The trip to the military post is surprisingly short. Before leaving Stepanakert, I packed a box of food, cigarettes, coffee and American gum for the soldiers on Artsakh's border with Azerbaijan. This care package is a ceremonial gift. There is nothing that I can give these young men who defend the line drawn in blood, the line of contact, to show my appreciation. These boys place their bodies in defense of Armenian lands against an aggressive regime, to protect the children that will continue to serve and care for their home for the next generations to come. "The Line of Contact," they say. It is terminology that leaves many uninformed confused. "Why not call it a border?" they ask. Exactly, I think, why not?

I am transported by my military escort from Stepanakert to the meeting place, a military building surrounded by the deafening sounds of birds. The rest is silence with occasional ruffling of leaves of the surrounding trees. The officers, who are bringing me to the first line (the one closest to the Azerbaijani military) quickly transfer the box of gifts from the civilian car to the back of the military vehicle. In a few minutes we are on the road through what looks like wheat fields, golden and rolling, reminding me of the film "Gladiator." My trip companions explain to me that people still farm this land, despite the proximity to the Azerbaijani military and the sprinkling of "M"s throughout the buffer zone from the civilian population of Artsakh, which indicate a minefield. "M is a minefield," I repeat in my head, as I look out the window and see them everywhere. What am I doing here, a mother of two, a wife, a daughter? My parents brought me to the U.S. to be safe from Azerbaijan. And here I am in a military vehicle heading toward the same hatred that left me homeless and almost dead 29 years ago.

The fear of going to Artsakh surfaced several months before my first trip there in 2014. I began planning the details of the trip to return back to Armenia, 22 years after leaving it as a refugee from Azerbaijan. As I was coordinating my official visits in Artsakh, several people in the U.S. cautioned me that it wasn't safe. They told me to register with the U.S. Embassy in Yerevan, which in turn warned me that the U.S. Government will not be able to offer me any protection if something was to happen to me within Artsakh’s borders, whatever that something was. The fear of being hurt or killed by the Azerbaijani military in a "war zone" was due to misinformation, and to my own ignorance of the region, as much as it was due to turbulent memories of escaping my home as an Armenian in Baku at 11 years old.

It was clear: I couldn't speak about something in depth as I had been speaking about Artsakh without having ever seen it. And you really have to see it for yourself.

In the privacy of my own thoughts, when I was truly honest with myself, I felt like a hypocrite, drowning in my own ignorance and fear. But the determination was building. I ignored the naysayers, sometimes even my own family members. "So what, you are afraid," I thought to myself, "Imagine living there." And with that determination I finally went to see the beauty of the land and the people I have been speaking for and about worldwide.

That first trip was life-altering and I couldn't get enough. For the first time in my adult life I felt like I belonged somewhere. And every year since then I went back, sometimes twice a year. And with each visit to the land, I understood more and more that the best way to make Artsakh thrive is to physically enter it. The Motherland and its child both benefit from the experience. It sends a strong message to the people that live there and to the world at large. You have to smell that air to feel connected to the roots. You have to meet the Artsakhtsis to understand their drive, to get that urge to work twice as hard, ensuring their story is told and not forgotten. You have to contribute to its economy directly and grow the confidence in it both internally and externally. This is the most effective way to help Artsakh.

But being in Artsakh and being on the line of contact are two separate universes. Artsakh is safe for travel, welcoming visitors from all over the world year round. Its tourism is thriving. But the line of contact is off limits to most civilians and visitors. The idea of going to that violent place where mothers lose their babies, where Artsakh meets Azerbaijani military, lingered in my mind for about a year. I saw it from afar last May while driving up the hill to Tigranakert fortress. We exited the vehicle long enough to take a cheeky photo pointing to Azerbaijan. I looked over my shoulder to the dark line of contact and Azerbaijan beyond it. What was meant to be silly, and maybe a little coy, made me extremely emotional. This is the land where I was born, the land that banished my family and killed my neighbors. I thought of how close I was to it, the closest I've ever been in 29 years and my eyes wandered far beyond the dark line. I thought about all the boys that die protecting ancient Armenian lands, and how vulnerable and endangered Artsakh is because of the regime that rules my former home. I was startled from the second long daydream when a sudden urge to hide took over my body – will they see the shiny white SUV we were in, perched up on the side of a hill? Will they blow it to pieces? After all, during the April War in 2016, Tigranakert had come under fire. The shells from the aggressor are displayed in its museum now.

