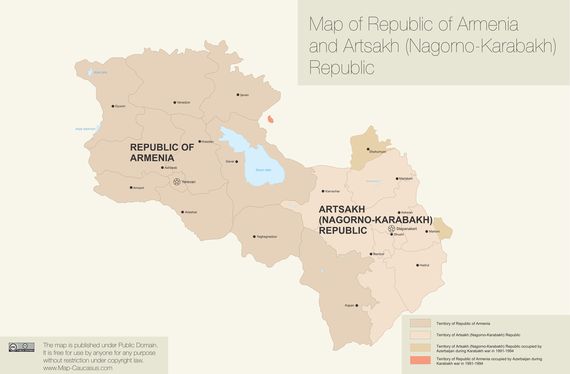

This special section provides a historical overview of the disputed region of the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh Republic, NKR), one of the last unresolved conflicts in the former Soviet space.

The Karabakh Movement, which began in 1988 as the Soviet Union was collapsing, was the expression of the will of the Armenians of Nagorno Karabakh for self-determination. It led to the Karabakh War, which lasted four years, a referendum that led to the declaration of independence in 1991; a ceasefire that brought the war to an end in 1994 and a 23-year state of no war, no peace for the people of Artsakh.

History of Nagorno Karabakh

Antiquity

Nagorno Karabakh (historical name "Artsakh") occupies the eastern and southeastern mountainous regions of Caucasus Minor and forms the northeastern part of the Armenian Highlands. It stretches from the mountains of Lake Sevan to the east of the Araks River. The name Karabakh is comprised of two words, "kara" (meaning "black" in Turkic languages or "many, rich in") and "bagh" (meaning "garden" in Persian). Thus Karabakh means "black garden" or "rich in gardens."

6th - 1st Century B.C.

The territory of modern Nagorno Karabakh is mentioned for the first time as the region of Urtekhini (Artsakh) in the inscriptions of Sardur II, King of Urartu (763–734 BC), found in the village of Tsovk in Armenia.

In the middle of the 1st century B.C., Armenia became one of the most powerful states in the Near East. Armenian King Tigran the Great, attached great significance to Artsakh and built the town of Tigranakert in Artsakh. It was one of the four towns that carried his name. Today the ruins of this town are near Agdam (in the liberated territories of Nagorno Karabakh).

1st - 5th Century

In 66-428 A.D., Artsakh was a part of the Arshakids Armenian kingdom. After its collapse, and Armenia's first division between Persia and Byzantium, Artsakh was annexed to the Albanian kingdom, situated to the north of the Kura River. In 469 the kingdom was transformed into a Persian marzpanutyun (province) retaining the name Albania.

In the beginning of the 4th century A.D., Christianity was the dominant religion in Artsakh. The creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots in the early 5th century led to the cultural development in both Armenia and Artsakh. Mesrop Mashtots founded the first Armenian school in the monastery of Amaras in Artsakh.

In 451, Armenians waged a powerful revolt, known as the Vardanants War (Battle of Avarayr) in response to Persia's policy of conversion of Armenians to Zoroastrianism. Artsakh took part in the war, during which its cavalry distinguished itself. After the Persians suppressed the Armenian's rebellion, a considerable part of Armenian forces found shelter in the unreachable fortresses and dense forests of Artsakh to continue their struggle against the foreign Persian oppression.

6th - 10th Century

Starting from the beginning of the 7th century, noble houses of Khachen and Dizak gathered strength. The Prince of Khachen, Sahl Smbatian, and the Prince of Dizak, Yesayee Abu Mousseh, spearheaded the struggle against Arabs. They, and later their successors, succeeded in making their borders unconquerable.

In the 11th and 12th centuries, Artsakh and Khachen were subjected to the invasion of nomadic Seljuk Turks, but managed to maintain their independence.

11th - 15th Century

At the end of the 12th century and during the first half of the 13th century, Artsakh flourished. Valuable architectural structures such as the Hovhannes Mkrtich (John the Baptist) Church, the portico of Gandzasar Monastery (1216-1260), Dadivank (Dadi Monastery, 1214), and Gtichavank Monastery (1241-1248) were constructed. These churches are considered masterpieces of Armenian architectural heritage.

In 1230-1240 the Tatar-Mongols conquered Transcaucasia. Due to the efforts of Prince Hasan-Jalal, Artsakh was partially saved from destruction. However, after his death in 1261, Khachen was also destroyed by Tatar-Mongols. The situation deteriorated in the 14th century during the Turkic rule of Kara-Koyunlu and Agh-Koyunlu tribes, which replaced the Tatar-Mongols. In that period many monuments and architectural wonders were destroyed. This is the time period, when the area becomes known as Karabakh.

