Mon Dec 09 2019 · 7 min read

Aligning Communication, Policy and Finance: Where Are We on the Road to a Knowledge Economy?

By Samson Avetian

The annual budget discussions in Armenia are not known for arousing public interest. This year was not very different, even with personal income tax cuts and other policy adjustments on the horizon. Mostly, budget proposals and announcements have been quite encouraging, especially given the fact that the shadow economy subsided in 2019, generating substantially higher national budget revenues.

Allocations to the educational, science and research domains are particularly important. Ultimately, labor force quality is one of the main drivers of productivity growth. For Armenia to flourish economically, this variable is critical.

So how has Armenia performed in recent years in this area? Where does it stand in international comparisons? How much financing should be allocated to different branches and activities? Let’s dive into the numbers.[1]

Armenia’s Comparative Performance and Recent Trends

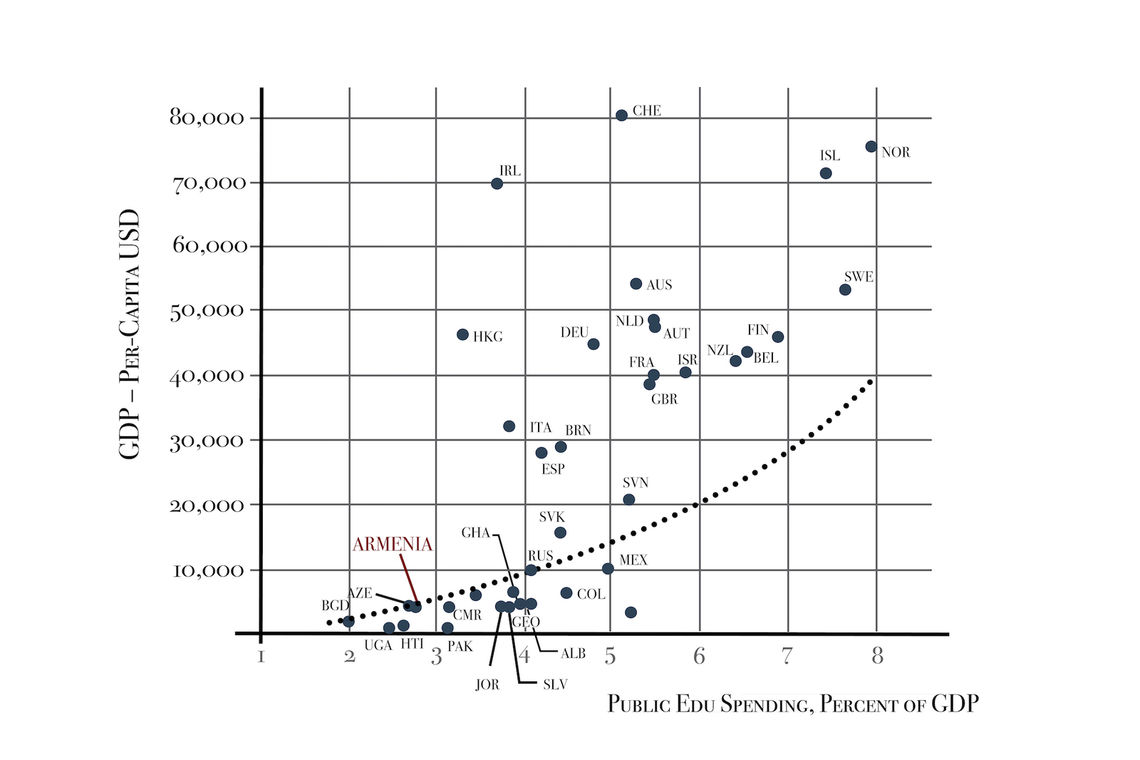

Public spending on education tends to correlate strongly with productivity and, consequently, standard of living. Many research studies have explored this relationship. The chart (Figure 1.1), prepared by the World Bank, suggests that greater public spending on education is associated with higher per-capita GDP. Although correlation does not necessarily imply causation, both theory and empirical data point in the same direction.

