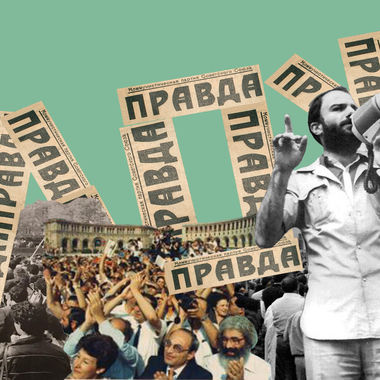

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Public spaces very often reflect the relationship between city dwellers and cities. This relationship though is influenced by multiple actors, networks and processes. Freedom Square in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital city, provides an example of how political regimes can complicate the image of a certain area by promoting their agenda, which at times can be contradicting.

Perception of “Public Spaces” in Yerevan

Yerevan, like many other cities that were exposed to Soviet urban planning, is still in the process of redefining its public spaces. Massive privatization, often only semi-legal, as well as the change of logic in urban development left the city in a chaotic state.

Yerevan still does not have a revised city development strategy, which leaves public spaces especially vulnerable. Residents have a vague perception of what public spaces are for. One of the few authors that has studied public spaces in Yerevan, Susanne Fehlings, argues that, in post-USSR Yerevan, the citizens did not really feel dramatic changes regarding the division between private and public space. The “tun” (տուն-home/house in Armenian) was the place where only the closest family members had an access to, the only place where people could feel safe during the Soviet times, as “islands of intimacy.” This situation is similar to other post-Soviet countries, like in Estonia, where Soviet-built summer houses became platforms for self-expression.

The public spaces, controlled by the state, were considered “dangerous” and unknown during the Soviet period. This did not immediately change after Armenia’s independence in 1991. Communists were replaced with the new state elites in Armenia, tightly connected with business. Now public spaces were associated with the new elites, while ordinary citizens still felt alienated in them. The state-people dichotomy remained. There was a clear division between private and public. I do not necessarily agree with Fehlings’s view, since I believe that, in independent Armenia, political regimes bring their own agenda regarding public spaces, which is definitely different from how the situation was during the Soviet period. Political regimes keep shaping and re-shaping public spaces with their political goals and agendas, influencing the perception of public spaces. I will try to show this with the example of Freedom Square, but I will first present a general brief review of the situation of public spaces in Yerevan.

Public areas, including parks, green areas, squares and underpasses, some of which are now privatized in Yerevan, still continue to be the main platforms for civic and political association in independent Armenia. The “Mashtots Park” movement in 2012, which saved a park in the city center from being turned into a shopping area, was a strong starting point for the forging and activation of civil society in Armenia. The activists of the “Mashtots Park” movement later on engaged in other mass movements, such as “We Pay 100 Drams” (against the increase of public transport fares in Yerevan), “I’m Against” (against pension reform), “Save the Afrikyan Building,” and “Electric Yerevan” (against the increase of electricity prices). The activists who had been involved in these social movements appeared at the forefront of the “Velvet Revolution.” Some even then took on positions in Yerevan City Council, the National Assembly and government ministries.

Freedom Square as a Symbol of Democracy

Freedom (or sometimes Liberty) Square, which is also called Opera or Theatre Square, since it is adjacent to the Opera and Ballet Theatre of Yerevan, is one of the main central squares of Yerevan. In 1988, Freedom Square served as one of the main gathering points for the Karabakh movement. The square was closed down several times by the Soviet authorities in an attempt to block protests.

Since then, the square became a symbol of democracy, and it has been the place where opposition groups and political parties would usually organize their rallies and protests. When it became clear that Levon Ter-Petrosyan had manipulated the results of the 1996 presidential election, people assembled at Freedom Square to voice their protest. Eventually, Ter-Petrosyan resigned in 1998, mainly because of his stance on the Artsakh issue.

