Thu Jul 12 2018 · 7 min read

Armenia’s New Electoral Code: Open vs. Closed Party Lists and Other Considerations

Part I

By Harout Manougian

July 5 is Constitution Day in Armenia and government offices are normally closed. This year, however, one conference room in the National Assembly kept the lights on as Lena Nazaryan, member of the Yelk Alliance, presented her faction’s proposals for amending Armenia’s Electoral Code to the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform.

Two Bodies Forming Recommendations

Before diving into those proposals, first some background is required. Upon his election as Prime Minister on May 8, Nikol Pashinyan promised snap elections as soon as the Electoral Code could be amended to allow for a fair race.

To bring forward conclusions on what specific changes are necessary, he appointed the PM’s Special Commission on Electoral Reform on June 19 with the following 12 members:

- Chair of the Commission: Ararat Mirzoyan, First Deputy Prime Minister

- Secretary of the Commission: Daniel Ioannisyan, Founder and Program Coordinator of the Union of Informed Citizens NGO

- Artak Zeynalyan, Minister of Justice

- Suren Papikyan, Minister of Territorial Administration and Development

- Hovanes Kocharyan, Deputy Head of Police

- Tigran Mukuchyan, Chair of the Central Electoral Commission

- Nune Hovhannisyan, Member of the Central Electoral Commission

- Sona Ayvazyan, Executive Director of Transparency International Anticorruption Center

- Vardine Grigoryan, Democracy Monitoring and Reporting Coordinator at Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly Vanadzor

- Hamazasp Danielyan, Senior Fellow at Apella Institute for Policy Analysis and Dialogue

- Aghasi Yesayan, Center for Electoral Democracy NGO Chairman

- Vahagn Hovakimyan, Yelk Alliance Policy Expert and former journalist

The following day, June 20, on the initiative of Parliamentary Speaker Ara Babloyan, the four factions (parties or alliance of parties) represented in the National Assembly jointly announced the formation of a Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform. It would also consist of twelve members, three from each of the four factions, as follows:

Republican Party of Armenia (RPA)

-

Arpine Hovhannisyan, MP, Deputy Speaker of NA

-

Davit Harutyunyan, Former Minister of Justice

-

Vigen Sargsyan, Former Minister of Defense

Yelk Alliance (YLK)

-

Edmon Marukyan, MP

-

Lena Nazaryan, MP

-

Grigori Dokhoyan, Bright Armenia Party member

Tsarukyan Alliance (PAP)

-

Naira Zohrabyan, MP

-

Sergey Bagratyan, MP

-

Gevorg Petrosyan, MP

Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF)

-

Armen Rustamyan, MP, Faction Leader

-

Spartak Seyranyan, MP

-

Lusine Hovhannisyan, ARF Party Member

Note that the Electoral Code is distinct from the Constitution, which was most recently amended in the December 2015 referendum. Whereas amendments to most articles of the Constitution require a national referendum, amendments to the Electoral Code only require a three-fifths (60%) majority of all members of the National Assembly – whether they are present to vote or not. For that reason, the Parliamentary Working Group has agreed to proceed on the basis of consensus between the four factions. In actuality, if the Republican Party MPs can maintain a united front, they would hold an effective veto over any changes as they represent more than 40 percent of the seats in parliament.

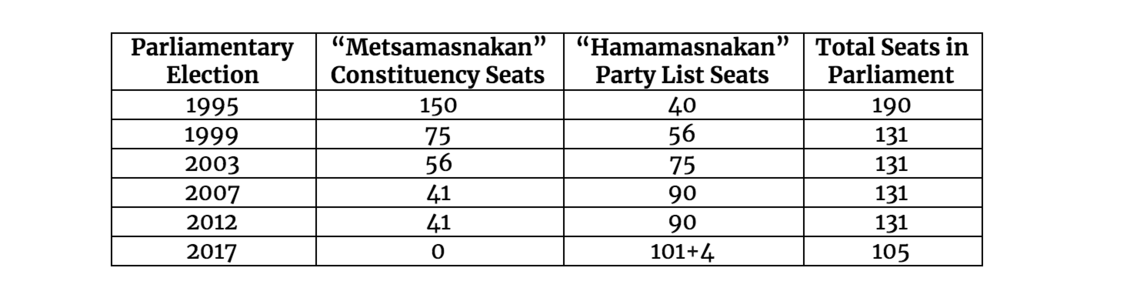

The Electoral System: Party Lists

Since 1995, Armenia had used a system called mixed member majoritarian. That is, members of parliament were elected in one of two ways. The first group ran as candidates in geographic constituencies, which elected one member each. The approach has a misleading name in Armenian: “metsamasnakan.” However, whereas that term directly translates to “majority,” in practice only a plurality was required. The winner would be the candidate who received the most votes in a given district, which did not necessarily need to be more than 50 percent if there were more than two candidates.

The second group was selected in parallel from nationwide party lists. In addition to casting a vote for their local candidate, each voter also cast a vote for a political party on a different piece of paper and dropped it into a different ballot box. This “hamamasnakan” (“proportional”) group was allocated seats depending on the percentage of votes collected. Each party’s list was ordered such that if they earned twelve seats, the first twelve names on their list would be elected to parliament. Though this second batch of MPs was allocated to parties in proportion to their share of the popular vote, the National Assembly as a whole, with both groups together, did not reflect the national vote share due to the constituency seats.

