Wed Jul 19 2017 · 10 min read

Independence Generation: Education, Societal Aspirations and Implications for Development

By Narek Manukyan

What are the concerns, aspirations, values and lifestyles of Armenia’s youth? A recent study commissioned by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and carried out by the Sociology faculty at Yerevan State University entitled, “Independence Generation Youth Study 2016 - Armenia” provides some valuable insights into the perceptions of the Armenian youth.

This commentary touches upon some key findings of the study (in terms of education) under the light of societal aspirations around education in Armenia and the implication these aspirations have on sustainable development and competitiveness of Armenia.

Controversial Aspirations

· Quality of university education in Armenia somewhat satisfies around 83 percent of students: Universities are viewed as places to socialize and mingle with peers (72.1 percent of students enjoy attending university).

· Young people, in general, do not think that possessing professional practical skills will get them jobs.

· Attending a university is viewed as fashionable and plays a key role for choosing a spouse. Once married education ceases to be a goal for around 76 percent of the youth and once divorced for around 71 percent.

· Around 50 percent of university graduates do not work in the area of their studies.

This mix of indicators, along with others outlined and analyzed below, point to the perceptions, awareness and expectations of the independence generation in Armenia

Why focus on aspirations or why they matter?

Societies are built upon perceptions and aspirations which determine, to a great extent, the role society can assume not only within the state context but also globally. In other words, sustainable development and competitiveness largely hinge on the prevailing perceptions and aspirations within a given society since they shape the human resource and capacity for innovation, impact political institutions and processes, shape the links between the economy and educational institutions. Societal perceptions reflect the ‘attitudes’ and understandings of the society in a given time and space connected to the changing contextual factors (e.g. nature of labor, mode of economy, etc.), while aspirations, to a great extent, act as mechanisms to address those changes.

The interplay between perceptions and aspirations can have rather measurable vivid outcomes in terms of state development. The perception, for instance, that possessing professional practical skills will not get one a job, but an acquaintance will, often results in an aspiration to simply get a diploma as a formal means of passing the entry barrier to the market. This aspiration, in its turn, creates a mismatch of applicants to degree programs and economic need (e.g. less in sciences, more in humanities) shaping an economy with estimated 2-3 thousand high-skilled vacancies in the tech sector.

Aspirations and perceptions are everywhere and play a crucial role also in ‘progressive’ environments which are often viewed to be less subject to such forces. Artashes Vardanyan, in his article on the mindset of Armenian startups brings some other good examples of how perceptions and aspirations shape the reality of the Armenian startup ecosystem.

Armenia is a state in transition, one that shifted from a centrally planned to a market economy via a process that envisions liberalization, economic restructuring and privatization, legal and institutional reforms towards a democratic state. The process of transition is in its third decade already, and it is imperative restate that transition is much more than a simple change in the ‘mode of economic and state affairs.’ Transition is first and foremost a change in societal perceptions and aspirations. Transition societies, as a rule of thumb, are environments of ‘contradictory social constructs’ where ‘old’ and ’new,’ local and global values and ideologies coexist and ‘compete’ within a same reality. To change the reality, societal perceptions and aspirations need to be addressed systematically.

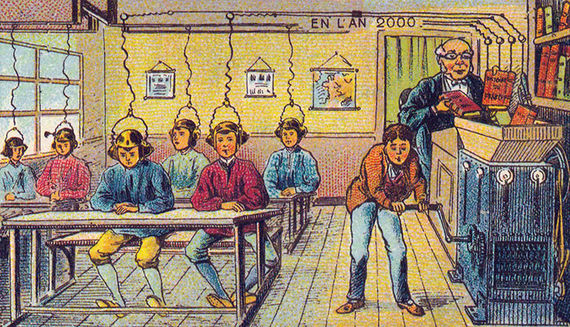

Education, in this regard, can act not only as a means of transferring certain perceptions and aspirations but also as a powerful means to address and alter those perceptions and aspirations and have a strong impact on the development of the state. Various examples starting from the education reforms in Prussia (Humboldtian education ideal for instance), introduction of the ‘peroskoulu’ in post-war Finland, introduction of the “Thinking Schools, Learning Nation” policy in Singapore, to a statement of the four pillars of learning by the Delors Commission established by UNESCO point to the role education can assume in addressing societal perceptions and creating aspirations that can lead to far-reaching impact on development.

