Mon Aug 24 2020 · 10 min read

Armenia’s Entire Voter List is Available Online: Here’s What It Shows

By Harout Manougian

Access to the signed voter lists after an election, which indicate who showed up to vote, has been a long-standing political issue in Armenia. During the Serzh Sargsyan administration, civil society groups such as the Transparency International Anticorruption Center (TIAC), the affiliate of Transparency International in Armenia, were concerned about the large number of Armenian citizens who remain on the voter list despite having moved abroad years ago. Many speculated that electoral fraud may be taking place through the form of party operatives voting under the names of citizens they knew were not in the country and would not show up themselves.

To address this concern, after the 2015 Constitution was passed, the Electoral Code was updated to provide for the scanning of the signed voter lists and uploading them to the Internet for public scrutiny. Thus, an Armenian citizen who was abroad could check to see if anyone had signed by their name and voted on their behalf. (Armenia has not allowed out-of-country voting for regular citizens since 2005.)

At the time, the Venice Commission, which provides expert opinions on electoral legislation, expressed concern about the implications of the new procedure on voters’ personal data. While they supported providing access to the voter lists to election observers, they quoted their Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters, which states that “since abstention may indicate a political choice, lists of persons voting should not be published.”

Ultimately, however, the provision was kept in order to maintain confidence in election results. Davit Harutyunyan, an MP at the time with the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA) and a former Minister of Justice, who played a leading role in drafting the 2016 Electoral Code, stated that publishing the lists did not contradict Armenia’s Constitution, which includes a section on the protection of personal data (Article 34). The civil society groups advocating for the change were satisfied; while they deplored the vote bribery that took place in the ensuing 2017 parliamentary election, the new procedure was successful in allaying fears of widespread voter impersonation.

For this reason, after the 2017 and 2018 parliamentary elections, the signed voter lists from 2,000 precincts are scanned as pdf files and made available on the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) website. They include the full name, address and date of birth of every citizen over 18 years old. If they voted, it will also include their signature, and sometimes their national ID card number.

In other countries, hackers need to put a lot of work into gaining access to this type of bulk personal data. Such an incident occurred in March 2020, when a file containing information about 5 million Georgians was discovered by a data breach monitoring and prevention service. Although initial reports stated that the data originated from the Georgian CEC, there would have to be additional sources as well, since the file included phone numbers, which the Georgian CEC does not collect.

In Armenia, this data is posted online freely and anyone in the world can download it in the days following a national election. Converting the signed voter lists into a searchable database is no simple task, however. The files would have to be subjected to an Optical Character Recognition (OCR) process to convert the scanned images in the pdf file into searchable text, which takes time and money that not everyone has.

For the hopelessly curious, there is a simpler route, however. The Armenian CEC website also includes a Voter Registry Search feature, which has been highlighted in a previous EVN Report article. It does require you to enter a search term in both the first name and last name fields. The results will bring up all voters whose first name and last name begin with those search terms. Thus, if you really wanted to, you could enter the 1521 (39 x 39) combinations of the 39 letters of the Armenian alphabet and then program a text scraper to compile all the results into your own database.

But, you don’t even have to go through that. Before a national electoral event, the Armenian Police, who are responsible for maintaining the national resident registry on which the voter list is based, publishes (easily searchable) Microsoft Excel files containing the entire voter list, ostensibly for citizens to check for inaccuracies. Though this list does not include voting history, it is comprehensive data on every Armenian citizen over 18 years old, who is recorded as resident in the country. Although the National Assembly voted on May 30, 2020 to officially cancel the constitutional referendum (originally scheduled for April 5), this list was still available on the Armenian Police website at the time of publication. It is time-stamped as having been uploaded on February 25, 2020, meaning that it has been freely accessible on a government website for half a year.

On August 17, 2020, as part of their online public consultation series, the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform held a session to discuss the voter lists. It was an opportunity for stakeholders to share ideas and express their opinions. One proposal was to remove the Microsoft Excel version of the full database (on which the data analysis performed later in this article was performed) from the police.am website and provide it only to organizations involved in the election process, such as observer missions and political parties.After analyzing the comprehensive dataset, here are some major takeaways.

