Thu Aug 01 2019 · 9 min read

Armenia and Artsakh: A Tale of Two Electoral Reforms

By Harout Manougian

Both Armenia and Artsakh are making changes to their Electoral Code in 2019. Artsakh is preparing for its 2020 parliamentary and presidential election, the first since its 2017 constitutional referendum. Under the new presidential model, the role of Prime Minister has been eliminated and the election of Artsakh’s next President and Parliament will take place on the same day. Local, municipal-level elections are also scheduled for Artsakh on September 8, 2019.

In Armenia, the National Assembly is picking up a process that started last summer when Nikol Pashinyan announced that snap elections would take place as soon as the Electoral Code was amended.

Background on Armenia’s 2018 Electoral Reform Effort

The work of those committees resulted in a bill being brought to a vote in Parliament that, among other changes, would have:

-

Eliminated the open list (ratingayin) component of the election

-

Lowered the threshold to enter Parliament to 4 percent for single parties and 6 percent for alliances of multiple parties (from 5 percent and 7 percent respectively)

-

Allowed the fourth place party to enter Parliament with a lower 2 percent threshold

-

Raised the gender quota to require at least every third name on the national closed party list to be a female candidate (raised from at least every fourth name)

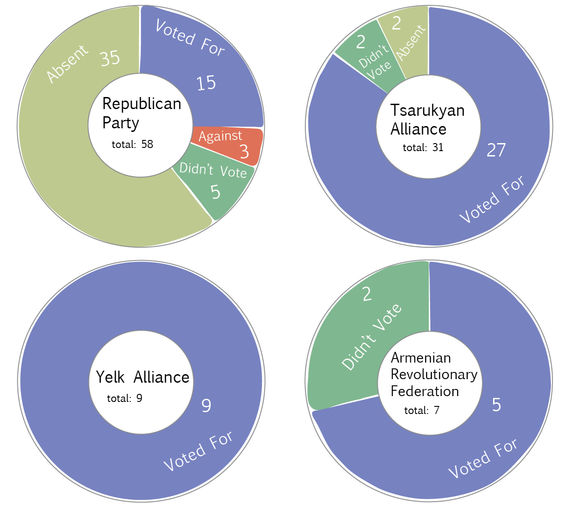

The bill was voted on during the October 22, 2018 sitting of the National Assembly. Though a majority of MPs voted in favour of the bill and only three MPs (Republican Party members Ara Babloyan, Armen Ashotyan, and Khosrov Harutyunyan) voted against it, changes to the Electoral Code require affirmative votes from at least 60 percent of Parliament. Receiving only 56 votes in favor, the bill fell short of the required 63 out of the 105 Members of Parliament at the time. It became clear that the Republican caucus had effectively used a pocket veto by not showing up to the legislative session so that the bill would not pass.

Voting Record from October 22, 2018 on Electoral Reform Bill

The manoeuvre was denounced by Nikol Pashinyan and Tsarukyan Alliance MP Naira Zohrabyan as “sabotage” by the Republican caucus. Armen Ashotyan argued that, with new elections already set to take place by the end of the year, there was not enough time to implement the changes within two months.

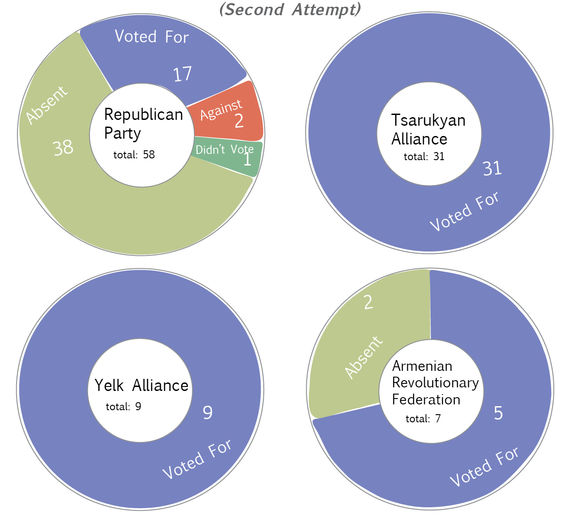

The bill was brought back to Parliament a week later for a second vote. This time, under even more media scrutiny and political pressure, it fell only one vote short of passing, though only two MPs (Republican Party members Arpine Hovhannisyan and Armen Ashotyan) bothered to vote against it.

