Wed Aug 08 2018 · 8 min read

Armenia’s New Electoral Code: Part III

Quotas For Women and Ethnic Minorities

By Harout Manougian

Rwanda and Armenia do have something in common but it is not their percentage of women in parliament. At 61 percent, Rwanda’s proportion of female representation in its legislative lower house is the highest in the world. Armenia is 110th, but still ahead of its neighbors, Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Artsakh, and Iran.

On the set of the ArmComedy talk show, Member of Parliament Naira Zohrabyan, an outspoken member of the Prosperous Armenia Party (PAP), lamented Rwanda’s path to greater female representation as an “American experiment.” She does want to see more women colleagues but wants it to be clear that each one earned their position from their own abilities.

In 2003, Rwandan President Paul Kagame oversaw a constitutional referendum that imposed a minimum 30 percent quota for women in parliament. It achieved that target by reserving 24 of the 80 seats in the Chamber of Deputies (legislative lower house) for women candidates. Only women could run for these seats and only women could vote for them. The remaining seats could be contested by both women and men.

Armenia currently has a gender quota but it works very differently. Each set of four candidates on a party’s (or alliance’s) national proportional (hamamasnakan) list needs to include at least one male and one female. Thus, it is not a quota for women per se, but applies both ways. In 2017, these lists were used to assign half of the representatives in the National Assembly. The other half were chosen directly by voters using the ratingayin system, where fewer women tended to get elected. (See Part 1 for a refresher on the hamamasnakan, metsamasnakan, and ratingayin components.)

Under the current electoral code, before any amendments, that 1 in 4 (approximately 25 percent) ratio is already scheduled to be tightened to 1 in 3 (approximately 33 percent) after January 1, 2021. That is, every set of three candidates on a party’s list would include at least one male and one female. With snap elections slated for either late 2018 or spring 2019, the Prime Minister’s Special Commission on Electoral Reform has proposed to accelerate that schedule so that the 1 in 3 ratio would apply for the upcoming election. It has also proposed scrapping the ratingayin component, which did not include any gender quota. The expected result would be for the next group of Armenian parliamentarians to be at least 33 percent female, on par with the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Austria.

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) agrees with instituting this higher quota for the next election however one of their MPs, Spartak Seyranyan, raised eyebrows during the debate at the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform when he declared, “I am deeply convinced that the current 1 in 4 quota is several times greater than the actual current political potential of women in Armenia.”

It is worth noting that the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform itself includes four women, one from each parliamentary faction, among its 12 members. The PM’s Special Commission on Electoral Reform includes three women among its 12 members.

It was Yelk MP Lena Nazaryan who raised the bar another rung. She proposed a 40 percent gender quota (ahead of Denmark, Iceland, and New Zealand) for the upcoming election. That threshold came from feedback by women’s rights NGOs during their consultation with the PM’s Special Commission. Naira Zohrabyan brokered a compromise, accepting the 40 percent quota but making it effective only after January 1, 2024, which was agreed to by all parties. From that date, each set of five names on a party’s national list will have to include at least two males and two females.

Lastly, Spartak Seyranyan clarified that gender quotas were not incompatible with the open list proposal put forward by the ARF, where voters could choose individual candidates directly, instead of the order decided upon by each party. In the event that not enough women were elected from a party, the female candidates who received the most votes would bump out their male counterparts (who actually got more direct votes than them) until the quota was met. The Yelk and Tsarukyan factions, both of whom prefer closed lists, did not bother debating the problematic interpersonal dynamics that such an approach would create.

