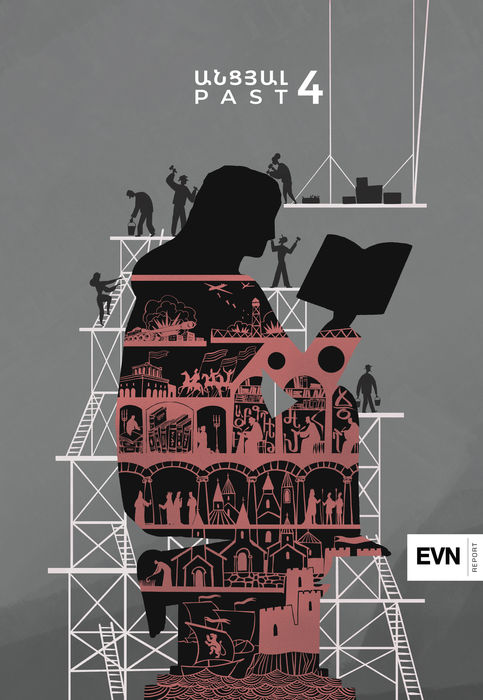

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

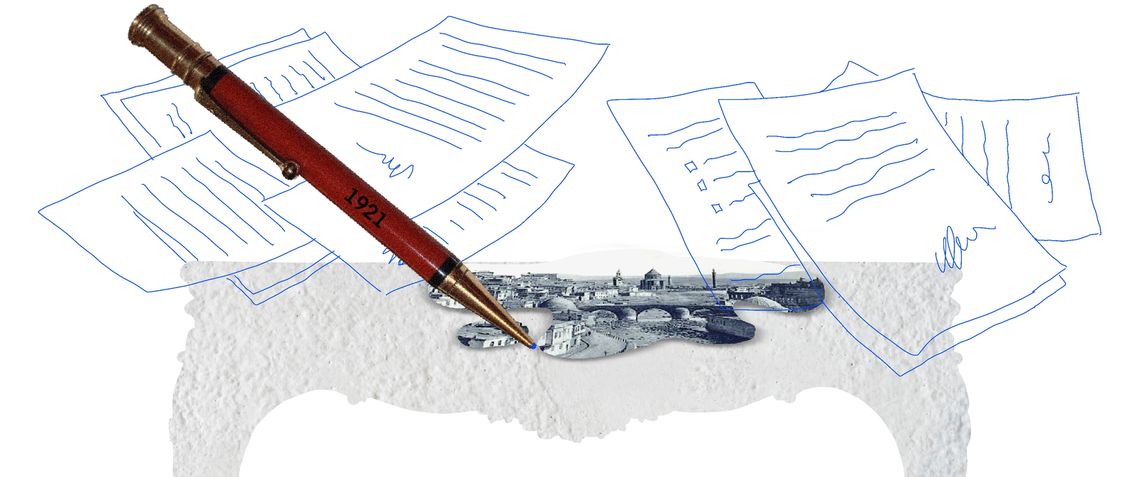

In 1921, both Turkey and Russia were still in the middle of their own civil wars. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s Turkish Grand National Assembly had made major inroads into the Caucasus with its victory in the Turkish-Armenian War of autumn 1920; its armies occupied Alexandropol (today’s Gyumri). The Bolshevik Communists, headquartered in Russia, had taken control of the briefly-independent Transcaucasian republics of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. The three had been Sovietized and the Bolsheviks were looking to consolidate their gains.

The Turkish-Armenian War had come to an end with the Treaty of Alexandropol, through which Armenia had renounced its claim to large swaths of territory that had been under the dominion of the Russian Empire at the start of the First World War, including Kars and Surmalu (where Mount Ararat is found). However, the Treaty of Alexandropol had been signed on December 3, 1920 between the Kemalists and the Democratic Republic of Armenia, which had ceased to exist the day before, with the Sovietization of Armenia. The Treaty of Moscow followed on March 16, 1921, to solidify the friendship between the Kemalists and the Bolsheviks and largely affirmed the border line that had been set by the Treaty of Alexandropol.

While the Treaty of Moscow was signed by the Kemalists and the Bolsheviks, both sides understood that it was also necessary to get the Sovietized Transcaucasian republics to also sign on. Otherwise, the terms may be disputed again at some point in the future. In fact, Article 15 of the Treaty of Moscow obligated Soviet Russia (at this point, the state was called the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, RSFSR) to take steps in this direction:

“Russia is obligated to take certain actions toward the Transcaucasian republics so that the Articles of this Treaty that directly concern them are unconditionally recognized in the agreements to be signed by those republics with Turkey."[1]

Its wording also implied that these further negotiations with Turkey would be based exclusively on the Treaty of Moscow, and no significant changes would be made.

