Sun Apr 15 2018 · 7 min read

The Slogans, Posters and Language of the Karabakh Movement

By Harutyun Marutyan

This article is the second instalment of Harutyun Marutyan’s "The Karabakh Movement or What was Happening in Soviet Armenia 30 Years Ago."

In 1989, social and political upheavals shook one Eastern European country after another, something historians would later characterize as “Eastern European Revolutions” or simply the “Revolutions of 1989.” The Berlin Wall, in the heart of Europe, which had symbolized the dividing line between the “democratic” West and the “communist” East, came down. With this, the socialist camp disintegrated; within two years the Soviet Empire disappeared from the world map; the ghost of communism, roaming in Europe from the times of Marx and Engels was confined to the pages of history and merely became the subject of study. A year before these developments, a powerful democratic movement began in the smallest of the Soviet Republics, in Soviet Armenia. In academic literature, with a few exceptions, it is considered only within the context of what was seen as an “ethno-territorial” conflict, an Armenian-Azerbaijani one. In my opinion, what took place in Armenia as part of the Karabakh Movement, was the first of the Eastern European revolutions and as such, played a considerable role in the democratization of Soviet society, had a substantial part in the deconstruction of the Soviet Union and consequently the elimination of the threat of communism. As the first, it was not regarded or perceived as a revolution, and as such, remained obscure in academic circles, whereas the formulations of the “unrecognized revolution” can shed new light on the study and evaluation of democracies that emerged in Eastern Europe in the late 20th century.

One of the distinctive characteristics of the Karabakh Movement was that in two and a half years, it drastically changed how the Soviet value system was perceived. The visual and verbal manifestation of this was evident through the transformation of the language and texts of the posters and signs used during the Movement.

In general, images and slogans are among the most palpable expressions of national identity, and as a rule, they appear during times of crises and accompany revolutions, mass national gatherings, radical changes in the life of a county; sometimes alongside processes that can last years. Often, as direct indicators of the the popular mood, or sometimes having been created by political forces, signs contain an enormous wealth of information about the era allowing a clearer understanding of the times. These are unique knots of identity where many different threads are pulled together and concentrated. Unraveling the unique microcosms of those knots allows one to view macrocosmic phenomena. Posters, as visual “testimonials” of social processes, usually immediately echo the changes of a situation, making it easy to follow the steps of social developments through posters and through an analysis of their contextual changes to follow the transformations of political orientation and identity. In this regard, the Karabakh Movement offers a large and rich field of study.

What is distinctive about the posters created during the Karabakh Movement is that an overwhelming majority of them represented not so much the agendas of certain parties or political currents but the concerns, moods, wishes and evaluations of people regarding certain developments. If during the Soviet era posters carried the ideological stamp of the ruling party and were strictly regulated and ruled out any divergence, the posters of the Movement incorporated a wide variety of genres, had contextual diversity and ideologically stemmed from a nationalistic as well as Soviet construct. In other words, the visualizations were direct indicators of the public’s liberated mindset.

They were often also manifestations of archetypical national thought. At the beginning of the Movement, this was explained by the fact that the verbal information - political speeches delivered during the protests, the discussions - were not supplemented with a visual presentations, because in their programs and reports, the Soviet television and press did not fully reflect the situation and in their evaluations of the unfolding events, an intentional bias was noticeable.

Under these circumstances and aside from being the visual representation of the Movement’s struggle, the posters also took on the function of a free press, greatly contributing towards the political education of the masses and a qualitative change of identity. During the years of the Karabakh Movement, in person-authorities-society-state relations, the posters were those intermediaries and unique tools through which the mindset of people and society were transferred including also their appeals to the ruling authorities and the evaluations given to them.

The posters were addressed not only to the ruling authorities, but also to the Armenian people, the Hayastantsis, the Azerbaijanis, all the citizens of the large Soviet state, the world - in other words to everyone who was interested in issues concerning Armenians. The posters were a unique monologue of the people, with the hope of transforming it into a dialogue. In this way, they were equal to dozens if not hundreds of interviews, polls...by analyzing the texts of the posters it was clear how the process of expelling Homo Sovieticus from inside hundreds of thousands of people was taking place.