16th - 20th Century

In the 16th century, a number of administrative-political entities called meliqdoms (principalities) were formed in Karabakh. The rulers of those principalities were called Meliqs. Further principalities were united into five larger ones: Varand, Khachen, Dizaq, Jaraberd, and Gyulistan and became known as "Meliqutyuns of Khamsa" (Arabic word for five). In the 16-17th centuries, Artsakh Meliqs spearheaded the liberation struggle of the Armenians against the Shah of Persia and the Sultan of Turkey. Along with the armed struggle, the Meliqs of Artsakh sent representatives to Europe and Russia asking for help from the Christian West.

In the middle of the 18th century, Panakh, one of the leaders of a Turkic tribe took advantage of the feudal struggle among the Meliqs of Karabakh and found shelter in the Shushi fortress with the assistance of Varanda Melik Shahnazar II. He proclaimed Karabakh to be a khanate (a political entity ruled by a Khan) and himself - a khan. The Persian Court supported this move, and the rights of local Meliqs were restricted. Penetration of Artsakh by foreign ethnic elements began, which later led to the change of its ethnic composition.

In the late 18th - early 19th century, the Russian Empire began to play a more active role in the region. Following the Russian-Persian War of 1804-1813, Persia forever surrendered most of the Caucasus to Russia, including Karabakh. The Treaty of Gulistan was signed on October 12, 1813, in the Artsakh fortress of Gulistan; the signatories were Nikolai Fyodorovitch Rtischev (Russia) and Mirza Abolhassan Khan Ilchi (Persia). However, this political status lasted only until the overthrow of the Russian monarchy during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and a local government was created in Karabakh.

The collapse of the Russian Empire paved the way for Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia to form the Republics of Transcaucasia. It is at this juncture that the modern Nagorno-Karabakh conflict arose.

In the beginning of the 4th century A.D., Christianity was the dominant religion in Artsakh. The creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashtots in the early 5th century, led to the cultural development in both Armenia and Artsakh.

“ At the end of the 12th century and during the first half of the 13th century, Artsakh flourished. Structures such as the Hovhannes Mkrtich Church, the portico of Gandzasar Monastery, Dadivank, and Gtichavank Monastery were constructed. These churches are considered masterpieces of Armenian architecture. ”

In the 16-17th centuries, Artsakh Meliqs spearheaded the liberation struggle of the Armenians against the Shah of Persia and the Sultan of Turkey. Along with the armed struggle, the Meliqs of Artsakh sent representatives to Europe and Russia asking for help from the Christian West.

On 28 May, 1918, the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic and the Republic of Armenia declared independence. On September 15, 1918, Turkish armed forces entered Baku. Massacres of the Armenians in the city left 30,000 dead.

Soviet Era

The years of 1918-1920 proved to be some of the most difficult in the history of Nagorno Karabakh, as the ancient Armenian region became the subject of territorial disputes.

On May 26, 1918, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (comprising of Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan) was dissolved. On the same day, Georgia declared its independence. On May 28, the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic and the Republic of Armenia also declared independence.

Until the end of May 1918, Nagorno Karabakh was part of the Elizavetpol Guberniya (Province). Under these circumstances, the government of Azerbaijan declared the inclusion of Baku and Elizavetpol provinces into the newly formed Azerbaijani Democratic Republic.

This was an attempt by Azerbaijan to incorporate Karabakh and Zangezur, historic Armenian areas with predominantly Armenian populations, into their own territory. However, the people of Nagorno Karabakh and Zangezur refused to acknowledge the Azerbaijani Republic's jurisdiction over their territories.

The Azerbaijani Republic tried to seize Nagorno Karabakh with the help of Turkish forces. On September 15, 1918, Turkish armed forces entered Baku. Massacres of the Armenians in the city left 30,000 dead, and hundreds of villages in the Baku and Elizavetpol Provinces were destroyed. Under these circumstances, the Headquarters of Turkish armed forces kept demanding the acceptance of Azerbaijani rule over Nagorno Karabakh. Despite the threats, Karabakh Armenians strongly refused to accept Azerbaijani rule.

