Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Dear Vladimir Ilyich,

The Turkish delegation is coming to Moscow with our representative Behbut Shakhtakhtinski. I have spoken at length with the Turkish delegation here. I do not doubt that the honest Ankarians wish to seal their fate with us against England. The Armenian question is the most sensitive issue for them, and they made every effort to resolve it in their favor. When I mentioned Batumi and Akhaltsikhe, they said, “The Armenian question, for us, is a matter of life or death. If we concede on this issue, the masses won’t follow us. However, if we resolve this issue in our favor, we will come out strong.”

This was how Nariman Narimanov, Chairman of the Soviet Azerbaijani Revolutionary Committee, presented the Kemalist position on the Transcaucasian borders to Lenin in February 1921. The official Turkish delegation was rushing to Moscow to participate in the second Russian-Turkish Conference, where a treaty on friendship and brotherhood between Russia and Turkey was to be signed.

The Treaty of Moscow regulated the border issues between the Kemalists and the Bolsheviks, both of which were still fighting civil wars. It represented a capitulation of Armenian claims. The Russian-Turkish Conference was shrouded in numerous myths and surrounded by real and fake information—just like many other events between 1918 and 1920.

Soviet historiography rarely touched upon the controversial parts of the Treaty of Moscow; the Bolsheviks’ cooperation with Kemal was not to be criticized and doubted. Only near the end of the USSR did articles, archival documents and testimonies appear in the press and gradually shed light on the geopolitical issues prevalent in the 1920s. The story of the Treaty, signed on March 16, 1921, starts with the 1920 Turkish-Armenian War, and in some ways even before that, up until Turkey’s acceptance of its “National Oath,” Azerbaijan’s Sovietization and other related events.

During the Turkish-Armenian War, which took place from September to November 1920, Armenia was seriously defeated. Terms were imposed by Turkey in the Treaty of Alexandropol, which was signed on December 3, the day after the Armenian government of the First Republic handed power over to the Soviets. In the capitulation, Armenia renounced the Treaty of Sevres. Though the treaty was never ratified, the territorial losses would be confirmed in the Treaty of Moscow, signed several months later.

With the Treaty of Alexandropol, the Republic of Armenia was obliged to call back its delegations from Europe and turn away all official representatives of the Allied Powers. The Armenian Army would be limited to 1,500 soldiers and 1,500 officers. If Armenia were to be attacked, Turkey would be obliged to protect it, if the Armenian government asked for help from the Turkish side.

The Treaty referred to the Turkish-Armenian border in Articles 2 and 13. The provinces of Kars and Surmalu, which had been part of the Russian Empire prior to World War I but had been captured by Kemal’s army, were considered contested land. Within three years, Armenia’s government could hold a referendum in these provinces. However, it was clear to everyone that a defeated Armenia would not be able to hold the referendum. Even if it could, the remaining Turkish population, which had almost entirely driven out the Armenians from those provinces between 1918 and 1920, would vote for the contested lands to become part of Turkey. Article 13 gave autonomy to Sharur and Nakhichevan under Turkish sponsorship. Hence, with the Treaty of Alexandropol, Armenia lost Kars, Surmalu and Nakhichevan.

The Treaty was to come into force once the two countries’ governments ratified it within a month. Neither Turkey’s Grand National Assembly nor Armenia’s parliament ever ratified the treaty. Furthermore, Armenia’s delegation had no authority to sign that agreement because, on December 2, 1920, Armenia’s government had resigned and handed over Yerevan’s rule to the Bolsheviks. Thus, the Treaty of Alexandropol had no legal force, which the Kemalists and the Armenians and Russians understood well. It was vital for Turkey to secure the results of the war quickly. Hence, in December 1920, the Turkish side appealed to the Soviet government to hold a Russian-Turkish Conference. Besides this, it was necessary to regulate the relations between Kemalist Turkey and Soviet Russia, which were considerably tense. In November 1920, when Kemal’s forces were entering Kars and Alexandropol, Soviet Russia stopped providing the Turks with weapons, fuel and gold, which posed a serious threat to the Turkish National Movement, which was also carrying out military operations against the Allies.

