Thu Feb 27 2020 · 9 min read

Two Different Approaches to Data Retention: What Can Armenia Learn?

By Kristine Hovhannisyan

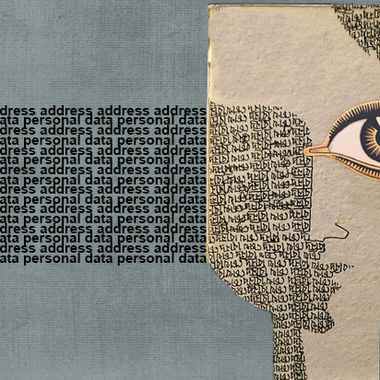

In October 2019, a draft proposal by Armenia’s Public Services Regulatory Commission (PSRC) was made public that called for Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to retain data about their customers, including details about their email communications. The proposal met a poor reception, with some advocates expressing concerns about privacy implications. To date, there has been no progress on the draft; it has not yet been amended nor is it any closer to being adopted.

This article dives into the international experience in the field of data retention policy to help inform the decision-making process if and when it is restarted. It presents the arguments and justifications for abolishing data retention under the EU law. It provides an analysis of the judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union (the Court, or CJEU) for invalidating Data Retention Directive 2006/24/EC (the Directive).

As a contrasting example, the Australian data retention legal framework is added to this analysis. This research work happened to coincide with a trip to South Australia in January 2020. Conversations took place with Dr. Matthew Sorell and other leading experts in the field of telecommunications, cyber security, law enforcement, case law and academia to understand the justifications and the drivers behind the data retention legal regime in Australia.

The term data retention, when referring to both the EU Directive and the Australian legal framework, should be understood as storing metadata for the purpose of making it available to relevant national authorities. Metadata is data about other data. As an analogy, think of an envelope that contains a letter. The metadata would be the name and address of both the sender and the recipient given on the envelope, but not the content itself, which in this case is the letter in the envelope.

The ‘Blanket’

In two different cases, the Court has confirmed that the EU Directive constitutes interference into a person's private life. The legality of the Directive was challenged for the first time in the joint case of the Digital Rights Ireland Ltd (C-293/12) and Kärntner Landesregierung (C-594/12) in 2014, when the Court invalidated the Directive. The second time, in 2016, there was another joint case of the Tele2 Sverige AB (C-203/15) and Watson (C-698/15), where the Court reaffirmed its position.

One could ask why there was a need to reaffirm a second time. In brief, it happened due to the fact that, after the 2014 judgement, the Swedish Tele2 telecom company stopped retaining data. The Swedish Post and Telecommunications Authority (PTS) ordered Tele2 to resume the retention. Consequently, this order was taken to the Administrative Court in Stockholm, the Administrative Court of Appeal and eventually ended up again at the CJEU.

In 2014, essentially, the Court examined the validity of the Directive with regards to two articles of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union: a) Article 7, Respect for private and family life and b) Article 8, Protection of personal data. The argumentation given in the Court’s judgment for invalidating the Directive are the following:

-

The Directive targets all traffic data (fixed telephony, mobile telephony, Internet access, Internet e-mail and Internet telephony), covering all possible means of communication. This dataset could be used to define the personal habits of an individual and therefore constitutes an invasion to privacy;

-

The Directive covers both the subscribers and the users. This means that it applies in a generalized way, without any criterion for distinction;

-

The Directive does not limit or provide exceptions to preclude communication of a person that is subject to professional secrecy;

-

The Directive does not scope in any way the data to be retained for a specific time, geographical area and/or circle of persons that are likely to have been engaged in serious crime;

-

The Directive does not provide an objective criterion for defining the threshold of what constitutes serious crime, which is left up to domestic legislation of the member states to define;

-

The Directive does not stipulate procedural conditions for accessing the data and further usage by the competent national authorities, and it does not limit the access to data for the purpose of preventing and detecting clearly defined serious offences or for prosecution thereof;

-

The directive does not state any requirement for advance review by a court or an independent administrative body to establish or ascertain the need for such a request (access to retained data). Moreover, the Directive does not put any obligation on member states to establish an oversight mechanism;

-

The Directive does not separate or make any differentiation of categories of data to be retained for a minimum of six months;

-

The Directive does not state an objective criterion on how the determination of the time within the given range (minimum 6 months and maximum 24 months) should take place;

-

The Directive does not state specific rules that are for the purpose of safeguarding (a) extensive amount of stored data and (b) of sensitive nature, (c) protect against the risk of unlawful access, and there was no obligation put on member states under the Directive to define these types of safeguards.

-

The Directive does not ensure irreversible destruction of retained data at the end of the data retention period;

-

The Directive does not create an obligation to retain data within the European Union.

The conclusion was that the Directive created an obligation for the ISP to implement blanket data retention, as it applied to a general public covering all possible means of communication.

The Australian Approach

Australia introduced data retention in 2015 with an amendment to the existing Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (the TIA Act), with a justification that it is necessary for counter-terrorism, counter-espionage, and fighting organized crime and serious criminal offences such as murder, rape and kidnapping, as well as for cybersecurity-related investigation. It was obvious that the convergence to Internet Protocol (IP) of telecommunications services will expand the scope of subscribers’ data in general. ISPs already have certain data retention practices within their business models, serving as the basis for billing. However, technological development created additional possibilities, and this is what the amendment was after. This bill was introduced with a clear apprehension of the importance for national security and law enforcement to be able to access subscribers’ metadata. One interesting argument in the explanatory memorandum for the amendment bill was the statement that covert investigation methods are more privacy-infringing than access to telecommunication data with consent.