Soviet Armenia Leader Alarmed by Treaty of Moscow

The Treaty of Moscow of March 16, 1921, entrenched such deep territorial losses that even the Armenian Bolsheviks were concerned and tried to explain to their colleagues in Moscow that catastrophic consequences could result from the agreement. After the document was signed, Alexander Bekzadyan, the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of Soviet Armenia, wrote a letter to the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Communist Party of the RSFSR, Joseph Stalin, the People’s Commissar for Nationalities, and Georgiy Chicherin, the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the RSFSR. Bekzadyan noted that, as a result of the Treaty of Moscow, the defense of the Transcaucasus had become very difficult, with Armenia left the most vulnerable. The two most important cities of Armenia, Yerevan and Alexandropol, were no longer at a sufficiently safe distance from the border.

“In the event of a war with Turkey, the defense of these two very important cities has become infeasible. The Turks' possession of the Surmalinsky [Surmalu] district gives them such an advantage that the defense of Yerevan will only be possible from the Kanaker heights,” wrote Bekzadyan.[2] The same fate also awaited Alexandropol; in the event of an attack, it would be necessary to abandon the city and organize resistance in the Jajur mountain pass. The borders drawn by the Treaty of Moscow also posed a threat to the main routes of the Armenian railway: the Yerevan-Alexandropol-Tbilisi rail line ran right along the border. The Turks had been obliged to keep their military bases at least 8 verst (5.3 miles) from the border, but in the event of a war, would be able to cripple the railway infrastructure within a short time. Bekzadyan also drew the Central Committee's attention to the vulnerability of the defense of the other important Transcaucasian cities of Tbilisi and Baku.

One month later, in April 1921, Bekzadyan once again addressed Chicherin, highlighting that disproportionate concessions had been made to Turkey, mainly at the expense of the territories of Armenia. He also drew the attention of the Russian side to the fact that, during the negotiations, Turkey overtly supported Azerbaijan. This Turkish support for Azerbaijan would be enduring.

Chicherin replied to these letters by justifying himself and presenting retaliatory accusations against Bekzadyan. Chicherin noted that the Armenian delegation had had an opportunity to participate in the informal discussions of the Moscow negotiations, where the main points of agreement had been reached. As for the large concessions made to the Turks, according to the Russian People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs, they were not a gift, but rather “the outcome of a long struggle.”[3]

Alexander Bekzadyan would eventually pay a price for raising the alarm. He was soon relieved of his post and replaced by Askanaz Mravyan, who would eventually sign the Treaty of Kars in October 1921.

Turks Prefer Separate Agreements

After the Treaty of Moscow was concluded, the Kemalist delegation was supposed to go to the Transcaucasus to sign separate agreements with the three Soviet republics of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan, confirming with them the agreements already reached in Moscow. Just a week after the Treaty of Moscow was signed, on March 24, 1921, Chicherin, the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of Russia, sent a telegraph to the Bolshevik Central Committee, warning that the Turks might extort additional concessions from the republics.

“The Turkish delegation in Moscow categorically rejected our proposal to convene a joint conference with the delegations of the Caucasus. It is obvious that the Turks want to achieve additional results in Tbilisi, beyond our direct influence,” noted Chicherin.[4] Alexander Bekzadyan also preferred joint participation among the three republics in their negotiations with Turkey; he appealed to the representatives of Georgia and Azerbaijan to take this route. In April 1921, the Turkish delegates tried to reach separate agreements with Georgia and Azerbaijan in Tbilisi and Baku respectively, but failed to do so. The issue of convening a joint conference thus was on the table, though, up until September, the Turkish side tried regularly to advance the thesis of concluding separate agreements with the three Transcaucasian republics rather than a common one.

