Though I have observed elections in several different countries, I have never experienced the same emotions as when I watched Stepanakert residents shuffle into the Charles Aznavour Cultural Center to cast their vote for mayor and city council on September 8. It is common to hear about those who made sacrifices to guarantee the freedoms of their community but never before had I witnessed it firsthand in such a raw manifestation. Rays of joy and pangs of grief mixed together as I saw mothers who had lost their sons, young people who had lost a parent, and veterans bearing scars, both visible and invisible, pay the highest form of respect to the sacrifices that continue to be made in their name: exercising their hard-won right to vote and getting a say over their own future.

That understanding was especially evident among Stepanakert’s youth. With the election taking place on a Sunday, one young woman lined up to vote right as the polls opened at 8:00 a.m., as she needed to travel to Yerevan, where she currently studies, for class the next day. Another young woman came in to vote on her wedding day, still wearing her bridal gown. In fact, 17 of Stepanakert’s 42 city council candidates were under 30.

Strategic Importance of Artsakh’s Elections

Most international organizations that conduct election observation missions are prevented from stepping foot in Artsakh. Their funding comes from the budgets of governments that have not recognized the Artsakh Republic. Nevertheless, individual politicians and public figures from countries including Russia, the United States, France, Canada, Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Argentina, Estonia and Cyprus, on their own accord, have come as election observers in the past. In response, the Azerbaijani Foreign Affairs Ministry typically adds them to a blacklist, prohibiting them from visiting Azerbaijan in the future. You can’t blame them for trying to discourage the practice. In contrast to Artsakh’s open elections, Azerbaijan is essentially a hereditary dictatorship, where the President succeeded his father, abolished term limits and installed his wife as Vice-President. Bringing attention to the stark difference in civil freedoms between the two would heavily favor the Artsakh side in the ultimate resolution of the conflict.[1]

In the absence of international monitors, the Armenian government stepped in to fund two separate observation missions. The Artsakh branch of the Union of Informed Citizens (UIC) was allocated the equivalent of $34,100 USD and Transparency International’s Yerevan affiliate (officially named Transparency International Anticorruption Center, or TIAC) received $36,800 USD. Both organizations have experience conducting large-scale election observation projects in Armenia, including pursuing violations in court. TIAC had also participated in the public comment period in a recent round of amendments to Artsakh’s Electoral Code. A delegation of MPs from all three parties, from Armenia’s National Assembly as well as representatives of Armenia’s Central Election Commission also conducted their own observation missions.

Observations of Note

I participated as an observer in TIAC’s mission, which teamed up with an Artsakh-based organization called Civic Hub to pair up local observers holding Artsakh citizenship with an experienced partner that had observed an election in Armenia in the previous two years. The partnership, operating under the name “Witness Observer” doubled as a training exercise to build local capacity among Artsakh residents interested in learning the intricate details of their Electoral Code and how to verify that they are being followed correctly. In total, our mission encompassed 103 observers stationed across 40 polling locations for the full day, with the rest circulating across multiple locations throughout the day. Every region of Artsakh was covered, with the focus on polls with over 300 voters.

In a post-election press conference, Sona Ayvazyan, Executive Director of TIAC, concluded that the few instances of deviations from the Electoral Code were mostly technical in nature, not premeditated by election staff, and corrected immediately upon the issue being raised. For example, arriving at my poll at 7:00 AM, I noticed that the building’s security camera was positioned behind the voting screens. I brought the concern to the attention of the local election commission supervisor, requesting that the voting screens be moved to a different section of the room. Though, the security camera was reportedly not working at the time, the supervisor agreed its placement was inappropriate and got the building custodian to remove it – by removing the entire ceiling tile that it was attached to.

Two other technical issues at my poll had to do with the administrative documentation of accessibility accommodations. As most voting locations are not wheelchair accessible (only 25 percent of the sites visited by TIAC observers were), Artsakh’s Electoral Code includes a special provision for wheelchair-bound voters. The special protocol was used once at my poll: upon checking the voter’s identification, the ballot was brought out to him to fill out in his vehicle (it was raining lightly at the time), after which the folded ballot was brought back inside and dropped into the ballot box by the poll supervisor. I had to remind the poll supervisor that, according to the rules, he then needed to write the word “wheelchair” next to the voter’s name on the voters’ list. After reviewing the relevant section of the Electoral Code, he immediately complied.

The other accessibility accommodation is that, as in Armenia, Artsakh voters may request that someone assist them in filling out the ballot behind the voting screen. This approach is meant as a last resort for the visually impaired or amputees. It can be used by older citizens upon their request, with no questions asked. Depending on where in the Soviet Union they grew up, some older Artsakh residents were not taught the Armenian alphabet in school but the ballot is printed only in Armenian. In many cases, the poll supervisor offered his own personal eyeglasses to the voter and that was sufficient. In others (14 of the 580 voters at my poll), a random voter waiting in line was asked to assist them behind the voting screen. Each person is only allowed to help one other voter. When the first such case arose at my location, I had to remind the poll secretary that the names and ID numbers of the helpers needed to be recorded in the poll register. Upon finding the appropriate page, she diligently followed the protocol.