In the 2008 presidential election, Ter-Petrosyan faced off against Serzh Sargsyan, who was Robert Kocharyan’s appointed successor. This time, it was Ter-Petrosyan who was on the losing side of election fraud. His supporters gathered at Freedom Square, with some protesters setting up tents and spending nights at the square. They were demanding a recount. The protests started on February 20, 2008. At first, President Kocharyan did not take them seriously, urging the protesters to leave the square and calling it a “theater.” Protesters did not obey, which ended up in the police and army forcefully dispersing them on the morning of March 1. There were 4,000 people that spent the night at the square. Several protesters were injured and taken to hospital. Some people who were not protesting, but just happened to be nearby, were also beaten by the police. Protesters relocated near the statue of Alexander Myasnikyan across from the City Hall building, close to the embassy buildings of France and Italy. Ter-Petrosyan claimed that he was not allowed to join the protesters. It was on the night of March 1, when the well-known events took place. The police and army attacked the protesters, as a result of which 10 people were killed; two of them were policemen. After these events, the privatization of the green areas and public spaces surrounding the Opera building continued at an even faster pace than before, making Freedom Square smaller and smaller. This can be viewed as an attempt by the authorities to diminish the significance of the square as a gathering point for opposition groups, and to make it a leisure area full of cafes and other entertainment establishments.

After the 2013 presidential election, Freedom Square was again the gathering point for the opposition, this time led by Raffi Hovhannisyan, leader of the “Heritage” Party.

In the spring of 2018, the Velvet Revolution was led by Nikol Pashinyan, who was a member of Levon Ter-Petrosyan’s team in 2008. The movement was aimed at not allowing Serzh Sargsyan to take up the role of Prime Minister, extending his reign beyond two presidential terms through constitutional reforms. However, Freedom Square was not used as the main gathering point. Protests were occurring all over the country and Yerevan, with local people participating actively. These tactics proved to be successful, mobilizing hundreds of thousands of people, with the focus on Republic Square. This way, they did not associate themselves with previous failed attempts that were based at Freedom Square.

Post-Velvet Revolution Developments

A snap parliamentary election took place on December 9, 2018, where Nikol Pashinyan’s My Step Alliance won 70 per cent of the votes cast. The Velvet Revolution was complete, with many civic activists becoming Members of Parliament (MPs) and being appointed to various roles in the executive branch.

With the transfer of so many activists, NGO representatives and media outlets to the state sector in Armenia, it does not come as a surprise that the new officials initiated reforms aimed at bringing about changes in various spheres, including urban planning and development. The newly-elected Yerevan City Council members, led by Mayor Hayk Marutyan, started removing advertisement banners around the city center, mainly focusing on the area near the Opera Theatre and the Swan Lake next to it. However, the most dramatic events occurred after Yerevan City Council decided to start the process of reclaiming the space at Freedom Square.

The City Council announced in December 2018 that the cafes surrounding the Opera House would be demolished in the spring of 2019. Following the announcement, the owners of the cafes were sent official notifications on February 13, 2019, informing them that they should remove all their furniture and equipment by March 13, when the demolition work was planned to start. It should be noted that the owners of those cafes were associated with the pre-“Velvet Revolution” political class. Nevertheless, by March 13, only one cafe owner had vacated the premises. The remaining cafes simply did not remove any furniture or equipment. Instead, they mobilized their staff-waiters, cooks and cleaners to protest against the City Council decision. They stated that they have contracts with City Hall until the end of 2026. They argued that their cafes make Yerevan authentic; they represent the culture of the city. Moreover, they claimed that they had taken out business loans, and that changing terms on them midway threatened Armenia’s business climate. (State authorities later investigated and found that no business loans were actually outstanding.)

Following these actions, only three cafes were demolished, citing that only those three had clear problems with documents which allowed the authorities to proceed with the demolition. Most of the cafes still continue to operate today. This led to disappointment in the actions of the new municipal authorities of Yerevan by residents, architects and activists. Freedom Square did not change its image. It is unclear what the main goal was, since they did not convert the area into a larger public space, being unable to demolish the remaining cafes, claiming that there are ongoing court cases against them.

Freedom Square again became the center of political activities after the 2020 Artsakh War. It does not come as a surprise that the November 10 ceasefire was met with extreme criticism by the Armenian public. Leaders of 16 political parties joined their forces and proclaimed themselves an opposition, even though only three had participated in the previous parliamentary election, and only one had seats in the National Assembly. They demanded the resignation of Prime Minister Pashinyan and the creation of a transitional government. Freedom Square served as the main gathering point for this group of protesters since November 2020 (before they moved to Baghramyan Avenue in mid-March). The organizers set their numbers at 4,000-5,000 participants. Among them are supporters of Robert Kocharyan, who called the square “theater” back in 2008. The three main political parties behind the movement, the Republican Party of Armenia, Armenian Revolutionary Federation and Prosperous Armenia Party were part of the governing coalition, when protests at Freedom Square were brutally crushed.