Overall Totals: Largest Regions and Cities

The list includes a total of 2,585,034 voters, who would all be Armenian citizens, have a local Armenian address and be at least 18 years old. Armenia’s 10 regions and the Yerevan Capital Region rank as follows:

Yerevan: 855,314

Kotayk: 241,580

Lori: 236,694

Armavir: 235,316

Shirak: 229,105

Ararat: 222,819

Gegharkunik: 188,039

Aragatsotn: 117,467

Tavush: 107,167

Syunik: 105,440

Vayots Dzor: 46,093

There are a total of 501 municipalities listed; though, there is an ongoing effort to amalgamate smaller communities. Six of them have less than 100 citizen-residents over 18. The 20 largest municipalities are:

Yerevan: 855,314

Gyumri, Shirak: 123,779

Vanadzor, Lori: 96,222

Vagharshapat, Armavir: 46,030 (formerly Etchmiadzin)

Abovyan, Kotayk: 44,987

Hrazdan, Kotayk: 44,327

Kapan, Syunik: 34,818

Charentsavan, Kotayk: 30,071

Armavir, Armavir: 29,213

Berd, Tavush: 25,028

Sisian, Syunik: 23,104

Gavar, Gegharkunik: 22,929

Goris, Syunik: 22,339

Artashat, Ararat: 21,735

Dilijan, Tavush: 20,389

Sevan, Gegharkunik: 19,849

Yeghvard, Kotayk: 19,602

Ashtarak, Aragatsotn: 19,448

Alaverdi, Lori: 19,242

Aparan, Aragatsotn: 18,004

Passports are the Primary ID Document

It is widely known that the voter list contains inaccuracies. When an Armenian citizen moves abroad, they likely will not go through the trouble of deregistering their residence. Although those who die in Armenia are regularly removed from the list, if an Armenian citizen dies abroad, the local authorities may never find out about it. Under current processes, their name would remain on the voter list forever.

To address this issue, during the previously-mentioned public consultation session, Daniel Ioannisyan of the Union of Informed Citizens (UIC) proposed removing all the names from the voter list that have not had a valid (i.e. unexpired) passport for more than six months. He estimates that this will result in 188,000 names being removed from the list, about 7% of the total.

The current artificially inflated voter list injects inaccuracies into officially-reported voter turnout figures. These figures have legal consequences in that referendums in particular need to meet a minimum turnout to be valid, which is calculated off the total number on the voter list. In addition, after recent amendments to the Electoral Code, municipalities will use a different electoral system depending on whether they have more or less than 4000 voters.

In other countries, a sizable portion of the population may not have a valid passport at any given time. In Armenia, however, a passport is used as the primary national identification document. A separate ID card can also be ordered but it references the person’s currently-valid passport number. A valid passport (or its ID card alternate) is necessary to participate in the economy by entering into an employment contract, making a transaction at a bank, receiving pension payments or getting a phone number. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was a requirement to carry either a passport or the ID card with you just to go outside. As there may still be some residents with an expired document, it was recognized that the change should be accompanied by a publicity campaign to encourage residents to renew their expired passport. The cost to do so is 10,000 AMD ($20) and the new passport would be ready in three working days, with a validity period of ten years. The fee is much higher if one’s existing passport has been lost, however.

Even if they do not have an unexpired ID, do not reside in Armenia and are not on the voter list, any Armenian citizen can still vote on Election Day by presenting proof of citizenship to a police station to obtain a slip they can use at the polling station (they would still have to be in the country on Election Day).

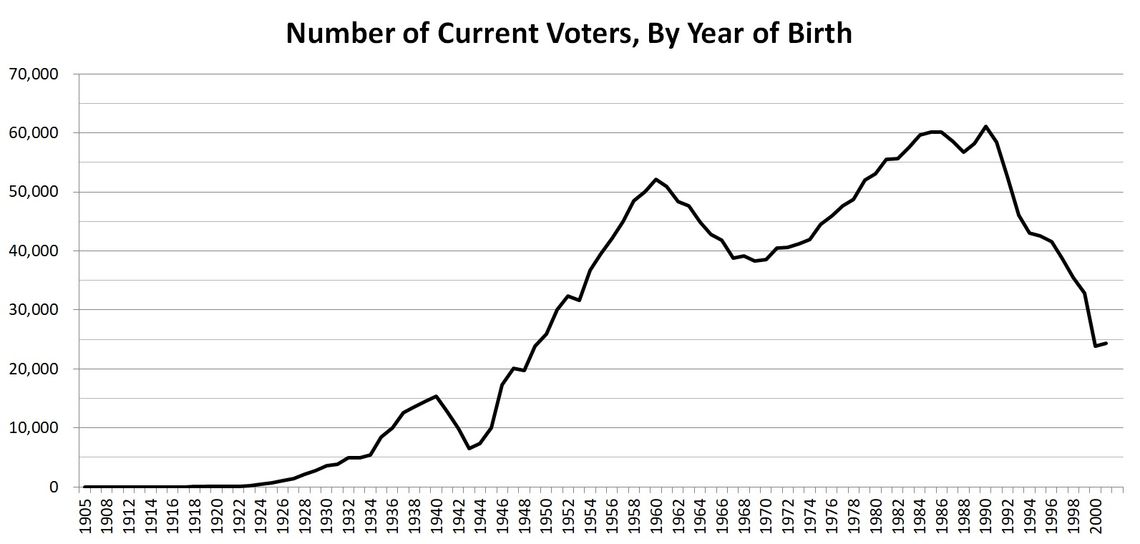

Armenia Supposedly Has 172 Centenarians

According to the voter list, there are 172 voters who will reach the age of 100 by the end of 2020. The exact number at the time of publication is difficult to ascertain as the month and day a person is born is not always known. Almost 23,000 voters have “00” entered under their month and day of birth, with only a year available.