Voting Record from October 29, 2018 on Electoral Reform

The vote carried significant consequences for the ensuing December 9 election. None of the MPs who voted against, abstained, or were absent that day were re-elected. As karma would have it, the Republican Party received 4.7 percent of the vote, just shy of the original 5 percent threshold. They did not qualify for any seats after the election but would have under the proposed amendments that they blocked, which aimed to both lower that threshold to 4 percent and give a waiver to the threshold for the fourth-place party, which turned out to be the Republicans. One could also speculate that the ARF, which received 3.9 percent of the popular vote on December 9, could have attracted the additional 1500 votes they needed to get to 4 percent if they ensured perfect attendance on October 29, as both the Tsarukyan and Yelk Alliances were able to achieve. Either one of their two absent members could have caused the electoral reform package to pass.

Armenia Renews Electoral Reform Effort in 2019

Now, in the summer of 2019, all that drama feels like ancient history but it is important background to the current, renewed effort at electoral reform in Armenia. In the new, My Step-dominated Armenian legislature, electoral reform is still on the agenda but the discussions to date have been less formal.

On March 6, 2019, Ararat Mirzoyan, the Speaker of the National Assembly, announced that the process would be restarted. A new Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform was formed; though, instead of assigning each party a specific number of seats at the table, its sessions are open to any interested Member of Parliament. It has met on two occasions for informal discussions: the first was a Brainstorming Workshop led by the Armenia office of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) on June 8 and 9. The second was a discussion on July 10 with a delegation from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE ODIHR) on the regulation of money in politics. Indeed, the participation of international organizations in the electoral reform process is one area in which Armenia and Artsakh differ greatly. The National Democratic Institute (NDI), the International Republican Institute (IRI), and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) have also initiated major projects to assist in the development of Armenia’s democratic system by facilitating public consultation standards and providing training to members of the Central Election Commission.

Artsakh’s 2019 Electoral Reform

However, none of these organizations participated in the electoral reform deliberations that have already been completed in Artsakh. The bill was introduced for its first reading on June 27, 2019 and passed in its final version less than a month later on July 22, with 26 votes in favor and 4 against. Three MPs from the Movement 88 Party and one former member - now independent - of the Free Motherland Party voted against the bill. The signature change was the elimination of the de facto republic’s 11 electoral districts. Currently, 11 of Artsakh’s 33 Members of Parliament are elected in single-member districts. The other 22 seats are awarded proportionally to political parties based on their closed national party list. Each voter would cast two separate ballots, one for their local district representative and one for their preferred national party (which could have been a different party than the one their preferred local candidate belonged to). The proportional (or hamamasnakan) seats are awarded separately from how the district (or medzamasnakan) seats play out. In academic literature, this approach is called a parallel mixed electoral system or sometimes also Mixed Member Majoritarian (MMM), which is common in many Soviet Union successor states.

With the recent changes, the total number of parliamentarians will remain at 33, but they will all be selected off the parties’ national lists, moving Artsakh to a full Proportional Representation (PR) electoral system. In order to qualify for any seats, a political party will have to receive at least 5 percent of the popular vote. If multiple parties join forces to present one, unified list, that minimum threshold is higher at 7 percent (these are the same levels currently in force in Armenia).

Before the electoral reform bill passed, the previous 2014 version of Artsakh’s Electoral Code had a weak gender quota, that could be met by having female candidates in the #6 and #11 spots on the party lists. To put that figure in perspective, since only two thirds of the seats were assigned by the party lists and there were seven parties running, only one party (the Free Motherland Party) received more than 4 seats off the proportional party lists in the 2015 parliamentary election. Fortunately, parties included more than the bare legal minimum number of female candidates, resulting in five women MPs among the 33 elected in 2015, four from the proportional lists and one in a local district in Stepanakert.

Although no change to this gender quota was foreseen in the first reading draft of the electoral reform bill, after public consultations, the gender quota was increased significantly to require at least every fourth name on the party lists to be a female candidate. The gender quota works both ways such that at least every fourth name on the party lists also has to be a male candidate.