Education Spending and GDP Per-Capita

2016-2018 averages

Figure 1.1/Source: World Bank,WDI Databank

Looking at the chart, it becomes evident how poorly Armenia performs in comparison to other countries, allocating some 2.5% of GDP to education. Certainly, this is not in line with the public discourse or long-term policy vision of the knowledge-intensive economy that Armenia needs to achieve.

To be fair, since the beginning of this decade there seems to have been some allocations to education-related initiatives (foreign undergraduate and graduate level scholarships) that were financed outside of the state budget, similar to the work of the Luys Foundation. However, even including these figures would not lead to perceptibly higher numbers in Armenia’s case.

One can also debate how well financial inputs correlate with the quality of the educational output. I will abstain from this circular argument due to Armenia’s (regrettable) absence from international benchmark studies, such as the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). There is unfortunately little, if any, evidence to suggest that Armenian public education is more efficient or effective than other countries.

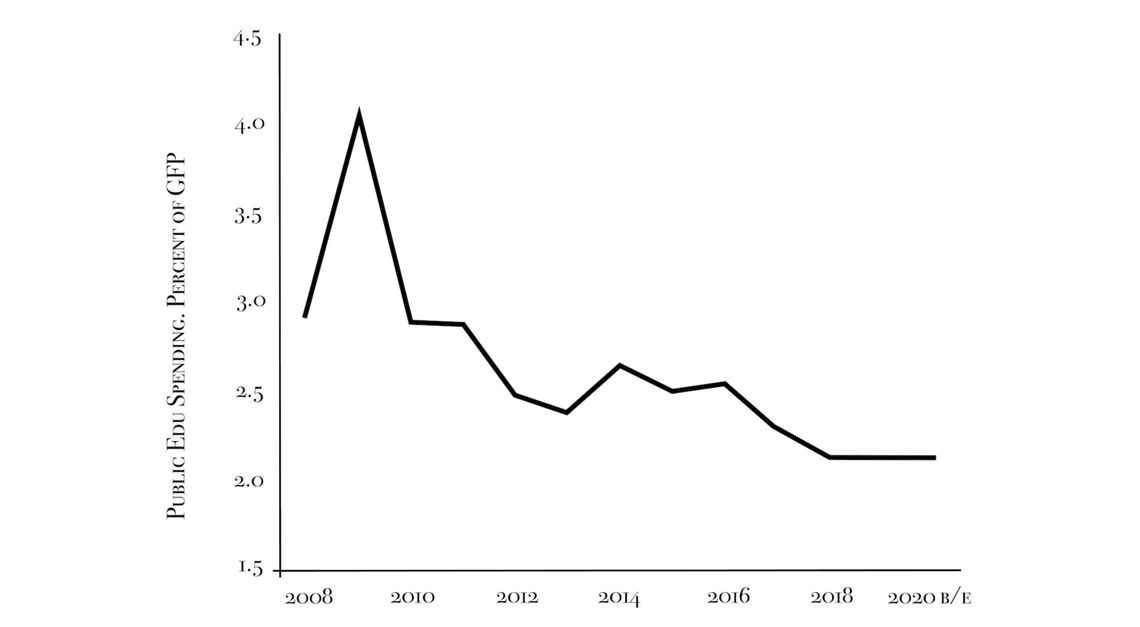

If the first chart presented a static picture of the current state of events, this second one (Figure 1.2) illustrates the trend in recent years. Again, there has been a perceptible dissonance between this trajectory and the communicated policy orientation.

Education Spending

Figure 1.2/Source: gov.am; minfin.am

It seems that neither the 2019 nor the proposed 2020 budget—which recently passed in parliament—moves the needle. More on this below.

