Mon Jul 05 2021 · 7 min read

A People’s Constitution Must Be Framed by the People

By Harout Manougian

July 5 marks Constitution Day in Armenia, a national holiday that celebrates the passage of the country’s first Constitution in a referendum on July 5, 1995. Unfortunately, that July 5 date falls short of living up to an event to be proud of.

Soon after Armenia’s referendum on independence passed on September 21, 1991, a presidential election followed on October 17, confirming Levon Ter-Petrosyan, who had been Speaker of the legislature since 1990, as the head of state. The legislature, then-called the Supreme Council, which consisted of MPs elected prior to independence, was split on two models for the constitution. Ter-Petrosyan’s faction favored a strong presidency, while the opposition advocated for a parliamentary republic. Ultimately, the President got his way in a referendum that OSCE Parliamentary Assembly observers deemed “free but not fair.”

The Armenian word for constitution, sahmanadrutyun, communicates the concept of setting limits. When a government gets to set the limits that they themselves will be subjected to, the natural tendency is to minimize safeguards and maintain broad leverage; everyone trusts themselves to handle more power. But the purpose of a constitution is the opposite: to imagine the day when you are not in power and install the guardrails that you would not want your opponent to cross.

Armenia’s first three presidents all transformed the Constitution in their own image. Ter-Petrosyan wanted wide-reaching presidential powers, and he passed them in 1995. Robert Kocharyan wanted immunity from prosecution for actions taken while serving as President, and he passed them in 2005. Serzh Sargsyan wanted to lift term limits on the head of government, and he passed them in 2015. Nikol Pashinyan has also made his intentions to reform the Constitution known, establishing an Expert Commission on Constitutional Reform in early 2020. A year ago on this day, Pashinyan’s Constitution Day message read:

Today, we are marking Constitution Day in Armenia, and I congratulate all of us on this occasion. However, it is necessary to honestly state that, although we all understand the importance of the Constitution in terms of building state institutions, streamlining public and state relations, this holiday implies some half-heartedness and raises specific misgivings.

Three times in the history of the Third Republic of Armenia, our people adopted a new Constitution or constitutional amendments by referendum. However, the results of none of those referendums were considered trustworthy by society. The citizens of Armenia did not consider the decisions on adopting or amending the Constitution, nor did they consider the Constitutions so adopted as their own.

This is the biggest systemic flaw in our state structure, because the Constitution should be an agreement of citizens on citizen-to-citizen and state-citizen relations. Consequently, the state system should be supported by the collective will of all citizens, which should become a factor guaranteeing the inviolability of statehood, evidence of citizens’ responsibility for the fate of the state, and an expression of citizens’ will to have a state.

The analysis of a number of events, especially in the recent period, has led me to the conclusion that the citizens of Armenia often do not consider the country’s state system as their property, do not see an organic connection of this system with their will. Although my position was that frequent changes to the Constitution subject the state system to inappropriate stress, constant changes to the Constitution lead to uncertainty, the realization of these circumstances led me to the conclusion that our country needs a new Constitution, which should lead to a political system based on the free will of our citizens.

Accordingly, the new Constitution should not be conceived to suit the tastes and mores of a particular individual, political force or group, nor to ensure the reproduction of any power, but to address the strategic issue of formulating the citizens’ free will to have a statehood of their own.

This process has already started, and we hope that the draft Constitution will be put up for the widest possible public debate, and the new Constitution will be adopted through a nationwide referendum in 2021. I wish all of us every success in this important matter.

The work of the Commission was first interrupted by the coronavirus pandemic and then the 2020 Artsakh War and the political crisis that followed it. It included members from the opposition Prosperous Armenia and Bright Armenia parties, who took a position after the war that continuing the work and holding a constitutional referendum in a period of political instability was not feasible. Now, after the June 20 early parliamentary election, both those parties have lost all their seats in Parliament, replaced by the Armenia Alliance and I’m Honored Alliance.

It is not clear at this point in what form the work of the Commission will continue going forward. Some starting principles had initially been agreed to: maintaining the parliamentary system of governance and eliminating the “stable majority” provision that triggers a runoff election between the top two political parties if a governing coalition cannot be formed.

That consensus was apparently thrown to the wind by Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan at his rally on March 1, 2021, following a call by senior military leaders for him to step down, where he declared that, “I think it is time to state that we must work to pass a new Constitution or Constitutional amendments through a referendum in October this year [2021]. Finally, the transition to a semi-presidential system of government must be one of the possible options.”

While a referendum in October is not likely, constitutional reform is certainly still on the mind of the re-elected Prime Minister. The morning after the June 20 election, he stressed in a tweet that “the Civil Contract Party will have a constitutional majority.” While he intended to imply that his party would have at least two-thirds of the seats in the new parliament, his projection was not accurate. The Armenian Electoral Code includes a provision that opposition parties must occupy “at least one third” of the seats, leaving Civil Contract with 71 out of 107 seats, one vote shy of a two-thirds majority. In this year’s message, Pashinyan promised to “measure seven times before making a cut,” suggesting that constitutional reform will not be rushed early in his renewed term.

Most articles of the Constitution can be changed by Parliament, without a referendum, with a two-thirds vote by Parliament. In seeking to eliminate a grandfather clause exempting some Constitutional Court judges from their 12-year term limit, the My Step Caucus could have taken this road in early 2020. However, they found it more politically expedient to put the question to a referendum instead. In order to call a constitutional referendum, a measure must pass a lower three-fifths majority in Parliament first. In the end, the referendum was cancelled due to the pandemic, and a milder version of the amendment (which imposed the 12-year limit on all sitting judges, instead of dismissing even those who had served less than 12 years) was passed by a two-thirds majority in Parliament, without a referendum.

