholai Marr's research and documents. Photo taken in 1988.

22- This being said, Khor Virap is today a tourist attraction, there are no religious services. But since the church is in Eastern Armenia, it is hopeful that in time it will once again become a lieu of religious practice.

23- The same fortune smiled down upon me when arriving on the island of Lim in 1990, where in spite of it being a military zone, I was brought there on a fishing boat by two Kurds and was thus able to spend the entire day photographing and speaking to the drivers who tended their flocks in and out of the Hermitage of St. George (Surp Kevork). Unfortunately, at the end of this fine day, the 'muftar' and two soldiers arrived to 'escort' me, politely but firmly, off the island. Again, they questioned me on my origins and my motives for taking photographs, for stepping foot on that island. And again, because I was a professor from the Bosphorus University and apolitical, we all ended up having tea and discussing not the Armenian 'question', but the Kurdish one! During the genocide, 12,000 Armenian refugees were starved to death by the Kurdish hamidiye who obstructed any form of assistance or food for them.

24- I am thinking of those Armenians who reside in Russia.

Images by Françoise Mirabile.

related

A Conceptual Gap: The Case of “Western Armenia”

By Varak Ketsemanian

“Western Armenia” as a concept is a crucial component of the Armenian national narrative, mostly in the Diaspora. In this article, Varak Ketsemanian raises some questions regarding the Armenian reality’s understanding of “Western Armenia,” its biases and blind-spots. He suggests refining the ways in which we discuss and represent “Western Armenia” in the 21st century.

Turkey, the Kurds and the Generational Trauma of the Armenians

By Maria Titizian

When Turkey launched its military offensive in northeastern Syria, it triggered something in the minds and hearts and memories of many Armenians.

What is "Armenian" in Armenian Identity?

By Hratch Tchilingirian

In the last 100 years, there have been hierarchies of identity and canonical approaches to definitions of "Armenian," especially as articulated, rationalized and promoted by elites, institutions and political parties in the Diaspora and in Armenia. This essay is not a study of identity per se, but about one of the aspects of identity – the “Armenian” bit of it.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published, including abusive, threatening, racist, sexist, offensive, misleading or libelous language. Comments deemed to be spam or solely promotional in nature will not be published. Including a link to relevant content is permitted, but comments should be relevant to the post topic.