Sun Sep 05 2021 · 8 min read

Impact Metrics to Help Revitalize Armenia's Libraries

By Laurie Alvandian

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Lusine is a 37-year-old mother of three living in Yerevan. She doesn’t work, leaving her entirely financially dependent on her husband, who is physically abusive toward her. Last summer, she started taking the kids to visit her cousin, who works at the city library. Her husband allowed it, thinking that she couldn’t get into too much trouble there. Soon, Lusine started taking the kids to the library more often. She liked that it was quiet and calm, an escape from the violent chaos at home. Since everything at the library was free of charge, she didn’t have to ask her husband for money for each visit. The kids could play and read, and she could think in peace. The city library is old; there are very few places to sit, and most of the books are from the Soviet era. Nevertheless, the days when she visits the library are when she feels the safest.

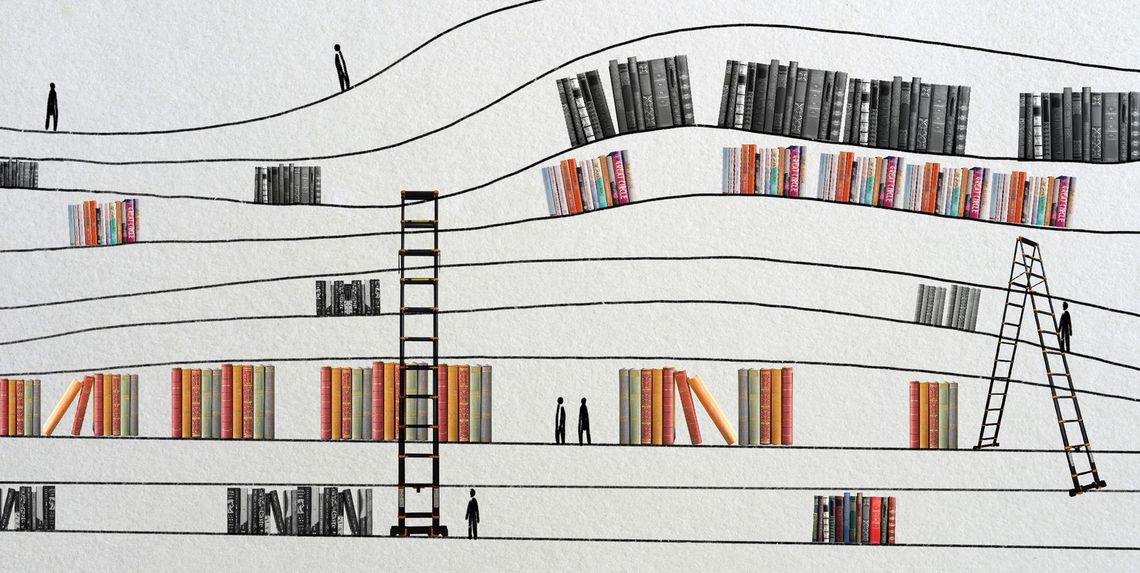

Like Lusine, there are millions of people around the world whose experience of using the library is deeply personal. Without talking to them, however, it can be difficult to measure the impact of the library on an individual. Traditionally, the go-to method for many librarians has been to look for volume—program attendance numbers, monthly item loans, or registered patrons. But these numbers do better at measuring library usage, rather than impact. It is also important to measure depth—that is to say, how far does the library’s impact stretch into not just the life of the community, but the life of the individual user?

Usage metrics provide numbers from which we can assume impact. If 20 people attend a library workshop on media literacy, but only five people attend a workshop on poetry writing, is it safe to assume that the media literacy workshop had a greater impact? Not necessarily. Let’s say one of the poetry workshop attendees was introduced to a piece of poetry that essentially saved his life. He had been struggling with depression and suicidal thoughts, but was greatly helped after discovering poetry as an outlet for his mental health issues. In this case, the impact is immeasurable. Not only were new skills learned, but a life was saved. It’s precisely these types of personal and individual impacts that usually fail to show up when looking at library statistics. We use traditional data to justify the expense of keeping libraries running. But why don’t we use stories of impact, which are far more telling and meaningful?