On October 31, 1918 Turkey acknowledged its defeat in WWI. Its troops abandoned the Transcaucasus and were replaced by the British in December. This time the government of Azerbaijan tried to seize Nagorno Karabakh with the aid of the British. But even this time Karabakh Armenians decisively protested against the appointment of the General-Governor of Nagorno Karabakh, Khosrov bey Sultanov, whose mission was to make Nagorno Karabakh part of Azerbaijan by altering its ethnic composition.

March 23, 1920, marked the most tragic day of fighting when Turkish-Azerbaijani forces burned down Shushi, the capital of Nagorno Karabakh. Twenty thousand Armenians lost their lives on that day.

During the evening of March 22, 1920, Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh revolted. March 23, 1920, marked the most tragic day of fighting when Turkish-Azerbaijani forces burned down Shushi, the capital of Nagorno Karabakh. Twenty thousand Armenians lost their lives on that day. During the fighting, dozens of churches and historic monuments were destroyed. Soon thereafter, military units arrived from Armenia to assist the rebels and Nagorno Karabakh was completely liberated. Thereby, during the emergence of the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic in 1918-1920, it did not have any sovereignty over Nagorno Karabakh.

On April 23, 1920, Karabakh Armenians proclaimed Nagorno Karabakh an inseparable part of Armenia.

Soviet Rule

The establishment of Soviet rule in the Transcaucasus led to a new political order. After the proclamation of Soviet Azerbaijan in 1920, an agreement between Soviet Russia and the Republic of Armenia, allowed the Russian army to temporarily take control of Nagorno Karabakh until a peaceful settlement to the conflict could be agreed upon.

Immediately after the establishment of Soviet rule in Armenia, the Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan declared the “disputed territories,” namely Nagorno Karabakh, Zangezur, and Nakhichevan as inseparable parts of Armenia.

The authorities of Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic systematically violated the rights and interests of the Armenian population of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast during the entire period of its existence under Azerbaijani rule.

Based on the withdrawal of Azerbaijan's claims on the “disputed territories” and the agreement between the Governments of Armenia and Azerbaijan, Armenia declared Nagorno Karabakh an inseparable part of its territory in June 1921.

However, the Bolshevik leadership of Russia soon changed its attitude on the problem of the “disputed territories.” This political move was undertaken in consideration of the policy of assisting the “worldwide communist revolution,” in which Turkey, having ethnic links with Azerbaijan, was entrusted the role of “beacon of revolution in the East” by the Soviet Union.

Following Moscow's orders, the Azerbaijani leadership renewed its claims on Nagorno Karabakh. The Russian Communist Party adopted a decision on July 5, 1921 to separate Nagorno Karabakh from Armenia and join it to Soviet Azerbaijan, promising to establish national autonomy on its Armenian-populated territories that would stretch from Gulistan to the district of Zangezur. However, Azerbaijan delayed granting autonomy to Nagorno Karabakh.

After a two-year armed struggle and at the Russian Communist Party's insistence, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, granted a small part of Karabakh the right to an autonomous oblast on July 7, 1923. This became known as the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO). Even with this autonomous region, Nagorno Karabakh was further divided, as the other parts not included in the oblast were incorporated into the regions of Soviet Azerbaijan, thus enabling physical and geographical separation of the Armenian populated areas from Armenia.

A large portion of Nagorno Karabakh, recognized as “disputed,” was directly annexed to Azerbaijan, with the bulk of territory left out of the autonomous oblast. The authorities of Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic (AzSSR) systematically violated the rights and interests of the Armenian population of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast during the entire period of its existence under Azerbaijani rule.

Azerbaijan's policy of discrimination against Nagorno Karabakh was aimed at artificial suppression of its socioeconomic development and active de-Armenianization. Armenian monuments and cultural heritage were destroyed or presented as having Azerbaijani origin. Because of this discrimination, the Armenian population never abandoned its intent to separate from Azerbaijan.

Their struggle against the Azerbaijanis took different forms despite Azerbaijan's efforts to crush it. As early as the 1920s, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan was forced to discuss issues pertaining to the Karabakh movement. Many leaders of NKAO and its regions were accused of nationalism and were punished in the 1920-1930s; some communist party organizations were disbanded in Nagorno Karabakh.

A number of attempts by Armenians were made to raise the Nagorno Karabakh issue before the central authorities of the USSR after WWII (in 1945, 1965, 1967, 1977). Despite the fact that high-ranking officials acknowledged the problem, a solution was deferred indefinitely. Azerbaijan continued its policy of discrimination against Nagorno Karabakh by artificially suppressing its socioeconomic development and pushing an agenda of active de-Armenianization.

