Prior to the 2018 Velvet Revolution, the Armenian public was generally considered pessimistic and skeptical about Armenia’s political process. In fact, the electorate's negative assessment of political parties and the electoral process was among the lowest in the region. This sentiment dramatically shifted with the ushering in of Nikol Pashinyan’s premiership. Large proportions of the electorate who were apathetic about the political process reassessed their outlook and reactivated their political participation. This was most evident during the 2018 election campaign season. Unfortunately, the voter re-engagement and jubilance would be short-lived, due to the 2020 Artsakh War and the current political crisis. Consequently, political efficacy has been replaced with a wave of voter alienation among a large percentage of the electorate. With snap parliamentary elections set for June 20, these issues of efficacy and voter alienation will be front and center.

Democratic regimes are defined by their ability to react to public opinion swings. Whereas authoritarian regimes can maintain a degree of insulation due to the presence of selectorates and thus survive with high voter apathy, democracies are maintained by the belief within the electorate of the ability to shape outcomes through the political process. Thus, democracies require political efficacy, or the belief that individuals can influence political outcomes. This political “buy-in” then shapes the arena in which voters and political parties interact. A democratic system consists of political parties whose platforms are closely aligned with their voter base as well as members of the electorate whose preferences lean toward the parties’ platforms. When party platforms are suddenly shifted or abandoned, the result is the alienation of a specific group of voters whose vote function is largely impacted by the now-marginalized issue. The persistence of voter alienation leads to voter apathy, a sense of indifference about the political system which naturally results in exodus by the electorate. Voter apathy, then, is what threatens the durability of a democracy. The fact that Armenia has recently positioned itself on a democratic trajectory makes avoiding voter alienation and voter apathy quite omnipotent. A recent poll by the International Republican Institute (IRI) provides a grim account of the Armenian electorate and one that should serve as a warning sign to all proponents of Armenia’s democratic transition.

In post-Soviet Armenia, the vicious cycle of partially free but completely unfair elections resulted in high levels of voter alienation. Voters lacked connections with parties based on issue convergence. Instead, election day voting behavior was due to the need to secure an election bribe or one’s place in a specific patronal network. This system of vote rigging and patronal voting dominated Armenian politics from the 1995 parliamentary election to the 2017 parliamentary election. In fact, throughout its post-Soviet tenure, Armenia has conducted only two elections that are internationally recognized as largely free and fair. The first was Armenia’s 1991 presidential election, where the process was mainly free and fair due to the nascent structure of Armenia’s patronal system. The second election to be categorized as largely free and fair was the 2018 parliamentary election, which witnessed the governing collapse of the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA), Armenia’s party of power, and the numerous patronal networks whose longevity depended on the RPA’s control of government.

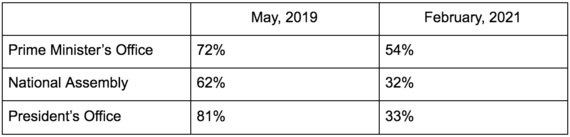

Armenia’s Velvet Revolution simultaneously brought a feeling of political efficacy and an overall trust in the country’s political system. This was evident in both pre-election surveys as well as periodical public opinion polls. For instance, an IRI poll conducted six months after the December 2018 election found that 44% of respondents disclosed a “favorable” perception of political parties and 72% of respondents disclosed a “favorable” perception of the Office of Prime Minister. The net positivity perception was also present for the National Assembly (62%) and the President’s Office (81%). Overall, public sentiment following the December 2018 election was largely positive due to an electoral rejuvenation on the part of the Armenian voter and a popular government whose central aim was to address the growing cancer in Armenian politics: patronalism.

The high hopes of the Armenian electorate was replaced by the reality of implementing political reforms without proper human capital and institutions. The process of judicial reforms through vetting stalled. The implementation of transitional justice failed to gain traction. The constitutional amendment process was halted due to exogenous factors. Overall, the Armenian voter quickly realized that eye-catching campaign rhetoric does not necessarily translate into fast-paced reformation. In addition, the Armenian voter became further disenfranchised with the events surrounding the 2020 Artsakh War, including the government’s information campaign about advancements, retreats and a supposed inevitable victory. The immediate fallout of the war and the current political crisis has brought back dissatisfaction about Armenian party politics. Not surprisingly, this phenomenon has rejuvenated voter alienation.

Evidence of voter alienation is found in IRI’s most recent poll. Overall, the study portrays an electorate that is largely exhausted by Armenia’s party politics but is willing to remain in the political arena, as exemplified in the large percentage of respondents (82%) indicating willingness to turn out for a future snap parliamentary election. Despite the surprisingly high turnout percentage, we witness across-the-board decreases in favorability ratings of Armenia’s executive and legislative branches. The values in Table 1 may lead many to conclude that the drop in favorability is least in the case of the Prime Minister’s Office and most in the case of the President’s Office. Unfortunately, we are unable to quantify the actual percentage drop because IRI’s May 2019 survey used a three-point favorability scale, whereas the February 2021 survey used a five-point favorability scale. Additionally, the percentages below are associated with favorability of each institution rather than the performance of the individual (or group of individuals) occupying each institution.

