Thu May 23 2019 · 5 min read

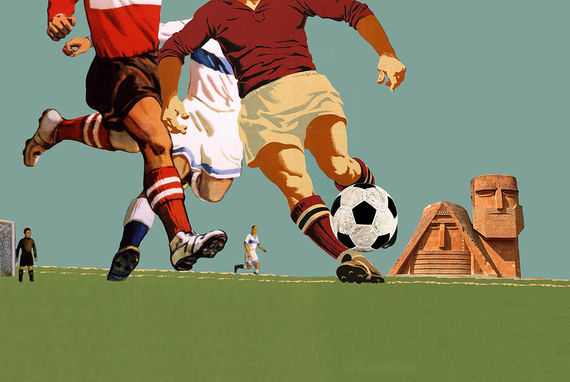

Football for the Forgotten States: Artsakh Prepares for the ‘Other European Cup’

By Joe Nerssessian

In about a week (June 1), millions of football fans around the world will be preparing for the pinnacle of the European club competition as Liverpool take on Tottenham in an all-English Champions League Final.

Yet, while Harry Kane and Mohamed Salah are fighting to be crowned champions of Europe in front of a crowd of 67,000 at the Estadio Metropolitano in Madrid, a slightly different European affair will be taking place more than 4,230 kilometres away in Stepanakert.

Squads representing Abkhazia, Western Armenia, South Ossetia, Artsakh, and a number of other sportingly isolated communities will come together for a European Cup which allows de facto independent states, breakaway regions and separatist groups to revel in the joy of playing competitive international football.

Set up in 2013, the Confederation of Independent Football Associations now boasts 54 members across the world. From territories internationally renowned for their independence fight such as Tibet and Kurdistan to the lesser-known Padania - an alternative name for the Pado Valley in Northern Italy who count Enoch Balotelli, the brother of Italy star Mario Balotelli, in their team.

Padania, the reigning European champions after victory in the 2017 CONIFA European Cup, are one of the 12 squads who will compete in Artsakh in June. The large Italian island of Sardinia and the 2018 CONIFA World Cup winners Karpatalya - a Hungarian diaspora based in Ukraine - will also take part.

Artsakh, who first competed in a CONIFA competition at the 2014 World Cup, has been a member of the organization since it was formed. Their membership partially eased the frustration which comes with being rejected for entry by the official European Football governing body, UEFA.

The team, led by UEFA Pro-license coach Slava Gabrielyan, will open the competition against Sápmi, a cultural region inhabited by the Sámi people, which stretches over Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Joining the pair in Group A is The Luhansk People’s Republic - a de facto independent state in the Donbass area of Ukraine who declared sovereignty in 2014.

“We have prepared intensively and will do our best to be among favorites. We expect to play at least in the finals,” captain of the squad Aram Kostandyan declared ahead of the competition.

He is the result of a strong heritage of football in Artsakh. In 1977 the national team became the champions of Azerbaijan in a tournament, recalls Narine Aghabalyan, the Minister for Sports and Vice President of the CONIFA Artsakh organizing committee.

“Football is one of the most beloved games in Artsakh,” she says. “You may see a lot of children playing this game in their backyards.” The global reach of football means she is hoping it could bring a renewed focus on Artsakh from the international community. “It’s important for our people,” she adds.

Gabrielyan, agrees. He sees membership of CONIFA as a way of ensuring his players get regular competitive practice. Before the 2014 World Cup, Artsakh had only played two official friendlies, both against Abkhazia. Last year Artsakh Football League was revamped, simultaneously giving players a full season of club football and Gabrielyan the opportunity to seek out the most talented players.

“It is very difficult to boost the development of any sports if you don’t have the chance to compete,” he says. “We only can compete with other teams in frames for friendly games and our trainings. Being a part of the CONIFA family, we partially solve this issue.”

Renovation of the stadia has been a key task in preparing for this summer’s tournament. More than 6000 people are expected to arrive in Artsakh during the competition, according to government estimates. The Stepanakert Stadium can host a crowd of of up to 10,000 while smaller venues in Askeran, Martakert and Martuni have also been renovated ahead of the event. Hotel rooms are already booked out across the region, leaving organizers to appeal to residents to open their homes up to visitors.