International Best Practice With Regard To Public Sector Education Spending

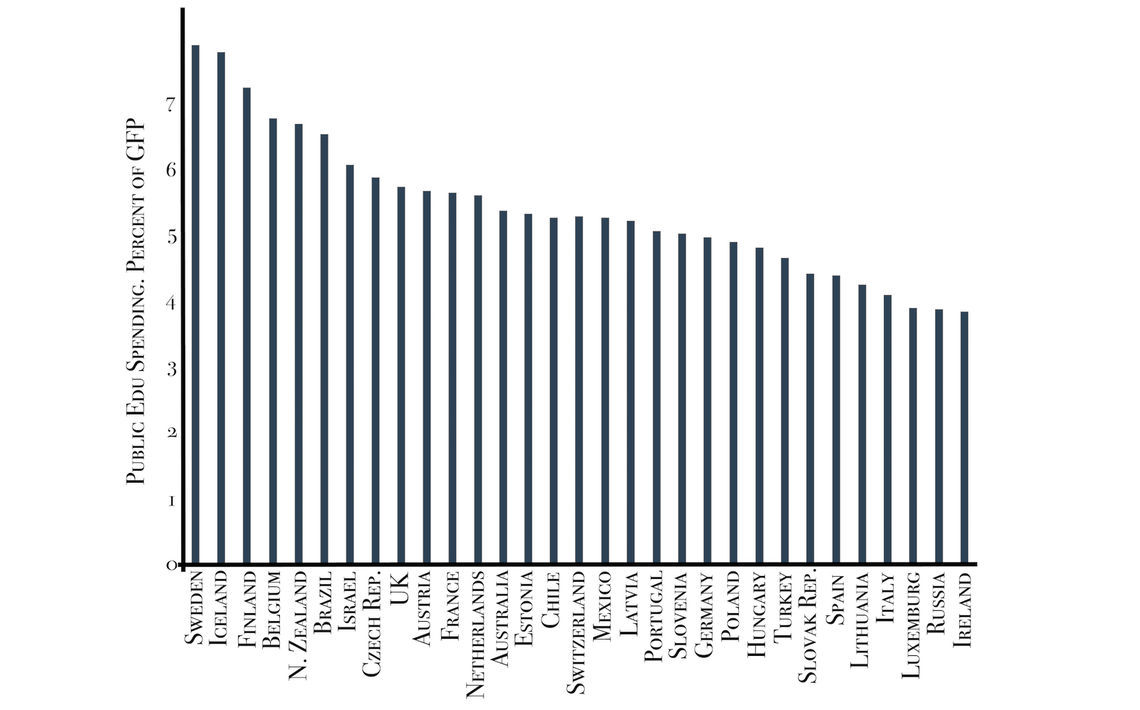

So what are some of the targets that Armenia needs to put in place in order to achieve the vision of a “knowledge-based economy”? Two metrics are of interest: public sector spending on education as well as on research and development (R&D). Both, as customary and for comparative reasons, are measured as a share of GDP.

