Tue Jun 01 2021 · 8 min read

Seeking Permanence in Pixels: Digital Echoes of Cultural Genocide

By Roza Melkumyan

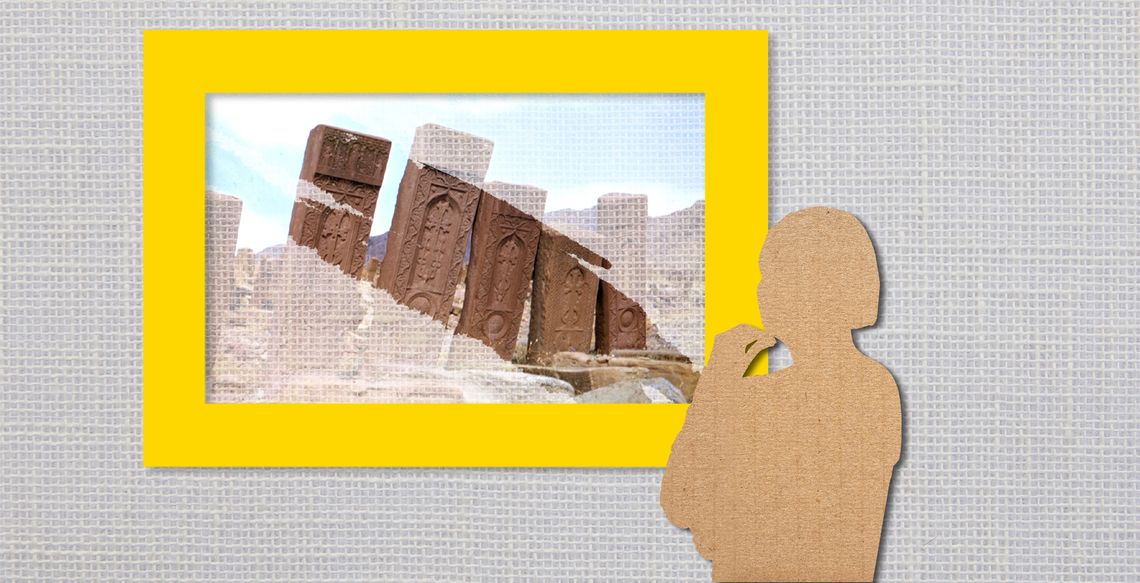

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

According to Wikipedia, “Paraga is a village in the Ordubad District of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, a landlocked enclave of Azerbaijan. Its population of 306 is busy with gardening, vegetable-growing and animal husbandry. It has a secondary school, library and a medical center.” A small, remote village, it isn’t on anybody’s radar. Except mine.

I discovered only recently that this unimpressive village was the home of many of my Armenian ancestors. In its second and final section, Paraga’s Wikipedia page features a short paragraph detailing the Armenian monuments that once existed in the village. “In the center, there stood the domeless Surp Shimavon Church, and in the countryside, the Surp Hakob monastery complex, both of which dated back to the 12th and 17th centuries.”

These sentences do not validate the testimonials of my distant relatives, who say this was our home. They don’t have to. To be gifted with such specificity in family history would be a miracle, considering all that we’ve lost to war, to destruction, to the malevolence of our oppressors.

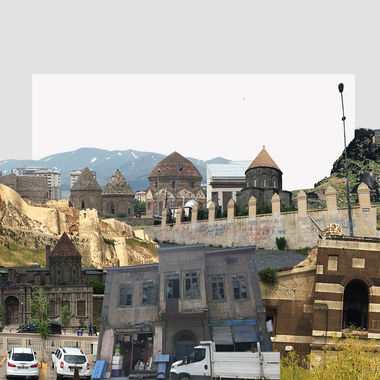

Armenia today boasts over 4,000 churches and monasteries in its cities and countryside. The Armenia of antiquity, covering a much larger territory, boasted thousands more. But as neighboring empires seized and conquered our land, killing and expelling Armenians in the process, those monuments fell to ruin, either from neglect or destruction. Who can say for sure how much of our physical culture has been lost forever? Churches and monasteries might be a dime a dozen in modern-day Armenia, but none hold such a high place in my heart as do those of Paraga. Their memory chronicles at once the presence and the absence of my family, of the Armenians of Nakhichevan.

After Nakhichevan was transferred from Soviet Armenia to Soviet Azerbaijan in 1920 by decree of the USSR, its Armenian population began relocating to Armenia. By the start of the First Karabakh War in 1988, the rest were expelled. After the war, the borders of Nakhichevan, as well as Azerbaijan Proper, were officially sealed to them forever.

