The relationship between Russians and Armenians has been a centuries-long one that has seen the incorporation of Armenian lands into the Russian Empire, the creation of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic and the present-day ties between the two states. The Russian question in Armenia is as salient as ever following Moscow’s facilitation of the November 9 ceasefire agreement that ended the 2020 Artsakh War. For some, the discussion has turned into a question of whether Armenia should pursue “more Russia or less Russia.” However, the reality of the matter is that geography is inescapable. Although lacking a direct land border, Russia is undeniably Armenia’s most strategically important neighbor.

Russo-Armenian Historical Relations

The relationship between Armenians and Russians picked up in the 18th century with the contact between the meliks (princes) of Karabakh and Peter the Great, whose Persian Campaign of the 1720s exhibited Armenian involvement. “However, this did not result in the immediate incorporation of Eastern Armenia into the Russian Empire,” explains Dr. Pietro Shakarian, a Cleveland-based historian and analyst of Russia and the post-Soviet space. That process would take off in 1801, when the Russian Empire incorporated the Eastern Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti.

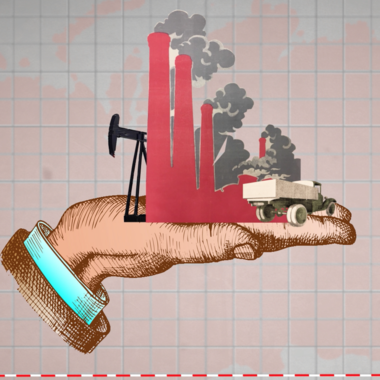

Given that the newly-incorporated lands of Kartli-Kakheti were only connected to the Russian Empire through one road, the Georgian Military Highway, the Russians needed to take more territory around Kartli-Kakheti to resolve the security dilemma that had come from incorporating this new land into the growing empire. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the Russian Empire would incorporate more land throughout the South Caucasus, including Eastern Armenia and Baku, and eventually the entire North Caucasus as well.

“For Armenians, Russia was the only force that was able to provide security guarantees from Turkish and Persian invasions, attacks and massacres–as well as imperialism. This was especially felt following 1915, as the Russian Empire was well into World War I and the Tsarist system was beginning to unravel,” notes Dr. Shakarian. “To many Armenians, the genocide represented what would happen if Russia wasn’t there.”

Under the Soviet Union, Armenia initially found peace during Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP) of the 1920s. However, this moment of freedom ended with the rise of Joseph Stalin to the Soviet leadership. In the 1930s, like all other Soviet republics, Armenia suffered greatly from the Stalinist Terror. Yet, after Stalin’s death in 1953, it also became one of the first places in the USSR to experience the new freedoms of Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw. Dr. Shakarian, who studies the Armenian-Soviet statesman Anastas Mikoyan, stressed the importance of Mikoyan’s speech in Yerevan of March 1954, in terms of framing a reformed Soviet nationality policy and testing the waters for de-Stalinization.

“Armenia played a central role in de-Stalinization in many ways,” he said. “As soon as Mikoyan mentioned the name of the poet Charents, a victim of Stalin’s repressions, everything began to change. It was a signal to Soviet citizens that change was coming. It enabled the process of the rehabilitation of political prisoners.”

Dr. Shakarian identified rare draft notes that Mikoyan wrote for his 1954 speech held in the Russian State Archive. In these notes, he candidly expressed his sentiments regarding Russo-Armenian relations, writing that, “under the yoke of the Turkish Sultan and Iranian Shah, the Armenian people were not only deprived of their independence and statehood and were not only subjected to barbaric and feudal serf exploitation and extortion, but also faced the threat of final physical annihilation [referring to the 1915 Genocide]. The tragic fate of the western Armenians under the yoke of the Sultan showed unequivocally what awaited the Armenian people if they did not unite with Russia.” Of course, one must take Mikoyan’s comments with a grain of salt, given his own standing within the Soviet hierarchy. But nonetheless, he was an Armenian and the sentiments he expressed were widely shared among his Armenian contemporaries.

According to Shakarian, “Looking at the historical trajectory of Russo-Armenian relations, they were quite beneficial for Armenia. Today, for Armenia, it is the most important relationship.”

War in 2020

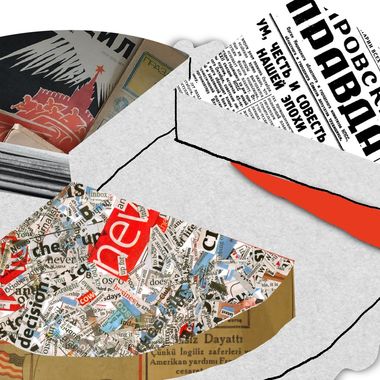

The outcome of the 2020 Artsakh War has left the Republic of Armenia and the Armenians of Artsakh in complete disarray. The results of the war and the subsequent agreements completely altered what had been the status quo for the last 25 years. As is often the case following a devastating loss, the defeated side will search desperately for someone to blame. In Russian history, this question of who is to blame [kto vinovat?] has become a common query in times of trouble [smuta]. As we have seen since the events of the night of November 9, when the cease-fire agreement was signed, both the Armenian state and the Armenian people have been searching for who to blame for their woes.

