Mon Feb 15 2021 · 8 min read

Russia’s Partnership With Turkey and What It Means for Armenia

By Zaven Sargsian

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

One of the more surprising aspects of the 2020 Artsakh War was Russia’s reaction to Turkish involvement in the conflict. Many war watchers assumed that Turkey’s intrusion into Russia’s “near abroad” would be met with Russian hostility, if not at least vocal condemnation.

Yet, Russia’s reaction was mild. Contrary to most expectations, Russia took an unusually tolerant attitude toward Turkey’s obvious military involvement in favor of Azerbaijan—involvement that tipped the scales in deciding the outcome.

Are we witnessing a Russia that is less engaged in the Caucasus and more accommodating to regional actors? Likely not. Rather, what we’re witnessing is a display of the Russian-Turkish partnership.

History Repeating Itself

The Russian-Turkish partnership of today is not unlike that of a hundred years ago. In March 1918, the newly formed Russian Soviet Republic, led by the Bolsheviks, exited the First World War by signing the humiliating Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the German Empire. The treaty upset the Allied Powers, who felt betrayed by this withdrawal from the war and became convinced that the communists in Moscow needed to be overthrown.

While the Allied Powers were busy funding anti-revolutionaries in Soviet Russia, the Ottoman Empire was faring no better. Soon after the November 11, 1918 armistice, the Allied Powers took up to partitioning the defeated Ottoman Empire between Britain, France, Italy, Greece and Armenia, culminating in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres.

Thus, in the early 1920s, Soviet Russia and Turkey were allied in their mutual defense against the Allied Powers. For the First Republic of Armenia, the failure to read this new geopolitical reality proved fatal to its independence and its territorial interests in the Armenian Highland of Anatolia.

History may be repeating itself and we may again be witnessing a changing geopolitical reality that could have profound consequences for Armenia—if it hasn’t already. Over the past several years, Turkey has, in several areas, been pivoting away from the West and toward a partnership with Russia. As a result, Russia and Turkey have a closer relationship now than at any time in recent memory.

What’s Causing Turkey’s Eastern Pivot

For Turkey, the impetus of its eastern pivot has been its strained relations with the U.S., which has been a well-known fact for several years now. By April 2016, then-President Obama was publicly voicing his disappointment with Erdogan; as described by one interviewer: “early on,” Obama saw Erdogan “as the sort of moderate Muslim leader who would bridge the divide between East and West – but Obama now considers him a failure and an authoritarian, one who refuses to use his enormous army to bring stability to Syria.”

Relations between Turkey and the U.S. appear to have deteriorated dramatically by July 15, 2016, when a coup attempt was launched against Erdogan’s government. Although the coup ultimately failed, it deeply unsettled Erdogan and his supporters. Almost immediately, Erdogan accused Fethullah Gulen, a Turkish religious leader living in Pennsylvania, of having inspired the coup attempt. On July 16, 2016, Erdogan publicly called out Obama for refusing to hand over Gulen. “Dear Mr. President, I told you this before. Either arrest Fethullah Gulen or return him to Turkey. You didn’t listen. I call on you again, after there was a coup attempt. Extradite this man in Pennsylvania to Turkey! If we are strategic partners or model partners, do what is necessary.”

The Turkish Labor Minister Suleyman Soylu, a close Erdogan associate, went even further and in a TV interview blamed the U.S. for the coup, reportedly stating: “America is behind the coup.” In fact, the allegations against the U.S. became so prevalent that the U.S. Ambassador to Turkey, John Bass, had to issue a statement denying it. “Some news reports – and, unfortunately, some public figures – have speculated that the United States in some way supported the coup attempt. This is categorically untrue.”

Turkish-Russian Relations Deepen

In contrast to the accusations against the U.S., Turkey’s Foreign Affairs Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu warmly thanked Vladimir Putin for his support of Erdogan’s government during the coup attempt. “We thank the Russian authorities, particularly President Putin. We have received unconditional support from Russia, unlike other countries.”