Ethnic Minority Quotas

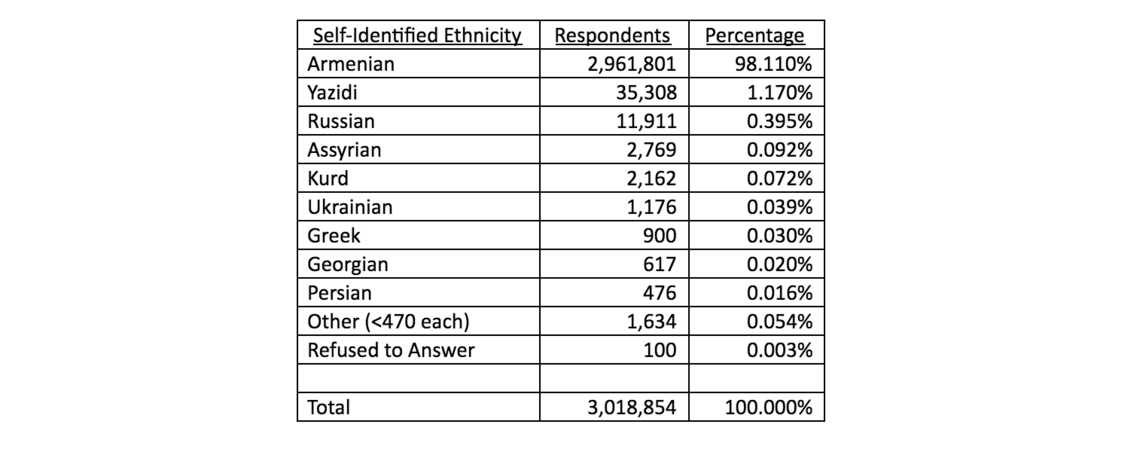

Armenia is a very ethnically homogeneous country. In the most recent 2011 national census, 98 percent of respondents self-identified their ethnicity as Armenian. Other responses included the following:

The new 2015 Armenian Constitution introduced a guarantee for ethnic minority representation in parliament, the specifics of which it left up to the electoral code.

The system that was used during the 2017 parliamentary elections arguably gave very little say to those ethnic minorities as to who their representatives should actually be. However, among the Parliamentary Working Group’s 35 recommendations, submitted to the PM’s Special Commission, none of them proposed changes to this aspect of the electoral code.

Currently, the electoral code allows for the four largest minorities, as determined by the most recent national census, to be given one seat each. Each party or alliance submits a list with two parts. Part 1 of the list is the regular national proportional list (the one that has a gender quota as discussed above). Part 2 of the list is specifically for ethnic minority representation. Each party or alliance can designate a Yazidi, Russian, Assyrian, and Kurdish candidate in Part 2 of their list. They can even designate up to three backup candidates under each ethnic minority but they would only take a seat in parliament if the candidate assigned the first position vacated their seat (due to resignation or death, for example).

The way the ethnic minority seats are assigned, however, effectively provides additional bonus seats to the largest parties. The algorithm specified in the current electoral code is the following:

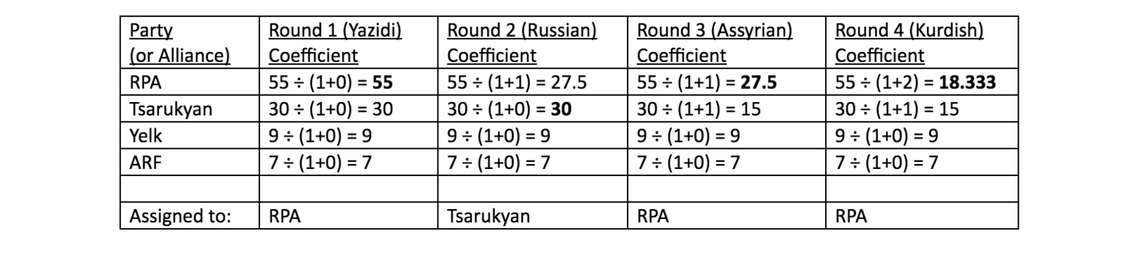

1- Calculate a coefficient for each party by dividing their portion of the initial 101 seats by 1 plus the number of ethnic minority seats already given to that party.

2- Assign the seat for the next largest minority to the party with the largest coefficient.

3- Recalculate the coefficients and repeat from Step 1 until all 4 ethnic minority seats are assigned.

