Tue Aug 20 2019 · 11 min read

Armenian Political Parties: Where Should the Money Come From?

By Harout Manougian

“Either politics controls money or money controls politics,” said Dr. Marcin Walecki, Head of OSCE/ODIHR’s Democratization Department, at a July 10 discussion with Armenia’s Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform. He was invited to address the group as it identified the regulation of political finance as a priority area of its ongoing electoral reform effort.

Armenia’s Current Political Finance Rules

Political finance in Armenia falls under two separate legal frameworks: campaign finance, covering election periods and regulated by the Electoral Code (the public disclosures of which get posted to www.elections.am) and political party finance, covering the ongoing operations of political parties and regulated by a separate Law on Political Parties. Parties are also required by Article 46 of the Constitution to publish an annual financial report, which gets posted to www.azdarar.am.

Campaign finance is only relevant to a very short campaign period. For the Dec. 9, 2018, election, the official campaign period covered only two weeks. Each party or alliance contesting the election is required to set up a separate campaign account to cover their advertising and rally costs for this period, but many other costs, such as salaries, consultant fees, campaign offices and transport, are specifically excluded. For parliamentary elections, Articles 26 and 92 of the Electoral Code allow only the following sources to contribute to the campaign account:

-

The political party itself: up to 100,000,000 AMD (~$210,000)

-

Candidates running for the party: up to 5,000,000 AMD (~$10,000)

-

Individuals with the right to vote: up to 500,000 AMD (~$1000)

The total spending cap (from their campaign account, which, again, excludes campaign offices and other significant expenses) during a parliamentary election for one party or alliance is 500,000,000 AMD (~$1,000,000). As the party itself can only pitch in one fifth of that amount, it would need to mobilize a very effective two-week fundraising effort if it hoped to hit that cap.

Corporations cannot contribute directly to a campaign account; though two did try in 2018. ArmHydroEnergyProject CJSC and R. G. Construction Ltd made donations of 700,000 AMD and 60,000 AMD respectively to the My Step Alliance. The amounts were inadmissible and transferred to the state budget by the Oversight and Audit Service (OAS) of the Central Election Commission (CEC).

Corporations can, however, donate to a political party, which can then transfer the amount, within the 100 million AMD limit, into its campaign account. Annual donation limits to political parties, spelled out in Article 24 of the Law on Political Parties, are as follows:

-

Commercial corporations: up to 10,000,000 AMD (~$21,000)

-

Non-commercial corporations: up to 1,000,000 AMD (~$2,100)

-

Individuals: up to 10,000,000 AMD (~$21,000)

Transparency International’s Yerevan Office, at a June 25, 2019, public forum event, recommended banning corporate donations altogether.

Did They Really Mean That?

Article 24 of the Law on Political Parties goes on to prohibit donations from, among others, foreign corporations and “citizens of foreign countries.” That wording is problematic as it implies Armenian dual citizens cannot donate directly to an Armenian political party, as the descriptor “citizen of a foreign country” technically includes them. The common understanding of the law’s intention, however, is that any Armenian citizen is eligible to donate to Armenian political parties.

Another quirk is that membership fees are considered to be separate from “donations.” Article 23 sets a maximum annual membership fee of 1,000,000 AMD (~$2,100). While Article 12, s. 2 reads:

“Capable citizens of the Republic of Armenia who have attained the age of 18 may be members of a political party.”

However, that section leaves out the crucial word “only.” It does not say outright that individuals who are not citizens of Armenia, or have not yet turned 18, cannot join an Armenian political party. In fact, Article 13 enumerates people who may not join a political party – judges, prosecutors, investigators, the President, the Ombudsman, and members of the CEC, Television and Radio Commission, Audit Chamber, or Central Bank – but does not include non-citizens of Armenia, even though the common understanding of the law’s intention is that non-citizens may not join Armenian political parties and may not pay them membership fees or donations.