One clause that received a lot of attention in Artsakh was the residency and citizenship requirement for candidates. To run for President, one must be at least 35 years old, have lived continuously in Artsakh for the past 10 years, and have not held any other citizenships other than the Republic of Artsakh for the past 10 years. Samvel Babayan, a military figure from the 1990s Artsakh War looking to run for President, was hoping to change that. He started a petition drive to remove the residency requirement as he lived in Russia from 2011-2016 and then in Armenia after that. He was also in prison from 2000 to 2004 for a failed assassination attempt on Arkadi Ghukasyan, Artsakh’s President at the time. He was arrested again in Armenia in 2017 on charges of illegal arms acquisition and money laundering but was released a year later after Nikol Pashinyan became Prime Minister. The new Electoral Code, in its final version, kept the 10 year residency requirement, which would make Babayan ineligible to run.

Even without the support of international agencies, Artsakh’s governmental bodies made their best effort at public consultation. On June 28, a day after the bill’s first reading, they consulted with election specialists from the Yerevan affiliate of Transparency International. On July 9, they met with representatives from ten political parties that hold no seats in Artsakh’s Parliament, and would not otherwise be able to be heard at the Parliamentary Standing Committee on State and Legal Affairs, which is debating the bill. On July 14, the committee held a joint session in Stepanakert with the members of Armenia’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on State and Legal Affairs. There was a desire to emulate many of the recent reforms in Armenia but implementing them in Artsakh presents additional technical, resource-based, and strategic complications. For example, the lack of Internet connectivity throughout much of the territory makes it infeasible to livestream by webcam most of the approximately 300 polling stations. The voter authentication devices that verify IDs in Armenian elections were too expensive for Artsakh to procure on its own (Armenia received them through a European Union grant). Also, publishing the voter lists after the election, as is the practice in Armenia, could provide too much information to the Azerbaijani military on the population sizes of villages near the Line of Contact. Arusyak Julhakyan, an MP from Armenia, suggested posting them physically outside the voting station instead of uploading them to the Internet. This compromise did make it into the final version of the bill. The joint session also discussed coordinating residency registration to clarify dual citizens of both Artsakh and Armenia as either Artsakh voters or Armenia voters.

Ashot Ghulyan, Speaker of Artsakh’s Parliament, in his closing remarks at the joint session acknowledged that Artsakh’s elections have not always been perfect but they have tried to make improvements based on their three decades of experience. He highlighted new accommodations for voters with disabilities – a significant group in war-torn Artsakh – to be able to vote at accessible polling locations. He invited international observers to send missions and provide reports with actionable recommendations for further improvement. He stressed that a strong Electoral Code is a standard-bearer, attesting to Artsakh’s commitment to democracy. Especially, in contrast to Azerbaijan’s trajectory, where the President succeeded his father, abolished term limits, and appointed his wife as Vice-President, electoral reform can certainly strengthen Artsakh’s argument that coming under Azerbaijani sovereignty is not an acceptable resolution to the conflict.

The most recent changes to Artsakh’s Electoral Code will not take effect until January 1, 2020 and thus will not impact the upcoming September 8 local municipal elections, which are regulated under the same national law. The changes were made relatively quickly to provide clarity in advance of the 2020 parliamentary and presidential election. With local municipal elections scheduled in 2020 for Gyumri and Vanadzor, Armenia’s second and third largest cities, there are hopes that Yerevan will also be able to make timely reforms, complete with a public consultation period, before the end of 2019. Stay tuned to EVN Report for the latest as those conversations also kick back into high gear.

related

Armenia’s New Electoral Code: Open vs. Closed Party Lists and Other Considerations

By Harout Manougian

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan promised to call snap elections as soon as the country’s Electoral Code could be amended to allow for a fair race. Currently there are two bodies forming recommendations. Harout Manougian looks at the intricacies of the Electoral Code and in this first article writes about open vs. closed party lists.

Armenia’s New Electoral Code: Thresholds, Alliances, and Coalition Government

By Harout Manougian

In this second part of our series on Electoral Code reforms in Armenia, Harout Manougian looks at the debate taking place regarding the minimum threshold of the total popular vote political parties need to secure to enter the country’s parliament.

Armenia’s New Electoral Code: Part III

By Harout Manougian

In this third part of our series on Electoral Code reforms in Armenia, Harout Manougian looks at the debate about quotas for women and ethnic minorities for the upcoming national elections.