Christian Lauersen, Director of the Roskilde Public Library in Denmark, took on this challenge. In February 2021, his library published an innovative new study titled “The impact of public libraries in Denmark: A haven in our community.” The goal of the study was to further understand the reach of library services on individual users; to understand not only how many times they used the library, but in what ways those experiences impacted their lives. To do this, the library identified four dimensions of impact: haven (users can immerse themselves and experience well-being), perspective (the library gives users perspective on life), creativity (the library allows people to develop creatively), and community (the library helps form and maintain communities). They then applied those dimensions to four types of library services: the collection, the events, the physical facilities, and staff guidance. The data was gathered from a nation-wide survey of a representative sample of citizens in Denmark between the ages of 16-90.

Not surprisingly, the results showed that the library impacts users in a diverse range of ways. “Haven” scored the highest, meaning people placed a strong importance on the library as a comfortable, welcoming and credible communal space. “Perspective” came in second, suggesting that libraries play a big role in intellectual development by making available resources that are curated for the local and global landscape. “Creativity” and “community” followed. “The study shows that four out of five citizens believe that public libraries still have relevance today, despite the rise of digital services such as Spotify and Netflix, and this is also linked with the finding that the vast majority of citizens in Denmark believe that public libraries are important because they offer free and equal access to knowledge and culture—online entertainment is not free and equal—and the impact of libraries being places of trust. In an age where it is difficult to distinguish information from misinformation, it is of great importance to citizens that the public library curates and disseminates knowledge and information—physically and digitally,” explained Lauersen.

But one of the more dramatic discoveries of the study came from the “non-users,” or people who generally do not use the library. The study found that 82% of present non-users have previously made use of the library. In other words, only 18% of non-users indicated that they have never used a public library before. This corresponds to roughly 6% of the Danish public having never used a public library. Meanwhile, 40% of those current non-users believe that it is likely or very likely that they will make use of a public library sometime in the future. In fact, only 3.5% of the Danish public can be defined as absolute non-users, meaning they have never used the library before and never will in the future. These are powerful numbers when trying to gain an understanding of how far impact stretches into Denmark’s population. It’s safe to say that the vast majority of the population of Denmark has been positively impacted by the library in some way, because now the data exists to clearly back up that claim.

Unfortunately, Armenia’s public libraries are nowhere close to being able to offer the types of public services, programming and resources as those in Denmark. In fact, aside from moderate physical renovations, investment in Armenia’s libraries has been relatively stagnant over the past 30 years. The biggest effort that can be pointed to came in 2015, when then-Mayor of Yerevan Taron Margaryan ordered the renovation of 36 of the city’s libraries with the goal of adding new books and computers, and attending to major structural needs. More recently, the ANI Armenian Research Center announced that it was launching a program to replenish the books of over a hundred rural libraries, some of which haven’t received new books in decades.

Every year, the National Library of Armenia collects and publishes statistics on Armenia’s libraries, using metrics such as number of existing libraries, book collections, loans, registered users, library visits and number of employees. The most recent data suggests that, in almost all categories, numbers are down from the previous year—all except the number of registered users, which increased by over 12,000. The demand for library services and spaces may be growing, but libraries across Armenia still lack the proper tools to answer that demand.

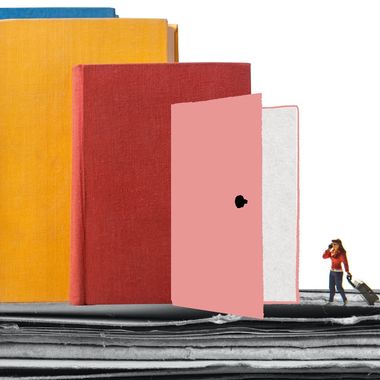

While the 2015 round of renovations was one small step (and let’s not forget, only concentrated in Yerevan), it’s unclear whether any sort of assessment was carried out to measure the impact of those new changes. If it had, it might have inspired a shift in the conversation about why libraries matter, and what practical and sustainable steps need to be taken to ensure everyone in Armenia has access to a great one. One of the rare nationwide assessments related to reading and libraries was done in 2012 under the Book Platform Project funded by the European Union, focused on reading habits in Armenia. Aside from the alarming statistics on their decline, the assessment found that young people are unlikely, in both cities and towns, to access print materials from their libraries, seeing them as antiquated and inaccessible. Both the young and middle-aged demographics reported a desire for modern libraries and bookstores that have friendly staff, thematic shelving, a designated space for reading, and a broader selection of e-materials.

