Sun Dec 01 2019 · 6 min read

When More is Less: Love and Cement in Revolutionary Yerevan

By Christopher Atamian

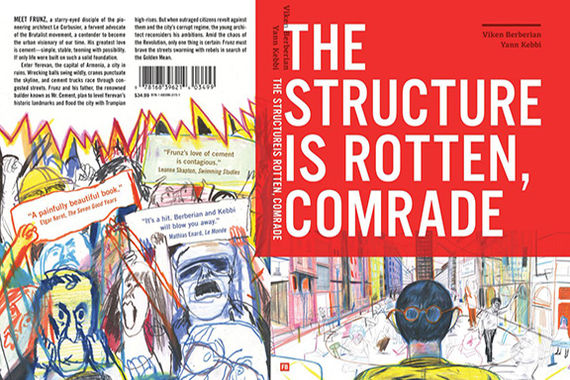

The Structure is Rotten, Comrade By Viken Berberian, Yann Kebbi

Fantagraphics Books, Seattle

That Viken Berberian seems to have hit his literary stride with a graphic novel is, upon reflection, not as surprising as one might think. In his two previous works “The Cyclist” and “Das Kapital: a Novel of Love and Money Markets,” the Lebanese-born author and L.A. repat relied on a keen sense of satire and storytelling to tackle socially relevant issues such as terrorism and corporate greed. Reading Berberian’s present opus brought to mind the fact that graphic novels lend themselves especially well to irony because they are by nature a satire of the real world as we know it. Given the paucity of good analytical novels about contemporary Armenian life, Berberian’s wry commentary is all the more welcome.

“The Structure is Rotten, Comrade,” takes the reader on a 318-page breakneck ride through the life, love and travails of young Frunz, an Armenian architect and Le Corbusier disciple, an adept of Brutalism and all things cement. (Having always had a perhaps surprising affinity for Brutalism myself, this reviewer empathized with the protagonist in question.) Frunz’s father Sergei (“Mr. Cement”) runs the real estate development company euphemistically known as RAD, tasked with rebuilding the center of Yerevan. ”Rebuilding,” a euphemism for the type of brutal gentrification that has destroyed city centers around the world. This will bring father and son into direct conflict with the capital’s citizenry when a more violent version of the real-life 2018 Velvet Revolution takes place.

Frunz’s first words as a child (“sea mint”) are a harbinger of things to come for the bespectacled nerd. After Frunz’s parents split up, he moves to Paris with his mother and as a teenager decides to rekindle his relationship with dad: “When I turned seventeen we started to Facetime on the last Sunday of every month. His head would occasionally pop into view to ask me if I’d had a croissant for breakfast and how my classes were going. He was absent a lot, not just in real time, but also on Facetime.” He returns to Yerevan and thus starts what Berberian cleverly refers to as “the unbearable lightness of falling in love with cement.” This Armenian son’s futile attempts to understand his father and to win his love lend great pathos to proceedings.

Situated after the fall of the Soviet Union, Berberian’s Yerevan--like the real-life capital--is in the middle of a building boom. A contemporary Tamanyan of sorts tasked with “beautifying” the Armenian capital, Sergei has let his unfettered capitalist instincts get the better of him. Others don’t quite see things his way, including an unnamed homeless man who has been kicked out of his apartment, or for that matter a whole crowd of angry revolutionaries who eventually storm RAD. When the good people of Yerevan complain about the price of rents and the destruction of landmark structures such as the Afrikyants Building, they are meant to be placated by the absurd fact that each new apartment will be equipped with three bathrooms. The evicted are given Alvar Aalto stools as door prizes. It’s small comfort to those made homeless while they await completion of their model units.

Berberian has always been a lover of metropolitan architecture, and his critique of current urban planning echoes far beyond Yerevan. In my native New York City, the garish new shopping mall masquerading as a neighborhood known as Hudson Yards turned a once gritty and affordable neighborhood on Manhattan’s far West Side into a gleaming facsimile of Miami (meh). Its design is so remarkably tasteless that I recently sprinted disgusted through the main building until I emerged breathless on the other side of Tenth Avenue.