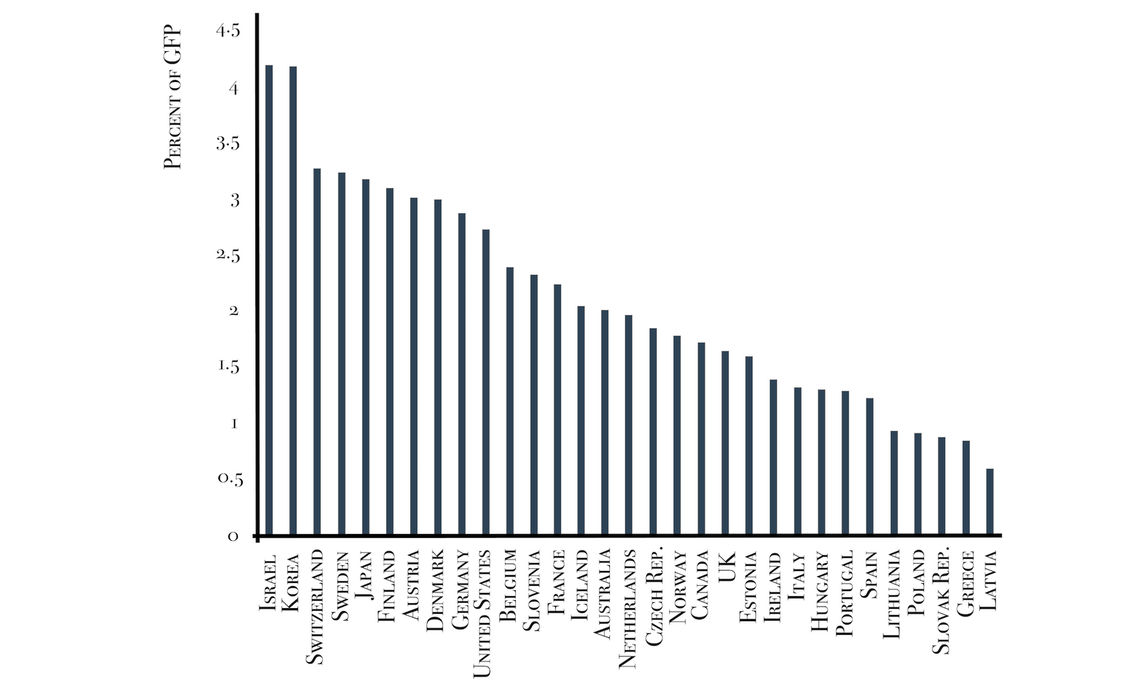

On the first metric, Public Education Spending as a share of GDP, the accompanying chart (Figure 1.3) shows the rank of OECD nations. Armenia needs to more than double its current educational spending as a share of GDP (~2.5%) in order to catch up to countries like the Czech Republic, Estonia and Latvia, which represent the middle of the pack.

Education Spending in OECD Nations

2015-2016 averages

Figure 1.3/Source: OECD

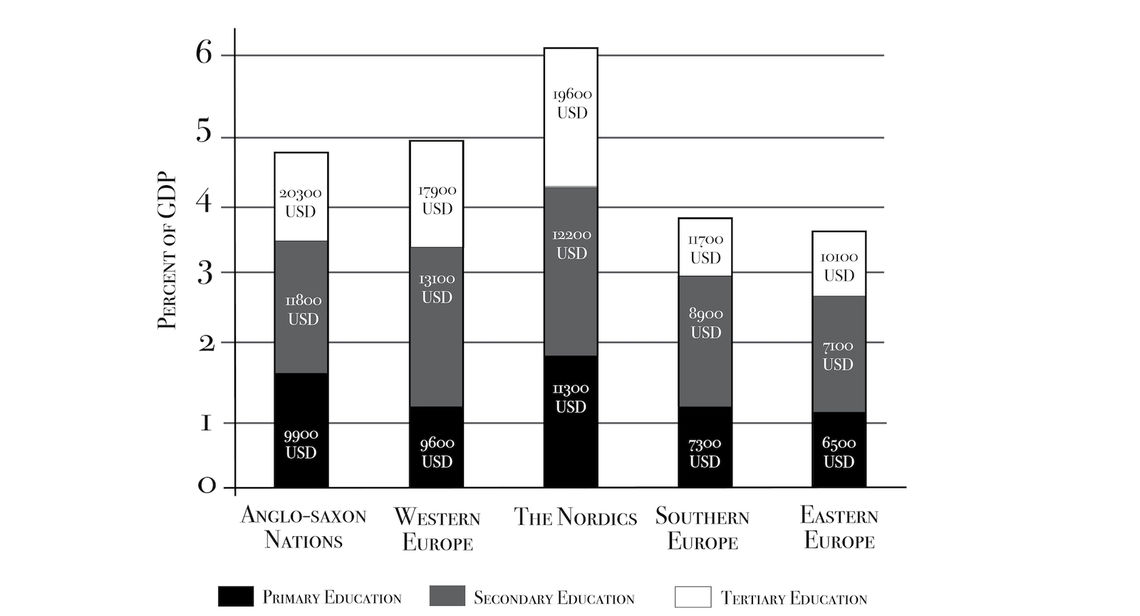

The next chart (Figure 1.4) illustrates how the money is divided among the different stages of education. As depicted, Secondary Education gets most of the financing in all country groupings[2] (~2% of GDP). The biggest difference across these groups is how much is spent on Tertiary Education. The clear outperformers here are the Nordic countries like Sweden, Denmark and Finland (~2%). These nations spend almost twice the amount some of their peers do (ex. Southern & Eastern Europe at ~1%).

