Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

A year after the outbreak of the 2020 Artsakh War, heated debates are still occurring in Armenia’s analytical and political circles on the causes of the war. Multiple claims are made during these lively discussions, but they rarely contain systematic and comprehensive explanations of the structural conditions and circumstances behind Azerbaijan’s large-scale offensive in September 2020.

The vast majority of Armenian politicians and analysts who express views on this topic focus on singular factors (depending on their political affiliation or professional preferences), ignoring multiple other causal explanations of the 44-day war. This trend makes it hard to see the bigger picture. That is why a comprehensive analytical framework is needed for the study of the entirety of variables that contributed to the outbreak of hostilities in the conflict zone last autumn.

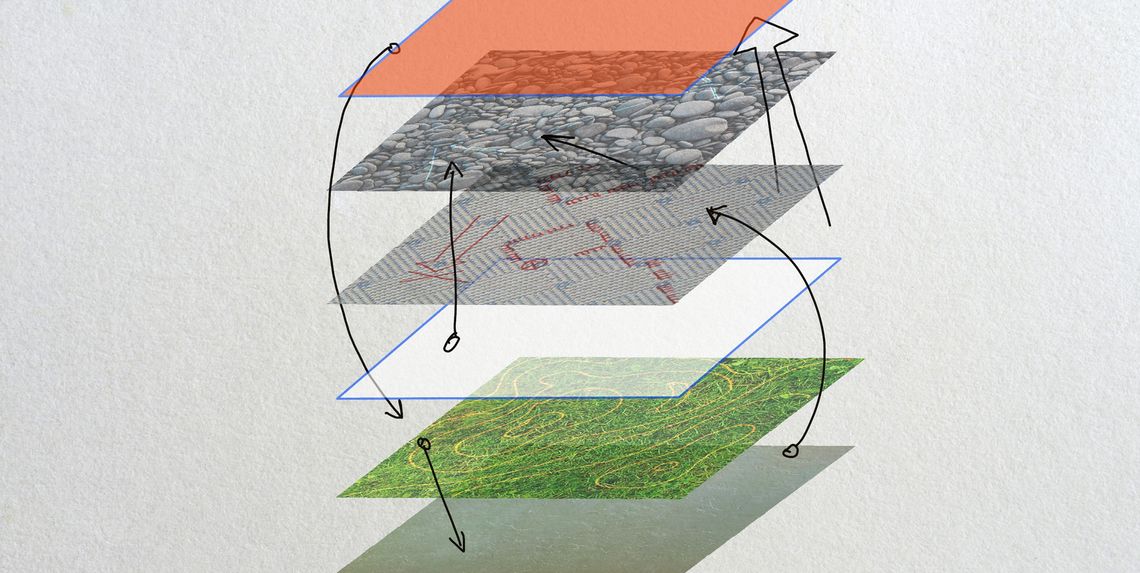

One of the most popular tools for the study of causes of wars is an analytical framework known as “levels-of-analysis.”[1] This analytical framework is used by Jack S. Levy and William R. Thompson in a book entitled “Causes of War.” Levy and Thompson identify three main levels at which different theories emphasize sources of war causation—the system (international system), state and societal, and decision-making levels. They also add the “dyadic” level, which displays the bilateral dynamics between pairs of states.

In their book, Levy and Thompson present the theories that explain causes of wars at the aforementioned levels of analysis. At the system level, the authors group together all the theories, which emphasize the changes in the international system as the main drivers of war. At this level, such factors as the number of great powers in the system, economic and military balance between them, the nature of international norms, as well as the structure and significance of international institutions in the system, are studied.

At the dyadic level, Levy and Thompson focus on the following theories of war causation: the theory of international rivalries, the “steps-to-war” model, the bargaining theory of war, and theories of economic interdependence and peace.

From all of these theories, the “steps-to-war” model is most useful for the Karabakh context. Paul D. Senese and John A. Vasquez are the authors of this model. It shows that there is a certain sequence of developments and emerging factors, which significantly increases the probability of war between conflicting states. The first of these factors is the nature of conflicts. Senese and Vasquez argue that territorial disputes are more likely to turn into full-blown wars. Formation of alliances is another step that raises the probability of war between conflicting parties. If the conflict occurs between two states with a previous history of military clashes, the probability of war is even higher. Military build-ups and arms races are also an important driver of escalation. Senese and Vasquez conclude: “The impact of each step on the probability of war is cumulative, so that the combination of two or more steps makes the relationship even more war-prone.”

Theories at the state and societal level focus on the impact of domestic processes on foreign policy decisions. From the theories of war causation mentioned by Levy and Thompson at this level, the most relevant ones for our context are the diversionary theory of war and the theory of democratization and war.

