Mon May 17 2021 · 7 min read

Houses of Democracy: Why We Need to Fix Armenia's Crumbling Libraries

By Laurie Alvandian

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

My first library card was yellow and made of thick cardstock. To receive it, I had to sign the back with my signature, which, at five years old, resembled little more than a scribble. The librarian told me that I could take home up to 40 books at once—an unthinkable amount for me at that age. But I slid the card into my back pocket and wandered into the children’s room of my local New Jersey public library. I didn’t realize it at the time, but that card defined my life—as a human, a citizen and a future librarian.

In the library, I learned that the world is filled with many ideas and that, if I didn’t pay attention, I could get swept away by the wrong ones. I learned that the world does not revolve around my own thoughts, but rather that all ideas are connected, like a collection of small streams leading into an untamed river. I learned that I was part of a team, and that all around me—in the world, in my community, on the shelves of the library—were invisible teammates that I had yet to meet. But most importantly, I learned that I knew nothing. There is always more to learn; it’s an infinite process, not a finite one. This revelation laid out before me an important choice: I could either participate in the process of creating myself and my surroundings, or I could close my eyes and stumble my way to the end. I was lucky enough to have that choice, because for many the decision is already made for them the day they are born.

The concept of participation—in the development of one’s self, one’s community or one’s nation—is a necessary ingredient of democracy. For Armenia, democracy is a fairly new practice, limited, in most of the population’s mind, to the act of voting. But a healthy democracy demands more than just a trip to the ballot box. It requires a wide range of actions, all of which culminate to form a population informed enough to vote. Voting is therefore the result of democracy, not democracy itself.

To have a truly healthy democracy, you need an informed citizenry, an army of individuals who, regardless of circumstance of birth, have free and unobstructed access to the resources they need to become better and more educated humans. Information breeds action, movement, energy. An uninformed citizenry, by contrast, is an idle, confused one, unable to take stable steps forward. What we currently have in Armenia is something closer to a performative democracy—an expertly crafted illusion in which hardly anyone is given any tools, and yet told they can build a country.

The idea that libraries have some role to play in the strengthening of democracy is one not yet normalized in Armenia, in part because the majority of people, including many of its librarians, still think of libraries as purely warehouses for books. Official reports published by the Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia in 2018 state that 733 libraries exist (161 in urban areas and 572 in rural areas), defining libraries as places “with universal book stocks serving demands of the public for publications.” This definition alone highlights the limited cultural perception of libraries. Many of these libraries lack basic necessities like electricity, bathrooms, new books, comfortable furniture or computers. Moreover, the absence of modern library science education has meant that many librarians remain detached from both ideas of what it means to perform their job in the 21st century, as well as the needed environment and tools to do so. Physically, operationally and culturally, Armenia’s libraries have been neglected since the country’s independence some 30 years ago. Whatever small advancements have been made can be attributed to the motivation of its librarians, coupled with occasional international funding.