Table 1: Favorability Ratings for Armenia’s Executive and Legislative Branches (IRI)

Shifting our attention to measurements of voter alienation, we find evidence in the responses associated with the vote intention question. When asked for which party respondents would vote “if national parliamentary elections were held next Sunday,” a plurality of respondents (42%) answered “None.” Conventionally, Armenian voters are not as forthcoming with their vote intention as their Western counterparts. Instead, the Armenian electorate is more likely to select “Don’t know” or “Refused to answer.” However, in the IRI survey, just 14% of respondents disclosed either. In IRI’s May 2019 poll, only 10% of respondents disclosed a “Nobody” vote intention. The recent poll results demonstrate an exodus of standpatters from Armenian political parties, both among the My Step Alliance and opposition parties. The fact that almost half of the electorate does not disclose any party that will receive their vote is perhaps the clearest example of voter alienation.

Further evidence can be derived from a question measuring negative vote intention. When asked “For which political parties, if any, would you never vote?”, almost a quarter of respondents (24%) mentioned that they are “Against everyone else.” This provides additional evidence that the vote choice of the Armenian electorate is not tied to the current crop of political parties. What is driving this voter alienation in Armenian politics? Anecdotal evidence suggests the culprits are the government’s information (mis)management during the 2020 Artsakh War, the current political turmoil between the governing coalition and the anti-democratic opposition, and an overall dissatisfaction with politics. Evidence from IRI’s survey points more toward the political turmoil happening on the streets of Yerevan as the main culprit. Dividing the respondent sample size by residential location, we witness that 50% of Yerevan respondents disclosed a vote for “None.” Thus, the relatively high number of voter alienation in the entire sample is driven by the residents of the city which is the hotbed of political turmoil.

The current political crisis in Armenia has led to voter alienation. This has been primarily due to the events happening in Yerevan’s streets. By referencing Prime Minister Pashinyan through moral precepts, the 17-member bloc has “moralized” the Pashinyan premiership. That is, it has created an irreconcilable position around Pashinyan’s ability to remain prime minister. However, reconciliation is needed as it is likely to cease voter alienation and prevent voter apathy. The recent announcement of upcoming parliamentary elections taking place on June 20th is an important milestone in Armenia’s democratic trajectory. My Step’s 2018 mandate is no longer in existence, and a post-Artsakh war parliamentary makeup needs to reflect the seismic shift in public opinion. The June election will very likely provide the Armenian political elite of undeniable evidence of the magnitude of voter alienation.

In sum, Armenia’s current political leadership must be attentive to swings in voting behavior and prevent the path toward voter apathy as the presence of the latter is a threat to the sustainability of democracy in Armenia. The most tenable option moving forward is to collapse the narrow dichotomy Armenia’s political field finds itself in, as the Armenian voter finds one’s self stuck between two political forces that limit the public’s voting preference. The organic growth of new political forces, a “third way,” is becoming essential to offer the citizenry more voter preferences, and in the broader scheme of things, to break the stalemate of polarization, marginalization and voter alienation.

new on EVN Report

Electoral Reform Bill Made Public as Early Election Talks Continue

By Harout Manougian

Proposed changes to Armenia’s Electoral Code began in the summer of 2018. Almost three years later, the electoral reform bill has been sent to the Venice Commission for an expert opinion. Will the bill make its way into law before potential early elections, if at all?

Armenia’s Path to Getting Copyright Right

By Hovsep Markarian

Artists have been facing a real problem in Armenia: not getting fairly compensated for the music they release. In an age when sales of physical disk copies have drastically declined, with concerts and tours put on hold because of a pandemic, how are musicians supposed to get by?

Armenia in the Biden Era

By Artin DerSimonian

With Russia and now Turkey having new footholds in the South Caucasus following the 2020 Artsakh War, will Washington under the Biden administration attempt to counter these new developments?

Current Trends in Armenia’s Real Estate Market

By Suren Parsyan

Economist Suren Parsyan writes that due to the pandemic and the post-war situation, Armenia is witnessing a decline in purchasing power, a phenomenon that is having an impact on the real estate market.

Closing the Gender Gap

By Lara Techekirian

Although the principle of equal pay for equal work for men and women is fully implemented in Armenia’s Labor Code, a gender pay gap persists. Lara Techekirian looks at the challenges, the government’s response and presents a set of recommendations.

Comments

Vladimir Asriyan

3/21/2021, 7:45:49 PMDear authors, it would be great to translate this article to Armenian and circulate it, making it more accessible to the local population.