Freedom Square is one example of how politics crafted the image of a public space in the minds of residents. It has complicated associations and is generally still alienating for people. In two cycles, groups viewed as oppressors have returned to it to speak out against oppression. Rarely has the exercise yielded results. It stands in a transitory state, half-reclaimed but unable to be transformed. It is a public space but serves private profits. Both a symbol of democracy, it is called Freedom Square after all, and a reminder that we are not there yet.

also read

Karabakh Movement 88: A Chronology of Events on the Road to Independence

The Karabakh Movement was a crystallizing moment in the collective and historical memory of the Armenian nation. In this first in a series of articles about the Movement, EVN Report presents a chronology of the events of 1988 which eventually paved the way to independence.

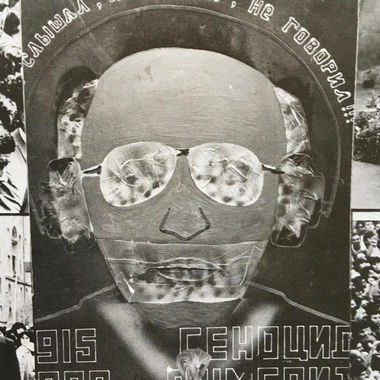

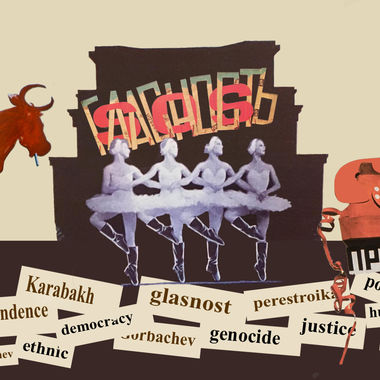

The Slogans, Posters and Language of the Karabakh Movement

By Harutyun Marutyan

One of the distinctive characteristics of the Karabakh Movement was that in less than three years, it drastically changed how the Soviet value system was perceived. The visual and verbal manifestation of this was evident through the transformation of the language and texts of the posters and signs used during the Movement.

1988

By Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan

In this exceptionally honest and candid article, Gevorg Ter-Gabrielyan writes about his impressions from the first few months of the Karabakh Movement 30 years ago, with words he did not have nor could find at the time.

A Country That Changed Hands: A Conversation About Us and Us

By Lusine Hovhannesyan

Lusine Hovhannisyan was a witness and participant in the Karabakh Movement. Thirty years later, she had the chance to meet with someone who was on the opposite side of the barricades - a Soviet official who had tried to infiltrate the ranks of the demonstrators.

Is 2018 the New 1988?

By Mikayel Zolyan

In this new piece, Mikayel Zolyan writes about the similarities and differences between the 1988 Karabakh Movement and the 2018 Velvet Revolution - what it meant for people then and now and lessons to be learned.

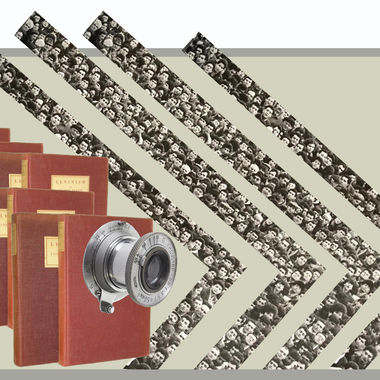

Portraits From Republic Square

By Eric Grigorian

Photojournalist Eric Grigorian's series of portraits from Republic Square where thousands gathered in protest as Yerevan enters the seventh day of mass rallies, protests and innumerable acts of civil disobedience.

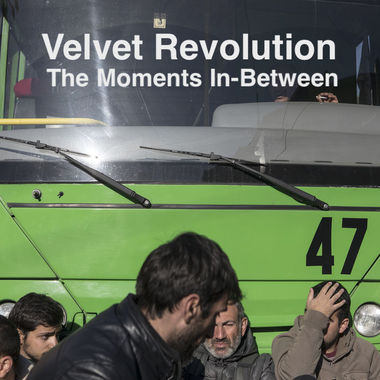

Velvet Revolution: The Moments In-Between

In 2018, the Armenian people were swept up in a nationwide movement that would come to be known as the Velvet Revolution. Photojournalist Eric Grigorian took thousands of photos, documenting and capturing images of ordinary people who came together to achieve the extraordinary. Through his own words, Grigorian tells the story of the revolution and the moments in-between.