Over the years, the balance shifted from mostly constituency seats to mostly party list seats until the 2015 constitutional referendum required a fully proportional model, abolishing constituency seats completely.

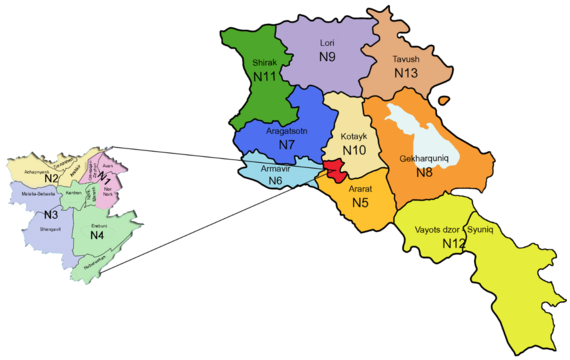

In abolishing constituency seats, the 2015 Constitution approached territorial representation in a different way. Instead of single-member plurality-elected districts, each party would now present 13 territorial party lists in addition to their usual national party list. The new electoral districts corresponded with the borders of each marz, except for Vayots Dzor and Syunik, which were merged into one (Vayots Dzor being the least populous marz). The Yerevan Capital Region was divided into four separate districts.

Voters in, say, Lori marz in choosing to vote for a given party, could also identify their favorite candidate from that party’s Lori territorial list, though this was optional. They could no longer, however, vote for a local Lori candidate from one party and the national list of another party. The two had been merged into one piece of paper cast into one ballot box.

Under the new rules, half of a party’s allocated MPs were selected off the top of the national party list. The other half were taken from the territorial lists as follows:

1- Find the electoral district in which that party received the most votes

2- Within that district, the candidate for that party who received the most individual votes (compared to the other candidates of the same party in the same district) is elected

3- Divide the party’s vote total in that electoral district by 1 plus the number of candidates already elected and repeat from step 1 until the party has filled all its allocated seats.

Graphic Source: Central Electoral Commission

It is important to note that this approach does not claim to provide a result that will divide representatives evenly across the districts. Neither does it claim to guarantee that the candidates with the most individual votes will be elected. It does, however, offer some choice to the voter to impact which individual candidate may get to represent them. This system also has a misleading term in Armenian. It is referred to as the “ratingayin” component. However, it does not provide an opportunity for the voter to rank every candidate from their chosen party in order of their preference. They can select only one person.

The New Proposals

The ratingayin territorial component is unpopular with all parties except the Republican Party of Armenia. Since all votes cast for a local district candidate also count for that candidate’s party’s national list, an incumbent established party can use it to its advantage by recruiting several local candidates to compete against each other, driving up the total turnout for their party, allowing those on its national list to reap the rewards.

To replace it, the ARF has proposed what seems to be an unworkable solution: unlimited open-list ranking at a national level. Each voter would get to indicate their order of preference among all candidates from all parties. Parties tend to submit national lists of 150 candidates. The 2017 election saw nine parties or alliances register. Thus, the ARF proposal would be to allow each voter to indicate in order from 1 to as much as 1350 which candidates they prefer. Although the system (known as Single Transferable Vote) is used in countries with territorial districts to elect as many as seven representatives from an area, using it at a national scale to elect 101 representatives puts an exponentially higher burden on both the voter, who would need to differentiate between hundreds of candidates, and the poll officials who need to tally the results.

In electoral system parlance, arrangements that allow voters to choose from among a party’s candidates are called “open-list” systems, while those where the order is fixed are called “closed-list” systems. Daniel Ioannisyan, Secretary of the PM’s Special Commission, explained to the Parliamentary Working Group that they have settled on recommending a closed-list system but that he resents the negative connotation of that term. He prefers calling it the “traditional proportional” system to make it clear that the lists are publicly available and that it is the party list approach Armenia has been using since 1995. Perhaps “fixed-list” would be more descriptive.

One of the preliminary conclusions of the PM’s Special Commission already brought to the Parliamentary Working Group by the Yelk Alliance is to use a closed-list system. Further details such as requirements for gender representation (currently 25 percent) or territorial representation have not yet been concluded.

Sergey Bagratyan, from Tsarukyan’s Prosperous Armenia Party, in presenting his recommendations to the Parliamentary Working Group, agreed with one national closed-list approach. He said that it strengthens the role of parties, centring campaigns on ideas and policies instead of individuals and their personal connections. It also gives every MP a national outlook instead of overly focusing on the interests of one specific district. He suggested incorporating candidates from outside of Yerevan by requiring every sixth name on a party’s list to have been resident in a marz for the last five years. The marzes would be ordered by population, according to the most recent national census. The implication is that a party would not be required to have a candidate from the Vayots Dzor marz until the 60th name on their list – no party currently has 60 members in the 105 member National Assembly The ratio is skewed as two thirds (67 percent) of registered voters are from outside Yerevan.

RPA members commented that the residency requirement was problematic. Most MPs move to Yerevan to serve in the National Assembly upon their election. It was not immediately clear what verification procedure would certify a candidate’s eligibility for a marz spot on the list under the PAP proposal.

Beyond the party list system, there are many other aspects being examined as part of the Electoral Code amendment process. EVN Report will provide you with the latest analysis in future features.