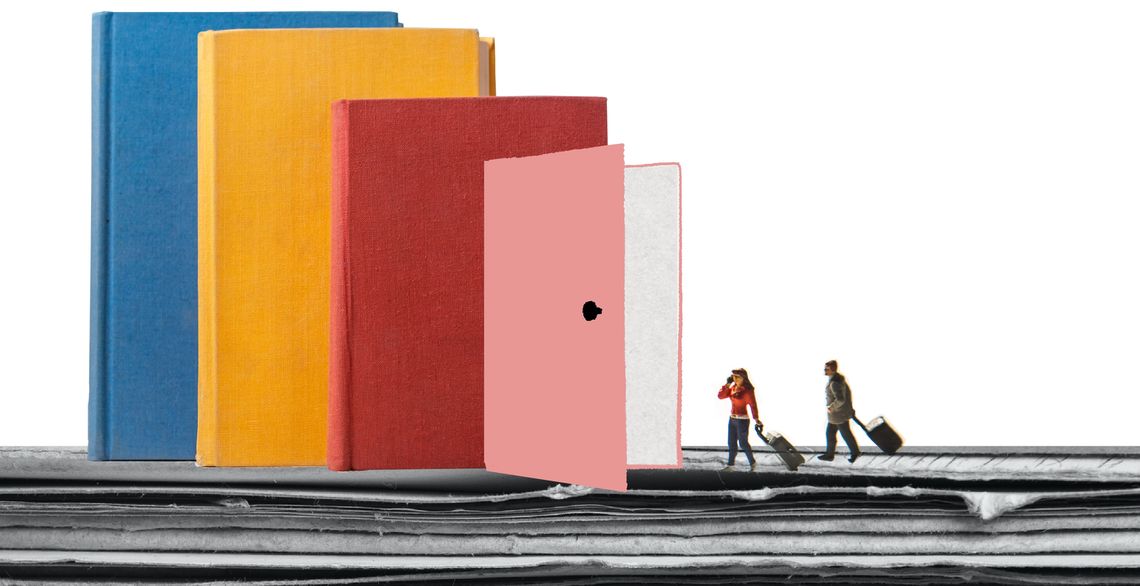

In reality, modern libraries are anything but warehouses. They are people, ideas and lifestyles blending into each other. And when well-funded and nurtured, they are the most democratic institutions we have today. Digital skill-building workshops, resources for refugees and new citizens, maker-spaces, community gardens, bilingual storytimes—these are the types of activities that build communities and democracies. In 2014, the Aspen Institute compiled a report on their vision for the future of libraries. Taking into consideration global trends in library use, the 35-member working group concluded that libraries are built on three key assets: people, place and platform; and that they must act in four main ways: aligning library services in support of community goals, providing access to content in all formats, ensuring the long-term sustainability of public libraries, and cultivating leadership. If we look at all the ways libraries are being used today, it’s obvious that they can no longer be perceived as relics from the past, but rather vibrant community spaces for envisioning and creating the future.

When we use a public library, we learn to care for a space we all share. We enter into an invisible social contract that says “everyone here is equal, everyone here deserves access to information, everyone here deserves an opportunity to develop their mind, and I, as a library user, am participating in that process.” Not surprisingly, the simple act of using the library gives people the exact same skills necessary to participate in democracy. We learn to think beyond ourselves, and we realize that our individual success is linked to the success of our neighbors.

We live in an information-saturated era, and the ability to not only access that information, but also learn to navigate and wield it, is vital for the development of critically-thinking minds that will hold their elected representatives accountable. When every person, from the richest to the poorest, has free public access to information, you create inclusive and equitable societies and democracies. You give everyone the tools and the vocabulary they need to formulate their thoughts and express themselves, both in their daily lives and in the voting booth. When one’s resources are limited, so is one’s worldview. And in the case of Armenia, its citizens have been wading in a stagnant swamp for decades, falling behind and being left out of the local and global conversation.

Armenia ranks 89th in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2020 Democracy Index, being categorized as a “hybrid regime,” just one notch above an authoritarian one. If we attempt to measure Armenia’s democracy a different way—by looking at its libraries, and specifically its public libraries—we start to see that Armenian democracy and its libraries share the same characteristics. Both are crumbling, underdeveloped and full of cracks. If, instead of building yet another shopping center, we invested our efforts into human capital via holistically redesigning Armenia’s libraries, we would simultaneously be sustainably developing our communities and our democracy. As we move closer to national elections, the future government’s decisions regarding the nation's libraries will be a clear indicator of their intent to either progress toward, or regress from, a truly democratic future.

Globally, countries that boast a greater number of public libraries and professional librarians are associated with higher literacy rates, higher levels of social cohesion and generally more equal societies. For Armenia and other developing countries with high levels of poverty and poor public education, well-funded public libraries armed with professional librarians can serve as impactful lifelines for communities that desperately need to fill in rampant educational and social gaps. In Serbia, for example, Belgrade City Library provides training on using basic financial tools, while in Romania, over 400 public libraries helped 17,000 farmers access government portals to obtain agricultural subsidies that brought back over $20 million into their communities.