In terms of design, the long ballot paper for Stepanakert city council, containing 42 names, was not compatible with the voting screens that were used, which had a gap between the flat surface and the back panel, allowing the top of the ballot to peek out the back if the voter was not careful. Concerns like this one will be included in the final reports of the observation missions to the Central Election Commission as part of a list of recommendations to improve the overall voter experience. With Artsakh’s presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled to take place in 2020, lessons learned can be used to refine the process for next year’s iteration.

Not Everyone Was Happy

There was at least one person who was suspicious of the observation missions, however. Vitali Balasanyan, an Artsakh war hero, former secretary of the National Security Council and potential 2020 presidential candidate, referred to them as “direct interference with the sovereignty and Constitution of Artsakh.” In response, Sona Ayvazyan pointed out that they were participating on the invitation of Artsakh’s Central Election Commission and required to be strictly neutral throughout the process. For his part, Masis Mayilyan, Artsakh’s Foreign Affairs Minister, welcomed the observers, mentioning that their participation contributed to “the acquisition of modern experience.” Mayilyan is also seen as a potential 2020 presidential candidate.

Stepanakert Election Results

All 228 communities in Artsakh held their municipal elections on September 8, electing both a mayor and members of city council.[2] Stepanakert had five candidates for mayor and 42 candidates for 15 available city councillor positions, all elected at-large. Voters could select one candidate for mayor and one candidate for city council. The two races received their own ballot papers, of different sizes and colors, which both went into the same ballot box. Due to the large size of the city council ballot paper, which had to be folded several times to fit into the opening, the ballot box at my poll was physically filling up very quickly. They eventually brought in a second official box to handle all the paper.

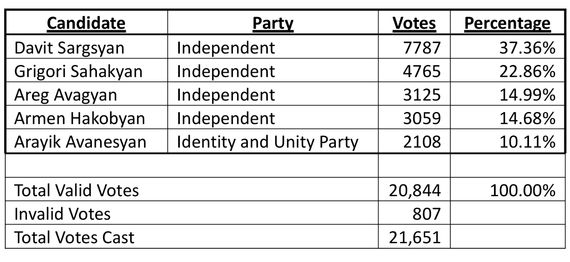

At the end of the night, the results for mayor were as follows:

Similar to most North American elections, only a plurality of votes is necessary to be elected. That is, the winner does not need to collect more than 50 percent of the votes cast, only more than the other candidates. Thus, with 37 percent support, Sargsyan was elected the winner. There is no run-off between the top two candidates. Sahakyan, a former army base commander, who came in second, though running as an independent, had been endorsed by both the Sasna Tsrer Party and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF).

For a vote to count, it needs to have a “v”-shape (or checkmark) in the appropriate box next to the candidate’s name. Any other mark could be seen as a way to make the ballot paper uniquely identifiable and renders the ballot invalid. My poll had 24 invalid ballots (4 percent of our 580 total) for the mayor’s race, including one paper that wrote in “Henrikh Mkhitaryan,” the captain of Armenia’s national soccer team.

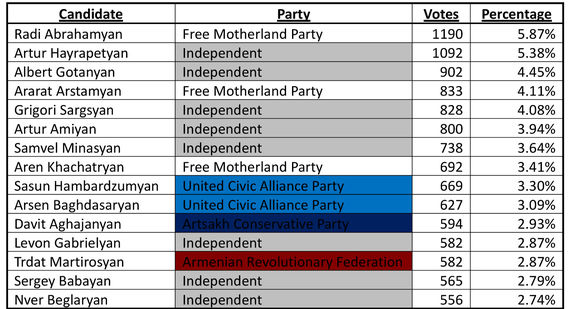

A non-scientific poll conducted by Artsakhpress between August 15 and September 6 had pegged Sargsyan as the frontrunner in the race, albeit by a much wider margin. The poll’s results, limited to a non-random sample size of 291 was way off when it came to the city council race, though. The actual election results are shown below:

Electoral System Considerations

Each voter received a voter information card, hand-delivered to their door, informing them of the date of the election, which poll they were eligible to vote, and the hours it would be open. It also included their order on the voters’ list, making it easy for the poll workers to look them up. Our location had two different polls in the same building, with their entrances right next to each other. The voter information card made it very easy to redirect them when they came in the wrong entrance.