Understanding and addressing the current perceptions and aspirations of Armenian society can lead to understanding what to focus on for the future of Armenia.

The Independence Generation in Armenia study (henceforth Study) is interesting in this regard as a ‘test’ that indicates the current societal perceptions and aspirations. It also provides room for implications for policy to address and alter those perceptions and aspirations for development and competitiveness.

What are the aspirations of Armenian youth around education?

In 1996, the Delors Commission established by UNESCO issued a report titled “Learning: The Treasure Within” for education in the 21st century where it came up with four pillars of learning (i.e. aspirations for and via education): learning to live together, learning to know, learning to do and learning to be. On a broader sense these pillars or aspirations describe the successful international education reforms and come to define the basis of international competitiveness of states (societies). Analyzing the results of the Study, in the context of the learning pillars or aspirations connected to education, reveals an interesting picture.

· Armenian youth have limited aspirations connected to the value of education: They go to university to develop intellectual abilities (26.6 percent), achieve self-realization (12.4 percent), acquire a diploma (16.3 percent), meet parental expectations (15.2 percent) and gain social status (7.2 percent). Around 60 percent of school students and around 45 percent of university students consider studies to be easy and without stress. The majority of students (around 60-70 percent) either at schools or at universities are not overloaded with lessons and spend up to three hours a day of self-practice.

· Armenian youth have limited trust towards the role of education: Around 66 percent of the youth do not consider the level of education to be a primary factor for finding a job. Young people think that in terms of finding a job, the role of the institute (practice) of an acquaintance or friend is more important than possessing professional practical skills (29.5 percent and 22.6 percent respectively).

· Armenian youth generally exchange short-term satisfaction with long-term gains: Quality of university education in Armenia more or less satisfies around 83 percent of students yet around 50 percent do not find jobs in the fields of their studies. 72.1 percent of students enjoy attending university as a means of socializing and mingling with peers. Attending a university is viewed as fashionable yet taking into account the education they have received, 51.8 percent of respondents think that they will find it difficult to get a job, while 6.7 percent do not believe that they will ever find work. Paradoxically, development of intellectual abilities and self-realization are often treated as secondary gains.

A Generation Lost or in Transition?

Public discourse often falls into the trap of extremes - we either have excellent youth or a generation lost. The reality is much more complex. The perceptions and aspirations of the Armenian youth are quite revealing of a broader picture: Education in Armenia is currently in a state of prevailing totalitarian connotations mixed with the context of some ‘democratic’ realities. The latter typically exemplifies the ‘free market’ environment where a large number of universities (60+) meet the societal demand for a diploma, schools and teachers are ‘driven’ to meet the societal demand for ‘good grades’ and education in general is viewed as a simple service. This is not surprising as transition in education at any stage includes coexistence of totalitarian and democratic connotations in varying degrees if transition in education is not addressed systematically to eliminate totalitarian connotations.

A heritage of past, totalitarian connotations in education are carried into the post-totalitarian context often subconsciously through the policy-makers and experts who have intellectually developed under the totalitarian setting. These connotations are revealed in a number of ways: in teaching and assessing mostly factual knowledge in a context of accepted connotations, in learning outcomes which entail a very limited role for personal enquiry in search of meaning, in didactic teaching, in education with neglect of enquiry into and through values and etc. Many of these may sound familiar to a student today. Totalitarian education creates limited aspirations connected to education. This does not mean that totalitarian education does not develop intellectual abilities and high-order thinking. In contrast to democratic education, development of intellectual abilities under totalitarian education is generally void of the value connotation. To put it simply - skills are not meant to serve the formulation of personal values and convictions. The role of totalitarian education is rather straightforward - inculcation of ideology and a specific set of perceptions and aspirations. The role of democratic education, in contrast, is much more complex, and it has room for human development through enrichment of values, skills and knowledge. Democratic education, in contrast, exemplifies in teachers who act as researchers of their own practice and student learning, in teaching as a form of mentoring, supervising and coaching, in learning through enquiries and values, in a redefined value and role of education for development, etc.