A number of attempts by Armenians were made to raise the Nagorno Karabakh issue before the central authorities of the USSR after WWII. Representatives of the people of Nagorno Karabakh appealed to Moscow with numerous letters and petitions (in 1945, 1965, 1967, 1977).

In 1965, 45,000 people signed a petition. Based on this petition, the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) ordered the CCCPs of Armenia and Azerbaijan to jointly investigate the Nagorno Karabakh problem. Nevertheless, Azerbaijan once again sidestepped a possible resolution to the problem by finding support among influential leaders in the USSR.

Numerous suggestions regarding the Nagorno Karabakh issue were made during the discussions about the new USSR Constitution in 1977. Despite the fact that high-ranking officials acknowledged the problem, a solution was deferred indefinitely.

Karabakh Movement

When Mikhail Gorbachev, the last General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) declared his program of glasnost and perestroika, it laid the groundwork for the liberalization of the political regime in the USSR. It was perceived as a chance to correct the mistakes of the past and eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It was at this time that the people of Nagorno Karabakh had new hopes for a democratic solution to the problem.

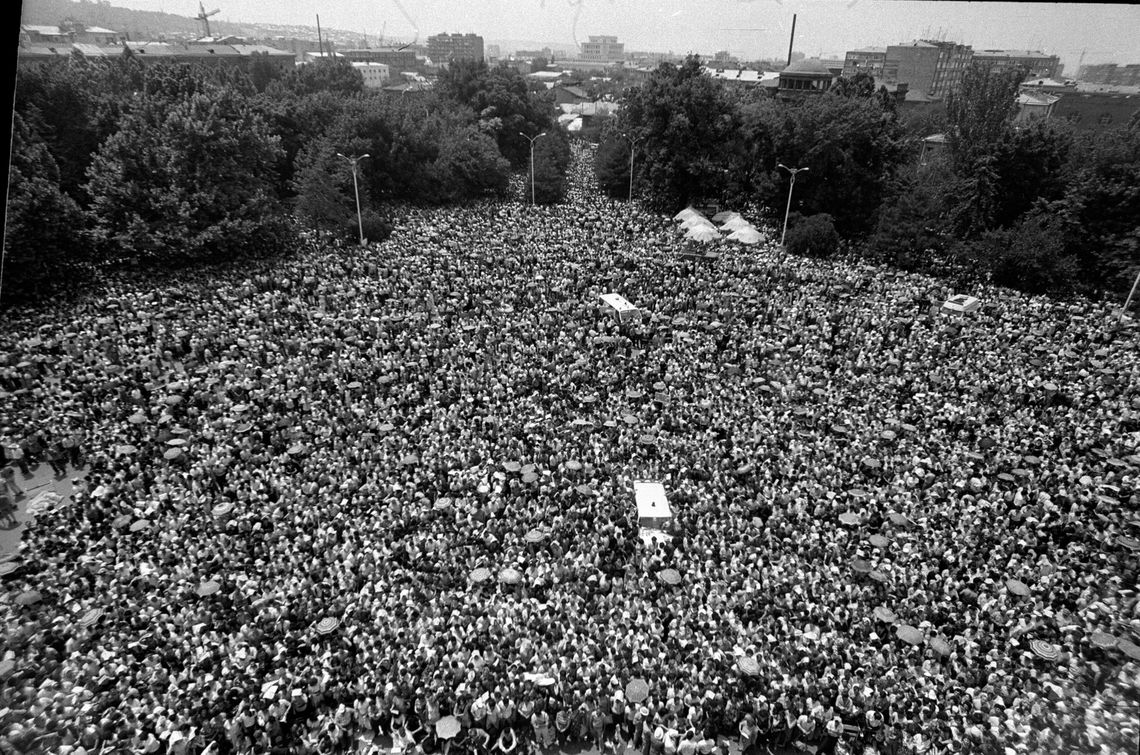

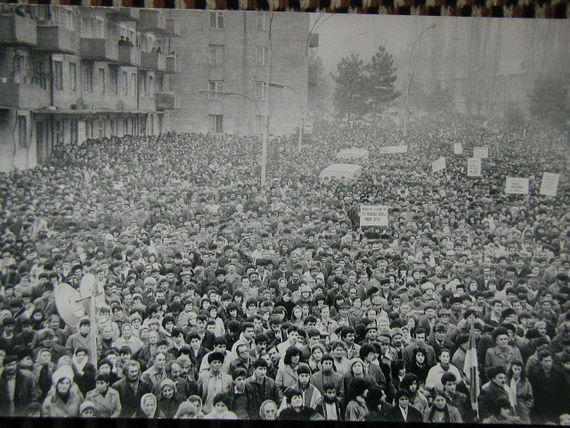

The national-liberation struggle of the people of Karabakh began at the beginning of 1988, when tens of thousands took to the streets of Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno Karabakh and signed a petition demanding the reunification of NKAO with Armenia. Representatives from the autonomous oblast were sent to Moscow to meet with government bodies to plead their case.

