Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, despite the mostly peaceful nature of the process itself, was followed by significant conflicts in a number of the newly independent states. War began between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh in 1992, lasting two years and reigniting in 2016 and in 2020. War also broke out between Georgia and the regions of South Ossetia (1991) and Abkhazia (1992), both of which ended with the de facto independence of those territories. Renewed tensions in South Ossetia served as the catalyst for a new war between Russia and Georgia in 2008. In Moldova, the region of Transnistria broke away in 1992 and has maintained its de facto independence since that time. Also in 1992, fighting in Tajikistan between former Communists and a loose coalition of democrats and Islamists emerged, ending five years later with a Russian-brokered truce. In Russia, Chechnya attempted to break away in 1994, achieving de facto independence for two years, only for the war to recommence in 1999, ending roughly in 2008. Lastly, in 2014, war broke out in Ukraine after Russia annexed Crimea and fomented a separatist movement in the eastern Donbass region. Overall, more than 135,000 people have been killed in post-Soviet wars, with many more displaced. Even so, almost all of this violence had an ethnic component.

This article’s scope, however, is limited to territorial conflicts in the Caucasus, North and South, each of which involve parent states seeking to stop regional populations from exercising self-determination. These are: Abkhazia, Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh and South Ossetia. While these conflicts have complex historic roots, this piece will focus on the modern and contemporary period. Even with these fairly restricted criteria, it is clear that the dissolution of the Soviet Union was not peaceful.

With the decline of the Soviet Union and the rise of nationalism across the parent states of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Russia, tensions among regional minorities, which had been marginalized during decades of authoritarian Soviet rule, heightened considerably. Minorities’ fears that their language, culture and ethnic identity were under threat were not unsubstantiated; they were based on a history of suppression by the parent states of the cultural and political autonomy of these territories and the people who inhabited them. The desire for self-preservation and its concomitant legal framework of self-determination, however, clashed with concepts of territorial integrity. The conflicts have led to the establishment of different kinds of self-rule and are, with the (arguable) exception of Chechnya, still not resolved. In the cases of Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh, it is worth pointing out that, even in the face of the uncertainty and constant existential threat that comes with the lack of international recognition, they have created functioning political systems and societies almost indistinguishable from those in fully fledged independent states.

Abkhazia

Throughout 1992-1993, Abkhazia fought a war of secession from Georgia, which killed at least 10,000 people. It came out victorious and, since the end of the conflict in 1993, the republic has enjoyed de facto independence. Abkhazia’s government is financially dependent on Russia, which also maintains a military base there with around 4,500 personnel. Abkhazia has a vibrant civil society and robust opposition political activity. There are some persistent problems in the territory, such as a flawed criminal justice system, discrimination against ethnic Georgians and high unemployment.

During the Soviet period, Abkhazia enjoyed autonomy within the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), but as the Soviet Union began to disintegrate, tensions between ethnic Abkhazians and Georgians began to grow. In April 1991, Georgia’s Supreme Soviet (governing body), chaired by Zviad Gamsakhurdia, adopted a draft on state independence, declaring the legal authority of Georgia’s 1921 constitution over the Soviet one, which left Abkhazia’s inclusion in Georgia under question. On August 14, 1992, Abkhazia made the same move as Georgia, restoring the 1925 Constitution of Abkhazia, and declared the republic’s independence. In response, Georgia nullified this decision and deployed National Guard troops to Abkhazia, starting the war.

Active warfare continued until the end of September 1993, with fierce battles in Sukhum/i, Gagra and Ochamchira. War crimes were committed against the civilian population of Abkhazia by both sides, and included the ethnically-based expulsion of Georgian civilians from Abkhazia. The fighting progressed against the backdrop of a broader civil and political conflict in Georgia between supporters of Gamsakhurdia (who became the first President of Georgia) and forces serving Eduard Shevardnadze, who headed the Georgian legislature.

The Abkhaz conflict transformed into a war of attrition with Abkhaz forces retreating in the face of advancing Georgian troops and then launching counter-offensives to recapture lost land. Aside from Abkhaz militias, Don and Kuban Cossacks as well as mercenaries and volunteers from the North Caucasus, most notably Chechen field commanders Shamil Basaev and Ruslan Gelaev, also participated in the hostilities on the side of Abkhazia.

In July 1993, Abkhazia signed a peace agreement with Georgia for a temporary ceasefire, broken by the Abkhaz, whose forces then regained control over almost the entire territory of Abkhazia. On May 14, 1994, Georgia and Abkhazia signed a ceasefire agreement. After the cessation of hostilities, the CIS’s peacekeeping force, comprised of Russian servicemen as well as military observers from the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG), were deployed to the conflict zone.