One month later, Erdogan was in St. Petersburg for his first trip abroad after the coup attempt. The August 9, 2016 meeting was also the first time Erdogan and Putin had met since Turkey shot down a Russian jet in November 2015 near the Syrian border. At the meeting, Erdogan thanked Putin for his support, stating that Putin’s “call straight after the coup was very pleasing for me and our leadership and our people.”

The gushy exchange between the two leaders was followed by a public deepening of relations, including an agreement for the construction of a major undersea gas pipeline, and a proposal for a general ceasefire in Syria. Yet, the more significant revelation came in 2017. On June 1, 2017, during Putin’s annual media conference, in response to a question from a Turkish reporter, Putin announced that Russia had “discussed the possibility of selling S-400s [to Turkey]. We are ready for this.”

It appears that Russia was not only ready, but had already agreed with Turkey on the technical details of a contract. Turkey would pay $2.5 billion for two S-400 battery systems with 240 warheads, and search-detection-tracking and baffle radars.

It was big news. One Moscow-based think tank said the deal was “a clear sign that Turkey is disappointed in the U.S. and Europe.” American news described the deal as “signal[ing] [Turkey’s] turn away from the NATO military alliance that has anchored Turkey to the West for more than six decades.”

Amid this backdrop of a deepening relationship, Russia and Turkey also discussed Nagorno-Karabakh. Notably, in a November 2017 meeting between Erdogan and Putin in Russia, Erdogan raised the Karabakh issue with Putin and reportedly asked him to pay more attention to it. “He [Putin] thinks so himself, but in my opinion, he has no high hopes because of the positions of the parties. I reminded him of the decision taken on the liberation of the five regions and that the Armenian side was supposed to leave these territories.”

It’s unclear if Erdogan and Putin discussed Karabakh again after their November 2017 meeting, but it is certainly likely. In 2018 alone, Erdogan and Putin held seven private meetings and six open door meetings, as well as eight phone conversations.

Thus, while Turkey’s relationship with Russia deepened, its relationship with the West continued to deteriorate. Like the S-400 purchase, another low point came in October 2019, when Turkey invaded northern Syria to purportedly expel the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which Turkey considers terrorists with ties to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

The West saw this as a destabilizing act by Turkey, and a move that countered their interests. Only five days after Turkey’s invasion, every EU country decided to stop selling arms to Turkey. The same day, the U.S. declared sanctions against the Turkish ministries of defense, interior and energy. Then, on October 29, the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly voted to recognize the Armenian Genocide, which was later followed by the U.S. Senate voting unanimously on a parallel motion. The New York Times reported that the move “underscored [U.S.] lawmakers’ bipartisan rage at Turkey.”

Consequences for Armenia and the Path Forward

There are, of course, theories that Turkey is not sincerely deepening relations with Russia, but rather either playing both sides or attempting to balance relations in order to maximize its gains. If either theory is true, Turkey is doing a poor job. Just in December 2020, the Trump administration slapped additional sanctions on Turkey’s defense industry office and several top officials. More recently, Biden’s administration has hinted at more sanctions against Turkey.

Regardless of the reasons behind Turkey’s pivot toward the east, for Russia, the significance is obvious—Turkey’s pivot has been an opportunity to achieve a national security objective. Russia views NATO as a threat of the highest order. Indeed, Russia’s national security strategy since at least 2014 has formally designated NATO a national security threat. So, it should be no surprise that a NATO without Turkey—or a less committed Turkey—would be a significant win for the Russians.

Unfortunately for Armenia, it appears to have failed to recognize the Russian-Turkish partnership, and how that partnership may collide with Armenia’s national interests. While we don’t know exactly what factor Russia’s relationship with Turkey played in the recent Karabakh War, a tolerant Russian attitude toward Turkish involvement in the war could have certainly been a way for Russia to reward Turkey and encourage a further deepening. It is also a credible explanation for why Russia hardly blinked at the fact that Turkey transported Syrian terrorists to the Caucasus to help Azerbaijan in the war—something most analysts never thought Russia would allow.