“The retaliation by Soviet Russia took place at the beginning of November ,when the Turks had already captured Alexandropol,” writes historian Ararat Hakobyan.[1] “The Soviet government, led by Georgi Checherin, found it appropriate to temporarily cease delivering weapons to Turkey.”

Soviet Russia stopped providing weapons to Turkey for another, more serious reason: Turkey was trying to play a double game and establish relations with the West—that is, with France and England. The government of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) sent a note to Kemal’s government on December 9, 1920, stating that it agreed to hold a conference in Moscow. “The Russian Soviet government [...] finds it necessary to also have representatives of the governments of Soviet Armenia and Azerbaijan take part as well because there are land and other issues that need to be resolved between these states and Turkey and Russia,” Chicherin wrote.[2]

The next day, Chicherin wrote to Aron Sheinman, the Soviet Russian representative in Georgia: “Attempts of reconciliation between the Entente and the Kemalists are not succeeding… It’s unacceptable for Batumi to pass to the Turks. We should not stray from our friendly policy toward the Kemalists. However, we have to keep them away from actions that are unacceptable for us. Sergo [Ordzhonikidze] has received the order to restart providing weapons and gold. Since the gold is with you, hand them over incrementally following Sergo’s orders.”[3]

There are opinions that the aim of the Russian-Turkish Conference in Moscow was to review the articles on territorial division laid out in the Treaty of Alexandropol. This opinion is not correct because, as was mentioned, the Kemalists first proposed to hold the conference in November 1920, before the Alexandropol Treaty was signed. Some Armenian Bolsheviks had expectations of reviewing the Treaty of Alexandropol. Even though they were committed to internationalist revolutionary ideology, they did still have some patriotism and wished to mitigate the consequences of that catastrophic treaty to the extent possible. After coming to power, the Revolutionary Committee hoped that Turkey would act fairly toward Soviet Armenia; they thought that the Kemalists fought against an Armenia that was “an ally to the imperialists,” and that now, with Soviet rule established in Armenia, there was an “ideological commonality” with the Kemalists.

On December 10, 1920, Armenia’s Foreign Affairs Minister Aleksandr Bekzadyan wrote a telegram to Ahmed Mukhtari, the Ankara government’s Foreign Affairs Minister, and Kazim Karabekir, Commander of the Eastern Front. “When the leaders of the Dashnaktsutyun party [Armenian Revolutionary Federation, ARF] were arrested by the rebellious people or fled Soviet Armenia, their forgotten reconciliation delegation in Alexandropol signed an agreement. The terms of this agreement are new evidence that the Dashnaks are not fated to deliver anything useful to Armenia’s popular masses…,” wrote Bekzadyan.[4] “The Soviet authorities are hoping that you will officially annul the signed peace deal with the Dashnaks and propose holding a conference soon to come to a new agreement arising from the new conditions brought forth by the revolutionary coup.”

The preparation stage for the Treaty of Moscow was very important. By the end of 1920, Kemalist Turkey had significantly improved its position in the region. Besides its victory over Armenia, Turkey was successful in the western front as well; Greek pressure had significantly weakened. The Entente's attitude was also changing toward the Kemalist movement, which was growing day by day; England was trying to use the Turks against Soviet Russia, who it was fighting against. This gave Turkey great opportunity to maneuver the situation. The hints Kemal was giving the West seriously worried the Bolsheviks, who were ready for concessions to keep Turkey within its field of influence. In this sense, Narimanov’s advice to Lenin was no coincidence: “If Moscow repels Ankara because of the Armenian Question, then they will despairingly jump into the West’s lap.”[5]

One of the important issues during the Russian-Turkish Conference was the city of Batumi. The issue was that the Turks wanted to have Batumi, a desire which was established since their “National Oath” was approved on January 28, 1920. According to that oath, the Kemalists’ aim was to restore the borders prior to the 1877-1878 Turkish-Russian War, which included Kars and Batumi. In turn, the Bolsheviks wished to establish Soviet rule over Georgia, without which their rule in Transcaucasia would not be complete. Turkey’s invasion into Georgia would have been an opportune moment for sovietization; however, the Kemalist aspirations could have been dangerous for Batumi. On December 31, 1920, Stalin wrote to the Soviet Union’s representative Budu Mdivani, telling him not to allow Turkey’s advance toward Batumi. “For now, we cannot trust them,” wrote Stalin. “They are very cunning.”[6]