Some of these claims have more truth to them than others, while some remain in the realm of outlandish conspiracies. Given the relationship Armenia shares with Russia and its involvement in the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), it is important to understand how Russia views its key interests and how they were at play during the 2020 Artsakh War.

The Turkish-backed Azerbaijani onslaught that began in late September of last year also included Sunni jihadist mercenaries, recruited from Syria. Since the 1990s, Russia’s North Caucasus, which border Azerbaijan, has proven to hold secessionist minded groupings, willing to use terrorism as a means to achieve their goals. For Russia to allow jihadi mercenaries to enter the South Caucasus, mere miles from the borders of Dagestan and Chechnya, is unthinkable. Furthermore, Russia has no interest in destabilizing the South Caucasus and would much prefer that any disputes near its southern border be resolved diplomatically.

Dr. Shakarian makes clear that, “regardless of Ankara’s past cooperation with Moscow, for a NATO member to intervene in the post-Soviet space, and to be invited in by another former Soviet Republic, is crossing a major red line. It is something that the Russians don’t like at all.” Indeed, Turkey’s involvement in this most recent war offers a serious challenge to Russian hegemony in the Caucasus, further undermining the balance of power and stability in the region. “The idea or theory that the Russians started the war is not only ridiculous, but contradicts the whole logic of Russian security interests in the region,” adds Dr. Shakarian.

None of this is to deny that the outcome of the war as it regards the nine-point November statement and the subsequent discussions on trade corridors offers benefits to Moscow. To be sure, the Kremlin is highly skilled at diplomatic engagements, including between conflicting parties. However, this does not prove that Russia launched or tacitly approved the start of this war. As is clear from the actions taken during the war, at least two of Russia’s most important national interests, as outlined by Simon Saradzhyan of Harvard’s Belfer Center, were brought into question–which is unacceptable to Moscow.

Dr. Shakarian emphasizes that what Armenia must take away from history is not that Russians or Soviets are “inherently evil,” but that Armenia itself “needs to be prepared for even the worst eventuality.”

What Is To Be Done?

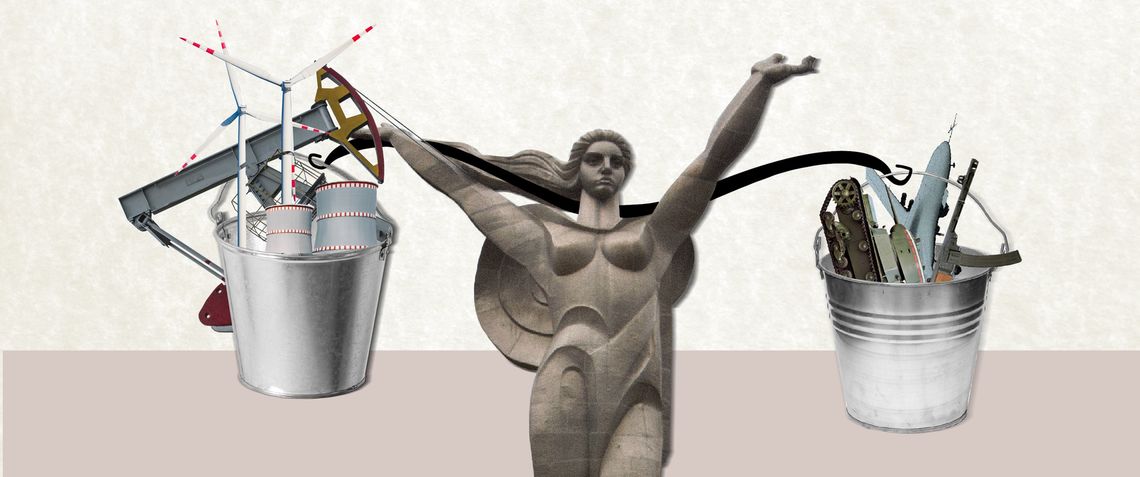

The center of global trade is shifting to the Eurasian continent and Armenia should work to identify its role in this space so as to maximize its potential benefits. By no means does this reality limit Armenia to the east and forbid it from looking to the EU and the West as a whole. “Ideally,” Dr. Shakarian stresses, “Armenia should have access to the best of both worlds.” Nevertheless, Yerevan should be clear-eyed when making decisions about its foreign policy and actions that may have consequences for its longstanding relationships.

Armenia must now look ahead. Instead of reliving the past, the Armenian leadership must get its house in order and offer a unifying vision for the future. Many ideas have already been raised and presented from a range of thinkers, the real task now lies in the current and future government’s ability to hone a vision for the Armenian people moving forward. A truth commission is needed to understand the shortcomings of the war effort and the strategic failures in preventing its occurence. However, there must also be discussions on how the country can develop smart, multilayered and stronger strategies moving forward.