Thu Apr 23 2020 · 10 min read

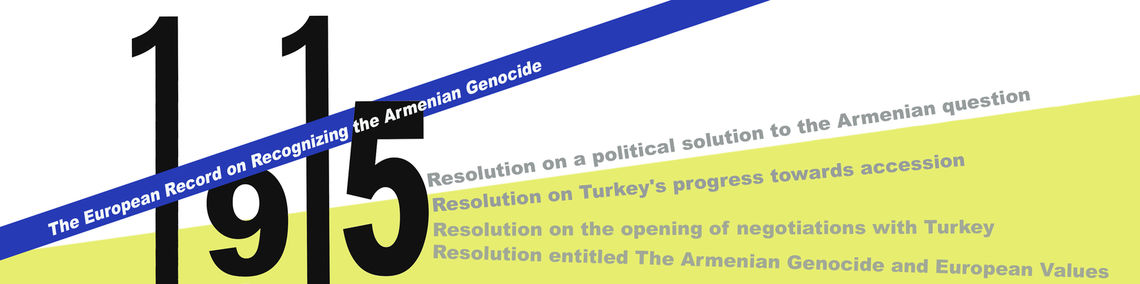

The European Record on Recognizing the Armenian Genocide

By Anna Barseghyan

Despite persistent denial from the Turkish government, the Armenian Genocide has been recognized by a number of governments and international organizations. In the United States, 2019 was an important year in this regard as Alabama became the 49th U.S. state to do so, followed by the District of Columbia, the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate in the fall. Eighteen European countries recognize the Armenian Genocide. The European Parliament has adopted five resolutions affirming its stance. Some of these resolutions directly led member states to adopt similar documents at the national level.

The first European state to recognize the Armenian Genocide was Cyprus in April 1982, after it had been the victim of a Turkish invasion in 1974.

In 1987, the European Parliament (EP), one of the bodies of the European Communities including representatives from Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Italy, West Germany, Ireland, United Kingdom, Denmark, Greece, Spain and Portugal, adopted its "Resolution on a political solution to the Armenian question,” a remarkable document which recalls the definition of genocide as adopted by the UN General Assembly’s 1948 Genocide Convention. The resolution states that the European Parliament “believes that the tragic events in 1915-1917 involving the Armenians living in the territory of the Ottoman Empire constitute genocide within the meaning of the convention on the prevention and the punishment of the crime of genocide adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948.” The second part of the paragraph is less encouraging, however: “Recognizes, however, that present Turkey cannot be held responsible for the tragedy experienced by the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire and stresses that neither political nor legal or material claims against present-day Turkey can be derived from the recognition of this historical event as an act of genocide.”

It is a carrot and stick policy that the EU, called the European Communities at the time, used against Turkey. On the one hand, it mentioned the historical fact of the genocide, but on the other, suggested it would not hold it against the Turkish state. The EP called on the European Council to obtain from the Turkish government the recognition of the Armenian Genocide and promote the establishment of a political dialogue between Turkey and representatives of the Armenians. In 1987, Armenia was still within the Soviet Union and deprived of the opportunity to present any demands toward Turkey. That is the reason the resolution refers to the representatives of Armenians, which were mainly diasporan organizations throughout the world.

The resolution upholds the spirit of protecting human rights, mainly the rights of minorities including Armenians living in Turkey, mentions the maintenance and conservation of Armenian religious architectural heritage in Turkey and invites the community to examine how it could make an appropriate contribution. The EP implied that, without the protection of minority rights, Turkey couldn't meet the Copenhagen criteria of democracy, which was a prerequisite for membership in the Communities. Another interesting point in the document is the call to the member states to dedicate a day to the memory of the genocide and crimes against humanity perpetrated in the 20th century, specifically against the Armenians and Jews. The EP summed up the resolution with the commitment to contribute to the negotiations between the Armenian and Turkish people. Though the document didn't carry any legal consequences or an enforcement mechanism, from a political point of view, it offered the Armenian people bargaining power in the negotiations. Unfortunately, it was itself also a bargaining chip for the European Communities to prevent the accession of Turkey. It was a response to Turkish membership aspirations; on April 14, 1987, Turkey had submitted an application to join the European Communities.

After the resolution, there was a long break in the recognition process. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the decommunization of several Eastern and Central European states and the outbreak of several frozen conflicts focused the world’s attention in other areas. Moreover, the government of newly-independent Armenia expressed a willingness to establish relations with Turkey without any preconditions. During this period, in 1996, the Genocide was recognized by Greece.

The circumstances changed in 1998, when a change of government took place in Armenia and the recognition of the Armenian Genocide became one of the foreign policy priorities of the Republic. In 1998, the Belgian Senate adopted a resolution and the French National Assembly adopted a bill. On April 24, 1998, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) published a declaration marking “April 24, 1915 as the beginning of the implementation of the plan to exterminate the Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire,” and mentioning that “Today we commemorate the anniversary of what has been called the first genocide of the 20th century, and we salute the memory of the Armenian victims of this crime against humanity.”

In 2000, the Swedish Parliament prepared a report about the Genocide, France’s Senate adopted a law, and Italy's Chamber of Deputies adopted a resolution.