The oldest person on the voter list is a woman from the Vayots Dzor region who was born on May 5, 1905. If she is indeed still alive, she would be tied for the sixth oldest living person in the world. The voter list includes 23 people who were born in 1915 or earlier. They all have female names.

Graphing the frequency for each year of birth shows three noticeable dips. The first is from 1941-1945, when many men were fighting in the Soviet Red Army and were not at home to help conceive babies. The second occurs in the 1960s and early 1970s; the males in this demographic would have been in their prime fighting years during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict of 1988-1994. The third, smallest dip occurs from 1987-1989, after which there is a steep drop-off in the 1990s, after independence.

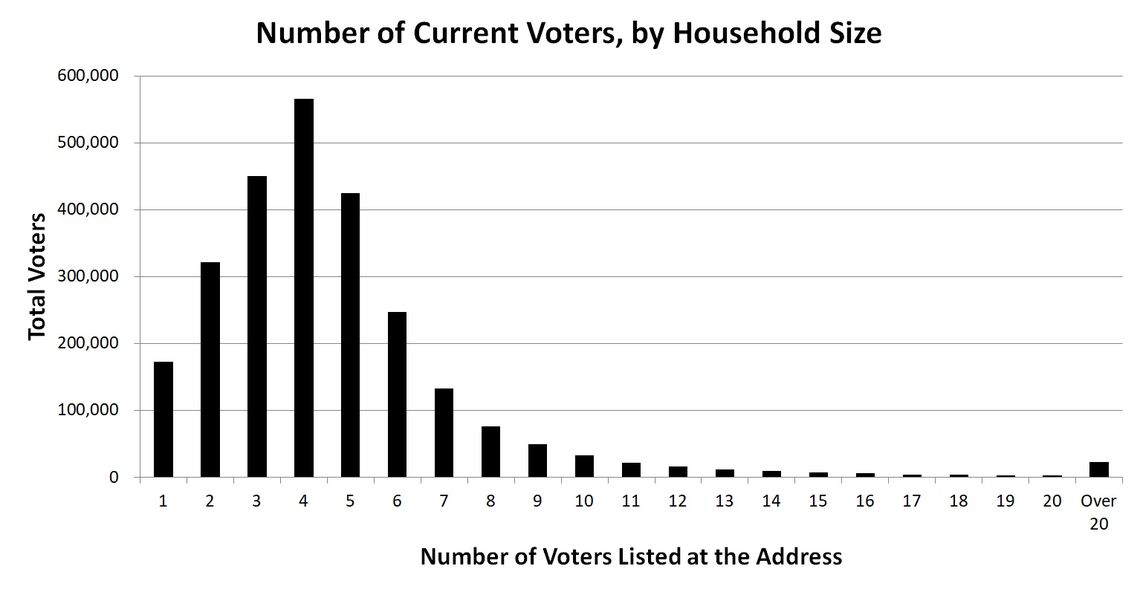

Addresses Are Not Exact

For the most part, addresses listed on the voter list include a street name, building number and usually also an apartment number. Not all addresses are so exact, however. The most common feature is for the apartment number to be left out such that all the residents in a large building are listed at the same address. The result is that some addresses show that hundreds of people live there. Likewise, sometimes only a street name or even just the neighborhood is given. For example, the address with the largest number of registered voters (at 392) is the Hatsarat neighborhood of Gavar, Gegharkunik. Something weird seems to be going on in Yerevan’s Arabkir district, however, where 234 voters have their address registered as “Kanaker Tunnel,” the second-highest total in the country. 549 have no street address at all, listing only the municipality. 4.4% of all voters were listed at an address with more than 10 voters.

It was most common for a voter to be registered at an address with a total of four voters; such households made up 22% of the entire list. 75% of all voters were registered at an address that had five or less voters. Note that the voter list includes a citizen’s registered address, which may not be where they normally live. For example, a young person may have moved to Yerevan from a smaller community but maintained their official registered address at their parents’ home. When this is the case, they are expected to return to their registered address to cast their ballot.

There are also suspicions that some voters may be registered at more than one address. There are 104 pairs of people who have the exact same first name, last name, patronymic (father’s name) and date of birth (including day and year), though their addresses are different. It is possible that they are mere coincidences and actually represent 208 unique individuals, but it’s also possible that they are duplicate entries, registering the same person at two different addresses. A comparison of their signatures from the signed voter lists could not be completed before the publication of this article.