With the opening ceremony of the Pan-Armenian games also taking place in Artsakh this summer, this is an opportunity for Artsakh to show it is not just a region of conflict, says Aghabalyan. “[It] will help us demonstrate that we are talented in many aspects, such as culture, sports and most importantly we are hospitable and are always glad to welcome everybody who arrive with positive approach,” she says. “We expect visitors not only from the regions which participate in the cup but also from other countries and Armenia. This will, for sure, draw attention to our small but welcoming country.”

Of course there has been pushback of the tournament by Azerbaijan, who themselves are controversially hosting the final of the UEFA Europa League in Baku at the end of May between Arsenal and Chelsea.

The issue of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan has dominated the British footballing press in recent days as Henrik Mikhataryan ruled himself out of travelling to the final over fears for his safety. Meanwhile British supporters of both Chelsea and Arsenal with Armenian surnames have been denied visas to the match.

While UEFA has been criticized for their choice of Baku for the final, the Azerbaijani Football Federation Association condemned CONIFA for choosing to host the tournament in Artsakh. Northern Cyprus, a Turkish-Cypriot team who finished second in last year’s CONIFA World Cup, decided to forgo their automatic qualification spot over “safety fears.”

The organizing committee see the condemnation as as a regular act of protest from the Azerbaijani authorities, and believe the positives of such an event far outweigh the negatives. One quarter of Artsakh’s population is under 15 and a football team, particularly an international one, can provide alternative narrative for representing their homeland than an army uniform.

“It (the tournament) will bring more children and youngsters into sports,” says Aghabalyan, who draws on the inspiring rise out of poverty to fame by dozens of South American football stars. “The legend of football Pele was from a small town in Brazil and maybe nobody would know about him if he had no opportunity to play this game.”

“We hope that one day we will observe internationally rising stars of football who come maybe from Artsakh.”

The success of one individual would certainly bring inspiration to Artsakh, yet the ultimate aim must remain entrance to a more official arena of international football. While unlikely anytime soon, it isn’t completely out of the question. Although UEFA and FIFA’s robust policy prevents teams entering into competition if they don’t represent an internationally recognized country or territory, they admitted both Gibraltar and Kosovo in 2016 despite both being only partially-recognized.

“There is nothing impossible,” reflects Aghabalyan.“The world is changing rapidly and there are many new countries which appear on the world map and are being recognized. It depends on how consistent we will be in developing football.”

* Since the publication of this piece, four teams have pulled out of the tournament including Sardinia and Luhansk.

Also read

Taking Up the Challenge of Peace

By Armine Aleksanyan

Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister of Artsakh, Armine Aleksanyan on her long journey from Martouni to Stepanakert, to London and Vienna and back to Artsakh to work in the service of a country that is not recognized by the world

From Extreme Tourism to the First Pub in Stepanakert

By Maria Titizian

Azat Adamyan, a young entrepreneur from Karabakh (Artsakh) created a hiking club, volunteered during the April War, opened the first-ever pub in Stepanakert and now has his sights set on bigger plans. While he realizes the limits of his reality, his dreams are boundless.

The Spirit of Artsakh

By Scout Tufankjian , Maria Titizian

Photographer Scout Tufankjian has captured the essence of Artsakh (Nagorno Karabakh) through her photos. One year after the April War, EVN Report is proud to present these images as a reminder that all children deserve to live in peace.

Song Fragment for April Afternoon

By Eric Grigorian , Arto Vaun

Photojournalist Eric Grigorian and poet Arto Vaun collaborate in this piece that combines haunting portraits from the Four Day War last April with an evocative new poem.

Destination Hadrut: Arman in Uniform

By Gayane Ghazaryan

A personal essay by Gayane Ghazaryan about a trip to Artsakh to see her brother for the first time after he left for his mandatory service in the army. A day her family had always known would come but was never fully ready for. Գայանե Ղազարյանը գրում է իր նորակոչիկ եղբորը առաջին անգամ Արցախում տեսակցության գնալու իր փորձառության մասին։ Մի օր, որին նրանք սպասել են, բայց այդպես էլ պատրաստ չեն եղել։