On February 20, 1988, the People’s Deputies made a decision at an extraordinary session of the (Soviet) Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Republic Council to appeal to the Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan SSR for secession, to the Supreme Soviet of Armenian SSR for unification, and to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR to approve this act based upon the existing legal norms and the precedence of resolving similar disputes in the USSR. With the votes 110 to 17, the resolution was passed.

Though the decision was in full accordance with the USSR Constitution, Moscow decided to reject Karabakh's demands for reunification with Armenia. This decision brought out tens of thousands of demonstrators, both in Stepanakert and in Yerevan.

On February 22, a crowd numbering thousands of people, started to move towards Stepanakert from the neighboring Azerbaijani region of Agdam “to restore order.”

Mass murders of Armenians on February 27-29, 1988 in Sumgait continued the official policy of Azerbaijan to impede the possibility of a fair solution to the Karabakh problem.

Sumgait Pogrom - 1988

Beginning on February 27, 1988, during the early stages of the Karabakh Movement, a pogrom lasting three days against the Armenian population took place in the city of Sumgait in Soviet Azerbaijan. At the time, approximately 18,000 Armenians were living in Sumgait.

Mobs of ethnic Azerbaijanis targeted, attacked and killed Armenians in their homes and on the streets of the city. One day later, on February 28, a small contingent of troops from the Ministry of Internal Affairs attempted to put an end to the widespread rioting without success. It was only after the government imposed a state of martial law that the massacre was put to an end.

Official figures released at the time by the Prosecutor General of the USSR put the number of dead at 32, although unofficial reports place the figures much higher.

Baku Pogrom - 1990

Starting on January 12, 1990, a week-long pogrom against Armenians broke out in Baku, Soviet Azerbaijan. Armenian civilians were beaten, burned alive, tortured, murdered and expelled from the city. There were verified reports that the attacks were not spontaneous as those responsible had lists of Armenian residents. At the time, approximately 200,000 Armenians were living in Baku. Depending on the source, the number of killed range from 68-90.

The activity of Azerbaijani authorities intensified, along with their policy of suppression, ethnic cleansing, and terror. Active members of the Karabakh Movement were persecuted at increasing rates and arrested under the false pretense of real “criminal cases.”

Maragha Massacre - 1992

The Maragha massacre took place on April 10, 1992. Armenian villagers, including women, children and the elderly were killed, their homes ransacked and burnt. The village of Maragha was destroyed and later occupied by Azerbaijani forces. It is estimated that over 50 Armenians were killed, with another 53 taken hostage, 19 of whom never returned.

“ Beginning on February 27, 1988, a pogrom lasting three days against the Armenian population took place in the city of Sumgait in Soviet Azerbaijan. At the time, approximately 18,000 Armenians were living in Sumgait. ”

The USSR interior forces with the Azerbaijani OMON continued their punitive operations. It was evident that a large-scale war was brewing.

Karabakh War

1991

From the beginning of 1991, Azerbaijani military forces attacked the Armenian populations of both the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) and the Shahumyan region. On January 2, Azerbaijani television broadcast the president of Azerbaijan, Ayaz Mutalibov’s edict on the introduction of a presidential government in NKAO and the adjacent Azerbaijani regions.

On January 14, the Azerbaijani Supreme Soviet Presidium made a decision to unify two neighboring regions, the Armenian-populated Shahumyan and Azerbaijani-populated Kasum-Ismailov, into one region named Goranboy. The aim of the Azerbaijani leadership was obvious: to deport the indigenous inhabitants of Shahumyan (82% Armenians) and repopulate the Armenian village with Azerbaijanis.

The situation in Nagorno Karabakh and adjacent Armenian regions became seriously aggravated. Operation Ring was one event in particular that caused severe deterioration in the region. This punitive act against the Armenians in late April and early May of 1991 involved forces of the USSR Ministry of the Interior and the Azerbaijani OMON (Special Purpose Mobility Unit or special police unit). On the pretext of passport "checks," an unprecedented action of state terror was carried out with the aim of destroying the center of the Karabakh Movement and undermining national unity. During three days, the population of 24 villages in Karabakh were forcibly displaced. As a result of these actions, more than one hundred people were killed and several hundreds were taken as hostages.