To apply pressure, the Turks were deliberately delaying their withdrawal from Alexandropol, although the Treaty of Moscow required it. Kazim Karabekir, the Commander of the Eastern Front for the Turkish Grand National Assembly who had led the victory against the Democratic Republic of Armenia, wanted to hold off the withdrawal from Alexandropol until an agreement with Soviet Armenia was concluded. On April 8, 1921, Chicherin sent a letter of protest to Ali Fouad, the Turkish Ambassador in Moscow, stating that Turkish troops must withdraw from Alexandropol immediately. Chicherin's telegram was in answer to a statement by Kemal Fevzi, the Turkish Defense Minister, that the Kemalist army should “play the role of a balancing element” in the Caucasus. Chicherin warned that they viewed these actions as hostile. His note read:

“In the same statement, the Defense Minister says that the part of Armenia that is still under the occupation of Turkish troops will be evacuated only after the Alexandropol agreement is implemented. I would like to remind you that the Treaty of Alexandropol was signed by the ARF government at a time when the Soviet government of Armenia had already been proclaimed, and that it is not ratified. According to that treaty, the condition for its entry into force was ratification within a month.”[5]

On the same day, Chicherin telegraphed Sergo Ordzhonikidze, the Chairman of the Bolshevik Caucasus Bureau, mentioning that it was necessary to immediately implement the provisions of the Treaty of Moscow and liberate Alexandropol from the Turks.[6] Only after these vigorous protests from Soviet Russia did the Turkish troops completely withdraw their troops on April 22, 1921, as the Treaty of Moscow required.

The Transcaucasus Republics Try to Develop a Common Position

While the Turkish side was trying to sign separate agreements with the Transcaucasian republics, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan had to present their final position on this issue. For this purpose, on May 7, 1921, a meeting was held in Baku between the representatives of the three republics. Alexander Bekzadyan represented Armenia. Mamia Orakhelashvili, Secretary of the Georgian Bolshevik Central Committee, represented Georgia. Azerbaijan was represented by Mirza Davud Huseynov, the People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Soviet Azerbaijan, and Behbud Shahtakhtinski, the People’s Commissar for State Control of Soviet Azerbaijan. Taking into account the importance of the conference, Sergo Ordzhonikidze and Boris Legrand, the representative of the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (RSFSR) in the Transcaucasian republics, were also present.

The bases and format of the negotiations between the Transcaucasian republics and Turkey were discussed at the conference. It is here that it was decided that the three republics would participate jointly in the negotiations with Turkey, as one side to the agreement. It was also decided that the Treaty of Moscow would serve as the anchor to the new agreement. A separate point defined the principle of normalization of relations between Armenia and Turkey:

“Taking into account that the issues related to the establishment of contractual relations by Turkey are particularly acute, the conference decided to insist that, at the forthcoming conference, of all the issues related to the establishment of contractual relations, the first to be discussed will be between Turkey and Armenia, then the second with Georgia and the third with Azerbaijan.”[7]

During this meeting of the representatives of the Transcaucasian republics in Baku, it was also decided to develop draft agreements with Turkey. Prior to that, the plenum of the Bolshevik Central Committee had decided that the Soviet republics of the Transcaucasus should submit versions of possible agreements with Turkey to the Central Committee for approval.[8]

Chicherin was also concerned about the relations between Azerbaijan and Turkey, which could potentially jeopardize Russia's interests in the Transcaucasus and undermine the Sovietization of the three republics. Huseynov had also reported to Chicherin on the special attitude of the Turks toward Azerbaijan. On April 18, 1921, he telegraphed to Moscow that Mahmoud Shevket, the Turkish diplomatic representative in Azerbaijan, had offered to convene a separate Turkish-Azerbaijani conference. Huseynov had replied to him that they cannot establish separate relations with Turkey, and that the Transcaucasian republics would act together on a number of issues. He wrote to Chicherin:

“Noting the common interests and goals of the Soviet countries, I informed him that the unification of the Transcaucasian republics has been initiated, with the establishment of a joint Transcaucasian Railways Department, a union of foreign trade, and a joint economic council of all the Transcaucasian republics. Therefore, I informed Mahmoud Shevket that the Transcaucasian republics must sign an agreement with Turkey together.”[9]

Mahmoud Shevket had announced that their delegation had been authorized to sign separate agreements only with Azerbaijan and Georgia. On July 14, 1921, Sergey Natsarenus, the representative of the Russian Bolsheviks in Angora [today’s Ankara], telegraphed Chicherin that Yusuf Kemal, the Turkish Foreign Minister, had sent an invitation to Georgia and Azerbaijan to participate in the conference. Armenia’s invitation was sent via Azerbaijan.[10] The Turkish side wanted to hold the conference in Angora. The Turks gave in due to Natsarenus' efforts to ensure a Russian representative would also participate, but they stated that the Russian representative should not be Legrand, who “in the opinion of the Turks, sympathized with the Armenians.” Natsarenus was the most suitable candidate for the Kemalists. The Russian Bolsheviks agreed to send Natsarenus and also Yakov Ganetsky, the Russian Bolshevik representative in Latvia, to the negotiations.