At first Berberian’s wordplay in “Comrade” may seem overly coy, but as the book unfolds, he repeats tropes that bring even his flattest metaphors to vibrant life—it’s a neat trick. Take Less is More, the book’s bodacious female architecture student who dreams of becoming the next Kazuyo Sejima. The ambitious young woman at first resolves to do anything it takes to get a job at RAD, even if it means sleeping with Mr. Cement. After all, he’s a solid guy… But as she shimmies through the book ready to topple over due to her gargantuan mammalia, we realize that Less is More embodies a potent parody of corruption that runs through Armenia’s university system, a place where bribery and sexual shenanigans too often secure students top marks. This provides a good example of Berberian’s layering, which the reader can access on a number of different levels. Students of modernism, for example, will recognize in her name the famous adage that Mies van der Rohe coined, though the term was originally used by Robert Browning in his 1855 poem Andrea del Sarto (“Less is More, Lucrezia”). Another favorite trope: repetition. The omnipresent homeless man turned revolutionary repeatedly tells Frunz “May they bury you under three hundred tons of cement,” a wry take on the Soviet habit of addressing people in everyday life as if they were being toasted by a tamada.

“Comrade” is also a delight visually thanks to Yann Kebbi’s stylized color pencil drawings and muted tones. The French artist combines simple lines with a sophisticated understanding of storytelling. Some of my favorite details include a small graffito of The Little Prince stencilled on a city wall and wrecking balls flying through the sky ready to destroy the city’s most sacred monuments . At different points in the book, text disappears entirely and gives way to several pages of Kebbi’s fast-moving sketches. Forget text completely in order to read “Comrade” on another, entirely pictorial level and you still have a winner. Printed on rich, thick paper, the book brings back an old-style pleasure to the act of reading. How one “reads” a graphic novel is of course a fascinating mode of critical enquiry in and of itself.

In spite of the book’s often parodic tone, the most poignant moment comes towards the end of the story when Frunz’s father leaps to his death from his office window in order to avoid being executed at gunpoint. Frunz, recently returned from the French capital, rushes to his father’s side and exclaims simply: “Why did they kill my father?” Answer: “The revolution killed your father.” Story and visuals seamlessly combine here to produce explosive emotion. The revolution, like the ruthless gentrification that sparked it, has morphed into a many-headed hydra that no one can control. And while “Comrade” is above all allegorical, one senses strong autobiographical elements throughout its pages from an author who has experienced the violence of war first-hand in Lebanon.

“The Structure is Rotten, Comrade” is ultimately a critique of both corruption and capitalism, though the former Soviet figures alluded to fare no better. Few graphic novels have taken on so many issues with quite so much verve. Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis is one of course, but hers is a more didactic and overtly political message. Now less self-conscious and more confident than in the past, Berberian’s voice has matured. If he continues in this direction, he may soon cement his reputation as an important writer on the global literary scene.

also read

An Agent of Undiscovered Literature

By Arevik Ashkharoyan

While contemporary Armenian writers are searching for a new language of expression, Arevik Ashkharoyan, a literary agent, has taken on the task of bringing their voices to a global audience. In this first essay for EVN Report, Ashkharoyan writes about the challenges of representing a book that many believe is about the army but in fact is a metaphor for a repressed society.

Thoughts on (not)Editing

By Tatiana Ryckman

In her piece on (not)editing Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s new novel “The Brick House,” author and editor Tatiana Ryckman says that Marcom's fiction changed her reading and writing life forever.

The Eternal Magic of Mariam Petrosyan’s Gray House

By Lilit Margaryan

Translated into several languages, Mariam Petrosyan’s epic novel “The Gray House” has enchanted readers across the world. In this first book review, Lilit Margaryan speaks with the elusive Petrosyan about her life and the life of a novel that took 18 years to write.

We are pleased to open up a comments section. We look forward to hearing from you and wish to remind you to please follow our community guidelines:

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.