Thus, UNOMIG, in coordination with the Russian Federation, OSCE and several European countries as well as the United States, engaged in activities aimed at stabilizing the situation and reaching a comprehensive resolution to the conflict and the return of refugees and displaced persons. At the same time, little progress was made over the years. While the situation remained mostly calm, it was also tense.

The 2008 war between Georgia and Russia in South Ossetia, however, had a profound effect on the unresolved Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. After the 2008 war, Russia and a small number of other states officially recognized both Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent countries. The CIS’s Collective Peacekeeping Force was disbanded in October 2008, while UNOMIG continued its patrolling and liaising activities.

While many in Georgia have come to view the conflict as a Russian military occupation of Georgian territory, the Abkhaz challenge this, seeing increased military, economic and infrastructural support from Russia as a necessary component of their security. Ties between Abkhazia and Russia were strengthened through a strategic partnership treaty signed in November 2014, and Abkhazia has enjoyed a great deal of material improvement because of Russia, which stations around 4,000 troops there and covers more than half of Abkhazia’s government budget. At the same time, some Abkhaz elite push back on issues of sovereignty, and there are some tensions in the Abkhaz-Russian relationship.

Chechnya

The build up to the First Chechen War began with the decline of the Soviet Union, when Dzhokhar Dudayev was elected head of the unofficial Chechen opposition in November 1990, advocating for Chechen sovereignty within the Soviet Union. In June 1991, a congress of the opposition spearheaded by Dudayev established the All-National Congress of the Chechen People. A month later, it declared the Chechen Republic (Nokhchicho) to be an independent state. Sparked by the attempted Soviet coup in Moscow in August 1991, the All-National Congress of the Chechen People called for the dissolution of the Supreme Soviet of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR. Over the next weeks, it seized local government buildings and declared itself the only legitimate governing authority. In October 1991, Dudayev was elected president of the Chechen Republic. In November, he unilaterally declared the independence of Chechnya. As the separatist movement grew, demonstrations and armed clashes began to occur between pro- and anti-Dudayev factions, including several coup attempts against Dudayev. In January 1994, by a decree, the Chechen Republic was renamed the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.

The war itself began after Russia began to openly support anti-Dudayev opposition forces. In August 1994, these forces launched an attack against pro-Dudayev forces. Dudayev ordered the mobilization of the Chechen military, which stopped the pro-Russian Chechen forces from storming the capital of Grozny.

On December 11, 1994, Russia launched a ground attack against Chechnya. Many in the Russian government and military opposed the operation, and many soldiers and officers refused to take part. While the plan and expectation was for a blitzkrieg victory that would lead to Chechen capitulation, Russia was caught in a quagmire from the beginning. Yeltsin ordered the military to show restraint, but civilian losses quickly mounted, alienating the Chechen population. Because of a lack of training and experience, the Russians opted for indiscriminate carpet bombing and artillery barrages causing huge civilian casualties.

Russians began the Battle of Grozny in 1995 with a series of air raids and artillery bombardment, eventually leading to a long battle involving fierce, protracted urban warfare, killing thousands of civilians. Chechnya’s capital was eventually captured by Russian forces. After the Battle of Grozny, Russian forces moved to take the mountainous regions of Chechnya but were held back by guerrilla warfare, even despite Russia’s significantly greater military power.

The quagmire, together with the demoralization of Russian federal forces and widespread opposition of the Russian public to the war, helped end the war. After Basayev and Divisional General and future President of Chechnya Aslan Maskhadov led an operation that laid siege to Russian posts and bases, surrounded garrisons in Argun and Gudermes, causing heavy losses to the Russian forces, Russian General Alexander Lebed and Maskhadov brokered the Khasavyurt Accords on August 31, 1996 ending the war.

The First Chechen War was characterized by gross human rights violations. Russian forces engaged in indiscriminate attacks and a disproportionate use of force, resulting in many civilian casualties. Russian soldiers often stopped civilians from evacuating and they prevented humanitarian organizations from helping civilians. There is widespread evidence of Russian troops, especially those of the Ministry of Interior, engaging in torture and summary executions of separatist sympathizers as well as the rape and looting of civilians. Separatists also took hostages, kidnapped and killed Chechens thought to be Russian collaborators.

This situation characterized the chaotic two-year interwar period, during which the Chechen government’s control was weak and areas controlled by separatist forces gradually expanded. In a way, they didn’t have a chance. The lack of functioning institutions after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the devastating war left no economic opportunities for former fighters. More extremist warlords opposed the fledgling government in Grozny. After a chaotic two-year interwar period, the Second Chechen War began.