When I came back to the hotel, I reluctantly posted the photo to Facebook along with all the photos from the day. After their initial horror subsided, I reassured my parents and my husband I was safe and I was now in my hotel room. They scolded me for being irresponsible to ever get that close to danger. I laughed it off and said they were being overly emotional. But when I was falling asleep that night I knew that I now understood what it is like to live like this, to worry over your safety daily and feel the danger for the kids on Armenian borders walking to their village schools completely aware of this reality. I thought of farmers that can't farm their lands because of enemy snipers firing at civilians for two decades now. I thought of children blown up by mines that the HALO Trust is working so hard to remove from Artsakh lands. I wasn't just reading about this; I felt this danger on my skin. The international community calls this ceasefire. Their naming conventions are a curious thing. Nothing ceased in Artsakh. There is nothing frozen about this conflict. It is always on fire.

During my next trip to Armenia, among several University lectures, I visited the rehabilitation center in Yerevan where many wounded heroes of the April War and other incidents on the line of contact receive medical treatment. It was eye opening to see these young men, some not even 20 years old, with such debilitating and life altering injuries. They weren't just names that ANCA diligently posts every time there is a death of a soldier. They were real college age kids, forever scarred. Many of their friends died, and they knew they were lucky to remain alive, but life will be a difficult journey for them. Armenian Wounded Heroes Fund (AWHF) is an organization based in the U.S. that funds the rehabilitation of these soldiers and also supplies medical kits to the front line to treat injuries as they happen. These U.S. military grade kits provide life saving measures each soldier can perform themselves, until medical help arrives, and is proven to be effective in saving lives. It was with AWHF that I learned more about the needs on the front lines and back when the soldiers come home. Since the Velvet Revolution the focus is finally moving in the right direction – jobs for the disabled wounded, equipment to protect lives on the front lines. But back then I heard of despair and disappointment in the country that they served. They call them heroes, but would not give them a job. More work needs to be done in this area and the new administration has a lot on its plate to remedy some of the wrongs that have been done to these heroes post return. After this visit with the wounded, I firmly decided that I wanted to go to the line of contact. But I didn't just want to go to experience it for myself. I wanted to understand how I could help.

And here I was, jumping out of a military vehicle, in the no man's land where international organizations don’t dare operate. This precious, beautiful land is only protected only by the people who call it home —Armenians. No one cared to save us when Armenians fled Azerbaijan during the ethnic cleansing campaign (1988-1991) and no one cares to worry over Armenians of Artsakh under Azerbaijani threat. It's really hard to explain the complexities of the conflict to non-Armenians. They are surprised at themselves for not knowing about it. What should surprise them is not that they are not aware of it, but that it has been at a standstill for three decades and in those three decades they have not heard about it even once.

I walk toward the post and shake the post officers' hands. After a brief introduction, it is straight to business. One of the officers leads me to the post entrance and I make my way up to the structure. It is narrow and long and my guides immediately point me to the narrow slit of the cement structure of the wall facing the Azerbaijani military. He gives me binoculars and tells me that they are 400 meters away. That is when reality strikes me as clear as day - there is nothing but a cement wall that stands between me and the men ready to kill me for my ethnicity. It is just like in my house in Baku during the riots against Armenians, staring through the slit of the window shutters, watching the pure ethnic hatred beyond it waiting for an opportunity to destroy me and my people. Back then my father was holding knives for the moment they broke into our Armenian home to kill us in the dark. Now these boys are holding down the Armenian fort to protect us. The feeling was the same, surreal and intense. And I deal with it just like I did back then when I was 11 years old. I asked questions.

When we went back down the wall, the soldiers hurried to make me coffee. "They are seriously preparing coffee for me," I was thinking to myself. "I should be making them coffee!" As I sat in the outdoor seating area with benches and a table, I observed the lovingly tended grape vine and the climbing beans the soldiers planted supported by a string. Leave it up to Armenians to plant grapes, beans and make coffee under enemy fire, 400 meters away from the snipers. I drank the coffee under the grape vines 400 meters away from the enemy posts and talked to the men that make Artsakh a safe place to live and visit. I asked the officers what the posts needed. They walked me through the crowded living quarters and the kitchen room where they make the most basic food. The quarters were so small, with space only for bunks monitoring equipment. There was a Chapel room, walls of which were lined with crosses soldiers that served at the post made themselves. The officers showed me the solar panels and told me the posts could use some small solar chargers, which I was able to fundraise for with AWHF upon my return to the U.S. They also said they could use some more books, and I am working to find a way to supply the posts with more books.