The chart also indicates how much is spent per student in USD. Here, as an example, at the tertiary level, the Anglo-Saxon nations come across as the most costly at 20,300 USD per student on average. The Nordic countries seem to be spending somewhat less per student (19,600 USD) but educating a relatively higher number of undergraduate and graduate students.

Education Spending Per Stage, 2016

Figure 1.4/Source: OECD

When it comes to Research & Development, segregated data for Armenia is not available. International benchmarks, on the other hand, are provided in the next two charts. The first figure illustrates how much is spent per country. As illustrated, the numbers range between ~0.5% and ~4% of GDP, with substantial deviation between peers.

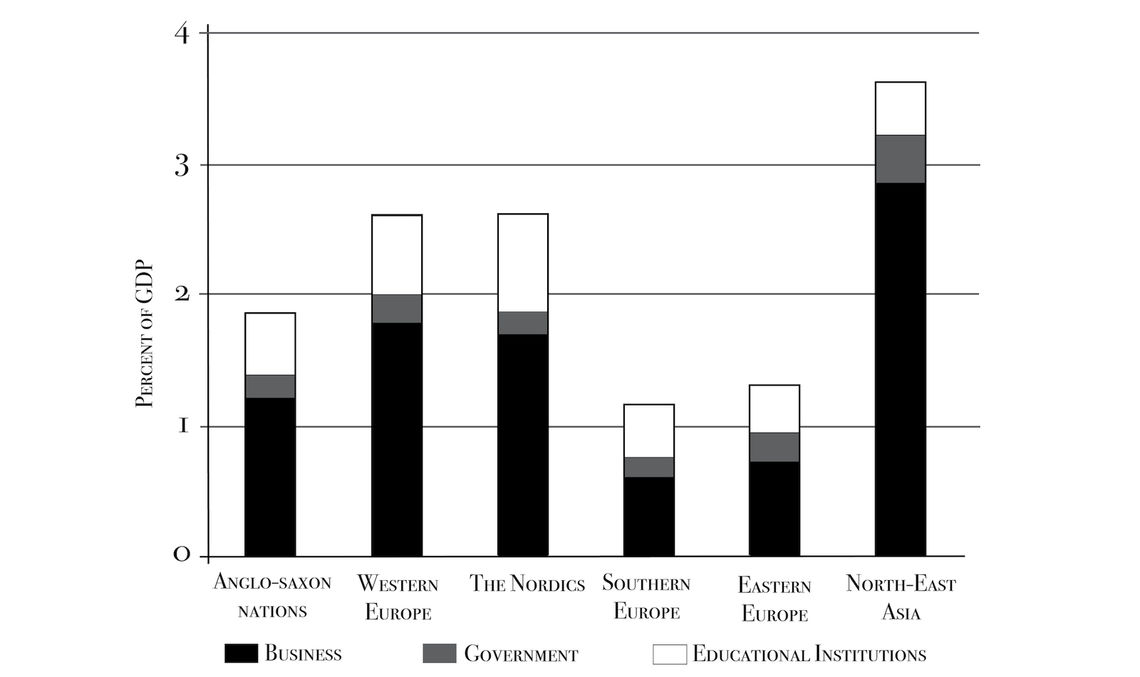

The next chart (Figure 1.5) takes a similar approach and divides R&D spending in the economy by country grouping and financing sector. The Business sector (Figure 1.6) contributes the largest chunk in all groups, while direct Government funding is a much smaller amount.

Secondly, the variations between nations are much larger here, with countries like Japan and South Korea significantly ahead of the rest.

Another takeaway is that OECD governments seem to be spending on average around 0.2% of GDP on R&D, significantly less than the 4-5% they spend on education.

To summarize, high performers allocate some 10% of their GDP into Education as well as R&D activities. Not coincidentally then, one finds the top-ranked countries on these two metrics also headlining international competitiveness rankings prepared by the World Economic Forum, IMD Business School and others.

Armenia’s 2.5% figure (granted this excludes R&D financing) has a significant gap to close.

