Mon Sep 06 2021 · 22 min read

Was China All Innocent During the 2020 Artsakh War?

By Paruyr Abrahamyan

Comments

Aslan Aslanov

11/13/2021, 5:34:31 AMNice analysis. But you should watch Putin's interview once again. Putin said that former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast is part of Azerbaijan according to the international law. Thus Putin was not referring to the 7 district around Nagorno Karabakh but to the former Oblast itself. The fact that those 7 districts were part of Azerbaijan was never a question. Therefore he appropriately mentioned the former oblast

Todd Fabacher

9/12/2021, 6:11:28 PMI agree with many points here. It is a well thought out article and explains why many of the countries did nothing to help Armenia. The only problem is most countries will not help other nations in self-determination because it is against their own interests. But thinking any other country in Europe or the United States will put in peacekeepers or risk any lives to protect Armenia is wishful thinking. The final conclusion is simply flawed, the "West" will just watch you die and offer new places for the refugees to start new lives in their own country. It is better to have educated Christian Armenians than Muslims as refugees to help add to their declining populations. There is no savior behind the curtain - ONLY Armenia will save itself. The country needs a little from all payers Europe + Russia + USA + China + Iran + the Middle East + India and it needs to make itself relevant to each player. To just play the "Poor Armenia" card will result in dead Armenias with a lost country. Countries do what is in their best interest. What has Armenia done for China that would make it risk people and foreign policy norms to stick its neck out for Armenia? Or France? If you think the USA will ever put boots on the ground, you are living in fantasy land. The main flaw is that it is assumed Armenia must turn east or west. There are many countries that understand realpolitik and do what is in the best interest. Isreal is one. This is why they calculated that Armenia does not serve any national interest for them, and simply they sold you to the wolves. You did not even mention them in your article and they were the prime supplier of weapons behind Turkey. I agree with the article and many [not all] of the facts. But the conclusion to turn West is a deadly mistake. We don't live in the Cold War anymore. The world is multi-polar, so my suggestion is to begin to understand that and create a foreign and economic policy accordingly.

Ben Roth

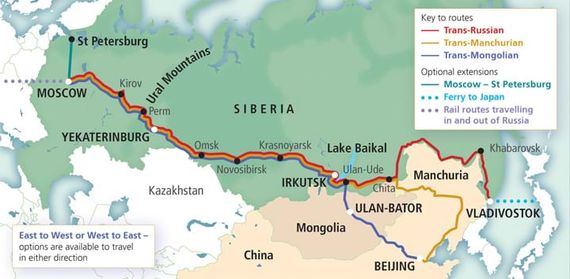

9/9/2021, 9:21:15 PMThere is no question, Armenia is between a rock and a hard place. Russia is looking to not irritate its Muslim citizens and the old SSRs that are now independent countries. China is looking at as many ways as possible that it can get its goods west. The west is playing spectator. While no two situations are alike, Armenia is in a similar situation to what Israel faced when it came into being. To this end, Armenia must have the full support of its diaspora and it must set out to build an economy and a defense capability similar to the Israeli's. It faces very long odds, Its neighbors Turkey and Azerbaijan want it destroyed/wiped from the face of the Earth. Iran in its own way is in the same boat, it has few friends. However, Armenians and Persians have gotten on well for a long tome. On the negative side, most of diaspora is in America and it does not get on well with Iran for a long time. That leaves Georgia and they've got the Russians to constantly worry about. Not promising. A journey of a million steps starts with a single step. Fund raising must begin in earnest, the initial goal has to 0.5 billion annually. in terms of defense, needs to build in-house capabilities. The biggest bang for the buck coms from BMC4I systems. Small arms, AK-47s are cheap and maybe the best assault rifle ever made. Everyone learns to really shoot the really talented get 50 Cal sniper rifles. . Air space, drones, drones, drones for everything. Develop (in-house) anti drone capabilities. Possibly, there might be markets in Iran and Afghanistan. Use the diaspora to identify what people want in the US, Europe, Australia, South America. If not already being done, grow for export to Russia, just like the old days in the USSR. These are just generalities to prompt real thinking and plotting long term while getting prepared for what could happen at any time.

maro Matosian

9/9/2021, 4:30:34 PMthis is such a well written, well analyzed and important article. Many thanks.

