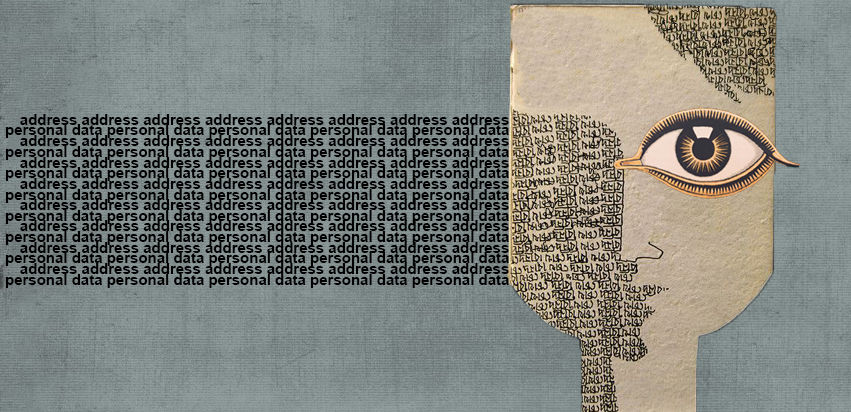

Armenia is a country where the word privacy does not exist in its official language.

The reckless approach to personal data in the country is rooted in its Soviet history, a time when everyone lived under the sleepless and watchful eyes of the KGB and when close relatives denounced each other’s ideological impurities to the state.

The Soviet days are thankfully behind us. However, attitudes regarding personal data have not meaningfully improved. In 2002, the Law on Personal Data was passed with the aim of regulating the field. However, the law was created and then forgotten. No sub-legal act or similar decisions were passed to actually regulate the field. It remained on paper.

Years passed. The world started talking about personal data and privacy more and more, especially as social media began opening up more of our lives to the world. Edward Snowden shocked the globe by revealing the extent to which the US National Security Agency (NSA) was able to peer into your online correspondence and activity. In Armenia, however, there was no reaction in calling for greater privacy protection. People discussed the situation over a cup of coffee and expressed shock at all the awful things taking place in the world.

In 2015, Armenia suddenly passed the Law on the Protection of Personal Data. Moreover, the Ministry of Justice created the Agency for the Protection of Personal Data. The agency works actively today and carries out public awareness campaigns.

However, the issue at hand is that the law once again remains toothless. It leaves many questions unanswered and does not create specific mechanisms to deal with breaches in privacy. Moreover, the current laws, for example, do not provide for effective oversight of companies that hold people’s personal data. Current laws include such inconsequential fines for violations that companies would prefer to be fined than to hire a security expert in the field.

Often, it’s not even clear what the law demands in cases that deal with new technologies. For example, there are many security cameras in Yerevan that record street traffic and allow the police to fine drivers that break the law. One day, I started to wonder: Who has access to this data? Who regulates the process? Where and how long are the recordings kept? How are they disposed of? I sent these questions to the company that operates these security cameras. Their answer was concerning and unspecific: everything is done according to Armenian law. The end.

Without timeline clarifications for data retention and destruction, there have been cases when personal data has become publicly-accessible through some other law. The most interesting case has to do with the voter registry used for elections.

On the Central Electoral Commission’s website, you can find the registry of Armenian voters, where you can input anybody’s name and last name to find out when they were born, the address where they are registered, as well as all their family members (or others) who are registered at the same address. This is extremely personal data that is accessible year-round from anywhere in the world.

What’s interesting is that this data is on the website because it is required by the Electoral Code. At the same time, however, it also contravenes the Law on the Protection of Personal Data.

The voter registry has been around longer than the 2015 Law on the Protection of Personal Data. There is a reason this registry exists: trust toward the election process in Armenia has historically been very low. Up until the last parliamentary election in December 2018, the opposition never accepted the results of the vote, considering them rigged (of course, other exceptions include the first Presidential election in 1991 that took place from which the history of independent Armenia was launched.) Everyone knew that people who had left the country or had deceased were supposedly “voting” during elections. The voter registry was created to prevent these “zombie voters” from taking part in the elections. It was to allow people to check these lists on their own and demand that people who did not have the right the vote be removed.

In any case, the data is on the web and for years this issue has not been resolved. Taking into consideration that the reckless approach to personal data is widespread, abuse of this data by a malicious actor is extremely easy. For example, by finding out a person’s address through the Central Electoral Commission’s website, you can go to the post office, provide “your” address and then feign a temporary lapse in memory of your phone number and nine times out of ten, the clerk will volunteer it for you. You will most likely have to pay the phone bill for that address, but you have conveniently revealed that person’s phone number. If you’re clever enough, then you could also potentially find out how much this person owes utility providers through any online utility payment portal. The list goes on.

Since the last amendments to the Electoral Code in 2016, the Central Electoral Commission has scanned and uploaded all the Election Day voter lists that include a voter’s signature, if they showed up to vote. This means that not only is their address and date of birth accessible through the website but a would-be impersonator even has easy access to a sample of their signature.

Clearly, Armenia has poor defenses against identity theft and the voter registry on the Central Electoral Commission’s website is a weak link. If the user entered their name, date of birth, and address, and the registry simply said Yes or No to whether they were on the voter list, it would do its job while not revealing information that the user did not already have.

also read

Logging Your Internet Activity: What's True and What's Not

By Harout Manougian

A draft document penned by an independent government regulator has raised important questions about digital privacy. Though the proposal definitely has issues, the rumors it sparked are alarmist and exaggerated.

Information Security or Cybersecurity? Armenia at a Juncture Again

By Albert Nerzetyan

As the world becomes increasingly connected, states are adopting national strategies to protect themselves against cybersecurity breaches. This article outlines the ongoing debate around the terms ‘information security’ and ‘cybersecurity’ and examines global developments, as well as, Armenia’s institutional and policy advancements.

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.