Of course, libraries cannot solve every problem plaguing society, nor do they seek to. But they do have a proven track record for strengthening community and democracy. A 2019 American study suggests that living near community-oriented public spaces results in increased trust, decreased loneliness and a stronger sense of attachment to where we live, regardless of whether it’s in a city, suburb or small town. The study also concluded that “residents of amenity-packed neighborhoods are more likely to say their community is an excellent place to live, to feel safer walking around their neighborhood at night, and to report greater interest in neighborhood goings-on.” When citizens feel a sense of agency in the development of themselves and their communities, they are far more likely to actively participate in the continued success of those things.

The tired argument that libraries are archaic, irrelevant institutions not worthy of public funding can be debunked the moment you look at the data. A massive 2016 Pew Research Center survey showed that about half of all Americans above the age of fifteen used a library in the past year, with two-thirds of respondents claiming that closing their local branch would have a “major impact on their community.” What would happen in a country like Armenia, where community needs are so great and so varied that a well-funded public library in each community would have a hard time running out of ideas on how best to help?

What could be the impact for communities whose entire economies depend on agriculture, but who lack access to resources on modern farming techniques or online markets? Or for victims of domestic abuse who need a non-threatening place to seek refuge or access resources on receiving help? Or for young adults who receive no sex education in school but want to learn about their bodies? Or for students who feel overwhelmed by a flurry of digital information and want to defend themselves by learning about media literacy? Or for adults who didn’t go to college but want to learn a new skill for free?

Regardless of whether or not everyone uses the public library, they undoubtedly still benefit from it. A community in which every person has access to the resources they need to better themselves and pursue an independent education creates a better society for everyone. When you participate in democracy, you don’t just support the things in which you directly benefit from, you also have to show up for the things your neighbor needs.

After a devastating war, continued rampant poverty and simmering civil unrest, Armenia’s future may seem uncertain. The stability its citizens seek can only come from the ground up, with informed and empowered individuals equipped with the tools they need to build their ideal country. Armenia’s libraries can and should lead the way in launching the nation toward a true democracy—one in which everyone has the means to participate.

From our archives

literature

When More is Less: Love and Cement in Revolutionary Yerevan

By Christopher Atamian

Christopher Atamian reviews “The Structure is Rotten, Comrade,” a new graphic novel by Viken Berberian and Yann Kebbi.

The Eternal Magic of Mariam Petrosyan’s Gray House

By Lilit Margaryan

Translated into several languages, Mariam Petrosyan’s epic novel “The Gray House” has enchanted readers across the world. In this first book review, Lilit Margaryan speaks with the elusive Petrosyan about her life and the life of a novel that took 18 years to write.

Thoughts on (not)Editing

By Tatiana Ryckman

In her piece on (not)editing Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s new novel “The Brick House,” author and editor Tatiana Ryckman says that Marcom's fiction changed her reading and writing life forever.

The Importance of Difficult Steps

By Aram Pachyan

The translation of prose or poetry is not a news headline or a tweet, it is a piece of literature that demands time, contrasting thoughts, artful concentration and the ability to publish, writes Aram Pachyan.

A Room of Our Own: An Invitation to Write

By Atoussa S.

Atoussa S. explores the history of women writing and their absence in the literary canon. In this essay for EVN Report, she seeks answers to the questions: What circumstances make women writing/literature possible? What do women own in their writing? What is the meaning of this ownership?

Women Who Write

Armenian women writers have largely been forgotten or ignored. Their essays, poems and novels have either never been published or have been left out of the literary canon. Here is a selection of covers written by Armenian women over the past decade.

The Terrain of “Living” Western Armenian Literature

By Vartan Matiossian

Western Armenian literature does live in many different environments, traditional or innovative. The question, however, is in what conditions or with what prospects? New pathways are necessary to keep it “living.”

Comments

Hasmik Galstyan

5/18/2021, 7:07:30 AMWonderful article! Thank you, dear Laurie, for sharing your thoughts, good research, and positive attitude towards libraries. Yes, The Library is the gate to A2K, Information literacy, knowledge-based confidence in building " true democracy."