The Most Common Armenian Names

It is often pointed out that President Armen Sarkissian has the quintessential Armenian name, similar to John Smith in English. While it turns out that Armen is empirically the most common Armenian boy’s name, according to the voter list, Sarkissian (more commonly transliterated as Sargsyan) turns out to be only the third-most-common last name. The top twenty rankings are shown below:

A full 24% (almost one in four) of those on the voter list have a first name that starts with the letter “A” [Ա]. The least common letter to start a first name is [Ը], which makes the schwa sound. Only 17 voters in the whole country have a first name that starts with that letter; four of them are named Entruhi, which literally means “voter” or “selector” in its feminine form.

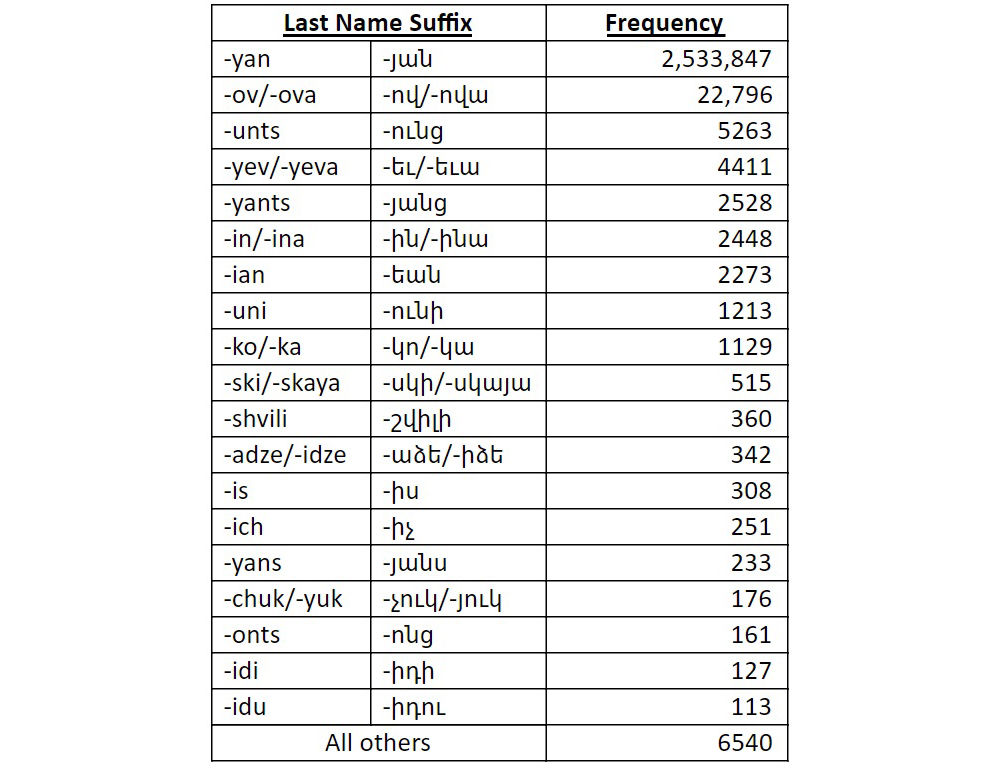

One feature that is ubiquitous is the “–yan” last name suffix that immediately identifies an Armenian. Among the 2,585,034 names on the voter list, 2,533,847 (98%) end in –yan (–յան). This spelling, in Armenian, conforms to the reformed spelling rules used in the Soviet Union. Only 2,273 voters use the pre-Soviet –եան spelling, which is common in the diaspora. Other Armenian last name suffixes include –unts, –yants and –uni. The most common suffixes are shown below; they include Russian/Slavic, Georgian and Greek constructions.

In terms of prefixes, an Armenian family might have had “Ter-” (or “Der-” using Western Armenian pronunciation) added to the beginning of their last name if (at some point in the past) the head of the household was a married priest in the Armenian Apostolic Church. The prefix turned out to not be that common in Armenia, where only 4093 people on the voter list bear it; though, that sum does not include those with the last name Terteryan/Derderian, which number 1783 by themselves. As a side note, some Dutch last names also begin with the “ter” prefix.

also read

Logging Your Internet Activity: What's True and What's Not

By Harout Manougian

A draft document penned by an independent government regulator has raised important questions about digital privacy. Though the proposal definitely has issues, the rumors it sparked are alarmist and exaggerated.

A Country Where the Word Privacy Does Not Exist

By Samvel Martirosyan

Is Armenian society concerned about privacy or the protection of personal data? Samvel Martirosyan is doubtful.

Two Different Approaches to Data Retention: What Can Armenia Learn?

By Kristine Hovhannisyan

This article dives into the international experience in the field of data retention policy to help inform the decision-making process in Armenia.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.