According to the diversionary theory of war, ruling elites frequently conduct aggressive foreign policies to divert the attention of the domestic public from socio-economic and political problems inside the country, trying to achieve a “rally around the flag” effect.

The essence of the democratization and war theory is the assumption that democratizing countries with weak institutions are more war-prone than other regime types. In the absence of strong institutions, political systems are incapable of channeling the demands from newly-emerging social groups in the political process. This creates incentives for political elites to utilize nationalist and populist rhetoric for attracting mass support.

The last level of analysis singled out by Levy and Thompson is the decision-making level. At this level, the emphasis is put both on the personal characteristics of decision-makers and the peculiarities of decision-making processes in various government bodies.

Any comprehensive study of the causes of the 2020 Artsakh War must include all the sources of causation at the above-mentioned levels. Only the juxtaposition of causal factors at different levels of analysis can provide a holistic overview of conditions and developments that made the 2020 war possible.

The main factor at the system level was the weakening of the unipolar order and its gradual transition to multipolarity. This process caused the decline of the liberal order, which was in direct dependence on unipolarity and the relative power of the hegemonic state in the system—the United States. The emerging multipolar order and the relative decline of the hegemonic power in the system convinced the decision-makers in Washington, D.C. to conduct more pragmatic foreign policy and mobilize their resources toward the containment of their main global challenger—China. This global trend has resulted in a growing U.S. disengagement from the South Caucasus over the last 10 years, which significantly changed the post-Cold War balance of power in the region. The Trump presidency became the pinnacle of this process.

The U.S. engagement in the mediation of the Karabakh conflict peaked in 1999-2001, when Washington was the leading and the most active co-chair of the OSCE Minsk Group, nearly brokering a peace agreement in Key West. The U.S. and France were also actively engaged in the formulation process of the Basic Principles (also known as the Madrid Principles) presented to the conflicting parties in 2007. However, from that point on, Russia has been the only mediator state putting peace plans on the table from time to time. A vivid indication of the U.S. disengagement from the Karabakh peace process is the fact that the current U.S. co-chair of the Minsk Group, Andrew Schofer, who was appointed to that position in 2017, doesn’t hold an ambassadorial rank.

These tectonic changes at the system level had a tangible effect on our region. The gradual transition from unipolarity to multipolarity has significantly increased the weight and autonomy of regional powers—Russia and Turkey in this case. Ankara’s foreign policy in its near neighborhood became bolder and more adventurous. Turkey’s unequivocal support to Azerbaijan on the eve of the 44-day war was crucial in Ilham Aliyev’s decision to launch the offensive.

With the decline of the liberal order, the role of norms in the international system has also decreased throughout the years. Without the active engagement of the system’s hegemonic power, the principles underlying the liberal order gradually lost their influence and popularity. In the Karabakh context, the most important of these principles were non-use of force and peaceful resolution of conflicts through negotiated settlements and third-party mediation.

All the processes that were taking place at the dyadic level in the Karabakh context corresponded to the “steps-to-war” model of Senese and Vasquez: a territorial dispute was at the basis of the conflict, the conflicting parties had an experience of military clashes before the 2020 war, they also formed military alliances with regional powers and were engaged in an arms race. The combination of these factors significantly increased the probability of war.

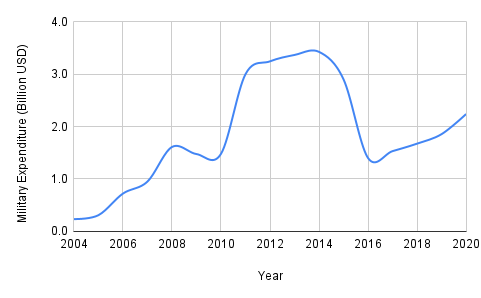

The arms race factor is of special importance in the Karabakh context, as it shifted the military balance in the Armenia-Azerbaijan dyad in the latter’s favor. This is clearly seen when we compare Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s military spending over the years. Azerbaijan’s military expenditure from 2004 to 2020 is presented in the table below.

Armenia’s military budget fluctuated between $52 million and $92 million from 1995 to 2004. It then skyrocketed to $142 million in 2005 as a reaction to Azerbaijan’s increased military spending. The next big spike took place in 2008, when the budget reached $400 million. After that, Armenia’s military spending plateaued and remained at the level of $400-457 million for the next 10 years. In 2018, the first significant increase in a decade was registered when the military spending soared from $443 million in 2017 to $608 million in 2018. Armenia’s military spending in 2019 and 2020 was $673 million and $638 million respectively.

At the state and societal level, as already mentioned, the diversionary theory of war is useful for the study of war causation in the Karabakh context.