Of course, expanding its relationship with Turkey was not the only win for Russia. Russia is now the exclusive peacekeeping force in Karabakh, having excluded the possibility of Scandinavian peacekeepers. At the same time, the Russian presence in the remaining parts of Karabakh ensures its continued influence and leverage over both Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Meanwhile, Russia can disclaim any responsibility for the 2020 Artsakh War, which in Armenia is mostly blamed on the lack of preparation by the current and previous governments.

So, how should Armenia manage in light of this Russian-Turkish partnership? First, the Armenian leadership and Armenians should be clear-eyed about it and recognize the reality that Turkish-Russian relations are expanding—at least for now. In fact, Armenians should not be surprised if the opening of communication and transit lines required by the November 9, 2020 ceasefire agreement is a precursor to Azerbaijan and Turkey being invited to the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

Second, Armenia must work to solve its security issue. This means that Armenia must deepen its military relations with Russia and other traditional allies. While this might appear counterintuitive in light of Russia’s relationship with Turkey, the reality is that Russia is the only credible security partner to Armenia at the moment. Aside from regularly expressing concern, the West did nothing significant to prevent or stop the recent war. In fact, Armenia should be weary of empty security promises from the West, lest it gets dragged into a larger conflict between NATO and Russia.

Third, parallel with deepening its relations with Russia, it is critical that Armenia modernizes its military to deal with 21st century warfare tactics. While Armenia shares a military alliance with Russia, Armenia must also be able to guarantee its own security.

There may certainly be other steps Armenia can take. However, if it wants to successfully navigate these dangerous times, Armenia’s leadership must take into account the reality that Russia has partnered with Turkey, and then consider the ramifications this presents for Armenia and Artsakh.

also read

Armenia’s New Security Architecture: Russia as Geopolitical Bodyguard

By Nerses Kopalyan

Armenia needs to reconfigure the political economy of its security architecture by utilizing its security alliance with Russia, through a mechanism of burden-sharing, where Russia’s geopolitical interests are aligned with Armenia’s security interests.

Bayraktars Over Artsakh

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

Armenia’s air defense systems were largely ineffective against the onslaught of combat and reconnaissance UAVs used by the Azerbaijani military. The single most important UAV used in the 2020 Artsakh War was the Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2.

Implications of the 2020 Artsakh War on Regional Countries

By Hovsep Kanadyan

The 2020 Artsakh War changed the geopolitical picture in the South Caucasus, impacting all the countries in the region. While there were clear winners and losers, some countries both won and lost.

The 2020 Artsakh War: What the World Lacks Now Is Leadership

By Daniel Tahmazyan

The isolationism of former global powers in a fractured world has left vulnerable countries at the mercy of power-hungry regional players.

Turkish, Western Self-interest Behind Artsakh Bloodshed

By Ave Tavoukjian

As the hordes mass at Armenia’s gates, the U.S. and Europe, the supposed guardians of peace and justice, remain reluctant to intervene to halt the violence due to self-interest and capitulation to Turkish blackmail.

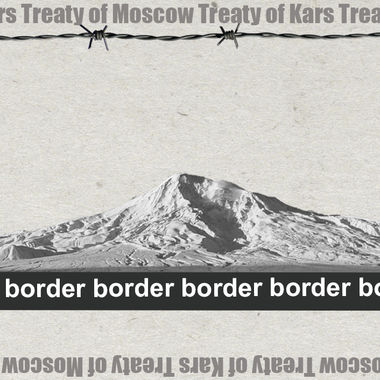

Between Armenia and Mount Ararat Stands a Double Layer Fence

By Justin Tomczyk

Justin Tomczyk traces the history of the Armenian-Turkish border spanning from Armenia’s incorporation into the USSR to the present day, touching upon the Zurich Protocols and reflecting on the viability of a future normalization process.

Turkish, Azerbaijani Identity Void and Genocide

By Paul Mirabile

Is it necessary to assimilate or exterminate a people to affirm one's identity? Has an Azerbaijani identity been founded upon the genocide of a people, who, like in Turkey, lived side by side with the Turkic populations until the rise of nationalism?