On May 4, the President of Armenia, Levon Ter-Petrosyan met with Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, the President of Russia. No statement was issued following the meeting. The USSR interior forces with the Azerbaijani OMON continued their punitive operations. It was evident that a large-scale war was brewing.

As a result of the critical situation in Nagorno Karabakh, the Executive Committee of the Regional Soviet (Council) declared a state of emergency in the region. On the same day, the Executive Committee appealed to the UN and to other leaders of a number of states to save the Armenian people from physical extermination by granting them political asylum.

On June 24, the NKAO delegation left for Moscow to meet with the Soviet leadership to discuss the issue of restoration of the regional bodies of power and possible dialogue with Azerbaijani authorities on the peaceful settlement of the Nagorno Karabakh situation. The NKAO delegation had a meeting with the Supreme Soviet Chairman, A. Lukyanov, USSR Defense Ministry D. Yazov, and Internal Affairs Minister B. Pugou. Regardless of their promises, all talks yielded little in terms of practical results.

Meanwhile, the Azerbaijani leadership continued its policy of Armenian deportations under the false guise of “voluntary departures.” These actions were accompanied with such atrocities as torture, murder, looting, banditry, brutality, and extreme violence.

On September 2, a Joint Session of the Nagorno Karabakh Regional Council and the Council of the Shahumyan Region was held. In light of the wishes of all peoples residing within the boundaries of Nagorno Karabakh and the Shahumyan Region, the Republic of Nagorno Karabakh was proclaimed. This was almost immediately followed by Azerbaijani retaliation as Stepanakert was bombarded.

The most important turn of events in the national liberation struggle of the Karabakh people was the referendum, held on December 10, 1991. 98 percent of the participants of the referendum voted for the independence of Nagorno Karabakh. On December 28, despite constant bombardment by the Azerbaijani Army, parliamentary elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Republic were held in Karabakh. On January 6, 1992, the newly elected legislative body of Karabakh adopted the Declaration of Independence and appealed to all the countries of the world to recognize the Nagorno Karabakh Republic (NKR) and help prevent the genocide of the Artsakh Armenians.

1992

The beginning of 1992 was marked by Azerbaijani incursions into the territory of Agdam and the attack on the Armenian village of Khramort, which was subsequently burnt to the ground. The NKR capital and various Armenian villages were under constant intensive shelling. On January 31, Azerbaijan began an offensive along the entire front line.

The escalating military operations compelled NKR to organize its own defense. Voluntary groups of freedom fighters were established throughout Artsakh. Headquarters of these self-defense forces were established to coordinate the military operations. This paved the way for the creation of a regular army.

One of the primary tasks of the Artsakh self-defense forces was the removal and destruction of the enemy's bridgehead at Khojaly, an area where considerable manpower and military equipment existed. To ensure efficient communication within Karabakh, it was necessary to re-open a corridor linking the area of Askeran with Stepanakert, and regain control of the airport, which was in Azerbaijani hands.

On February 25, the Artsakh self-defense forces, taking up positions in western Khojaly, demanded that the Azerbaijanis leave the military base and allow civilians through the established humanitarian corridor.

In the beging of March, the Azerbaijani Army undertook a wide-scale offensive that involved the entire front line. The main blow was aimed at the Martakert, Askeran, and Martuni districts. Even with the liquidation of the Khojaly military base, the shelling did not subside. The Azerbaijanis positioned in the town of Shushi and started bombarding the NKR capital and other populated areas. On April 10, the Maragha massacre took place.

In the morning of May 8, the Artsakh self-defense subunits started a counteroffensive operation and took the Shushi-Lachin road under their control. As a result of fierce street battles, Armenian troops occupied the central quarters of the town by evening.

On May 9, Shushi was liberated entirely. After destroying the firing points in Shushi, the self-defense forces’ next mission was to open the important road of Shushi-Lachin-Zabukh, remove the blockade, and restore normal daily activity in the republic.

On May 18, the Karabakh Army entered Lachin (Kashatagh), thus ending the three-year blockade. After the Shushi-Lachin operation, the tension in the conflict area was reduced considerably.

In the first days of June, the Azerbaijani Army, expanding its offensive in several directions, occupied the regional center of Martakert and a number of villages in the region. A large threat hung over Artsakh as 40 percent of the territory was officially occupied by Azerbaijani troops. Meanwhile, heavy battles continued in different areas of the front. The Azerbaijani air force continued attacking civilian targets.