However, one of the decisive events was the EP’s resolution on “Turkey's progress towards accession,” adopted on November 15, 2000. It is worth mentioning that, at the 1999 EU Summit in Helsinki, Turkey obtained the status of a candidate country for EU membership. In the progress report, the EU “…Calls, therefore, on the Turkish Government and the Turkish Grand National Assembly to give fresh support to the Armenian minority, as an important part of Turkish society, in particular by public recognition of the genocide which that minority suffered before the establishment of the modern state of Turkey;…”

Furthermore, it called on the Turkish government to launch a dialogue with Armenia, aimed in particular at re-establishing normal diplomatic and trade relations between the two countries and lifting the blockade. Of course, the calls of the EP fell on deaf ears from the Turkish side.

The resolution was followed by the adoption of the French law about the Armenian Genocide in 2001. That same year, the 1700th anniversary of Armenia adopting Christianity, His Holiness John Paul II visited Armenia and held a special prayer at the Tsitsernakaberd Genocide Memorial dedicated to the innocent victims of the Genocide.

On April 24, 2001, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted one more statement appealing “to all the members of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe to take the necessary steps for the recognition of the genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire against the Armenians at the beginning of the 20th century.”

The third time the EP mentioned the Armenian Genocide was in 2002, with the resolution EU relations with South Caucasus, where it recalled the 1987 resolution and called upon Turkey to create a basis for reconciliation. The first time the EU took initiative and directly mentioned the need to form an international committee of historians. “The recognition of the Armenian genocide by the European Parliament and by the several Member States and the fact that the Turkish regime after the First World War had several of those responsible for the genocide severely punished ought to provide a basis for the EU to present constructive proposals to Turkey on the handling of the matter, e.g. by setting up a multicultural international committee of historians on the 1915 Armenian genocide.”

Of course, Turkey refused to open its archives to international historians. However, the resolution was a fresh start for recognition by more European states. In 2003, the National Council of Switzerland adopted a National Council Resolution. In 2004, Slovakia’s National Assembly adopted a resolution. Entitled “On the 90th anniversary of the genocide committed on the Armenians in Turkey during the 1st World War,” the Polish Parliament adopted a resolution mentioning, “The Sejm [Parliament] of the Republic of Poland pays its respects to the victims of the genocide committed on the Armenians in Turkey during the 1st World War.” In the Netherlands’ parliament's resolution it “asks the government within the framework of its dialogue with Turkey to continuously and expressly raise the recognition of the Armenian genocide.” In 2005, Lithuania’s Assembly adopted a statement recognizing the Armenian Genocide.

One more time the EP mentioned the Armenian Genocide was in 2005, in the European Parliament resolution on the opening of negotiations with Turkey. Along with resolving its dispute with Cyprus, which is another sore point for Turkey, the recognition of the Armenian Genocide is mentioned as a precondition for Turkey. It explicitly “Calls on Turkey to recognise the Armenian genocide; considers this recognition to be a prerequisite for accession to the European Union."

In 2004, the European Council decided to open membership talks with Turkey and on October 3, 2005, accession negotiations began. At the very onset of the accession negotiations, the Armenian Genocide became one of the preconditions suggested by the EP, however, it was never seriously considered by Turkey. Turkey had so many ongoing issues meeting the accession criteria that the Armenian Genocide remained low in their priorities.

In 2010, the Swedish Parliament adopted a resolution recognizing the 1915 genocide against Armenians, Assyrians/Syrians/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks.

The Centennial of the Armenian Genocide was a new trigger for European countries and institutions to name the Turkish atrocities as Genocide and adopt resolutions stressing the need for recognition of the historical fact by Turkey itself. The statement by Pope Francis during the Mass at the Vatican on April 12, 2015 had a huge influence and was included in the European Parliament's resolution. He mentioned three massive and unprecedented tragedies in the twenty century. “The first, which is widely considered the first genocide of the 20th century, struck your own Armenian people,” mentioned the Pope, adding that concealing or denying evil is like allowing a wound to keep bleeding without bandaging it.

The European Peoples Party’s (EPP) resolution entitled “The Armenian Genocide and European Values’’ is also especially valuable.

The EPP is one of the most influential political party families of the EU. In 2015, of the 751 members of the European Parliament, 219 were members of this party family, and 14 of the 28 members of the European Commission and the European Council were members of the EPP.

The title of the resolution links the recognition of the Armenian Genocide to European values, which seems to set a precondition for Turkey to “adopt a European value system” through the recognition of the Genocide. It is noteworthy that the resolution considers the historical events in a wider spectrum and condemns the genocide committed not only by the Young Turks but also by other Turkish regimes in 1894-1924. The resolution is unique in that, for the first time at the European level, there is talk of material compensation, the return of lands, preservation of cultural heritage, restoration of ancient cities, churches, schools, cemeteries and other strategies for the protection of historical and cultural heritage in Western Armenia.

