Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

"Akhpar drink." This is what many people in Yerevan called coffee when it was brought and then popularized by repatriates who had immigrated to Soviet Armenia in the 1940s. The repatriates were called “akhpars” by the locals, a term derived from the word yeghpayr (for brother) that served to segregate them as the Other.

In the 1960s, the same fate befell the lahmajo, the flatbread with spiced meat popular among a new wave of repatriates. It was referred to as an "akhpar meal" by locals and treated as something foreign from their own cuisine. Now both of these are standard fare and have found their place in Armenian gastronomy. The "akhpar drink" has become "Armenian coffee" with which our days begin, continue and sometimes end, and we proudly present lahmajo as "Armenian pizza" to otars (foreigners).

The repatriates not only brought their resources and enthusiasm with them, but also many culinary traditions that the people of Armenia had already forgotten. Interruption has become a typical occurrence in our history, which is especially visible in food. For example, there is a big gap in the attitudes of diasporan Armenians and Armenians living in Armenia toward food and culinary art. It took about 60 years for the "akhpar meal," which was negatively perceived because of the Arabic roots of the word lahem be ajeen (meat and bread) to become "ours" and enter our everyday life.

We don’t need to go that far back. Only 15 years ago, many dishes were not widely available. Hummus and mutabbal were exotic and confusing to local Armenians, demonstrating the scale of change that has taken place. In the 2000s, it was possible to find hummus in one or two restaurants in Yerevan. Today, one can find hummus in almost every cafe and restaurant in the city, regardless of their menu, from the glamorous cuisine of Ruby on the Cascade to family restaurants Nubara and Dalan on Abovyan Street. Armenian companies are even mass-producing hummus, mutabbal and muhammara, which are now widely available at supermarkets, and at quite affordable prices. There’s no doubt that our gastronomic frontiers are expanding.

Rehan is a Middle Eastern restaurant that opened eight months ago and serves some of the best Lebanese food and desserts in Yerevan. Its manager Harout Okjian has been in the gastronomic business for 11 years and remembers his first impression of the city's flavor profile, recalling how about a decade ago, only shawarma and lahmajo were considered Armenian. “It was difficult to find or explain what hummus or mutabbal were,” Okjian recalls. “And now... people are always looking for new things, they try new things. Armenian cuisine has developed a lot in recent years. People have opened up to new flavors. They accept something new more easily, but that does not apply to Eastern desserts yet. That does not interest local consumers yet."

When it comes to desserts, styles and approaches also differ. Today's local desserts are closer to Europeanized Middle Eastern desserts. If we remember the traditional types and methods of preparation of these desserts, their rich textures, multiple layers and especially the amount of syrup and honey used, it becomes more fascinating as to when they disappeared, leaving us with only baklava. But if we remember the Soviet past, everything becomes clearer.

After World War II, during Khrushchev’s Seven-Year Plan (1959-1965), local Armenians tried to conform as closely as possible to the cultural cues of the Soviet empire. As a result, different approaches to the preparation of desserts began to take shape, and new types of dough were preferred, which had nothing in common with traditional Armenian cuisine. It was during those years that the Napoleon (or mille-feuille) appeared on our tables. It was a reminder of one of the most important events in Russian history—the victory of the “Patriotic War of 1812”—in the form of a dessert. The French mille-feuille was transformed; in this context, it took on cultural undertones as deeply layered as its alternating cream and pastry dough. Napoleon continues to be prepared and eaten in many countries of the former Soviet Union. In this way, slowly but steadily, our culture of sweets shifted from the East to somewhere between the East and Europe, rejecting its syrupy past and embracing a new communist orthodoxy.

Dayk Miricanyan, the owner of the well-known Jash restaurant in Istanbul, representing Istanbul-Armenian cuisine, opened a similar restaurant named Jashag in Yerevan in 2019. He often talks about our acceptance of another, larger culture with open arms. He claims that the Yerevantsi lives “similar to”—similar to a European, similar to an American. “Living ‘similar to’ is a way to stay away from your own, it is a style-less style,” Miricanyan says. “Maybe they are not happy with themselves, are unsure of their life and their attitude."

Perhaps, in insecurity and easily departing from one's own roots, there may be a desire to avoid one's own traumatic and interrupted past—which is most easily accomplished by breaking away from the details in lifestyle that are perceived as tradition. Socio-political traumas are outlined in everyday life and especially in flavor preferences. Perhaps, on the one hand, escaping from our local cuisine to other countries' cuisines, pastas and bruschettas, is because of globalization but, on the other hand, it can be argued that there is also the inner drive to forget our losses, historical interruptions, and life under the rule of other empires.

According to Harout Okjian, Arabic, Armenian and Turkish cuisine are closely intertwined and have greatly influenced each other. No matter how much we try to say “this is mine” and “that is yours,” to divide the famous dishes of the region, it makes no difference. Recipes change depending on political developments, migration patterns and social issues. For example, the Armenians of Istanbul have a seafood dolma, which developed because the ingredients were available to them. This is perceived as strange in Armenia; in Constantinople, because of the proximity to the sea, this type of dish is more organic, both for the mind and the palate.

According to Miricanyan, it is difficult to separate and divide dishes that are considered folkloric; in fact, you don't even need to go in that direction. Instead, you can develop a different way of thinking. "What does Armenian cuisine mean? There can be an Armenian-style cuisine… there is no nation left who can say, ‘This is my dish’… The style is what’s important. You cannot say this produce is mine. The produce and the harvest can change, but the style does not. The dish cannot remain the same. The dish changes with people, is influenced by people, by the environment, by the world," he says.