On August 18, pellet bombs were dropped on Stepanakert even though the use of such weapons was forbidden by international law. The following days, the villages of the Martuni, Martakert, and Askeran districts were bombarded.

During the last days of October, Azerbaijani troops made two attempts to cut off the Lachin humanitarian corridor, but were stopped 12 kilometers away and were pushed back. On October 19, Karabakh forces started a counteroffensive operation in the southern part of the corridor and proceeded until they reached the borders of the Kubatly district.

The end of 1992 was marked by the abatement of hostilities along the entire length of the front.

1993

Early in January, 1993, military offensives along the length of the Azerbaijani-Karabakh front reignited. Azerbaijan engaged almost its entire arsenal — attacking with aircraft, heavy tanks, various weapons, and infantry.

In early February, heavy fighting began at the northern front. The NKR Self-defense Army undertook a counter offensive operation in the Martakert district, in the hopes of liberating the occupied territory. By late February, Karabakh forces succeeded in re-establishing full control of the Martakert-Kelbajar road and of the Sarsang Reservoir where a vital electrical power station was located.

The relatively quiet situation in April abruptly changed late in spring. The Azerbaijani Army resumed military operations along the entire length of the front, concentrating forces at the eastern, Martuni area. All attempts to break through the defenses of Karabakh troops failed.

On July 4, the Azerbaijani Army began a large-scale offensive operation in the Askeran, Hadrut, and Martakert regions supported by airpower and armored tanks. In all regions, Azerbaijani troops were repelled and retreated. Shelly, a village that was used by the Azerbaijanis to mount artillery shelling onto Askeran and Stepanakert, finally came under the control of Karabakh forces.

To ensure the safety of Stepanakert, the Artsakh armed forces moved to liquidate the military base of Agdam. On July 23, Karabakh forces broke down the enemy resistance and entered Agdam. This removed the threat of systematic shelling of Stepanakert and the threat of further offensives on Askeran and contiguous districts. With the loss of their large military base, the Azerbaijani leadership was compelled to propose a cease-fire. On July 25, for the first time during the conflict, an arrangement for a three-day ceasefire was achieved.

However, the situation rapidly changed in August. Sustained attacks on Karabakh resumed and were concentrated from the direction of Jebrail. Due to the actions of the self-defense forces, a number of Azerbaijani military bases were destroyed. During the following days, the military units of the NKR Defense Army liberated the Hadrut district and took the territory of Jebrail under their control.

On August 3, an agreement on a 10-day ceasefire was signed between Azerbaijan and NKR. An arrangement for a meeting between the leaders of Azerbaijan and Nagorno Karabakh was scheduled for September 10. However, the agreement did not effectively transfer the resolution of the military conflict into a political one. The relative quiet along the front lasted merely a month and a half.

On the night of the October 10, Azerbaijan resumed military operations in the Hadrut region of the front. On October 21, units from the Azerbaijani Army began an attack towards the Hadrut-Jebrail direction, capturing a number of strategic hills and once again threatening the population of the Hadrut region. On October 24, the NKR Army counter-attacked, neutralizing a number of Azerbaijani firing points, including the Horadis military base.

During November and December, clashes continued between Azerbaijani troops and NKR armed forces. By the end of 1993, the territory stretching from the railway junction of Horadis to the state border of Armenia was under the control of Karabakh forces.

The leadership of Azerbaijan, realizing that the mobilization of their own troops was not sufficient, began employing mercenaries.

1994

Once again Azerbaijan attempted to gain control of the situation by intensifying attacks on the entire front-line. Heavy fighting was waged from the Omar Pass to the Araks River. Despite serious losses, Azerbaijani troops did not retreat. On February 18, the northern sector, including the Omar Pass, was entirely controlled by the Karabakh Army, thus they came to control the entire Kelbajar district.

In late February and early March, fighting developed along the southeastern border of the front. Backed by armored forces, artillery, and aircraft, Azerbaijani troops attempted to break through the Karabakh defense and advance to Fizuli. However, the Karabakh forces strongly defended their positions.

On April 10, as a result of counter offensives in the northern-eastern front, the NKR armed forces took a number of strategic hills in the Gulistan-Talish region. In the middle of April, the NKR Defense Army liberated the Armenian villages of Talish, Chily, Madagis, and Levonarkh. Karabakh troops were also successful in their southern movement and managed to take control of the main road in Agdam-Barda.