The date for the Russian-Turkish Conference was finally decided by the end of 1920. However, Turkey wished to exclude the Armenian Question at all costs. The first step toward this was to prevent the participation of the Armenian delegation. In the beginning of 1921, the Turks stated that they did not trust the Revolutionary Committee and the Armenian communists in general. One of the reasons they brought was Dro’s presence in the ruling regime. In 1921, hundreds of Armenian officers, including Drastamat Kanayan (Dro), were exiled from Armenia.

More than Batumi, the Turks wished to keep Nakhichevan under their influence as well. Nakhichevan had an extremely important strategic importance for them. For one, it allowed them to establish connections with Azerbaijan to the east. Additionally, it was a region that had a dominant geographical position over Armenia.

Even by the end of 1918, after being defeated in the First World War and leaving Transcaucasia. Turkey maintained its influence over Nakhichevan at all costs. Turkish officers and agents would agitate Nakhichevan’s Tatar population, providing them with weapons and ammunition, and carrying out active organizational work.

After the Bolsheviks returned and the first clash with Armenian armed forces took place in Zangezur, the Russian-Armenian agreement, signed August 10, 1920, declared Nakhichevan to be contested land between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and Soviet troops were brought in there. This agreement gave Armenia the right to make use of the Sharur-Shaktakht-Julfa railway. After Armenia’s defeat during the Turkish-Armenian War in 1920, the Turks tried everything they could to have that railway fall under their complete control. As was mentioned, the Treaty of Alexandropol foresaw that Nakhichevan was to be an autonomous region under Turkey’s sponsorship.

After the establishment of Soviet rule in Armenia, representatives of Azerbaijan’s Revolutionary Committee announced to the world that Nakhichevan and Zangezur had to be within Armenia’s borders. This excited the Armenian Bolsheviks and deeply worried Turkey. At the end of 1920, when the main points of discussion of the Russian-Turkish Conference were being finalized, the Turks further intensified their operations in Nakhichevan. In January 1921, Veysal Bey, the Commander of the Turkish troops in Nakhichevan, tried to overthrow the Soviet regime twice. However, he was not able to succeed.

Behbut Shaktakhtinski, a member of the Azerbaijani Revolutionary Committee who held a pro-Turkish stance, fostered pro-Turkish sentiments in Nakhichevan. In January 1921, he told residents of Nakhichevan, “Azerbaijan sold you. If I were in Baku, I would not have allowed it… I’m leaving… Now you should look toward the Turks. They are your only salvation.” Hence, it was clear that both the Turks and the Azerbaijanis were doing everything so that Nakhichevan would not become part of Soviet Armenia.

The Turks, however, did not stop with their actions in Nakhichevan. At the end of December 1920, they closed off all the roads and the railway between Armenia and Nakhichevan. Nearly a month later, Nakhichevan’s Extraordinary Commissioner Velibekov started reporting worrisome information about the conduct of the Turks. “Recently, Turkey has been flirting with the Entente and with us as well. The latest facts have shown that it is leaning toward the Entente,” wrote Velibekov.[7] “It wished to capture Nakhichevan as a wedge to carry out its plan: to arouse a general anti-revolution starting from Anatolia, Maku, Nakhichevan, Persian Azerbaijan and ending with Soviet Azerbaijan.”

Turkish pressure on Soviet Russia on the Nakhichevan issue continued in February 1921 as well, when the date for the conference was finally set. In the beginning of February, at the instigation of Turkish agents, a new riot broke out in the village of Zahri, during which Soviet regime representatives were arrested. At the same time, the Turks armed local forces in Julfa—near 800 men—who were to go help out in Zahri. However, the subunits of the Red Army were able to stop the riot. On February 3, 1921, Velibekov reported that the Turks had a “certain hostile” stance toward representatives of the Soviet regime. “Their aim is to capture Nakhichevan and, to realize this, they are taking every measure,” wrote Velibekov.[8] “Since they do not have real great forces in Nakhichevan, they are trying to use local anti-revolutionary elements.”