After the coffee and before leaving, I gifted the soldiers my care package, which made them smile and asked them what they really wanted to tell the Armenian diaspora. A quiet soldier to my left spoke up: "What we want the diaspora to know is that we don't need anything from them. We just want them to come back and live in Armenia and Artsakh."

That comment struck me all the way to Stepanakert and then Yerevan. In Yerevan, still under the influence of this experience, making me hazy to the everyday life, I listened to the words of people around me through the filter of that soldier, defending the border in an isolated post without electricity, running water and security. I noticed how the euphoria of the Revolution took the focus off Artsakh and it was troubling, but nothing disturbed me more than the people who have no focus on anything Armenia related at all. As I was visiting a family I knew prior to my departure to the U.S., they told me of their plans to leave Armenia, despite the revolution and so much promise for this young nation. This family was not destitute, far from it, with a gorgeous apartment and money, and yet the future of their country didn't seem to faze them. They mused about their potential move to the U.S. and in the same breath scolded me, someone who wasn't even born in Armenia, a refugee, someone who spends her every waking hour working toward a safe and prosperous Homeland, for not investing in Armenia by starting an actual business there.

The disconnect was so alarming to me that I hurried myself out of that conversation hoping and reassuring myself that the Revolution created more optimists than pessimists ready to drop the country we had hoped for centuries we could build.

And then I remembered that quiet boy and every boy protecting the line of contact. They are not forgotten by me, or by the masses of like-minded Armenians inside and outside of Armenia and Artsakh. The day we forget them is the day we allow others to write our history for us. The day we forget them, we let the enemy into our home.

from spotlight Karabakh

Spotlight Karabakh

By Lusine Sargsyan

This special section is a historical overview of the disputed region of the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh Republic, NKR), one of the last unresolved conflicts in the former Soviet space.

Taking Up the Challenge of Peace

By Armine Aleksanyan

Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister of Artsakh, Armine Aleksanyan on her long journey from Martouni to Stepanakert, to London and Vienna and back to Artsakh to work in the service of a country that is not recognized by the world

The Spirit of Artsakh

By Scout Tufankjian , Maria Titizian

Photographer Scout Tufankjian has captured the essence of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh) through her photos. One year after the April War, EVN Report is proud to present these images as a reminder that all children deserve to live in peace.

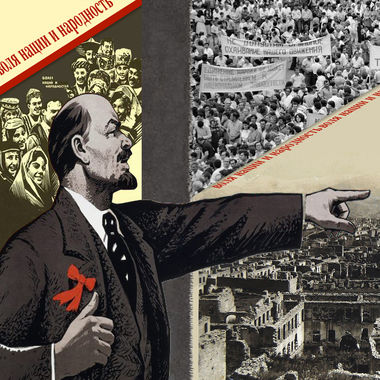

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan: Causes and Effects

By Anzhela Elibegova

An entire generation of Azerbaijanis has grown up in an atmosphere of hate against the Armenians. State-sponsored Armenophobia has penetrated all spheres of Azerbaijani society. Political Scientist Anzhela Elibegova examines the causes and effects of that policy.

Song Fragment for April Afternoon

By Eric Grigorian , Arto Vaun

Photojournalist Eric Grigorian and poet Arto Vaun collaborate in this piece that combines haunting portraits from the Four Day War last April with an evocative new poem.

From Extreme Tourism to the First Pub in Stepanakert

By Maria Titizian

Azat Adamyan, a young entrepreneur from Karabakh (Artsakh) created a hiking club, volunteered during the April War, opened the first-ever pub in Stepanakert and now has his sights set on bigger plans. While he realizes the limits of his reality, his dreams are boundless.

How It All Began: The Soviet Nationalities Policy and the Roots of the Karabakh Problem

By Mikayel Zolyan

Long before the first rallies and clashes over the territory of Nagorno Karabakh, there were several signs of the coming storm writes Mikayel Zolyan. One of these was the “war of memory,” waged not by soldiers, but in the sphere of historiography.