To sum up the findings of the Study and reflections indicated above, it is rather evident to note that:

1. Armenia is a state in transition and this, first and foremost, is a transition of perceptions and aspirations which, to a great extent, define and determine the direction of development and the role Armenia can assume globally.

2. Education can play a key role in addressing and transforming the perceptions and aspirations of the society but, as a heritage of the past, it is not generally vested with the vision to challenge individuals to a broader thinking and aspirations in individual and societal contexts.

3. Education is in a process of transition itself and rather naturally carries totalitarian connotations which have not but require to be addressed systematically.

4. Values, skills, and knowledge or in other words ‘learning to be,’ ‘learning to do’ and ‘learning to know’ are generally not perceived as chief aspirations for education.

5. The youth bear the impact of this transition in education and continuously keep pushing Armenia through repetitive cycles of transition. This will continue unless it is systematically addressed through transformation in and via education.

Implications for Policy

Continuous cycles of transition in education mean continuous cycles of broader transition including the society and economy. In other words, sustainable development and competitiveness are strongly connected to the role and quality of education in the country.

Armenia being in transition of education comes as no surprise. The limited aspirations and short-term-satisfaction that education generally provides create limited opportunities to transform to a society and an economy which can face the challenges of the current times now more often labeled as the Fourth Industrial Revolution. This becomes even more vivid taking into account that only 5.4 percent of the respondents involved in universities combine work with studies and around 31 percent of respondents neither work, nor study. Only 37.4 percent of young people studying have done internships or taken further professional qualification courses with female students being much more active.

Policy-making, various private initiatives (with certain exceptions) and public opinion in Armenia are often trapped into the thinking of short-term quantitative solutions (e.g. programs to boost certain skills such as coding, financial literacy, etc.). While these initiatives do play a role and are absolutely important for the short-term, the key implication for long-term sustainable development is that there is a strong need for targeted transformation in and through education.

Educational reform is not a one-way street, it requires balancing between solutions to problems which require quick and short-term solutions and far-reaching transformative initiatives which may not provide quick outcomes. Transformation in and through education has certain costs and tradeoffs. In essence it is a process of choosing between short-term satisfaction and long-term sustainability, between ready-made solutions and capacity-building, between political ratings and grounded work. Successful transformation in and through education have taken at least 25-30 years of committed continuous effort often at the expense of short-term satisfaction providing increased state funding (i.e. around 5 percent of GDP) to achieve large-scale results.

Education reforms in Armenia need to address problems both in the short-term as well as on the horizon to enable the transformation in and through education. Problems requiring short-term solutions do not need to be ignored, neither do the problems requiring long-term solutions and vision.

Reform policy of this type can guarantee very specific outcomes not only on a societal level, but also in the economy through building capacity and institutions for innovation and excellence, in state affairs through shaping a much more engaged and civil society. While the practice of states differ in achieving transformation, one notion is clear - solutions cannot be copied but be learnt from and designed against the backdrop of the local context and aspirations. Pasi Sahlberg in his book “Finnish Lessons” introduces the idea of “Excellence by being different” where he mainly talks about Finland shifting from the globally accepted policies in search for its own way, a transformation which took Finland around 40 years and achieved very measurable results indicating the transformation only close to the end of the third decade of reforms in the face of PISA assessment in early 2001.

To sum-up:

Loren Graham provides a striking example in his book “Lonely Ideas: Can Russia Compete,” where he writes: “The Russians kept asking us about ways in which they could catch up with research at MIT in such fields as nanotechnology, biotechnology, and computer science. An MIT administrator started talking about the ‘entrepreneurial culture’ of MIT, the commitment of even undergraduates to successful innovation…The Russians kept coming back to the technology itself. How could they develop ‘the next best thing’ in advanced technology? Finally, the MIT administrator blurted out in exasperation, ‘You want the milk without the cow!’”

Transformation in and through education is a choice in between the milk (short-term solutions seeking ‘the next best thing’) and the cow (long-term sustainability through transformation). Armenia needs to provide support not only to address short-term issues but also and possibly, primarily to create opportunities for innovative visionary programs aiming at far-reaching transformation even if the latter does not provide direct measurable outcomes in the near future.