Total R&D Spending

2012-2016 averages

Figure 1.5/Source: OECD

R&D Spending Per Sector

Average 2014-2016

Figure 1.6/Source: OECD

Financing Needs to Increase – Accompanied by Reforms and Shifts in Approach

It is clear that Armenia significantly lags its peers in public spending on education. The question is whether the current system is apt and ready enough to accommodate increases in available financing or does it first need to be reformed and modernized, in line with labor market requirements, before such allocations are increased. One is inclined to interpret the recently announced and substantially higher budgetary allocations to the Ministry of High Tech Industry in such a way. The financing to this newly-created Ministry quadrupled, reflecting its strategic alignment, effectiveness and purpose-orientation.

The nature of educational reforms is outside of the scope of this article, but it is likely to include financial redistribution between academic domains, faculty preparedness, etc. This work is currently being conducted by the Ministry of Education. Encouragingly, Prime Minister Pashinyan has made his determination known on the importance of aligning Armenia’s educational sector with the ambitions and the development potential of the nation.

Reforming the domestic educational sector is a difficult task with many stakeholders and suboptimal incentive structures. Prior to 2018, due to inefficiencies on the public governance side, the approach seems to have been to hold government revenue intake in check so as to avoid public sector misallocation of resources the private sector could invest more effectively.

Hopefully, with a reduced level of nepotism and graft, and more efficient educational sector governance, the government will be able to take on a bigger and more productive role in the educational sphere.

An ideological shift is required. For years, labor education and training in the Armenian private sector in general—and in Tech/IT (incl. R&D) in particular—have been driven to a large extent by private companies themselves. Education, one of the main responsibilities of any government, was to some degree implicitly outsourced to the private sector. The idea, arguably, went along the following lines: “While the public sector is inefficient, let the private sector educate their cadres according to their proprietary needs and preferences. After all, they are the ones accumulating the profits on this labor input.” While some may still sympathize with that mindset, one quickly realizes that any expenditure borne by a private company to assume the educational responsibilities of the government will result in higher costs, lower profits and consequently, lower investment and hiring propensity. Like it or not, countries compete on labor force preparedness and quality to attract investment.

Thus, allowing the government to relieve itself of these duties and not invest in its labor force is not an approach that will result in higher national competitiveness. In fact, the data presented paints the exact opposite picture.

In conclusion, substantially higher financing on a more up-to-date, forward looking, labor market-attuned and efficient education sector is required to realize the wish of a knowledge-intensive economy.

Good outcomes from a so-called “big government” correlate with low levels of corruption and a highly-qualified public administration. With the goals and determination set out by the current government on these matters, substantially higher investment in education and R&D is both justified and encouraged.

------------------

1 - As quality of education is difficult to measure, this analysis will study the input, financing side.

2- Countries are divided into groupings in order to account for potential variations in societal/political constructs and approaches to public spending.

also read

The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Challenges in the Labor Market and Education

By Ani Avetisyan

Global trends demand new requirements in education and labor markets. To remain competitive, a country has to embark on creating, developing and implementing innovation while focusing, more than ever, on the development of a knowledge-based economy and pushing research and development forward. How will Armenia fare?

Independence Generation: Education, Societal Aspirations and Implications for Development

By Narek Manukyan

This commentary by Narek Manukyan touches upon some of the key findings about education in a study commissioned by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung called, "Independence Generation - Youth Study 2016." It takes an in-depth look at societal aspirations and how they impact youth within the context of education.

The Challenges of National Educational Assessments in Armenia

By Hayk Daveyan

While Armenia has participated in several international comparative educational assessments, and has designed national assessment tools, neither have been implemented properly. Today, more than ever, there is a great need to properly analyze existing data that can inform educational policy making and curriculum development.

Comments

Sona K

12/15/2019, 12:47:57 PMQuite much data on R&D (from science perspective at least, not sure if private R&D actions are included) is available to be requested from the Science committee. Would be interesting to see a benchmark for Armenia and if there are best examples to follow ;)

We are pleased to open up a comments section. We look forward to hearing from you and wish to remind you to please follow our community guidelines:

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.