Holding multiple elections at the same time can lead to a voter having more information about a higher-profile race and be less informed about a “down-ballot” race. Most Stepanakert voters probably knew which mayoral candidate they wanted to vote for when they entered the polling location. However, the fact that Radi Abrahamyan’s name appeared first among the alphabetically-ordered 42 council candidates on the ballot and that he also received the most votes cannot be attributed to mere coincidence. Research shows that the impact of ballot order (the advantage received by being listed first) is highest in non-partisan, down-ballot races without an incumbent. Though party membership of the candidates is shown in the table above, on the ballot itself, only the Communist Party and United Civic Alliance Party candidates were listed as being nominated by their party. All other candidates were listed as self-nominated on the ballot, as they filed their own registration paperwork. In some jurisdictions of Australia (which has mandatory voting) and the United States (which holds elections for multiple positions on the same day), the names on the ballot are rotated to minimize this effect.

The system used for the city council race in Stepanakert, where multiple candidates are elected from the same area and each voter gets to choose only one is referred to in academic literature as Single Non-Transferable Vote (SNTV). It is simple to explain and tabulate but makes life difficult for political parties. In this case, the United Civic Alliance Party, founded in September 2018 by Artsakh youth inspired by Armenia’s Velvet Revolution, played the system perfectly. With two members (ages 25 and 28) nominated, receiving roughly the same number of votes, they were both in the top 15 and got elected. Had a third party member been nominated, vote splitting could have resulted in none of them getting through. Likewise, if supporters of the party concentrated too many votes on only of the two candidates, the other one would not have been elected. In Japan, which has extensive experience with this system, party supporters are instructed to vote for specific candidates based on their address, to optimize the number of members elected.

On the other hand, neither of the Independence Generation Party candidates were elected. If only five of Rafik Hovhannesyan’s voters had chosen his colleague Arayik Tsatryan instead, they could have had at least one representative on the council, instead of zero. In the same vein, if only two Armenian Revolutionary Federation members ran instead of three, it is conceivable that they could have both gotten in. One last example is that both Sonya Hambardzumyan and Nune Petunts were female candidates from the Free Motherland Party. Their combined vote total would have been enough to place in the top 15 but, running separately, neither was elected. In fact, no women were elected in Stepanakert’s municipal election this year.

The party-centric proportional system used for municipal elections in Yerevan, Gyumri and Vanadzor takes the opposite approach. Though not friendly to independent candidates, by presenting pre-determined party lists for voters to choose from, they don’t need to concern themselves with how potential vote splits might play out. These cities also do not hold a separate mayoral election. The mayoral candidate of the majority party in the city council gets to take office. Thus, the mayoral candidates of the other parties still get a council seat and remain active in the municipal political scene. In Stepanakert, though the four losing mayoral candidates received several times more votes than the most popular elected council member, they will have no official role in decision-making at the city level for the next five years.

The national parliamentary elections scheduled for Artsakh in 2020 will use the party-list system, which also includes a gender quota, requiring at least every fourth name on a party’s list to be a female candidate. It will take place together with the presidential election; so, once again, Artsakh voters will be filling out two ballots on the same day.

--------------------------

1- In its assessment of Azerbaijan’s 2018 presidential election, the OSCE ODIHR concluded, “the election took place within a restrictive political environment and under a legal framework that curtails fundamental rights and freedoms, which are prerequisites for genuine democratic elections. Against this background and in the absence of pluralism, including in the media, this election lacked genuine competition. Other candidates refrained from directly challenging or criticizing the incumbent, and distinction was not made between his campaign and official activities.” It goes on to mention, “On election day, international observers reported widespread disregard for mandatory procedures, lack of transparency, and numerous serious irregularities, such as ballot box stuffing."

2- Note: The literal translation of the Armenian term for city council is Council of Elders.

also read

Armenia and Artsakh: A Tale of Two Electoral Reforms

By Harout Manougian

Electoral Code reform has been on the agenda in Armenia following the Velvet Revolution last year and the Republic of Artsakh just enacted amendments to its Electoral Code as it prepares for national elections in 2020. Harout Manougian looks at the situation in both republics.

Returning From the Line

By Anna Astvatsaturian Turcotte

What is it like to find yourself on a heavily militarized contact line? How does it feel to see an adversary, a mere 400 meters away, who was the reason you became a refugee? Anna Astvatsaturian Turcotte, a refugee from Baku, writes about her emotional journey to the line and back.

Taking Up the Challenge of Peace

By Armine Aleksanyan

Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister of Artsakh, Armine Aleksanyan on her long journey from Martouni to Stepanakert, to London and Vienna and back to Artsakh to work in the service of a country that is not recognized by the world

The Spirit of Artsakh

By Scout Tufankjian , Maria Titizian

Photographer Scout Tufankjian has captured the essence of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh) through her photos. One year after the April War, EVN Report is proud to present these images as a reminder that all children deserve to live in peace.

We are pleased to open up a comments section. We look forward to hearing from you and wish to remind you to please follow our community guidelines:

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments on Readers' Forum will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.