This approach may seem easier than just taking basturma and labelling it as Armenian, but in reality such a stylistic development is more complicated because it requires self-formulation. This means not only putting the word "Armenian" into broad usage in cuisine, but also, first of all, understanding what we mean by that qualification. Over the past five years, the expressions "Armenian cuisine” or "Armenian flavors" have increased, but they do not focus on flavors, where there is the traditional, Soviet stamp of the 1990s, and so on, but refer to specific dishes.

About 15 years ago, Armenian cuisine was heavily meat-based. Much earlier, plant and dough-based dishes dominated. What is it now? If we look at restaurants such as Sherep, Lavash and Ktur, we see that they present a mixture of traditional and regional dishes, along with dishes common in the Soviet years, in their menus. In such places, ghapama, Napoleon and the beloved roulette of the Soviet era quietly sit side-by-side on the menu, harmoniously integrated into the new idea of "local cuisine."

The peculiarity of the gastronomic business is that it deals not only with wining and dining, but also with shaping culture. In many cases, this is one of the most important factors influencing the stereotypes in people's minds about what a country is like. For example, for us, the French eat croissants and foie gras, Americans love burgers and fast food, and the Italians have their pasta and tiramisu. But all these perceptions and cultural stereotypes penetrate society and circulate, through the gastronomic business.

The menus of Lavash-type restaurants, on the one hand, combine the consumers’ most popular dishes and, on the other hand, show that we are trying to work with our cultural influences and approach the concept of national cuisine more consciously.

The most vivid evidence of this are the dishes on our New Year’s tables. They are diverse and full of foods that have come to our tables from different places. If we try to analyze those tables culturally, we can appreciate the wide heritage that has formed our identity.

Next to the dolma are hummus and tabbouleh, a sign that we have finally emerged from our narrow limitations and are in close contact with diasporan Armenians (or the culture they have imported). Napoleon is to the left of the hummus. On the other side, is a tangerine and lemon cake, which has not left us since the collapse of the Soviet Union—though it became a tad sweeter in the 1990s. We may also find baklava on the table, a reminder of our eastern roots but, no matter what, there will definitely be some exotic and "luxury" dish that will scream out our social status.

On the other hand, perhaps the abundance of our New Year tables and the desire to serve rare delicacies again comes from the unresolved trauma of the scarcity during the Soviet period and even earlier. The abundance and quantity of dishes is a trauma of the hunger and poverty of the 1990s, which, intertwined with a history of scarcity, has given us our New Years table. In that amazing spectacle that requires a few weeks of suffering and a lot of money, one can find an abundance of contradictory flavors and smells, but not a developed culture of dining.

Festive tables can reveal a lot about where and in what format our society envisions itself. Is it sun-kissed or not? Heavy and sorrowful or light and full of the desire to live? Ostentatious or self-sufficient? Attached to its roots and traditions or separated from them? These seem to be abstract, theoretical, or even non-food related issues, but they can be formulated even in the most ordinary and apolitical space—at the dinner table. As Miricanyan of Jashag notes, "A lot starts around the table, and a lot changes… the table is a cultural center of sorts.”

Culture, with its colors, smells and flavors, is one of the most important building blocks of the idea of home and community. For more than 30 years, we have been trying to create a home that is comfortable for us, from which we do not want to run away and to which we will return.

Et cetera

The EDM Kitchen։ Electronic Dance Music in the Context of Gender

By Eva Khachatryan

Electronic dance music, as a relatively new cultural phenomenon, could have been occupied by women, but even here, the presence of men is predominant and women have to fight for fair representation.

Did the Wind Drop? Nora Martirosyan's Optimistic Drama From Artsakh

By Sona Karapoghosyan

Director Nora Martirosyan’s film “Should the Wind Drop” reveals the frustrating situation surrounding the airport as a starting point to delve into the history, problems and spirit of Artsakh.

Rediscovering the Body: The Painful Birth of Post-Soviet Performance Art

By Varduhi Kirakosyan , Vigen Galstyan

Although performance art has practically disappeared from the contemporary art scene as an autonomous medium, early practitioners had a profound impact in changing perceptions of the body in Armenia’s post-independence culture.

Notes From a Future Museum: The Aesthetic Politics of Armenian “Chekanka” Art

By Vigen Galstyan

Hybridizing fine art and mass culture, Soviet-era “chekanka” art generated an unconventional visual world in which ancient and modern mythologies, as well as sexual and political desires could be blended into a patently local cultural narrative.

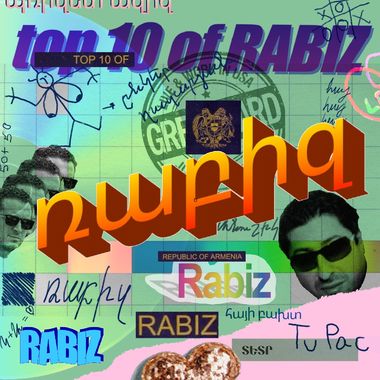

“Michael Jackson, Know This Well, I Can’t Bear This Pain”

By Karen Avetisyan

The “Top Ten of Rabiz” was a series of albums produced by a group of young men trying to reproduce the scattered reality of the 1990s through the language of music and an experimental format that was never really “rabiz.”

Back to the Future: The Evolution of Post-Soviet Aesthetic in Armenian Fashion

By Anais Gyulbudaghyan

The Armenian love for following trends is something that is a part of the collective cultural and political history. And that tendency became stronger after the collapse of the Soviet Union.