What knowledge I’ve collected on my Armenian family history has come slowly and in slivers, like tendrils of water trickling down through cracks in the ground. As I grow to identify more with my Armenian heritage, I receive this information like a sponge. But as a child, I was solid rock. Born to a Tatar mother from Uzbekistan and an Armenian father from Azerbaijan, I was raised in a mixed-ethnicity Soviet household. Though I was acquainted with the Russian language, with our Apostolic Church, and with the various Western Asian dishes my mom would cook, I did not care to learn about my Armenian history. I attribute this attitude principally to the strained relationship I had with my father, whose specific brand of stubbornness had always clashed so bitterly with my own. An obstinate child who could only perceive her culture through its association with her father, I distanced myself from my Armenian side.

Of the bits of information that did manage to permeate my rock-like resolve, I remember the magazine the most. After unearthing it from some trove hidden among stacks of books and papers in the home office, my father laid it proudly before me: a National Geographic magazine dating back to March 2004. He flipped through until he landed on the bookmarked section: “The Rebirth of Armenia,” a 10-page feature on the history of Armenia, from ancient times to Genocide to the First Karabakh War.

As disinterested as I was, I recognized that my father valued this magazine. He handled its weathered yet still-glossy pages as though they might disintegrate in his hands. It wasn’t until much later in my life, when I decided to actively connect to my Armenian heritage and move to Armenia, that I understood why. Printed in a world-renowned publication, these pages acknowledged us when entire nations hadn’t.

Almost every Armenian can say that their ancestors were killed, displaced or otherwise negatively impacted by the Genocide. My family is one of the few that cannot. No, our trauma is fresher. To my father, that article was not just history; it was his life. He—along with much of the Melkumyan family—was one of around 500,000 Armenians who lived in Soviet Azerbaijan prior to the outbreak of the First Karabakh War in 1988. The Baku Pogrom of 1990 would displace him forever.

As a child, I mistook my father’s fixation on the pages of that article as an indicator of pride and vanity. As a young adult, I understand it as a manifestation of the validation they gave him. Somebody had told his story, at least in part. It would not be lost.

The girl who had overturned that story like the pieces of a puzzle she had decided was not interesting now finds herself scrambling to collect those pieces. As I scan the Wikipedia page of the village of my ancestors, greedily searching for some nugget of information that might tell their story, I understand my father. As my collection of information grows, and as my search for more fills the space at the forefront of my consciousness, a sadness settles in. The Armenians who called Azerbaijan home may never return. Apart from the fact that they are banned by Azerbaijani law, the general public of the country has been taught by their government to hate us. My father speaks often and fondly of his life in Baku, of his days eating caviar out of the Caspian Sea with a spoon, of his family’s apartment building. He can never return.

If it wasn’t painful enough to know that I can never visit the old homes of my relatives, it was plenty to realize I could not visit those of my ancestors either. When I learned that our family came from Nakhichevan before emigrating to Azerbaijan in the late 1920s, my heart lifted, then sank. Here was a new piece of information for me to add to my archive. But here was also a piece of information that would plunge me into the tragedy of its history.

Since the First Karabakh War, the Azerbaijani government has engaged in the destruction of Armenian monuments in a quest to erase all evidence of our culture. In its subsequent denial that such sites ever existed, it has tried to erase our memory too. They had started their plunder in Nakhichevan, destroying the Armenian cemetery in Julfa and its 10,000 funerary monuments and khachkars (uniquely-decorated Armenian cross-stones), replacing it with a military shooting range. They destroyed churches, monasteries and monuments to our culture. Like Azerbaijan, Nakhichevan existed on a plane which we could never reach.

Though the Armenian monuments of Nakhichevan, of Paraga, had long been destroyed, I at least had some shred of their memory. My father had found our history preserved in print; I had found it in pixels. We clung to sentences which had us believe that we inhabited at least a small space of a collective consciousness.

Fast forward to October 2020, in the midst of the 2020 Artsakh War, now acknowledged to have been instigated by Azerbaijan, despite initial news reports lending credence to Azerbaijan’s denial of that fact. Not a day went by that we did not do some sort of volunteer work to help the war effort. In the break between shifts sorting clothing for displaced families one day, I paid another visit to Paraga’s page. Though I had read it a dozen times already, I scanned its contents once more, hoping I might find some new scrap of information hidden in the lines.

“Paraga is a village in the Ordubad District of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, a landlocked enclave of Azerbaijan. Its population of 306 is busy with gardening, vegetable-growing, and animal husbandry. It has a secondary school, library, and a medical center.”

That was the whole article.

I stared at my screen in disbelief. The second section about the Armenian churches was nowhere to be found. Frantically, I searched for something on the page that might restore what had been lost. I learned quickly that each Wikipedia page has an easily accessible edit history. Scrolling through time to the moment my history was erased, I found him: a user who went by the name of Shahin085. His listed reason for deleting our history?