The next episode of antirevolutionary actions included Veysal Bey, Commander of the Turkish military base, declaring himself the Extraordinary Commissioner of Nakhichevan. During this time, the February Uprising was taking place in Armenia and Veysal Bey told the Bolsheviks that the Armenians were preparing to invade Nakhichevan. This was why, according to him, he was taking the protection of Nakhichevan upon himself. The Turkish commander also wanted to declare partial conscription, which the Soviet authorities were able to prevent.

The Azerbaijanis were also actively working against the unification of Nakhichevan with Armenia. Narimanov’s well-known announcement was a tactical trick and most probably was meant to promote Armenia’s sovietization. In March 1920, Behbut Shakhtakhtinski informed Russia’s Communist (Bolshevik) Party’s Central Committee’s Caucasian Bureau that handing over Zangezur and Nakhichevan to Soviet Armenia weighed heavily on Karabekir. “Karabekir honestly said that it was the greatest tragedy for Turkey and not beneficial for Russia if they did not understand each other,” wrote Shakhtakhtinksi.[9] To normalize relations with Turkey, Shakhtakhtinksi proposed that Nakhichevan turn into an autonomous administrative unit under the auspices of Russia. “This strategic corner cannot be given to the Turks,” Shakhtakhtinski wrote. “Turning the region autonomous, we can assume, will suffice for the Turks as well.” Thus, through diplomatic and military initiatives, step by step, the idea of having Nakhichevan part of Soviet Armenia was pushed off the agenda.

In the beginning of February 1921, a Turkish delegation headed by Yusuf Kemal (Mustafa Kemal’s brother) arrived in Baku. The delegation was respectably large with 45 members, including Ankara’s ambassador to Moscow Ali Fuad Pasha (Jebesoy) and Riza Nuri Bey. On February 6, they left Baku accompanied by Shakhtakhtinksi and arrived in Moscow on February 18.

The Armenians were also preparing for the Moscow Conference. In December 1920, members of the Armenian Revolutionary Committee Askanaz Mravyan and Sahak Ter-Gabrielyan met with Lenin, Trotsky and then with Deputy Foreign Minister Levon Karakhani in Moscow. However, the leaders did not give them much hope. On December 26, 1920, Mravyan sent the following note to Yerevan from Moscow: “Moscow’s position is not that clear… After listening to us, Lenin said that the social essence of Ankara understands and is of the same opinion that they are against communism. However, he is sure that there have been uprisings within Turkish peasants and as an example mentioned Konya’s Bolshevik uprising. In his opinion, clashes between the Red Army and Turkish military units will end badly. In response to our assurances that that will not happen, he said, ‘I am of another opinion.’ Later, he [Lenin] said, ‘Understand comrades, Moscow does not and cannot go to war at this time, especially for Kars.’ Lenin believes Kars is a Turkish city. When we mentioned the heavy situation the Armenian people were in, which could affect the reputation of the Communist Party in the eyes of the Armenian worker, we received the following reply: ‘We are forced to sacrifice the Armenian worker’s interests temporarily for the interests of international revolution. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania also had the same fate. Right now, we can help Armenia with money and food, as well as station so many soldiers in Armenia that Ankara yields.’”[10]

Chicherin did not accept the Armenians and sent them to Karakhan. The latter told them it was not possible to make any concessions around the issues of Kars and Nakhichevan. “I don’t find it prudent to turn the issue of Kars into the reason why we would break off relations with Ankara,” he told them.

The Armenian side had prepared an extensive information package to be presented during the Moscow Conference, which included maps, references and statistical data. The Armenian delegation reached Moscow on February 18, 1920, in the same train as the Kemalists. As soon as they arrived, the Turks declared that Armenia and Azerbaijan should not take part in the conference because they had no authority to negotiate with them. The Russians agreed.