What seemingly hasn’t been addressed yet is the future of Armenia’s libraries. The current approach seems to be less about sustainability and more about temporary survival. This practice has led to a situation in which, year after year, more and more libraries are quietly shutting their doors for good, leaving thousands of people without access to basic resources or opportunities for intellectual development. Sustainability for Armenia’s libraries can only be achieved by first taking an honest and thorough examination of what we want the country’s libraries to represent, what role we see libraries and librarians having in society, and how dedicated we are to catching up to global standards. In other words, are we prepared to seek out, cultivate and advocate for the support needed to create a library system that is on par with the ones found in a place like Denmark?

Moving forward, Armenia needs to look to data as a tool for adopting a more sustainable model of support for its libraries. Imagine a country in which all libraries used curated, community-specific metrics of impact and health to measure not just the impact of the library, but also to identify what precise need within the community that impact came in response to. For instance, if data shows us that a particular region in Armenia has higher rates of domestic abuse than others, libraries could respond by focusing their efforts on designing programming, services and resources that tackle that specific issue. Then, impact metrics like those used in the Denmark study could be used to measure the degree to which those efforts had an effect on the community. With data available as proof of the library’s contribution toward building healthier communities, it becomes harder to justify not investing in them. It’s entirely possible, of course, that the lack of assessment is purposeful—a tactic to avoid having to confront uncomfortable truths and accept the fact that the existing systems aren’t working and aren’t serving the needs of the country.

For a library system like Armenia’s, which hasn’t been significantly updated in 30 years, implementing a major systemic change would require a complete overhaul of our already-established perceptions of what libraries can offer, and what impact they can have. Eric Klinenberg, an American sociologist who has written extensively on the impact of libraries in society, poses this question in his book Palaces for the People: “Why have so many public officials and civic leaders failed to recognize the value of libraries and their role in our social infrastructure? Perhaps it’s because the founding principle behind the library—that all people deserve free, open access to our shared culture and heritage, which they can use to any end they see fit—is out of sync with the market logic that dominates our time. (If, today, the library didn’t already exist, it’s hard to imagine our society’s leaders inventing it.) But perhaps it’s because so few influential people understand the role that libraries already play in modern communities, or the many roles they could play if they had more support."

The concept of looking at libraries through the lens of both usage and impact could potentially usher in a new era of support, financial and otherwise, for Armenia’s libraries, and reverse their trajectory from outdated book repositories to impactful centers of community development. In the end, how do we put a dollar amount on the impact the library had on Lusine’s life? Or on someone struggling with mental health issues who needed the opportunity to discover a new outlet? These cases are not anomalies. They’re everywhere, hiding behind the numbers we so often look to to justify the costs.

Also See

Armenia’s Post-COVID Tourism Development Prospects

By Hranoush Dermoyan

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the tourism industry hard globally and Armenia was not spared. Another obstacle hindering development prospects for tourism in Armenia is regional and border stability which will also play an important role when travel resumes in full force.

Who Benefits From Comfortable Workplace Environments for Mothers and Babies?

By Astghik Karapetyan

Having a designated nursing room at the workplace and flexible working conditions help working mothers to continue breastfeeding after returning to work, keeping the emotional bond between mother and baby uninterrupted․

Children and War Trauma: “We Have to Stop Lying to Them”

By Astrig Agopian

Suren says if he had a magic wand, he would change people to make things better. Children of the 2020 Artsakh War continue to struggle with trauma. A center in Kapan is trying to change that.

Emergency Medical Care: How Anticipating Catastrophe Makes a Difference

By Dr. Sharon Chekijian

Armenia is now in a teachable moment. It is time to double down on disaster preparedness and emergency care development by taking proactive measures and moving from reaction to prevention and mitigation.

The Myth of “National” Science

By Gagik Tovmasian

The current state and future direction of science in Armenia has been discussed on various platforms recently. Gagik Tovmasian writes about the need to elevate the status of national institutes and willingness to open up to the world.

Fixing the Cracks: Building in an Earthquake Zone

By Hovsep Markarian

A 4.7 magnitude earthquake rattled Yerevan back in February. Although it didn’t cause significant harm to people or structures, it triggered the inescapable question: Can Armenia withstand another major earthquake?

By the Same Author

Houses of Democracy: Why We Need to Fix Armenia's Crumbling Libraries

By Laurie Alvandian

Modern libraries are anything but purely warehouses for books. They are people, ideas and lifestyles blending into each other. When well-funded and nurtured, they are the most democratic institutions we have today.