Let's try to illustrate the above with a few examples. Radical changes in attitudes took place:

Concerning the central media outlets of the USSR

Concerning the USSR Constitution

Concerning the Central Committee of the Soviet Union (ԽՄԿԿ)

Concerning the Soviet judiciary

Armenians’ centuries-old faith in the Russian people and the Russian soldier as a savior was shattered

The need to combat Russian cultural assimilation was realized

It was understood that ideology of the international, unbroken friendship of the people of USSR was hollow

The value of the Armenian peoples’ unity was realized

The belief in working independently was understood and grew exponentially

In other words, ideas conditioned by external and internal factors, being born at the bottom, matured and gradually encompassed nationwide involvement.

Of the national-democratic movements and revolutions in the former territories of the USSR, the Armenian Revolution was the first. Confronted with opposition from the state apparatus, many things were developing autonomously in Armenia, however, within the framework of existing laws. It is for this reason that I don’t rule out that the knowledge gained from researching the Armenian Revolution, can and does propose new, perhaps nuanced factors in the study of contemporary revolutions.

As a rule, every new phenomenon has its uniqueness, knowledge of which can provide new clarifications while studying events that proceed it. The Karabakh Movement or the ‘unrecognized’ Armenian Revolution until today, has not been considered a research area in the contemporary theory of revolutions neither in Armenia or elsewhere; a comparative analysis of similar events that took place in the USSR or Eastern Europe has not been addressed. This is one of the issues confronting Armenian social scientists.

I reserve the right to express the opinion that the Karabakh Movement was an indicator of how the small Armenian nation, at the end of the 20th century rose up against the most powerful Soviet Empire and won, not with power, but with democratic national values fomenting such a revolutionary wave that it led to the fall of the Berlin Wall and sent the fear of communism into the pages of history.

All images are from H. Marutyan's personal archive or his book, “Iconography of Armenian Identity-Volume 1: The Memory of Genocide and the Karabakh Movement.”

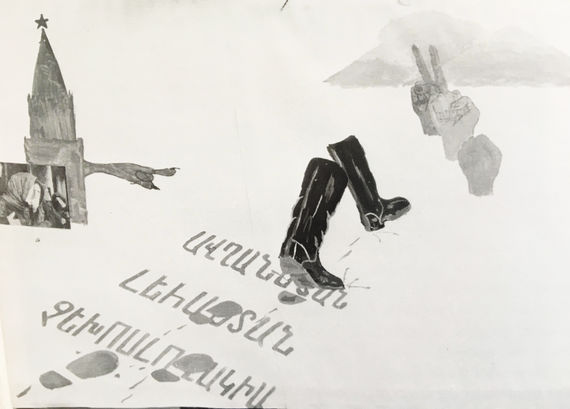

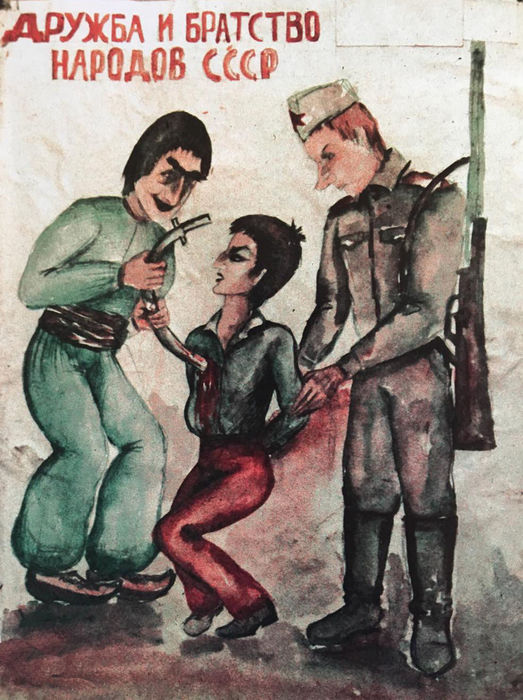

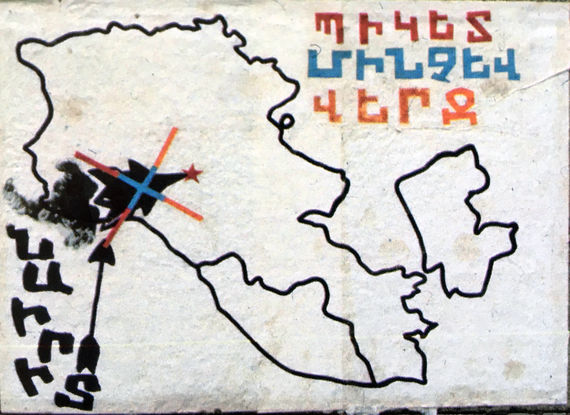

Concerning Armenians’ faith in the Russian people and the Russian soldier as a savior.