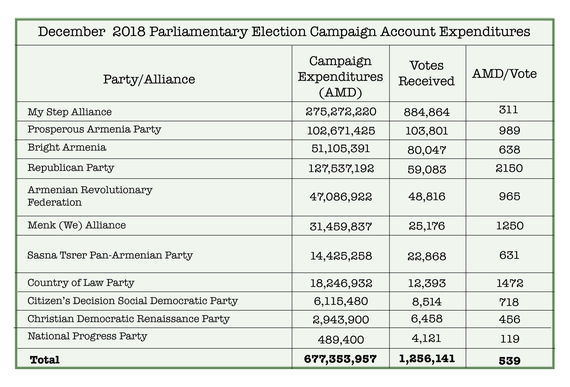

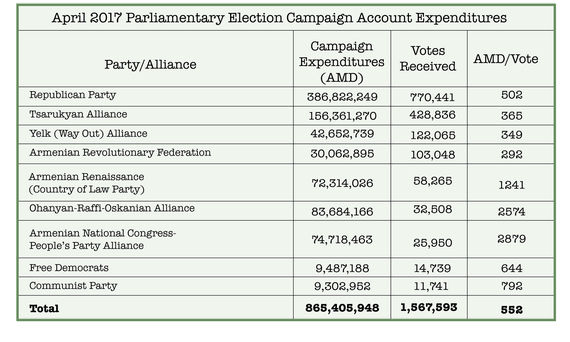

Campaign Finance in Armenia’s Parliamentary Elections

A general principle in election campaigns is that the side that spends the most money will usually win. Conversely, the side expected to win usually attracts the most donations. That principle held up for both the December 2018 and April 2017 parliamentary elections in Armenia, as shown in the tables below.

Keep in mind, however, that those figures include mostly advertising and rally costs. Crucially, the OSCE reported credible allegations of vote-buying in the April 2017 election, the sums for which are likely not reflected in official expenditure disclosures; whereas in their report on the 2018 election, the OSCE reported a general absence of vote-buying, electoral malfeasance, and pressure on voters.

The reported figures also leave out campaign office space. The Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) owns or rents space in 51 different buildings, according to its declaration of assets and income for the 2018 election. In contrast, the Civil Contract Party, the core of the My Step Alliance, declared only one rented office in central Yerevan. While other parties did include rented properties in their pre-election disclosures, the Prosperous Armenia Party declared zero real estate holdings, even though another document it had filed outlined $57,000 in office rent costs for roughly the same time period.

Although donations to parties from state budgets are prohibited, the Republican Party’s declaration also showed that it received $400 for renting out its surplus property to the Vayots Dzor regional governor’s office (marzpetaran) – rent payments would not be considered donations, but it is fundamentally inappropriate for a state agency to be leasing real estate from a political party. The only other party that, in their pre-election filing, declared income from their real estate holdings was the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), which received $1750 in rent payments from Inecobank. The ARF declared real estate assets in 45 different buildings, giving them the second-widest coverage of campaign office locations.

The National Progress Party, which ultimately came in eleventh place, was registered on November 13, 2018. In the twelve days from its founding to November 24, it declared zero income but also showed that it had accumulated 2,000,000 AMD (about $4200) in cash.

Not only do political parties need to declare their assets and income, but so does every single one of their candidates. Ever wonder how rich Gagik Tsarukyan is? You can visit the www.elections.am website, expand the correct menu under the page for the last parliamentary election, download Prosperous Armenia’s candidates’ .rar file, extract it using a program such as WinRAR or 7Zip, open the first folder called “1.G.TS.”, and re-order the seven scanned .jpg files to find out he owns:

-

11 properties

-

13 cars, of which two are Rolls Royce Phantoms and one is a Bentley

-

6 gold watches, collectively worth $1.8 million U.S.

-

3 gold rings, collectively worth $4.7 million U.S.

-

Almost $200 million in cash assets

-

Shares in 45 different corporate entities

In contrast, Nikol Pashinyan declared $1800 in cash and a 2012 Hyundai Sonata.

Public Funding of Political Parties

Although donations to Armenian political parties are not tax-deductible, the Law on Political Parties does include provisions for direct and indirect funding by the state.

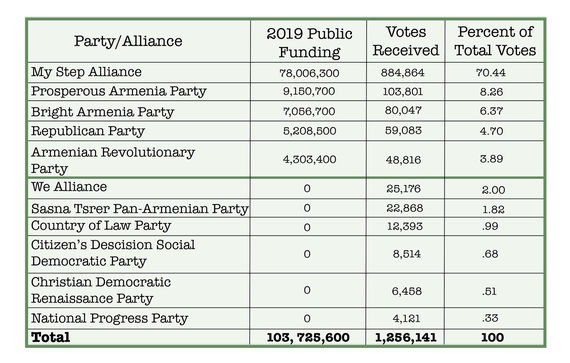

Introduced in 2002, Article 26 states that parties that receive at least 3 percent of the votes in a parliamentary election are entitled to direct funding from the state budget in proportion to their vote share. The total amount budgeted toward this support cannot be less than 40 AMD multiplied by the total number of potential electors in the last election, whether they voted or not (2,593,140 electors in 2018). The 2019 budget allocated this minimum amount as follows:

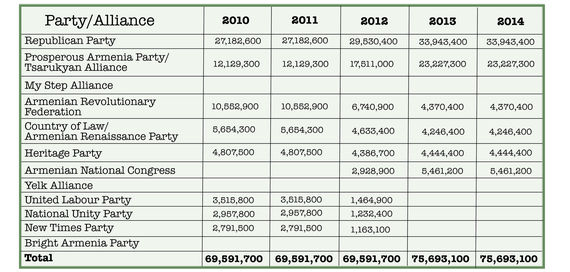

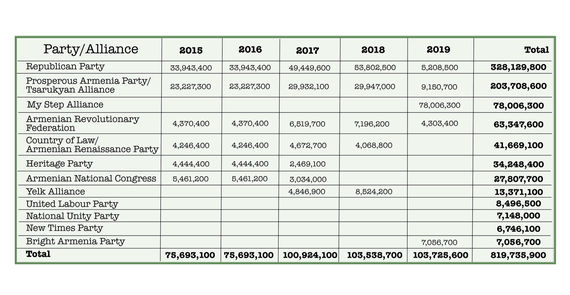

One will notice that the threshold for receiving public funding (3 percent) is lower than the threshold to receive seats in parliament (5 percent) such that, under the current formula, the RPA and ARF will continue to collect some assistance from the state budget even if they have no elected MPs. The table below outlines all the parties that have received public financing over the last ten years.

Of course, public funding does not need to be directly proportional to vote counts. The current formula favours incumbent parties that are already dominant. Another possible approach is to provide every party that surpasses a given threshold with the same flat amount, enough to cover minimal operational expenses. Alternatively, a regressive formula could be used that gives less funding per vote to the largest parties – but still a higher overall sum.

Not all public financing of political parties is in the form of direct cash payments, however. All parties fielding candidates in an election are eligible for indirect support in the form of free airtime on television, free ad space on billboards, and free access to public space to hold rallies.

At the July 10 meeting between OSCE/ODIHR and Armenia’s Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform mentioned at the beginning of this article, Dr. Marcin Walecki suggested that Armenia’s current level of public funding for political parties needed to be increased. He acknowledged that allocating tax dollars to parties is a hard political sell but he likened money in politics to a glass of drinking water. First, it should be transparent; anyone should be able to see what’s in the glass. Second, half the glass should come from a dependable source, i.e. the state budget, so that no one gets desperate due to thirst. Third, a regulator needs to actively guarantee quality control, ensuring that the water is clean. And, finally, you should not overfill the glass.

Tax-Deductible Donations

Contrary to many other democracies, donations made to political parties in Armenia are not currently tax-deductible. Instead of straight, budget-to-party funding, the government can provide a tax deduction to citizens that make a donation to a political party. Proponents of this approach argue that it keeps politicians accountable to those they represent by forcing them to reach out and actively make a pitch that attracts voluntary contributions, instead of falling out-of-touch in an ivory tower in the capital.

In Canada, an individual that makes a $400 (CAD) donation to a federal political party will receive $300 (75 percent) back on their tax return. Whether this approach is well-suited for Armenia remains to be seen. Salaried workers do not currently need to file annual tax returns. Even cash-based sole proprietors, like taxi drivers and fruit-sellers, who should be filing tax forms, rarely do so and are rarely pursued. Implementing the system would therefore require building out a new expensive level of administration to process the requests. On the other hand, a similar tax refund scheme for purchasing newly-built apartments has proven very popular, rewarding workers in the formal economy.

A similar approach with less administrative burden involves paying the state’s contribution directly to the political party. Sometimes referred to as a “matching” or “bonus” system, the state would top up every donation that a party receives. That is, if a voter donated 1000 AMD to XYZ Party, the state would contribute an additional 1000 AMD (or 200 AMD, or 2000 AMD, or any other predetermined percentage written into law) to the party as well. One weakness of this model is that it can make vote-buying schemes - a problem that has plagued Armenia in the past - profitable for political parties that also want to launder dark money. Given a 1:1 matching system, a party representative could give a voter 15,000 AMD in cash and ask them to make a 10,000 AMD donation to the party, to which the state would match an additional 10,000 AMD. Both the voter and the party would be ahead by 5000 AMD each, at the taxpayer’s expense, and the original 15,000 AMD from a likely impermissible origin would be successfully deposited in the party’s account.

While the same scheme is technically possible if the state reimburses the donor (the tax-deductible model) instead of paying the bonus to the party directly, that slight difference involves the donor being out-of-pocket in the short term until the tax deduction paperwork is complete, which is a harder sell for a shady character looking for accomplices.