By the time of the conference, Turkey’s international position had only gotten stronger; they had come out victorious against the Greek army in Smyrna during the months of January and February. Besides this, the Entente conference had taken place in London, where their attitudes toward Turkey had changed. In London, the provisions of the Treaty of Sevres were significantly reduced; the demand for a united and free Armenia was replaced by the idea of a “national home.”

“It’s clear that the West needed Armenia in their fight against Bolshevism,” writes historian Ararat Hakobyan. “When they were convinced that Armenia was not able to fight against Bolshevism nor protect its own borders against the Soviet-Kemalist invasion, in practice, they lost their interest toward Armenia.”

On February 21, 1921, the Turkish delegation met with Stalin, who was then the People’s Commissar for Nationalities. He told them that the Armenian question would not be discussed during the conference. Foreign Affairs Minister Chicherin and then later Lenin himself also assured them of this.

During the Moscow Conference, Georgia’s sovietization was underway. It was at this time that the Turkish troops took Ardahan and approached Batumi. In the beginning of March, a not-so-large Turkish unit entered the city, which deeply dissatisfied Soviet authorities. The Red Army quickly reached Batumi.

With the Treaty of Moscow, Nakhichevan received autonomy within Azerbaijan on the condition that it could not be handed over to a third party—in this case, Armenia. The city of Batumi and its port remained within Soviet Georgia. The Treaty of Moscow reaffirmed, almost identically, the borders laid out in the Treaty of Alexandropol. Armenia, thus, conceded 20,000 square kilometers to Turkey. However, what did change were the articles of the Treaty of Alexandropol which gave Turkey the right to interfere in Armenia’s internal affairs. It limited the number of troops which was what worried the Russian side the most.

Turkey was able to maximize its results through negotiations, by conducting a flexible policy between Russia and the West and by demonstrating military force. The Armenian side sent complaints to the Central Authorities; however, their attempts were in vain. Armenia had lost in the war, and complaints alone could not reverse those losses.

------------------------

[1] Ararat Hakobyan, “Soviet Armenia in the Treaties of Moscow and Kars,” Yerevan, 2010, p. 36.

[2] From Armenia's international diplomatic and Soviet foreign affairs/policy documents, Yerevan, 1972, p. 464.

[3] USSR Foreign Policy Documents, vol. 3, Moscow 1959, p. 374.

[4] Armenia in International Diplomatic and Soviet Foreign Policy/Affairs Documents, Yerevan. 1972, p. 66.

[5] Nagorno-Karabakh in 1918-1923, Collection of documents and materials. Yerevan 1992., p. 615.

[6] Ararat Hakobyan, “Soviet Armenia in the Treaties of Moscow and Kars,” Yerevan, 2010, p. 108.

[7] Edik Zohrabyan, The Key Issues of Nakhijevan (May 1920-October 1921), Yerevan, 2010, p. 254.

[8] Ibid, p. 260.

[9] Yu.G. Barsegov, Armenian Genocide. Turkey's Responsibility and the Commitment of the World Community, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 405.

[10] Yu.G. Barsegov, Armenian Genocide. Turkey's Responsibility and the Commitment of the International Community, Volume 2, Part 1, pp. 336-337.

Magazine

Issue N4 / PAST

Under the careful curation of historian and guest editor Suren Manukyan, the February 2021 issue delves into the past to try and understand the present.

More than ever, revisiting historical events through a new lens is essential for the Armenian people.

From a Fateful Revolution to the Dream of Pan-Turkism: Causes of the Armenian Genocide

By Suren Manukyan

Turkey continues to fight against the recognition of the Armenian Genocide through falsification of history, anti-Armenian propaganda, using all political, economic and lobbying levers at its disposal.

The Fall of Kars: A Look to the Past

By Mikael Yalanuzyan

Armenia’s defeat and the loss of land in Artsakh took place exactly 100 years after the Turkish-Armenian War of 1920. Armenian society started drawing parallels between the fortress cities of Kars and Shushi.

Attempts to Restore Statehood and Armenia’s Last Crowned King

By Smbat Hovhannisyan

Following the fall of the Kingdom of Cilicia in the 14th century, attempts were made to restore the Armenian Kingdom with Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni, the last crowned king of the Armenian people.