These decisive military defeats compelled Azerbaijan to accept the Russian Federation's proposal on a peace agreement. On May 5, in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, under the mediation of Russia, Kyrgyzstan, and the CIS Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, Azerbaijan, Nagorno Karabakh, and Armenia signed the Bishkek Protocol.

On May 16, the Defense Minister of Armenia, Serzh Sargsyan, Defense Minister of Azerbaijan, Mammadrafi Mammadov, and the NKR Defense Army Commander, Samvel Babayan, held a meeting in Moscow and signed a ceasefire agreement, which entered into force on May 17, 1994.

The agreement has no expiration date and remains in force until a final peaceful settlement to the conflict is reached.

Peace Process

Since 1992, the main vehicle for the resolution of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict has been the Minsk Group of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which has sought to mediate a durable peace settlement. The Minsk Group, currently co-chaired by the United States, Russia and France, has come forward with a series of proposals to solve the crisis.

During 1992-1997, NKR participated directly in the OSCE peace talks. It is a signatory to the May 1994 tripartite ceasefire agreement. Subsequently, Azerbaijan rejected NKR as a negotiating partner and it was removed from the negotiation process. Authorities in NKR have said repeatedly that the conflict cannot be resolved without the concurrence of NK.

The ceasefire regime over the past 23 years has been constantly violated, with both sides exchanging fire resulting in loss of military and civilian lives and non-military property damage to border villages. The violations have not been isolated to the Line of Contact but have also spread to the state border between Armenia proper and Azerbaijan with border villages coming under attack, including civilian targets (schools, homes, community centers).

Despite repeated calls by the OSCE Minsk Group for a halt in hostilities, escalating tensions eventually led to the April War. There have been documented cases of the Azerbaijani military committing war crimes against both military servicemen and villagers over the course of the 22-year-long ceasefire.

On February 20, 2017, a national referendum on a new draft Constitution was held in the Nagorno Karabakh Republic. Voter turnout was 76.44 per cent of registered voters, of which 87.6 per cent supported the adoption of the new Constitution, which will see Karabakh transition from a Parliamentary to a Presidential system.

Around 100 international observers from 30 countries monitored the voting process and positively assessed the organization and conduct of the referendum noting their transparency and compliance with international standards.

A key innovation was the increase of direct participation of citizens in public affairs by providing them with the right to legislative initiative, as well as on proposing amendments to the Constitution.

The package of reforms also envisioned changing of the name of the republic; thereby the Nagorno Karabakh Republic will now officially be called the Republic of Artsakh.

The following sources were used in the preparation of this section:

http://www.nkrusa.org/nk_conflict/index.shtml

http://armeniarising.blogspot.am/search?updated-max=2016-07-28T17:44:00%2B04:00&max-results=7

http://www.president.am/en/karabakh-nkr/

http://www.nkr.am/en/the-war-of-19911994/83/

http://armenian.usc.edu/focus-on-karabakh/research/origins-geographic-term-karabakh/

Photo credit: Photolure and englishar.wordpress.com

Four Day War

In the early morning hours of April 2, 2016, Azerbaijani Armed Forces launched a large scale military offensive along the entire length of the 170-kilometer Karabakh-Azerbaijan Line of Contact. This upsurge of violence, the worst since the 1994 ceasefire agreement that brought an end to the Karabakh War, has come to be known as the Four Day or April War.

The authorities of Armenia and Artsakh informed the international community about the unprecedented aggression escalated by Azerbaijan and called on the OSCE Minsk Group to show targeted reaction to the situation and settle the Nagorno Karabakh conflict.

International institutions, humanitarian organizations, and the three co-chairs of OSCE Minsk Group (United States, Russia, and France) condemned the use of force in the conflict zone, calling on the parties to cease all military operations and stabilize the situation on the Line of Contact.

This military offensive and unprecedented aggression by the Azerbaijani side, which was met by counter-operations by the Nagorno Karabakh Defense Army spiraled out of control, resulting in hundreds of casualties and wounded on both sides, including civilians.

War crimes committed by the Azerbaijani side are violations of International Humanitarian Law and the Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War and the Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions (August 12, 1949) relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts by the Azerbaijani Armed Forces during the Nagorno Karabakh April War (2016).

A number of cases of war crimes are currently at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) awaiting a final decision. Among those cases are the beheadings of Armenian servicemen Kyaram Soloyan, Hrand Gharibyan and Hayk Toroyan; documented reports of torture and mutilation on 18 bodies of Armenian servicemen; the murder and mutilation of the Khalapyan family of Talish, NKR.