The justifications were expanded to case studies to showcase the actual impact. Both on the Home Affairs website and in the explanatory memorandum, numbers and cases were highlighted to mark the importance of the data retention. The two comparative examples relate to the UK and Germany. In the UK, where data retention is practiced, it was possible to identify 240 out of 371 suspects using data retention in combination with other investigative techniques; whereas, only 7 out of 377 suspects were identified in Germany, where data retention regime was not practiced at the time.

Australia did its homework; they have learned from the argumentation of the CJEU. In particular, this amendment specified categories of data necessary for law enforcement and intelligence agencies with regard to their respective functions. It refined the scope of who can access the data and established an oversight regime by the Commonwealth Ombudsman (Chapter 4A from the Amendment bill of 2015). According to this data retention regime, the retained data should be encrypted, and the Government would provide financial assistance to the carriers and ISPs to meet their obligation under the amendment by 2017. It is important to highlight that the ISPs are not required to retain the content of the communication, such as web-browsing history or social media activity.

According to the same amendment, the data retention regime should be assessed by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) after three years of implementation (beginning April 13, 2017). The completion of the review is expected for April 13, 2020, if not extended.

The aim of the review is to investigate nine aspects of the legislation that include a) technological changes and feasibility of the current data retention mechanisms, b) costs related to implementation, c) number of complaints, d) security requirements and others. This review is a process that empowers and encourages involved stakeholders, including governmental and non-governmental organizations to express their opinion and concerns about data retention. For that purpose, a system has been implemented to submit statements.

The national data protection authority, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (the OAIC) submitted their recommendations to the PJCIS in 2019. They suggest reducing the retention period, introducing data destruction mechanisms, limiting the number of agencies that can access the data, consulting the Information Commissioner before the scope of the “enforcement agencies” and the “categories of data” is expanded any further, considering a warrant-based scheme for accessing the metadata and some other recommendations.

Among 42 statements submitted to the Committee, the very first is listed by the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC). Its statement annexes provide operational examples of how telecommunications data helps to establish connections and patterns, as well as help to rule out person(s). This statement can be found here.

The submitted statements are different in their nature: some justify the need for the data retention and some highlight the importance for strengthening oversight. For instance, submission No. 4, from the Faculty of Law of the University of New South Wales, talks about incompatibility of “bulk data retention” with the right to privacy. Another statement, the collective submission No. 19 from the Human Rights Law Centre, Access Now and Digital Rights Watch, was critical in its observations and recommendations. This statement pointed out that data retention was supposed to be used for serious crimes but instead became a tool for minor offences. They highlighted that, despite the argumentation that metadata is less intrusive, over the implementation it was proved that metadata can be nearly as sensitive as the content of communication. The fact that the TOLA arrived in 2018 and introduced voluntary assistance mechanisms by telecommunications providers and/or device manufacturers to decrypt communication, they thought this was a step closer to potentially ending up in mission creep, empowering surveillance and drifting toward criminalization of speech. It is worth visiting this statement for further details.

A worthwhile mechanism that the 2015 amendment for data retention regime introduced was the “journalist information warrants.” This mechanism protects journalists’ metadata from being accessed without a warrant. However, there have been worrying reports of abuse in the system.

It will be advantageous to learn if any changes will be in the pipeline after the review process is completed in Australia. Which recommendations will be taken into account and which will be ignored? Will there be any new course of action or will the framework remain intact?

Even if the Data Retention Directive has been abolished under the EU law, this doesn’t restrain individual EU member states from practicing data retention under their respective national legislations. But relevant existing or upcoming post-Digital Rights/Tele2 legislation should take action to undergo a review to comply with the conditions given in the CJEU judgment, or the latest can be challenged once more in the court. One could wish this was conclusive, but states are looking into options to restore a data retention regime within the EU once more. In 2019, the EU Council published its conclusion highlighting the need for data retention to fight crime.

The question we have to ask ourselves is: Do we want Armenia to prioritize a powerful state with mass surveillance ability or individual freedom and respect for privacy? Another question we must ask ourselves is whether we want to find a balance between these two options and what that could look like. What can Armenia learn from these examples?

These questions are left for an open discussion. Perhaps, the discourse should embark on whether or not there is a genuine need for data retention in Armenia.

also read

Logging Your Internet Activity: What's True and What's Not

By Harout Manougian

A draft document penned by an independent government regulator has raised important questions about digital privacy. Though the proposal definitely has issues, the rumors it sparked are alarmist and exaggerated.

A Country Where the Word Privacy Does Not Exist

By Samvel Martirosyan

Is Armenian society concerned about privacy or the protection of personal data? Samvel Martirosyan is doubtful.

Information Security or Cybersecurity? Armenia at a Juncture Again

By Albert Nerzetyan

As the world becomes increasingly connected, states are adopting national strategies to protect themselves against cybersecurity breaches. This article outlines the ongoing debate around the terms ‘information security’ and ‘cybersecurity’ and examines global developments, as well as, Armenia’s institutional and policy advancements.

listen to

Information security expert and co-founder of civicert.am Samvel Martirosyan speaks about a new bill that if adopted would oblige all Internet Service providers in Armenia to collect and store data on their subscribers and more.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.