After long discussions, Yusuf Kemal had agreed to hold the conference in Sarikamish; Natsarenus announced that he was trying to get consent to hold one in Kars as well. On August 27, it was agreed that the conference would take place in Kars at the end of September. It should also be noted that, despite various interpretations and diplomatic maneuvers, the Turks always insisted that, no matter what, the negotiations should be based on the Treaty of Moscow.

Turkey Does Not Invite Armenia

Since the conference was to be held in Turkey, the Turkish side had to send an invitation to the Transcaucasian republics. In July 1921, both Azerbaijan and Georgia received Kazim Karabekir’s official invitation. However, Karabekir did not issue an invitation to Armenia, noting that Armenia itself should apply and express a desire to participate in the conference. The Turkish side tried to justify this decision by invoking the Treaty of Alexandropol of December 2, 1920. However, that treaty had no legal basis; neither Armenia nor Turkey had ratified it. In order for the agreements, which were reached with great difficulty, not to fall through, Chicherin asked Armenia to send such a note to Turkey. On August 24, 1921, Askanaz Mravyan, the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of Soviet Armenia, sent an official application to Yusuf Kemal, the Kemalist Foreign Affairs Minister. Mravyan's official letter read:[11]

“In order to finally normalize the relations between Armenia and Turkey on a contractual basis, Soviet Armenia expresses a desire to participate in the forthcoming Turkish-Transcaucasian conference with the participation of the representative of the RSFSR. The government of Soviet Armenia hopes that the government of the Turkish Grand National Assembly will give its consent.”

According to Mravyan, on the one hand, all issues should have been discussed in the negotiations with Turkey and on the other with the representatives of the Transcaucasian republics and Soviet Russia.

“The revolutionary governments of the Soviet proletariat and the Turkish Grand National Assembly, freed from the obtuse chauvinism and mutual hatred of their predecessors, will be able to find a just solution to all issues and settle the centuries-old struggle and hatred of neighboring peoples, which has been skillfully and maliciously instigated by imperialist diplomacy.”[12]

A few days later, the consent of the Turkish side was received.

The Hopes of the Armenians

Once the place, time and structure of the conference had been finalized, the Armenian authorities began to prepare. Similar to the time period leading up to the Moscow conference, there was hope that, as a result of the negotiations, it would be possible to mitigate as much as possible the consequences of the catastrophic agreements, and change some economic and political provisions in favor of Armenia. For that purpose, a session of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia was convened in Yerevan on August 26, 1921. The demands of the Armenian side were discussed and summarized in a memorandum. The political section of the document stated that it was necessary to make border adjustments in the Surmalu region, referring mainly to the areas of Koghb that were rich in salt mines. The Armenian side was hopeful this part would pass to Soviet Armenia, despite the Treaty of Moscow, because “Koghb is the only place from where Armenia can get salt without special means necessary for exploitation. Salt is the only currency commodity in the territory of Armenia that can enable the exchange of foreign goods.”[13]

The memorandum stated that, by creating the Nakhichevan region and handing it over to Azerbaijan, Armenia was losing its road connection with Syunik and Vayots Dzor, as well as Iran. The other territorial claim referred to the Arpa neutral zone, which the Armenians hoped to “expand and introduce a mixed Armenian-Turkish administration there.” Although the wording of the memorandum was not specific, in all probability, the Armenian side was referring to the ruins of the city of Ani.[14]

As for the economic component, the Armenian side hoped that, as a result of the negotiations and by making appropriate payments to Turkey, it would get the right to exploit the coal mines of Olti and arsenic deposits in Kaghzvan. Managing the Surmalu forest was also of great importance for Armenia, as “it was the only building material for Armenia.” [15] The Armenian side offered to help organize the protection of the forest through joint efforts.

Clarification of Positions

While details of the negotiations with the Turks were being discussed in Armenia, Moscow, in turn, was clarifying its position for the Kars conference. The plenum of the Russian Bolshevik Caucasus Bureau took place on September 3-4, 1921, to finalize what issues should be discussed at the Kars conference, and how. The plenum decided that negotiations should take place exclusively within the framework of the Treaty of Moscow, and the Transcaucasian republics should show their solidarity with Angora against the Entente [Britain, France and the Tsarist White Army]. The Caucasus Bureau decided, “Under no circumstances should any Caucasian republic be permitted [to speak against the others]. There should be unanimity on all issues.”[16]

A few days later, Chicherin related these positions to Natsarenus, the Plenipotentiary Representative of the RSFSR in Angora. Chicherin wrote: “The Transcaucasian republics must sign an agreement, strictly following the Treaty of Moscow, not allowing our friends to make more concessions to the Turks than we have already made. On the other hand, the difficult situation of the Turks should not be used to harm them. The position must be decisive. The decisions of the Moscow conference remain in force."