In August 1999, Islamist fighters from Chechnya led by Shamil Basayev led forces of up to 2,000 men into the neighboring region of Dagestan, declaring it an independent state. By mid-September, they were pushed back into Chechnya. In late August and early September 1999, Russia commenced large-scale aerial strikes over Chechnya, aiming to eliminate the militants who had made the incursion into Dagestan. This resulted in a large number of displaced Chechens fleeing to neighboring Ingushetia.

On October 1, 1999, Russian troops entered Chechnya again, ending the de facto independence of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, reinstating Russian rule over the territory. This time, the Russian military was joined by pro-Russian Chechen paramilitary forces, who fought against the Chechen separatists and took Grozny by February 2000. By that May, Russia had established direct rule over the territory, and the new Russian President Vladimir Putin declared the authority of Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov to be illegitimate.

This time, the Russian army moved in a slower, more organized way into Chechnya and towards Grozny. As the Russians began strengthening their presence on the ground, some Chechen separatists began defecting or being co-opted to the Russian side.

The Chechen resistance continued to inflict heavy casualties on Russians and challenge Moscow’s control over the territory for years. Chechen separatists also carried out attacks against civilians in Russia proper, drawing widespread international condemnation and marking the beginning of the international community’s previous sympathies with the Chechen side.

Over the years, the Russian government transferred military responsibilities to pro-Russian Chechen forces and ended the military phase in April 2002. The war was generally considered over by 2008. Over these years, Russian army and interior ministry troops stopped patrolling and Grozny underwent reconstruction. Sporadic violence continued throughout the region as a direct result of the war.

Nagorno-Karabakh

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan is over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh. The modern conflict can be divided into the First Karabakh War (1992-1994) and the 2020 Artsakh War. Armenians won the first war, and a tense ceasefire ensured relative calm for more than 25 years, with the exception of a four-day outbreak of fighting in April 2016, which killed approximately 350 people on both sides. Throughout this time, the Armenian Armed Forces were focused on supporting the Artsakh Defense Army (officially named the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army prior to 2017) maintaining control over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh as well as seven surrounding territories, which Armenian forces had captured in 1994. In 2020, Azerbaijan, with the backing of Turkey, launched a new offensive and regained the seven territories as well as some territory within the Soviet-era Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) itself.

The events leading up to the First Karabakh War began in 1988 when Karabakh Armenians demanded that the territory secede from Soviet Azerbaijan and join Soviet Armenia. In 1988, Karabakh Armenians, who comprised the majority of the autonomous oblast within Azerbaijan, were increasingly subjected to discriminatory policies by Baku. The Nagorno-Karabakh legislature voted in favor of uniting with Armenia. In response, strikes and protests erupted in Azerbaijan against the possible unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia, which escalated to pogroms against ethnic Armenians in Azerbaijan’s two largest cities of Sumgait and Baku in 1988 and 1990, respectively.

The already collapsing Soviet Union was caught off guard by the violence and had neither the mechanisms nor the will to ensure meaningful conflict resolution between the two groups or protect the security of civilians. The intractable nature of the competing claims and the lack of effective communication between the two sides led to population exchanges of Armenians residing in Azerbaijan and Azerbaijanis residing in Armenia amidst the start of full scale war.

Fighting was characterized by protracted mountain warfare. Toward the end of the war, Armenian forces captured districts around Nagorno-Karabakh proper as a buffer zone, which resulted in the displacement of around 700,000 Azerbaijanis from these territories, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Armenia. Around 400,000 Armenians from Azerbaijan were displaced as well. As the war progressed, Armenians shifted their aims to push for Nagorno-Karabakh’s independence.

In 1992, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group, co-chaired by France, Russia and the United States, began engaging in peace negotiations and brokered a ceasefire agreement in 1994. That ceasefire fell short of a comprehensive agreement on the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh but ensured 20 years of relative stability. The Minsk Group was ineffective at ceasefire monitoring, let alone peacebuilding for a resolution. While Armenians won the first war militarily, the lack of a final status left Nagorno-Karabakh in a state of limbo. Despite the instability, the republic built up a functioning government, a multi-party political system and elections – even without international recognition.

In 2020, Azerbaijan launched a new offensive against Nagorno-Karabakh and more limited attacks on Armenia proper, this time with direct assistance and coordination by Turkey and the Turkish military, starting the 2020 Artsakh War. This time, Azerbaijan took all the districts around Nagorno-Karabakh as well as parts of the republic itself, including Hadrut and Shushi. In November 2020, a trilateral truce was signed between Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia, allowing Azerbaijan to keep the territory it gained militarily, while Russian peacekeepers were deployed to areas inhabited by Armenians.