Need for Effective Oversight

Drawing from the OSCE/ODIHR election monitoring report on the 2018 parliamentary election, the Yerevan office of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) made a number of recommendations surrounding the Oversight and Audit Service (OAS) of the Central Election Commission (CEC). The OAS has a staff of three people. During the 2018 election, they were joined by four additional auditors seconded by political parties, looking out for their specific party’s interest. IFES recommends expanding its organizational capacity and legal jurisdiction in order to carry out its mandate more effectively.

Third Party Advertising

Armenia is not the only country grappling with the implications of money in politics. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission was a landmark 2010 supreme court case in the United States, which opened the door for corporations to spend unlimited amounts of money on election-related messaging and advertising. Previous restrictions were struck down as violations of corporations’ freedom of speech. A parallel case in Canada, Harper v. Canada (Attorney General), came to the exact opposite conclusion in 2004: The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that excessive expenditures on political messaging would “bury” the speech of others, and upheld spending caps as a way to maintain “a level playing field.”

Both those cases were related to third-party advertising, not expenditures by the political parties themselves. The prevalence of election spending by entities other than those fielding candidates arose as a way to circumvent limitations on political financing such as spending caps, donation caps, and mandatory disclosure. That lesson is important to keep in mind as the Armenian Parliament targets political finance as the first step in its electoral reform legislative package.

Arm’s-length organizations, affiliated with political parties but organizationally distinct, are already gaining prevalence in Armenia. Some parties have a separate election monitoring organization that allows them to place additional bodies in a polling location. The Gagik Tsarukyan Charity Foundation has been accused of aligning its charitable projects with the political interests of its founder’s Prosperous Armenia Party. The Civil Contract Party chose to stand for election in 2018 under the “My Step” banner, echoing the movement Pashinyan started with his march from Gyumri to Yerevan earlier that year, after which a charity started by Nikol Pashinyan’s wife is also named.

Then, there are producers of political merchandising, which may not be affiliated with a party at all but are pursuing a profit motive. Examples at Yerevan’s Vernissage market include the black “dukhov” baseball cap or wood carvings of the ARF coat of arms. Enforcing copyright on recognizable political symbols could both ensure that parties get a share of these revenues and that they show up in public financial filings.

In the Internet age, however, the hardest third parties to tackle are those beyond the country’s borders. Facebook and Google could significantly impact an election by suppressing the content of one party and promoting another, if they chose to do so. As American companies, they are subject to American laws but, without a physical presence in Armenia, they could decide not to engage with Armenian regulators at all. (Note that this is a hypothetical scenario. Armenia does not have a fairness doctrine in place for online or print media anyway.) The companies don’t even need to be actively involved. Foreigners could spend millions on Facebook ads, targeting Armenian voters, without ever entering the jurisdiction of Armenian governmental regulators. The mental exercise suggests that ideas on how to address media concentration may need to be added to the political financing discussion.

Extensive study will be required as part of a thorough review of political finance in Armenia. Fortunately, with high profile municipal elections scheduled for Gyumri and Vanadzor in 2021, new regulations resulting from the process will get an important test run ahead of the next parliamentary election in 2023.

Harout Manougian is a volunteer legislative assistant to MP Hamazasp Danielyan, who heads the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform. Opinions expressed are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of MP Danielyan or the working group.

related

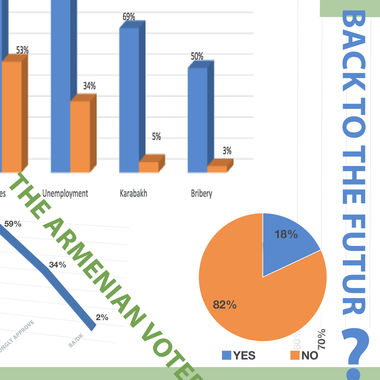

Back to the Future? The 2018 Parliamentary Elections and the Armenian Voter

By Rafael Oganesyan

The director of the Armenian Election Study, Rafael Oganesyan takes a critical look at the recent snap parliamentary elections that took place in Armenia and utilizing fresh data explores the transformation of the Armenian voter.

Women Continue to Sit on the Sidelines in Armenian Politics

By Gohar Abrahamyan

Despite the fact that more than 50 percent of Armenia’s population are women, only one party has entrusted the number one slot on its electoral list to a woman. Gohar Abrahamyan takes a look at which forces have the most women on their lists and why women’s presence alongside men is not the result of good will and remains problematic.

Armenia and Artsakh: A Tale of Two Electoral Reforms

By Harout Manougian

Electoral Code reform has been on the agenda in Armenia following the Velvet Revolution last year and the Republic of Artsakh just enacted amendments to its Electoral Code as it prepares for national elections in 2020. Harout Manougian looks at the situation in both republics.