Moscow-Yerevan, 1988.

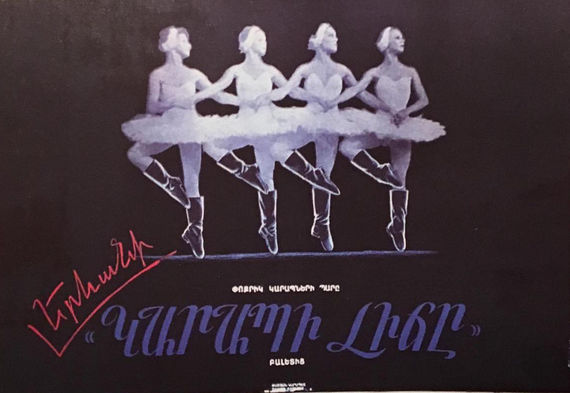

Yerevan, Swan Lake, "The dance of the little swans."

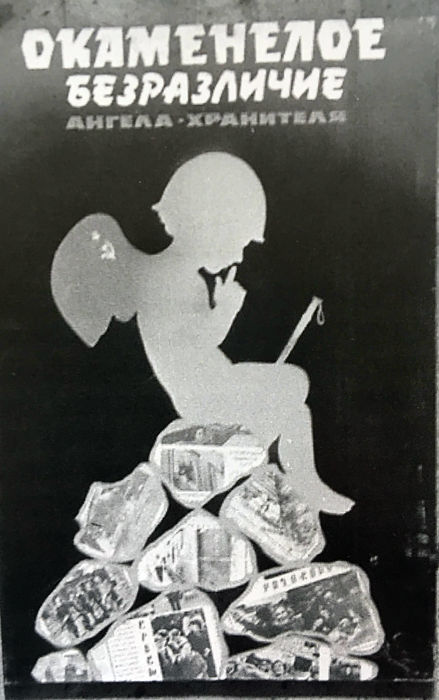

"The deadly indifference of the guardian angel."

"But these are our children..." A reference to Gorbachev's response to a Soviet soldier being injured during clashes in Yerevan.

Czechoslovakia, Poland, Afghanistan.

"Friendship and brotherhood of the USSR nations."

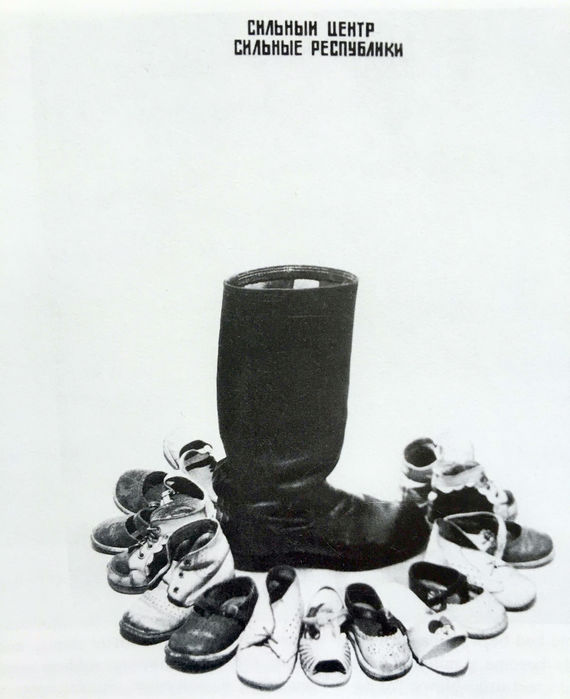

"The strong center of the strong republic."

