I read Petrosyan’s book in my early 20s while pursuing my Master’s degree at Lomonosov Moscow State University. When people at my faculty found out I was Armenian, they would invariably ask with excitement if I had read the novel, “The Gray House,” taking into consideration that the author was Armenian.

When writer Mariam Petrosyan published “The Gray House” in 2009, it became an instant bestseller. The book was shortlisted for the Russian Booker Prize in 2010 and won Russian Prize for the best book in Russian by an author living abroad. It felt as though everyone was talking about the book and the magic flowing from its pages.

Although I happened upon Petrosyan’s novel several times in the past, my arrogance prevented me from reading it. Back then, during my teenage years, I was the kind of person, who was deeply fond of classical literature and always felt suspicious of any kind of contemporary books. However, my Russian friends were very persuasive. Thus, in the fall of 2012, I started to read it. It took me approximately two weeks to finish the almost 800-page epic novel brimming with ethereal magic and a twisted reality.

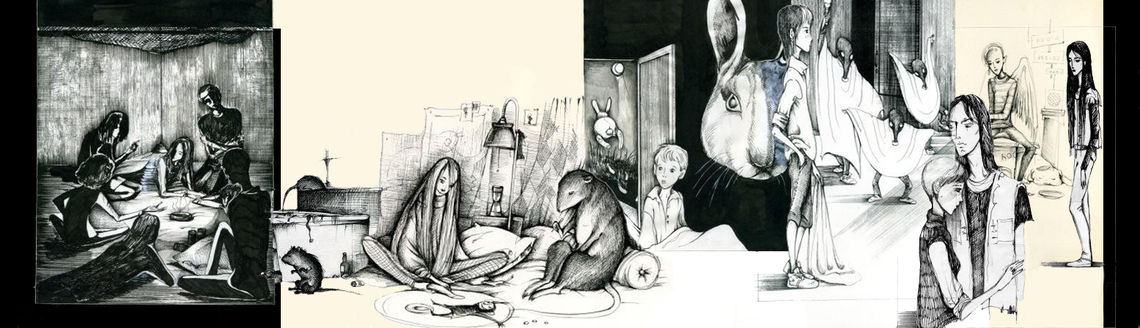

“The Gray House” from the very first page gives you an uncanny sensation that you are reading a book which has an unearthly quality of telling the truth. It felt as miraculous and truthful as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and The Little Prince combined together in the vastness of Hogwarts. The book has no storyline. All actions take place in a gray house, which is located on the outskirts of town. The house serves as a boarding school for children with various disabilities. The place is wayward interregnum full of teenage protagonists with the peculiar philosophical assumptions of reality. Although the place and the characters living in it seem to be beyond reality, while reading you are haunted by the thought that Petrosyan has created a modern maquette of society which thoroughly depicts the flaws and virtues of real human beings. This book gives you both the emotional and intellectual satisfaction of magical realism.

I was captivated and astounded by it. I couldn’t help my disappointment when I found out that it had not yet been translated into English. I wanted the whole world and especially the English-speaking Diaspora to read it. Imagine how happy I was when a year ago, on April 25, 2017, the long-awaited English translation of Petrosyan’s cult saga came out thanks to AmazonCrossing.

In its review, The Guardian has described the English edition of the novel as “enigmatic and fantastical, comic and postmodern, flawed but brilliant, with elements of multiple genres – Rowling meets Rushdie via Tartt.”

When I saw the English version, my first thought was to find Mariam Petrosyan and request an interview. After several unsuccessful attempts looking for her contacts, I gave up. Besides, I was told that she doesn’t like to be interviewed. People do not know that this only increased my desire to talk to her. In my mind, I compare her with such famous reclusive geniuses of contemporary literature as Donna Tartt and Elena Ferrante who give interviews only once a decade.

I had almost forgotten about my intentions, when several weeks ago, completely out of the blue, I encountered Mariam Petrosyan on the street named after her great-grandfather, the great Armenian painter Martiros Saryan.

***

After graduating from Terlemezian Art College, Mariam Petrosyan worked in the animation department of Armenfilm studio. During that period, the studio worked on two cartoons based on William Saroyan's stories. Mariam recalls that it was the time subsequent to the golden period of the Armenfilm. However, Petrosyan dоes not consider herself as a cartoonist.

“I never wanted to be a writer. During my childhood, like all children of ballet dancers [Petrosyan’s parents are ballet dancers], I thought I would become a ballerina,” Petrosyan said “Then it turned out that my body is not arranged well; shoulders are too wide, legs are not suitable for ballet.” After realizing that dance was not in the cards, Petrosyan considered becoming a painter and drawing comics based on the characters of her stories. “See, I never thought about being a writer. I became a writer by the whim of fate. My first stories were strange. They look like the chapters of a big book, which has neither a beginning nor an end, and there was no plotline as well. While rewriting and editing a novel, I changed the language of the old texts a great deal,” she explained adding that when you modify the language, the content also changes.