Of the People, By the People, For the People

“The new Constitution should not be conceived to suit the tastes and mores of a particular individual, political force or group…” These are the Prime Minister’s own words. An example of how to live up to them can be found in Ireland, where a “Constitutional Convention” was set up in 2012. In contrast to the 1787 U.S. Constitutional Convention, which was an assembly of local statesmen from the original thirteen states (Rhode Island was invited but did not send any delegates), Ireland built on a Canadian concept of “Citizens’ Assemblies” to broaden its representativeness in formulating reforms. A third of the 100 members of the recent Irish Constitutional Convention were elected politicians, while the other two thirds were chosen from among the general public, in a random selection that maintained age, regional and gender representativeness. Now, of course, the average Irish citizen is not a constitutional expert; they did not need to be. Their function was more akin to a jury, rather than the authors of the changes. Actual constitutional experts would present various topics to them, ranging from electoral systems to their constitutional restriction on blasphemy. The participants would spend 10 weekends hearing differing views, ultimately proposing which changes to bring to a referendum in what order. The Convention did not have the power to make final changes themselves; they were the sounding board for what could be brought to the people in a referendum. Instead of one take-it-or-leave-it package deal, the resulting referendums were specific to one concept at a time, allowing for more nuanced deliberation during the voting process, rather than rejecting an entire package due to one provision, or accepting a package that included elements one did not agree with.

So far, in Armenia, Pashinyan’s approach to forming a constitutional package has greatly resembled that of Serzh Sargsyan before him. But there are more participatory models that we can look to.

Broadening the Agenda

If Armenia took the example of Ireland, combining politicians with non-partisan citizens, additional questions they could and should consider include:

-

Imposing a ten-year term limit on the post of Prime Minister

-

Revisiting the ban on dual citizens running for office or being appointed to government posts

-

Shortening regular electoral terms from five to four years

-

Setting fixed election dates for regular elections and synchronizing municipal elections within a region

-

Revisiting the reserve powers available to the President, including adjourning Parliament to call an early election

-

Revisiting the selection process and roles of regional governors

-

Allowing 16- and 17-year-olds to elect non-voting representatives to their local city council

-

Revisiting the suspension of rights under a State of Emergency or Martial Law

-

Staggering appointments to the Central Electoral Commission

-

Restricting changes to the compensation of MPs from taking effect until after the next election

None of these topics are currently on the agenda in Armenia. The existing Commission’s sessions are all closed, with no opportunity to make deputations. Adopting a more public format, where citizens can bring real participation, could one day resolve the “half-heartedness” and “specific misgivings” that still overshadow Armenia’s Constitution Day.

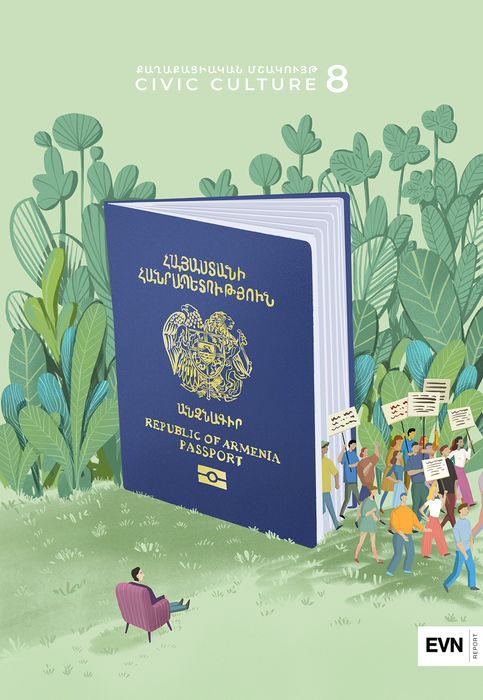

Magazine Issue N8

Civic Culture

Understanding the rights and responsibilities of good citizenship is an ongoing process and involves many aspects from obeying the law to taking responsibility for oneself and to voting in elections. The June issue features stories about those rights and responsibilities, including individual awareness, the role of civil society and the role of the judiciary in defending human rights.

The Judiciary as Government Regulator

By Zara Hovhannisyan

The effectiveness of the justice system determines the level of respect for human rights in a country. It remains to be seen what steps the new government will take and whether the provisions of the strategic judicial reform program will be implemented.

Citizens With Abundant Rights, Constrained by Stereotypes

By Astghik Karapetyan

In order for a democratic society to function, citizens must exercise their rights and responsibilities. The state is obligated to take steps to shape an independent and strong civil society, Astghik Karapetyan writes.

The Mirror in the Lavatory

By Karen Avetisyan

How people behave in public spaces compared to private ones and how they perceive their individual civic responsibility is a reflection of the society in which they live.

Also read

Why Is Armenia Terrible at Foreign Policy? The Failure of Multi-Vectorism and the Need for a New Doctrine

By Nerses Kopalyan

Armenia’s defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War was a collective failure of all state bodies and institutions. The new Armenian government must construct a foreign policy doctrine defined by “strategic engagement.”

It Has to Be Said: Points of Convergence

By Maria Titizian

After a bitter election campaign, three political forces are poised to enter parliament. What they do and how they behave will determine the future of the country.

This week's podcast