Two Crates of Brandy, Two Crates of Wine, Three Pounds of Tea

The Kars conference commenced on September 26, 1921. Armenia was represented by Askanaz Mravyan and Poghos Makintsyan, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs. Azerbaijan was represented by Behbud Shahtakhtinski. Georgia was represented by Shalva Eliava, People's Commissar for Military and Maritime Affairs, and Alexander Svanidze, People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs.

The first official session of the conference was opened by Kazim Karabekir. The negotiations were also attended by Veli Bey, a member of the Turkish Grand National Assembly, Mukhtar Bey, Assistant Secretary of State, and Mahmoud Shevket, the Turkish diplomatic representative in Azerbaijan.

At the request of the Department of Foreign Affairs, the People's Commissar for Food of Soviet Armenia issued some provisions for the needs of the Armenian delegation to Kars, including “boxes of brandy and wine (two of each), 3 pounds of tea, two boxes of canned food and 20 pounds of sugar.”[17]

The Kars conference held six full and nine informal sessions. Yakov Ganetsky, the representative of the Russian Bolsheviks was the main negotiator and head of the Russian delegation. In Kars, the Turkish side once again tried to push forward the concept of signing separate agreements with each of the Transcaucasian republics; they were once again unsuccessful. Early in the negotiations, Ganetsky presented the proposal of handing over the ruins of the city of Ani to Soviet Armenia. At first, it seemed like the Turks might agree. On September 29, Mravyan sent a telegram to Alexander Myasnikyan, the Chairman of the People's Council of Soviet Armenia, saying that they had already raised the issue of Ani. “The Turks will most probably agree… They have a big appetite, which is gradually becoming political,”[18] he wrote. Gradually, however, the Turkish position started to harden, until they sharply rejected the proposal on the grounds that it would be a deviation from the Treaty of Moscow. “From a military point of view, this issue is of great importance for us. However, we also acknowledge that it has a great historical and cultural significance for Armenia and announce that… the historical and cultural significance of that region will be preserved. There is no need to change the border and deviate from the Treaty of Moscow.” Such was the response of the Turkish delegation.

The Turks also rejected all the economic proposals regarding Surmalu, Olti and Koghb, arguing that these were commercial issues that could be settled later.

The final version of the treaty was signed on October 13. Under the first article, the parties renounced all international treaties previously negotiated between the parties, except the 1921 Treaty of Moscow. Under Article 5, the Turkish government and the governments of Azerbaijan and Armenia agreed that the Nakhichevan province should be an autonomous territory under the auspices of Azerbaijan. The parties undertook to release all prisoners of war—both military and civilian—within two months of the signing.

* * *

Hence, the attempts of the Armenian side to mitigate the harsh provisions of the Treaty of Moscow ultimately failed. Armenian diplomacy did not succeed in Kars. Albeit, it is a stretch to say that the Armenian side was an independent negotiator, especially when, according to experts, the Armenian delegation did not express any complaints or objections throughout the negotiations.

The Treaty of Kars was signed under difficult geopolitical conditions. Turkey was able to use the “threat” of normalizing its relations with the West to extract maximum concessions from the Russian side, mainly at the expense of Armenia. It is worth remembering that these capitulations by the Soviet Armenian authorities were made in the aftermath of the 1920 Turkish-Armenian War, in which it had suffered a decisive defeat.

----------------------

[1] Armenia in international diplomatic and Soviet foreign affairs/policy documents, Yerevan, 1972, p. 504

[2] Yu.G. Barsegov, Armenian Genocide. Turkey's Responsibility and the Commitment of the World Community, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 463. Source: http://genocide.ru/lib/barseghov/responsibility/v2-1/1132-1162.htm#1141

[3] Ibid, p. 499. Source: http://genocide.ru/lib/barseghov/responsibility/v2-1/1163-1199.htm#1183

[4] Ararat Hakobyan, “Soviet Armenia in the Treaties of Moscow and Kars,” Yerevan, 2010, p. 219

[5] Armenia in international diplomatic and Soviet foreign affairs/policy documents, Yerevan, 1972, p. 509