“Typo.”

One of the first things we learn in elementary school English is that Wikipedia is not an acceptable source to cite for research papers. Though valuable in the sheer breadth of information it contains, the online encyclopedia depends on volunteer contributors from the general public. Even with its own special editing system in place, errors and malicious edits can find footholds.

I was fascinated, but I was also scared. Any physical remnants that might have preserved the memory of my ancestors and the Armenians of Paraga had been eradicated ages ago. If even the Internet showed no trace of their existence, then who was to say that they existed at all? If it was so easy to write us off as a typo, then wasn’t that initial evidence worthless to begin with?

Last November, we lost the war. We lost much of Artsakh (Karabakh). With it, we lost towns and villages and the monasteries, churches and other monuments within. Now they sit, vulnerable, in the hands of those who want them destroyed. As I write, Azerbaijan has already dismantled the spires of Shushi’s Ghazanchetsots Cathedral, scrubbing the land clean of our memory. In the wake of this fresh destruction, the tragedy of Nakhichevan echoes.

Paraga has become everything to me. Sometimes I wonder, if I speak its name often enough, if I spell it out, write it on the walls, can I will it—its Armenian history—into that collective consciousness? In a world that becomes more digitized daily, what of the physical remains? What of the digital can be accepted as truth? Am I a fool to think that a paragraph detailing the Armenian monuments of some small village somewhere can give the record of our story any real permanence? It only took a second to delete.

A few weeks after its disappearance, the coveted paragraph was restored to Paraga’s Wikipedia page by a different user. Reason given? “Reverting malicious edits [removal of sourced Armenia-related content] probably connected to Azerbaijan’s ongoing invasion of Artsakh.” I’d like to say I was relieved to see the information returned, but I am left paranoid beyond belief. I feel a fool for thinking either I or my father could place our faith in pixels and print. Call us a typo and we are deleted. I visit the page often, just to check, ready to restore what was lost.

also read

Christianity in Karabakh: Azerbaijani Efforts At Rewriting History Are Not New

By Hratch Tchilingirian

In the context of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the “Albanian connection” has become a politicized issue of irredentism, hijacking the rich Christian heritage of Karabakh. The roots of this historiography go back to the Soviet policy of “nativization".

A Conceptual Gap: The Case of “Western Armenia”

By Varak Ketsemanian

“Western Armenia” as a concept is a crucial component of the Armenian national narrative, mostly in the Diaspora. In this article, Varak Ketsemanian raises some questions regarding the Armenian reality’s understanding of “Western Armenia,” its biases and blind-spots. He suggests refining the ways in which we discuss and represent “Western Armenia” in the 21st century.

The Eternal Minority?

By Paul Mirabile

Armenians scattered globally share one very prominent reality: they represent a minority status, writes Paul Mirabile arguing that the Armenians' numerical “weakness” has forged a most extraordinary but, at the same time, a most tragic reality.

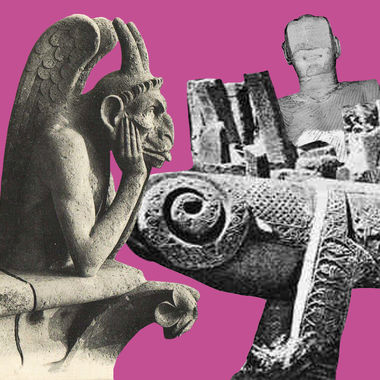

Notre Heritage? The Uncomfortable Truths of Cultural Legacy in Peril

By Vigen Galstyan

The fire that severely damaged the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris highlighted how indispensable art is for humanity and exposed the fragility of all cultural legacy. It also indicated the profoundly unbalanced ways through which the global community has come to evaluate the intellectual production of different cultures and nations.

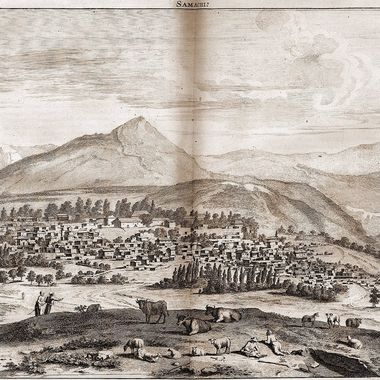

Shamakhi: A Lost Dialect, a Lost Identity

By Narine Vlasyan

Shamakhi is an Armenian dialect that is on the verge of extinction. While many Armenians from Shamakhi feel a sense of pride in their history and dialect, for the new generation who, along with the rest of the Shamakhetsis were forced to flee their village during the Karabakh War, the dialect is simply a matter of history.

Also see

Magazine Issue N4 / PAST