“We invite Turkey, in the finest example of integrity and leadership proffered by the Federal Republic of post-war Germany, to face history and finally recognize the ever-present reality of the Armenian Genocide and its attendant dispossession, to seek redemption and make restitution appropriate for a European country, including but not limited to ensuring a right of return of the Armenian people to, and a secure reconnection with, their national hearth―all flowing from the fundamental imperative of achieving reconciliation through truth.’’

Of course, such a powerful resolution from the EPP had its reflection in the European Parliament. After a ten year break, the EP once again spoke about the Armenian Genocide in “the European Parliament resolution of 15 April 2015 on the centenary of the Armenian Genocide.” It recalled the 1987 resolution as a basis and called on Turkey to open its archives, to come to terms with its past, to recognize the Armenian Genocide and thus pave the way for a genuine reconciliation between the Turkish and Armenian people.

Moreover, it “Invites Turkey to respect and realize fully the obligations which it has undertaken to the protection of cultural heritage and, in particular, to conduct in good faith an integrated inventory of Armenian and other cultural heritage destroyed or ruined during the past century within its jurisdiction.”

The resolution, which was forwarded to the national governments of the member states was quite impactful. It was followed by a statement by the President of the Federal Republic of Germany Joachim Gauck, the statement of the Austrian Parliament on the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide perpetrated in the Ottoman Empire, the Resolution of the Parliament of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, and the resolution of the House of Representatives of the Kingdom of Belgium. The Parliament of Denmark also adopted a resolution recognizing the Armenian Genocide. Later in 2016, the Bundestag of the Federal Republic of Germany adopted its own resolution, the Senate of France confirmed the bill criminalizing the denial of Armenian Genocide [the bill was later struck down by France’s Constitutional Court]. In 2017, the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic adopted a resolution condemning and recognizing the Armenian Genocide and other crimes against humanity. In 2019, the Parliament of Portugal expressed its position on the Armenian Genocide, the chamber of deputies of Italy encouraged the government of Italy to recognize the Armenian Genocide, and the President of France Emmanuel Macron issued a decree recognizing April 24 as a National Memorial Day of the Armenian Genocide.

Unfortunately, the recognition of the Armenian Genocide is not only a matter of justice, but it is also a compound process, which is only possible when all external and internal factors line up. Sometimes, it is used as a playing card against Turkey to prevent new catastrophes. However, the recent events in Syria and the Turkish invasion of that territory made it clear that statements are not powerful enough if earlier crimes are left unpunished.

The European Union is built on the idea that justice is not optional and human rights cannot be bargained away. There is a need to be more practical and go beyond words and into actions. The Armenian Genocide is not the ghost of the 20th century. As long as new genocides are happening across the world, the Armenian question remains contemporary. To prevent new atrocities, it is vital that old ones are not swept under the rug. Justice has no time limit, especially as the descendants of Armenian Genocide survivors continue to thirst for the fair solution to the Armenian question. We remember and demand.

also read

A Crime Against Humanity, History and Memory

By Maria Titizian

After a decades-long struggle by the Armenian-American community, the U.S. House of Representatives officially recognized the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Maria Titizian writes about the significance of this resolution for her and all Armenians, despite the motivations behind the vote.

Turkey, the Kurds and the Generational Trauma of the Armenians

By Maria Titizian

When Turkey launched its military offensive in northeastern Syria, it triggered something in the minds and hearts and memories of many Armenians.

Between Armenia and Mount Ararat Stands a Double Layer Fence

By Justin Tomczyk

Justin Tomczyk traces the history of the Armenian-Turkish border spanning from Armenia’s incorporation into the USSR to the present day, touching upon the Zurich Protocols and reflecting on the viability of a future normalization process.

International Recognition for the Western Armenian Language

By Harout Manougian

Western Armenian is now officially recognized by the ISO, enabling a Wikipedia site and opening the door for Google Translate, software localizations and more.

How Genocide Survivors Made Yerevan Great

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

From those who survived the Armenian Genocide to those who moved to Soviet Armenia during the Great Repatriation of the 1940s, Western Armenians contributed to Yerevan’s incredible rise as a major city, turning it into the heart and soul of the Armenian nation.

The Armenian Orphans of the Genocide: Separation, Reunion, Loss and Sacrifice

By Arpine Haroyan , Gayane Ghazaryan

Many took the harrowing experience with them to their graves. Others would share only fragments of memories. All of them suffered unimaginable loss. They were the orphans of the Armenian Genocide and their stories must never be forgotten.

A Beautiful Crime: Soghomon Tehlirian and the Birth of the Concept of Genocide

By Suren Manukyan

A survivor of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, Soghomon Tehlirian assassinates Talaat Pasha, the mastermind behind the attempted annihilation of the Armenian nation in Berlin on March 15, 1921. Historian Suren Manukyan examines the repercussions and consequences of that act of revenge.

From the Forgotten Pages of History: The Life and Times of Mari Beylerian

By Arpine Haroyan

Mari Beylerian, a writer, feminist and public figure, is one of the least known intellectuals from Western Armenia. It is said that Mari was one of the two women (along with Zabel Yesayan) who was arrested with over 200 hundred Armenian intellectuals on April 24, 1915. Her fate remains unknown still today.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.