[6] Ibid, p.510

[7] “On Lenin’s Path”, 1965, No 2, pp. 84-85

[8] Yu.G. Barsegov, Armenian Genocide. Turkey's Responsibility and the Commitment of the World Community, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 482

9. Armenia in international diplomatic and Soviet foreign affairs/policy documents, Yerevan, 1972, p. 511

[10] Yu.G. Barsegov, Armenian Genocide. Turkey's Responsibility and the Commitment of the World Community, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 513. Source: http://genocide.ru/lib/barseghov/responsibility/v2-1/1200-1228.htm#1203

[11] Ararat Hakobyan, “Soviet Armenia in the Treaties of Moscow and Kars,” Yerevan, 2010, p. 249

[12] Armenian National Archives, Fund 113, List 3, Folder 23, p. 25

[13] Armenian National Archives, Fund 113, List 3, Folder 23, p. 97

[14] Ararat Hakobyan, “Soviet Armenia in the Treaties of Moscow and Kars,” Yerevan, 2010, p. 250

[15] Ararat Hakobyan, “Soviet Armenia in the Treaties of Moscow and Kars,” Yerevan, 2010, p. 252

[16] Armenian National Archives, Fund 114, List 1, Folder 172, pp. 8-9

[17] Armenian National Archives, Fund 113, List 3, Folder 23, p. 54

[18] Armenian National Archives, Fund 113, List 3, Folder 21, p. 3

Past | Issue N4

Does history repeat itself? Recent events have served as a catalyst to discuss and ponder the lessons that might be drawn from history. Under the careful curation of historian and guest editor Suren Manukyan, the February 2021 issue delves into the past to try and understand the present.

History and Us

By Suren Manukyan

The past never leaves us, it casts a long shadow, influences thoughts, opinions, decisions and actions but never really repeats itself, writes historian Suren Manukyan, guest editor for this month’s issue titled “Past.”

From a Fateful Revolution to the Dream of Pan-Turkism: Causes of the Armenian Genocide

By Suren Manukyan

Turkey continues to fight against the recognition of the Armenian Genocide through falsification of history, anti-Armenian propaganda, using all political, economic and lobbying levers at its disposal.

The Fall of Kars: A Look to the Past

By Mikael Yalanuzyan

Armenia’s defeat and the loss of land in Artsakh took place exactly 100 years after the Turkish-Armenian War of 1920. Armenian society started drawing parallels between the fortress cities of Kars and Shushi.

Attempts to Restore Statehood and Armenia’s Last Crowned King

By Smbat Hovhannisyan

Following the fall of the Kingdom of Cilicia in the 14th century, attempts were made to restore the Armenian Kingdom with Smbat Sefedinian-Artsruni, the last crowned king of the Armenian people.

The Pearl of the Mediterranean: Cilician Armenia at the Crossroads of East-West Trade

By Zohrab Gevorgyan

The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia consolidated and synthesized cultures, giving new breath to the traditional, by creating a new, more complete Armenianness. Surviving for 300 years demanded tremendous civilizational potential from the Armenian people.

Conversion to Christianity and the Creation of the Armenian Alphabet

By Shavarsh Azatyan

The secular, religious and cultural elites of what became Armenia’s Golden Age were able to turn challenges into a stimulus, setting in stone the Armenians' mark over their territory that would last for centuries.

New on EVN Report

Genomics and Bioinformatics: Challenges and Opportunities

By Lilit Nersisyan

Academic programs around the world are not preparing enough bioinformaticians to deal with the exponential data growth we are observing. Armenia needs to catch up quickly.

The 2022 State Budget

By Suren Parsyan

Will the 2022 state budget be able to solve or alleviate the socio-economic and security problems Armenia is facing?

The Multilayered Causes of the War

By Tigran Grigoryan

A unique combination of causal factors at different levels made the 44-day war possible. Tigran Grigoryan presents a systematic and comprehensive explanation of the structural conditions and circumstances behind Azerbaijan’s large-scale offensive.

Municipal Elections Bring Prospects of Coalition-Building

By Harout Manougian

Residents in six municipalities across three of Armenia’s regions (Syunik, Tavush and Shirak) went to the polls on October 17, 2021. Municipal elections will continue this fall in several other regions. Harout Manougian explains.

The All Armenian Fund: Donors Still Waiting for the Audit

By Raffi Elliott

Controversy erupted after the Hayastan All Armenian Fund transferred 60% of funds donated during and after the war to the state budget. The absence of a complete audit almost a year since it was first proposed leaves donors still asking “where is the money?”