The main argument of this theory is applicable for the analysis of Azerbaijan’s internal dynamics. After coming to power in 2003, Ilham Aliyev has instrumentalized the Karabakh conflict and state-sponsored Armenophobia to divert the attention of Azerbaijani society away from socio-economic and political problems. The state-generated narratives and discourses about the conflict, as well as the promise to return the lost territories, became one of the main sources of legitimacy for the Aliyev regime. The Karabakh issue was the pillar of the social contract between Aliyev and Azerbaijani society. In that respect, the only alternative to the war for Aliyev was the weakening and the eventual loss of his power. This dichotomous choice became evident after the clashes at the Armenia-Azerbaijan state border in July 2020, when thousands of protesters took to the streets of Baku demanding that Aliyev start the war.

Another theory explaining war causation at the state and societal level is the theory of democratization and war. In 1995, Edward Mansfield and Jack Snyder penned their famous article “Democratization and the Danger of War.” In this paper, they studied the correlation between democratization and war, coming to the conclusion that countries undergoing transitions to democracy are more likely to experience a war than countries where no regime change is going on.

The processes described by Mansfield and Snyder took place in Armenia after the Velvet Revolution of 2018, when Nikol Pashinyan’s government started reacting to various allegations of the opposition by hardening its rhetoric on the Karabakh conflict and making numerous populist statements. In the short term, it allowed them to gain support from certain segments of society. However, in the long run, these statements that were made for domestic consumption sent a wrong signal to Azerbaijan and in a way legitimized Baku’s unconstructive actions, approximating the outbreak of the war.

An important contributing factor at the decision-making level was the unprofessionalism and incompetence of Armenia’s post-2018 government in foreign policy and security issues. The lack of in-depth knowledge in these areas was a huge barrier for Nikol Pashinyan and his team to correctly evaluate Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s military capabilities, as well as the geopolitical developments in the region. The incompetence and inefficacy of Armenia’s vast bureaucracy was an additional factor in this process.

Due to this lack of experience and expertise, some poorly-calculated decisions were also made in the interaction with Russia, which caused a mini-crisis in the bilateral relations with Moscow and emboldened Baku.

As can be seen, a unique combination of causal factors at different levels made the 44-day war possible. The timing of the attack was also chosen carefully—amid a global pandemic and on the eve of the U.S. presidential election. Armenia lacked the analytical capacity at the time to take note of all these changes and processes in the region and beyond. At this point, the scrupulous analysis of the above-mentioned sources of war causation is of crucial importance for the prevention of new national debacles in years to come.

--------------------

[1] This framework was first used by Kenneth Waltz in his seminal volume “Man, the State, and War.’’

Also see

Why Armenia Lost and Why Azerbaijan Will Also Lose: The Trappings of Strategic Narcissism

By Nerses Kopalyan

While Baku prepared for war, Armenia relied on overconfidence, willful ignorance and underestimated the enemy leading to its defeat in 2020. But Azerbaijan, intoxicated by its own victory, will also lose because of Aliyev’s strategic narcissism.

Who Is Responsible For the 2020 Defeat?

By Gaïdz Minassian

Gaidz Minassian delves into the turbulent spaces of history, memory and identity and deconstructs why the mother of all battles—the construction of a State on its sovereign pillars—was undermined.

Arms Supplies to Armenia and Azerbaijan

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

For nearly three decades, Armenia and Azerbaijan have been buying large quantities of weapons from a number of countries. Hovhannes Nazaretyan presents a comprehensive list of weapons acquired by both countries since independence.

Military Expenditures and the Economy: Behind the War of Weapons

By Ani Avetisyan

Azerbaijan increased its military spending by 17% in 2020; this was among the largest annual increases in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Ani Avetisyan breaks down the numbers of the military expenditures of both Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Russia’s Increasing Military Presence in Armenia

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

When Armenia declared independence in 1991, there was still a large contingent of Soviet troops in the country. Russian military presence, however, stretches back to the early 19th century and now, after the 2020 Artsakh War, is expanding.

Russia’s Partnership With Turkey and What It Means for Armenia

By Zaven Sargsian

Many assumed that Turkey’s direct involvement in the 2020 Artsakh War and thereby its intrusion into Russia’s “near abroad” would be met with hostility by Russia, or at least vocal condemnation. The reaction was mild, writes Zaven Sargsian.

Armenia in the Biden Era

By Artin DerSimonian

With Russia and now Turkey having new footholds in the South Caucasus following the 2020 Artsakh War, will Washington under the Biden administration attempt to counter these new developments?

Podcast featuring the author

On August 18, 2021, Armenia’s Prime Minister unveiled the Armenian Government’s 2021-2026 Programme and said that opening an era of peaceful development for Armenia and the region is their most important mission. EVN Report’s Maria Titizian speaks to political analyst Tigran Grigoryan who takes a closer look at the Programme’s vision for Artsakh, security and defense and foreign policy.