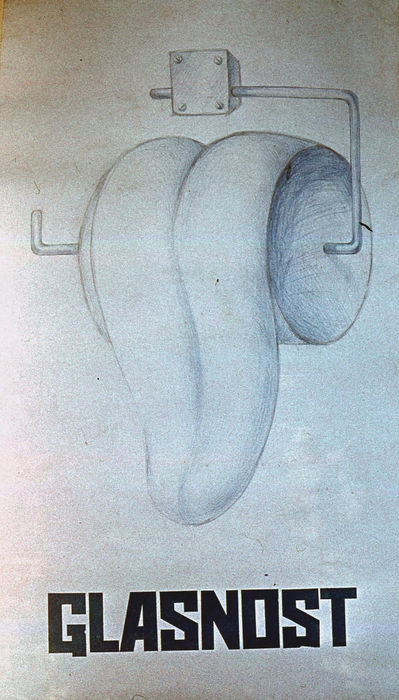

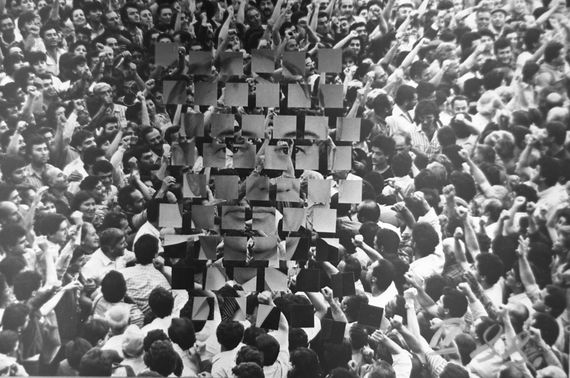

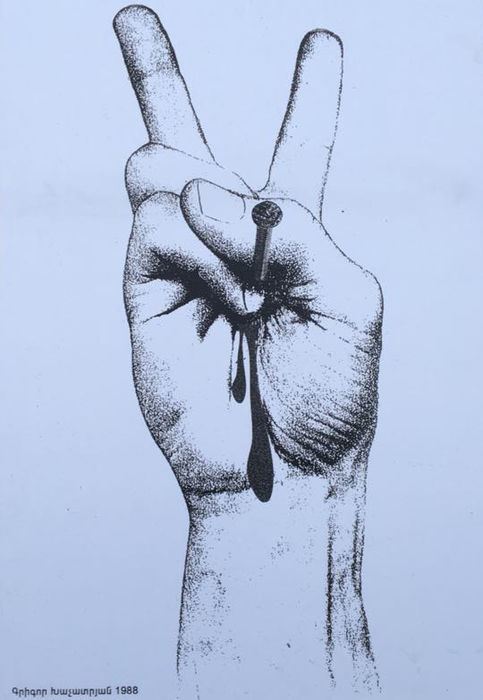

Concerning the USSR Constitution and Gorbachev's Glasnost and Perestroika.

The sleeves read, "Democracy, Perestroika, Glasnost," the Rubic's cube reads, "Artsakh."

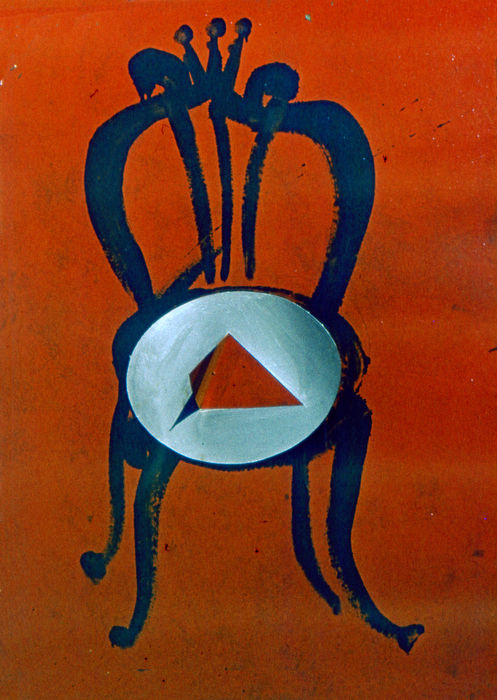

"Party and nation are one." The word "Nation" is designed to be hanging from the letters of the word "Party."