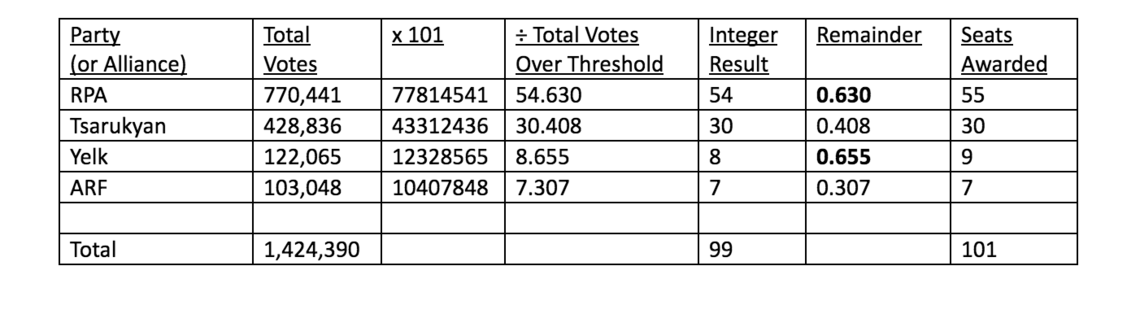

To better visualize how this system played out during the 2017 parliamentary election, the following table shows how the initial 101 seats were awarded. After disregarding votes that went to parties who did not meet the minimum threshold (See Part 2 of this series for an explanation of party thresholds), the vote counts of each remaining party are multiplied by 101 (the number of proportional seats) and divided by the total votes of the remaining parties. The result is rounded down to the largest whole number. Rounding down will result in a total less than 101, and so the parties with the largest remainder (in 2017, this was Yelk and RPA) are assigned the remaining seats until the total number is 101.

Now that the initial 101 seats have been awarded, the ethnic minority representatives can be assigned. The largest minority is the Yazidi community, and so the Yazidi candidate for the largest party (RPA) is elected. The RPA coefficient is then recalculated, dividing it by two. Now, the Tsarukyan Alliance has the largest coefficient, and so their candidate for the second largest minority, the Russians, is elected. The process continues for two more rounds, resulting in the RPA’s Assyrian and Kurdish candidates also getting elected. The four additional seats are added to the original 101, bringing the total in the National Assembly to 105.

It is worth noting that neither Yelk nor the ARF actually presented any ethnic minority candidates on Part 2 of their party lists in the last election. Thus, even if they had a coefficient large enough to earn one of these four seats, it would have passed on to the next party anyway. Of the nine parties that contested the 2017 election, only the RPA, Tsarukyan Alliance, Armenian National Congress (ANC), and Armenian Renaissance included ethnic minority candidates.

On July 2, 2018, the PM’s Special Commission on Electoral Reform met with representatives of ethnic minorities to hear their comments on potential changes to the electoral code. Secretary Daniel Ioannisyan presented two potential approaches:

The first approach was recommended by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) Venice Commission, suggesting that each party be required to include a minimum quota of ethnic minority candidates on their single national candidate list, eliminating the separate Part 2 list for ethnic minorities.

The second approach maintained the separate Part 2 list for ethnic minorities but assigned the winner according to which party collected the most votes in polling locations with the largest concentration of that ethnic minority.

Knyaz Hasanov, the current RPA MP representing the Kurdish community, said that the second approach was a non-starter for him because the Kurdish community is too widespread across the country for any set of poll locations to accurately reflect their political preferences.

Meline Gasparyan, President of the Assyrian Federation, was upset that neither of the two proposals, nor the current process, allowed ethnic minorities to choose their own representatives. She proposed a different model where ethnic minorities participate in the national election but also get a second vote for the representative of their ethnic minority they believe would best represent them (instead of the person that a political party has hand-picked). She went on to assert that if ethnic Armenians are going to pick who the ethnic minority representatives are going to be, the provision may as well be eliminated.

Another proposal was put forward to allow the creation of ethnic minority-focused parties, which would have a lower threshold of 1 percent to enter parliament. Given Armenia’s demographics, however, even at that lower threshold, it is unlikely for such parties to secure enough votes to enter parliament.

The issue of how best to represent ethnic minorities, a requirement introduced in the 2015 constitution, is far from simple. No final recommendation has been made by the PM’s Special Commission. It may adopt the Venice Commission’s approach of an ethnic minority quota incorporated into each party’s national list. Even that approach can get very complicated as it raises questions such as:

Should the quota be for all ethnic minorities as a group or for each one separately?

If separately, should the arbitrary number of the top 4 groups continue to be used or should the cutoff be a demographic figure, such as 1% of the population?

Since parties will rarely have more than 40 members of parliament, should the quota be to only have a minimum of one ethnic minority candidate among its first 25 names.

What if a party can’t recruit an ethnic minority candidate?

Who counts as an ethnic minority? Is self-declaration adequate? Should language skills be necessary?

Whatever the answers to these questions, one way or another, it is likely that ethnic minority representatives will be incorporated into the base group of 101 parliamentarians, instead of a bonus allocation to the largest parties.