Gabriel Armas-Cardona

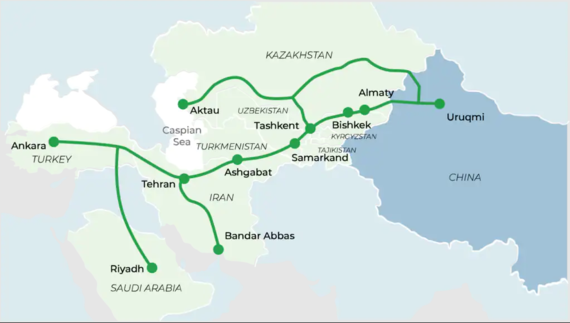

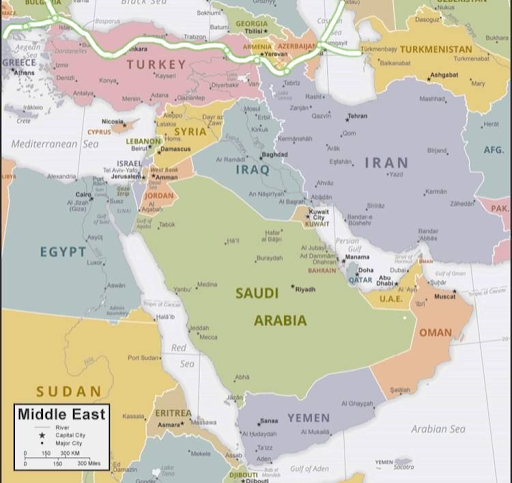

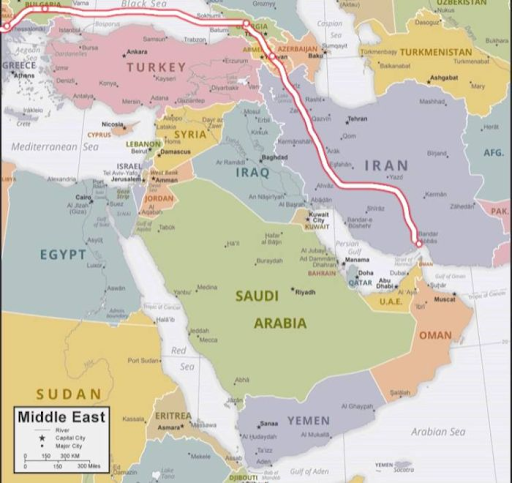

9/7/2021, 12:36:47 PMOverall, a very well researched and thorough article. Bravo. My concern is that I think the author's strong opinions limit the author's consideration of alternatives. While Turkey might prefer this middle path, why would China give up so easily on the Southern route? Iran and China signed a $400 billion agreement just a year ago, making it seem like Iran will be an important component of China's infrastructure project. Promoting cooperation between Iran and China will also deny Iran becoming close to India, China's regional rival. It may (or may not) be significant that a quick google search on the middle path brings a lot of articles from 2018 and 2019, before China signed the deal with Iran. Even if this middle path is made into a priority, the author doesn’t give enough consideration to Georgia as a transit country. The reasons the author rejects Georgia are because it’s a 1) “Western-bastion” and 2) its ongoing frozen conflicts. Reason #1 doesn’t seem so important; the point of BRI is to bring goods to Europe, something that the EU supports. While the US won’t like it, Georgia is not a client state of the US. If the EU wants to trade with China, then they’d prefer more transit through EU-aligned states. Reason #2 is not so convincing either. The frozen conflict is in the North of the country while the transit system would go through the South. While it’s possible for Russian forces to take control of land that so far (as they almost did in 2008), what would be the point except for all out war? If China truly fears Russia might interfere with its transportation connection, then why in the world would China agree to traveling through Syunik where Russia is both the owner of the transit system and the security guarantee?

Wally Sarkeesian

9/6/2021, 6:05:35 PMGreat Article well researched and well-articulated, however, I am sorry to say with these complicated geopolitics and having a Government in Armenia made of an incompetent, inexperienced street activists in control of all branches of the government... it is a hopeless situation for Armenia.