The Pearl of the Mediterranean: Cilician Armenia at the Crossroads of East-West Trade

By Zohrab Gevorgyan

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia consolidated and synthesized cultures, giving new breath to the traditional, by creating a new, more complete Armenianness. Surviving for 300 years demanded tremendous civilizational potential from the Armenian people.

Conversion to Christianity and the Creation of the Armenian Alphabet

By Shavarsh Azatyan

The secular, religious and cultural elites of what became Armenia’s Golden Age were able to turn challenges into a stimulus, setting in stone the Armenians' mark over their territory that would last for centuries.

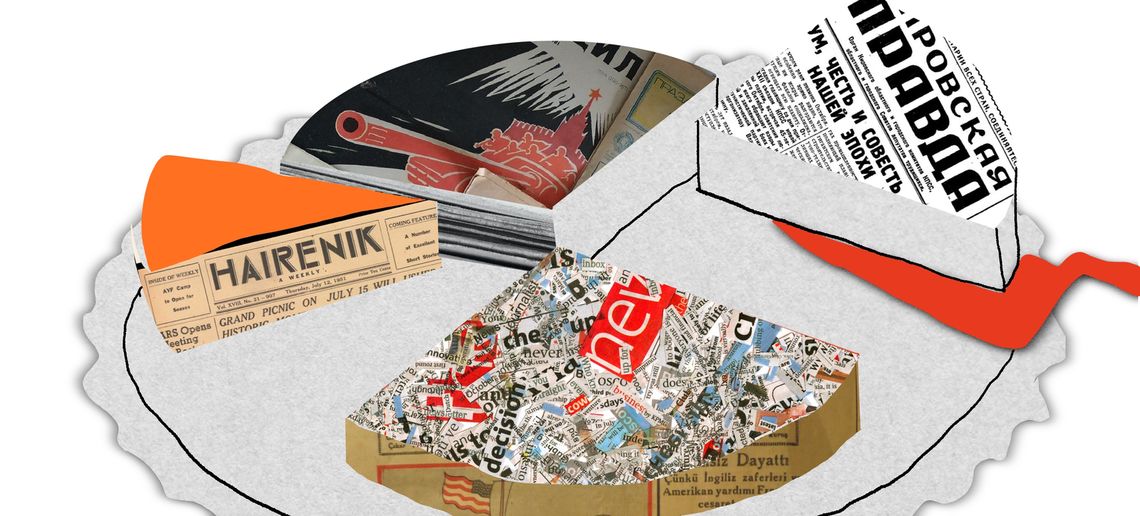

Issue N6 / Diaspora

Ahead of the 106th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, observed on April 24, EVN Report’s April issue entitled “Diaspora” focuses on the realities of the Armenian diaspora and attempts to understand the multi-layered, multi-dimensional nature of the ever-changing Armenian diaspora. Today, in the post-war reality, it is important to redefine and recalibrate the relationship between Armenia and its diaspora.

Ground Zero: Back to the Question of the Diaspora

By Khatchik DerGhougassian

Will the 2020 Artsakh War be a turning point for the diaspora to reassess and define a new agenda for itself? Dr. Khatchik DerGhougassian argues that a paradigm shift has started to occur in how the diaspora sees itself and its relationship with the homeland.

Diaspora Conceptualizations and the Realities of the Armenian Diaspora: Some Preliminary Observations

By Vahe Sahakyan

Do diasporas have agency, imagined and conceptualized, to produce collective behavior or are they too vast and heterogeneous to generate any coordinated collective action in unison?

A Defining Moment for the Armenian Diaspora? Some Preliminary Reflections

By Sossie Kasbarian

The 2020 Artsakh War was perceived and experienced in Armenia as well as in the diaspora as an existential crisis. Kasbarian argues that the recent nation-wide mobilization made this moment a transformative one.

Post-War Reflections From the Diaspora

By Lalai Manjikian

The diaspora must continue to invest in rebuilding and channeling diasporic potential following the 2020 Artsakh War. This is not 1915, writes Lalai Manjikian, the nation has a huge pool of educated, driven and competent forces.