Mariam Petrosyan exudes extreme modesty and sincerity. She almost glitters with some sort of inner energy similar to the atmosphere she has designed and created in her book; her soul seems to cope with the world from a periphery that does not fit into any hierarchy.

While “The Gray House” has been translated into 11 languages including Italian, French, Hungarian, Spanish, Polish, Czech, Lithuanian, and English, Mariam speaks incessantly, however, about the flaws of the novel and blushes when glowing reviews are given about the unconventional style of her narrative and sensibility and airiness of the language.

The chronicle of the writing and publication of Petrosyan’s cult saga is genuinely engrossing and full of adventure. The book was written over a period of 18 years, sometimes with long intervals, including a seven-year gap of no writing at all. She started to write her first stories in the late 80s when she was 18 years old. These stories served as a background for “The Gray House.”

In 1992 Petrosyan with her husband, Armenian graphic artist Artashes Stamboltsyan, moved to Moscow to work at Soyuzmultfilm studio. Petrosyan brought the unfinished draft of her book which she typed on a computer when she worked at a school in Yerevan. In Moscow, they lived in a dormitory (kommunalka) near the VDNKh amusement park (Vystavka Dostizheniy Narodnogo Khozyaytsva) for two years and came back to Yerevan in 1994.

Petrosyan recalls that one month before they flew back to Yerevan, they had no idea where they were going to stay. One of their friends recommended that they stay with Aunt Ella. “She was an absolutely extraordinary woman with a big heart. Everyone called her Aunt Ella. She allowed homeless dogs, cats, and people to live in her home,” Petrosyan said. “She was really an amazing woman who looks like a granny from Russian fairy tales with a round face and red cheeks. She worked as a cook at a boarding school for rich children. I gave her my book to read. She liked the novel very much, and she gave it to her son. After reading it, the son gave the book to his friend who just put my book in a locker for three years and took it out only when they were about to move.”

However, the epic journey of this book did not end there. After reading it, this boy passed the book to his parents, who passed it to their second son, who passed it to his girlfriend and it was thanks to her the book made its way to the publisher.

“The Gray House” was translated into English by Yuri Machkasov who did it of his own accord. “One of the young employees of LIVEBOOK Publishing [where the book was published in Russian] told me that a man from the United States has almost finished translating my book into English and wants to publish it,” says Petrosyan.

Yuri Machkasov was born in Moscow and studied theoretical physics. He moved to the United States in 1991. He lives in the Boston area and works as a software developer. Petrosyan says that Machkasov translates only those books that he is fond of. He translated one of Kurt Vonnegut’s books into Russian. He has also translated modern Russian poetry.

As for the Armenian translation of “The Gray House,” there have been several attempts to translate the book into Armenian. Mariam was shown four examples of experimental translations of her novel in 2011. “The language of the translations was overly literate,” explained Petrosyan adding that the voices of the characters sounded more like professors than children. “Our young people do not speak this language. On the other hand, if translated into a language spoken by our youth, it would be a disaster. It is very difficult to find a golden mean.”

Petrosyan's favorite character from “The Gray House” is Tabaqui who likes “being really loved and driving somewhere in the dark using a flashlight, and turning something into something completely different, gluing and attaching things to each other and then being amazed that it actually worked.”

“The Gray House” is probably one of the greatest novels you will ever read, and besides, the author is writing another one.

Mariam Petrosyan is writing!

Go to the souce of the images used in the graphic.

more on literature

A Room of Our Own: An Invitation to Write

By Atoussa S.

Atoussa S. explores the history of women writing and their absence in the literary canon. In this essay for EVN Report, she seeks answers to the questions: What circumstances make women writing/literature possible? What do women own in their writing? What is the meaning of this ownership?

An Agent of Undiscovered Literature

By Arevik Ashkharoyan

While contemporary Armenian writers are searching for a new language of expression, Arevik Ashkharoyan, a literary agent, has taken on the task of bringing their voices to a global audience. In this first essay for EVN Report, Ashkharoyan writes about the challenges of representing a book that many believe is about the army but in fact is a metaphor for a repressed society.

Thoughts on (not)Editing

By Tatiana Ryckman

In her piece on (not)editing Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s new novel “The Brick House,” author and editor Tatiana Ryckman says that Marcom's fiction changed her reading and writing life forever.

The Old Man on Avenida de Mayo

By Patrick Azadian

Patrick Azadian writes of unexpected human encounters and missed opportunities in this first work of fiction for EVN Report. The Old Man on Avenida de Mayo takes place in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Arto Vaun, Director of AUA's Center for Creative Writing and Editorial Board member of EVN Report, speaks with award-winning author Dawn MacKeen about the change-making force of telling our ancestor' s stories.