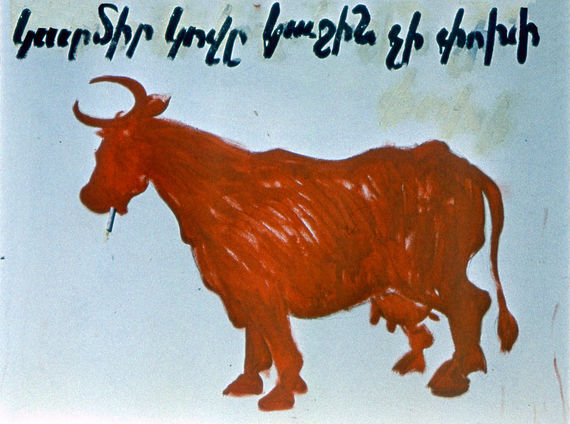

"The red cow will not change her skin."

The Constitution.

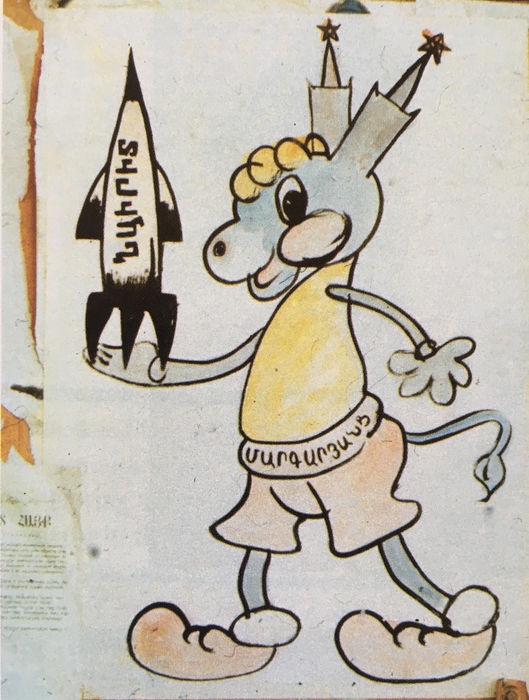

A political caricature depicting Gorbachev. On the ballon is written "Perestroika;" the suitcase reads, "Democracy, Glasnost."

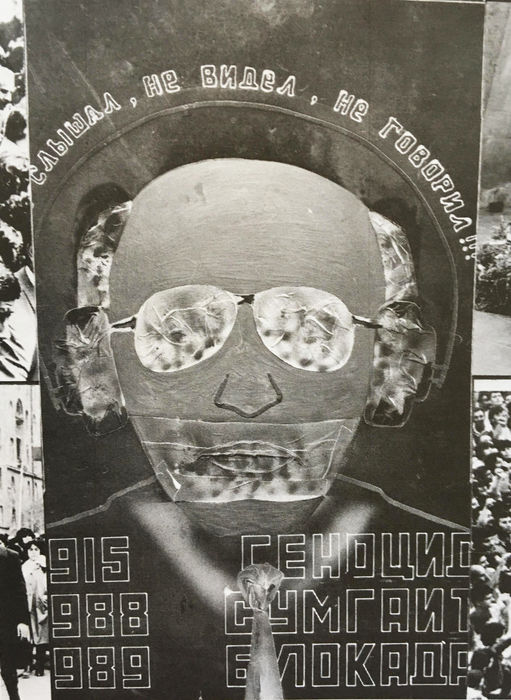

"Did not hear, did not see, did not speak," Gobachev - 1915: Genocide, 1988: Sugait, 1989: Blockade.

The word Constitution in Russian that is brought down to a single letter "я" meaning "I".

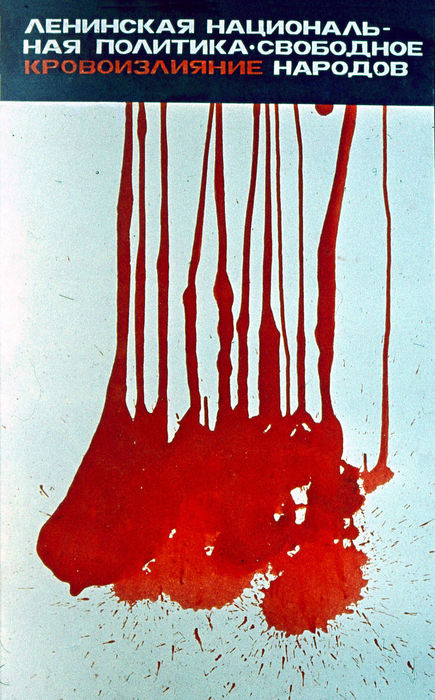

Lenin's national policy: Free BLEEDING of nations.