South Ossetia

South Ossetia is a disputed territory which declared independence in 1990, but is recognized as part of Georgia by most of the world, with the exception of five countries. Despite a ceasefire and several initiatives for peace, the conflict remains unresolved and its independence is not recognized by most other states. The conflict itself has had two active phases – the war between Georgian and South Ossetian forces in 1991-1992 and the Russo-Georgian War of 2008.

In the Soviet period, South Ossetia was an autonomous oblast in the Georgian SSR. In 1989, 66.61% of the territory was ethnic Ossetian and 29.44% Georgian. Overall, the fighting resulted in 1000 casualties and a significant population exchange, greatly shifting the demographic picture. Around half of the Ossetians who lived in Georgia moved to North Ossetia, and a smaller share moved to South Ossetia. At the same time, most Georgians in South Ossetia left for other parts of Georgia.

The war started partly as the result of a massive wave of nationalism and internal turmoil which led to Georgia’s independence in April 1991. The leader of Georgia’s independence movement, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, basing his popularity on a nationalist agenda. While he was mostly focussed against Soviet/Russian rule, it also looked down on other local ethnic minorities. With this increasingly antagonistic Georgian nationalism, South Ossetians began to self-organize and express aspirations for independence. In September 1990, South Ossetia declared its sovereignty.

After expressing solidarity with the Abkhaz independence movement, which was already underway in the spring of 1989, clashes erupted between Georgians and Ossetians in South Ossetia. In November 1989, Gamsakhurdia organized a protest of Georgians in Tskhinvali, the capital of South Ossetia. Violent clashes broke out as South Ossetians blocked the road to prevent the show of force. In the subsequent months, South Ossetians began arming themselves. By the end of 1990, ethnic tensions between Georgians and Ossetians were so high that Tbilisi declared a state of emergency in the territory. Troops of the Georgian and Russian MVD (interior ministry) were dispatched to South Ossetia, and Georgia imposed an economic blockade on the territory. In December 1990, South Ossetians voted for a South Ossetian parliament, to which the Georgians reacted by abolishing South Ossetia’s autonomous status and ultimately sending Georgian forces into South Ossetia’s capital Tskhinvali, officially beginning the war.

In January 1991, the fighting grew more intense, reaching its peak in March and April 1991. Georgians made three assaults on the Ossetian-controlled parts of Tskhinvali – twice in the spring of 1991 and once in the summer of 1992. On March 23, 1991, then-Chairman of Russia’s Supreme Soviet Boris Yeltsin met Gamsakhurdia and agreed to lead efforts to withdraw Soviet troops from South Ossetia and to create a joint Georgian-Russian law enforcement force to re-establish peace. The next day, a temporary ceasefire was set and Georgian forces largely withdrew from Tskhinvali. Violence recommenced in mid-September, when Gamsakhurdia again sent the Georgian National Guard to advance into South Ossetia.

The offensive was unsuccessful and was forced back by the South Ossetian militia. Georgia blockaded South Ossetia while Ossetians blockaded Georgian villages, during which atrocities were committed by both sides. In March 1992, Gamsakhurdia was forced from his position and replaced by Eduard Shevardnadze, who, because the war in Abkhazia had just begun, wanted to end the South Ossetian conflict and signed the Russia-brokered Sochi ceasefire. This agreement defined areas controlled by Georgia and areas controlled by South Ossetia, and it also established the Joint Control Mission, a peacekeeping organization including representation from Georgia, Russia, North Ossetia and South Ossetia. Monitors from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe were also deployed.

The military operations were described by a Danish research association as “confused and anarchic.” Military groups were often controlled by political parties and were not subordinate to their respective governments, leading to hostage taking, the targeting of civilians, as well as ceasefire violations. A 1992 Human Rights Watch report detailed acts of violence during the war, with Georgian paramilitary groups committing ethnically motivated acts of violence against Ossetian civilians motivated by the desire to expel Ossetians and to enact revenge, and several villages were ethnically cleansed by Georgian forces. On the other side, Georgians’ homes in Ossetian controlled territory were targeted for looting and arson.

The war led to a large number of refugees, with around 100,000 ethnic Ossetians fleeing Georgia and South Ossetia, settling mostly in North Ossetia, and another 23,000 ethnic Georgians fleeing South Ossetia to settle into other parts of Georgia.

A Russian-brokered ceasefire ended the war on June 24, 1992, installing a three-way peacekeeping force. This ceasefire maintained relative peace until 2004, when Georgia’s new president Mikheil Saakashvili made bringing South Ossetia back into the Georgian fold one of his aims. In 2006, South Ossetians rejected this idea in a referendum.