Glasnost.

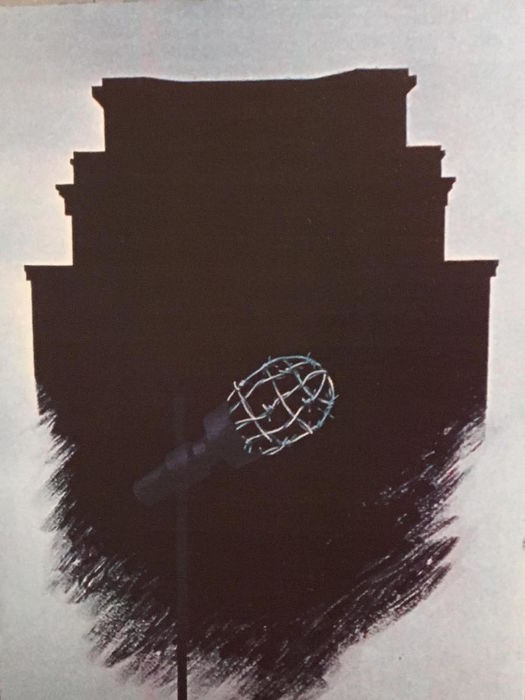

Concerning the central media outlets of the USSR.

In reference to the opening credits, "Time Forward" of main TV news program Vremyan (Time), but changed to read, "Time backward."

A scarecrow made of diffrent newspapers - Pravda, Izvestya, Communist.

The word "Presssss" pressed between two telephones and a copy of the Pravda newspaper.

Concerning the Soviet judiciary.

Concenrning the environment.

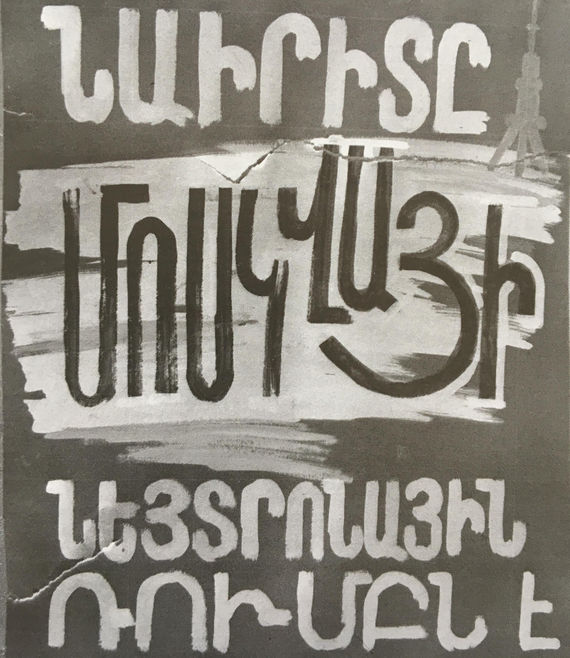

"Nairit is Moscow's nitrogen bomb."

Nairit.

"Nairit: Picket to the end."

Others.

The arrows read: "Unity," "We Demand," "Strike."

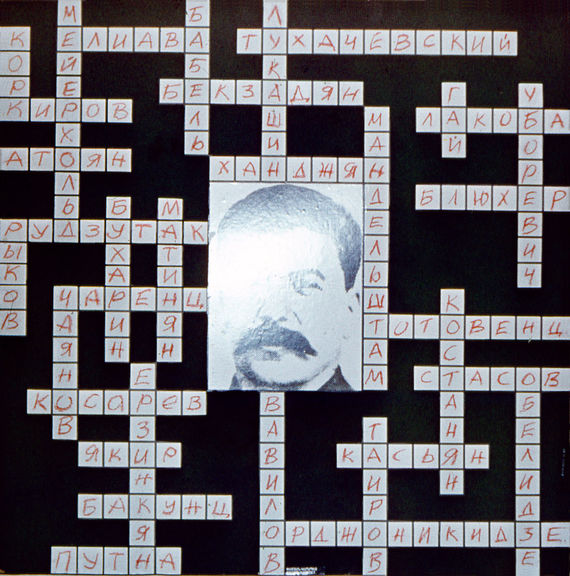

A crossword puzzle with the names of Stalin’s victims.

EVN Report wishes to thank the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES) for their cooperation and support.