During this time, Russia increasingly alienated Georgia by strengthening its ties to South Ossetia, including giving Russian citizenship to South Ossetians. Both Georgia and Russia accused one another of a military build-up. In August 2008, fighting erupted again between Georgian troops and South Ossetian forces, lasting five days. Russia established control and pushed the Georgians out of South Ossetia and came close to the capital Tbilisi. Afterwards, Russia and a number of states officially recognized South Ossetia as an independent state.

The official negotiations on the conflict are called the Geneva International Discussions. Talks were first mediated by the UN, but since 2008 have been co-chaired by the European Union, United Nations and the OSCE, and include Georgian, Russian, Abkhaz, South Ossetian and American participants. Progress toward a peaceful resolution has been very slow.

related articles

Understanding the Region: Agriculture in the South Caucasus

By Hovhannes Nazaretyan

From widespread collectivization of farms during the Soviet era to privatization after independence in 1991, the state of agriculture in the three countries of the South Caucasus.

Understanding the Region: COVID-19 Response in the South Caucasus

By Karena Avedissian

More than 27 million people globally have contracted COVID-19 and almost 900,000 have died. For this installment of “Understanding the Region,” we look at how the three countries of the South Caucasus have fared in their response to the pandemic.

Understanding the Region: Energy in the South Caucasus

By Karena Avedissian

Once-integrated energy channels were disrupted with the fragmentation of the Soviet Union, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia began rebuilding their impaired energy infrastructures. How have these countries with different degrees of European and Russian influence and different energy needs and natural oil and gas reserves fared so far and what do they have in common?

Fact Sheet: The State of Democracy in the South Caucasus, Part I

By Karena Avedissian

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the three countries of the South Caucasus declared independence in 1991. This new instalment of “Understanding the Region” looks at the democratic trajectories of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Fact Sheet: What is the Eurasian Economic Union?

By Karena Avedissian

The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) was established in 2015 with the objective of creating a shared economic space with a single customs union. This Fact Sheet about the EAEU provides a closer look at its membership, it purpose, its weaknesses and more. It is part of a larger project, “Understanding the Region: The Caucasus and Beyond.”

Fact Sheet: What is the Collective Security Treaty Organization?

By Karena Avedissian

This Fact Sheet about the Collective Security Treaty Organization is part of a larger project, “Understanding the Region: The Caucasus and Beyond.” It explains what the purpose of the military alliance is, what membership entails, its weaknesses and more.

Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh

Karabakh Movement 88: A Chronology of Events on the Road to Independence

The Karabakh Movement was a crystallizing moment in the collective and historical memory of the Armenian nation. In this first in a series of articles about the Movement, EVN Report presents a chronology of the events of 1988 which eventually paved the way to independence.

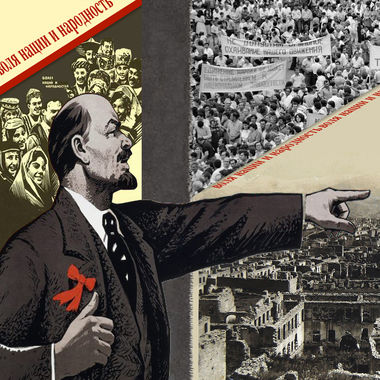

How It All Began: The Soviet Nationalities Policy and the Roots of the Karabakh Problem

By Mikayel Zolyan

Long before the first rallies and clashes over the territory of Nagorno Karabakh, there were several signs of the coming storm writes Mikayel Zolyan. One of these was the “war of memory,” waged not by soldiers, but in the sphere of historiography.

Primer: 15 Questions and Answers About the Karabakh Conflict

This primer provides the reader with an overview of the historical origins of the Karabakh conflict, the Soviet era, the war, the peace process all the way to the Four Day War in April 2016.

Implications of the 2020 Artsakh War on Regional Countries

By Hovsep Kanadyan

The 2020 Artsakh War changed the geopolitical picture in the South Caucasus, impacting all the countries in the region. While there were clear winners and losers, some countries both won and lost.

The Turkey-Georgia-Azerbaijan Regional Triangle

By Anna Barseghyan

Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan institutionalized their triangle long before the 2020 Artsakh War and have established deep roots of cooperation.

Azerbaijan’s Breach of the Peace and the Indifference of World Powers

By Zaven Sargsian

Azerbaijan’s premeditated war against Karabakh was a blow to the prevailing world order, particularly the principle that international disputes be resolved through peaceful means. The world powers must condemn Azerbaijan’s violation and mitigate the damage it has caused.