The November 10 ceasefire agreement ended the 2020 Artsakh War but the issue of demarcation of new state borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan has been a major concern since then. You can now see Azerbaijani soldiers across the eastern border of Armenia’s southern Syunik region. Just a few months ago, that area was administered by the Republic of Artsakh, but they were lost in battle or handed over as part of the truce agreement before the end of the year. As concerns about the legitimacy of the demarcation and delimitation process keep piling up in the public discourse, there is an increasing need to go back in time to better understand the present.

հայերեն

Սահմանագծման խնդրի արմատները

Early Years of Independence

The roots of the issue of the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan can be traced back to 1918, when Armenia’s First Republic and the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic were established. According to Rouben Galichian, a researcher specializing in historical maps of Armenia and the South Caucasus, the maps from the period indicate that, even back then, Azerbaijan had ambitious plans and claimed ownership over Karabakh (Artsakh), Zangezur (Syunik) as well as the Karvachar (Kelbajar) and Lachin regions.

Until the end of May 1918, Karabakh was part of the Elizavetpol Governorate (guberniya, in Russian) of the Russian Empire. Following the founding of Azerbaijan, the local ruling elite declared their territory to cover both the Baku and Elizavetpol Governorates. Shushi, which was a major Armenian cultural center in Karabakh, was predominantly populated by Armenians. In 1917, over 23,500 Armenians lived in Shushi. This number would drastically decrease over the next several years, most notably after the 1920 Shushi massacre in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide.

In late November 1918, General Andranik Ozanyan’s forces headed toward Shushi, determined to liberate the city and fully ensure the security of Karabakh. In early December, when Andranik’s forces were only 40 kilometers away from Shushi, he received a message from British General William Montgomerie Thomson, who was the military governor in Baku at the time.

General Thomson suggested that Andranik should retreat from Karabakh because World War I had just ended and the continuation of hostilities would have had negative implications for the solution of the Armenian Question, which was expected to be discussed during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. He also explained that the issue of Karabakh and Zangezur would be decided at the Conference. Galichian noted that the British General promised that those territories would eventually be handed over to Armenia through peaceful means, and that military intervention was not necessary. Andranik left his mission incomplete and returned to Goris, but as history showed, the British General did not keep his promise.

Soviet Period

The new Azerbaijani and Armenian republics were short-lived; only two years after their independence, they were sovietized in April and November 1920, respectively. Following the establishment of the Soviet rule, the interim Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan (the main Bolshevik governing body at that time) declared that the “disputed territories,” namely Karabakh, Zangezur and Nakhichevan, were inseparable parts of Armenia, as they were predominantly populated by Armenians. This decision was announced in the newspapers of Moscow, Baku and Yerevan, and reaffirmed by Joseph Stalin, upon his visit to Baku in July 1921. But a day later, the decision was reviewed under Stalin’s direct interference: Karabakh was incorporated into the territory of Soviet Azerbaijan, with only a portion of it designated the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. Nakhichevan (which had been part of the Erivan Governorate during the Russian Empire) was also annexed to Azerbaijan and given the status of an Autonomous Republic.

In 1923, Azerbaijan had a plan to establish a neutral province, acting as a buffer zone between Armenia and Azerbaijan, under the name of Red Kurdistan, which would have provided a physical divide between the two counties and curbed the existing tensions. Galichian noted that the plan entailed the handover of Karvachar (Kelbajar), Lachin and some parts of southern Soviet Armenia, to Soviet Azerbaijan, as lands for the Red Kurdistan province. He went on to say that “Soviet Armenian officials did not resist the proposal, despite the fact that it meant having Karabakh surrounded by Kurds.” At the time, between 30,000 to 35,000 Kurdish people lived throughout Azerbaijan. With this justification, over 1,000 square kilometers of strategically important territories from Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh were handed over to Azerbaijan between 1928 and 1930. Thus, the borderline between Armenia and Azerbaijan that was marked in the late 1920s was much different from the borders that were marked upon the sovietization of both republics in 1920.

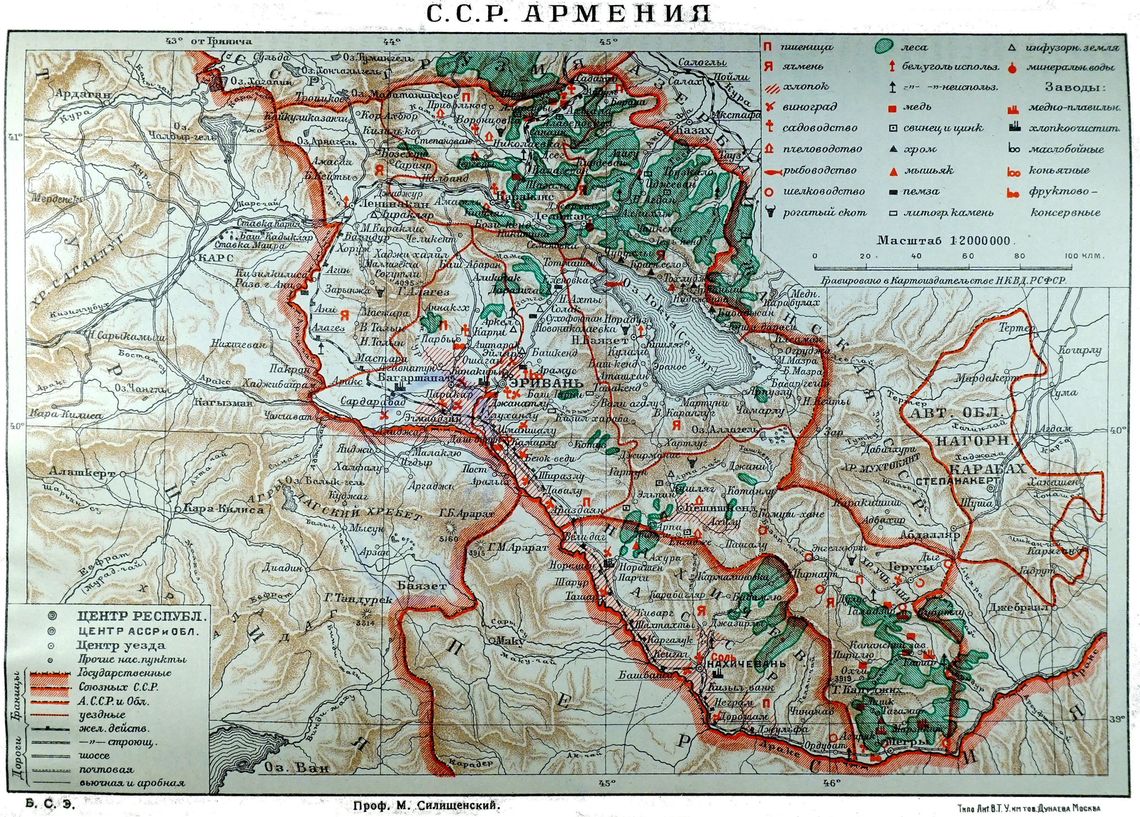

Map 1

Between 1930 and 1934, some territories were ceded to Azerbaijan under the pretext of the establishment of the Red Kurdistan region. These lands are shown on Map 1, highlighted in blue, and include Larger and Lesser Al Lakes, other pastures, and parts of Lachin. As a result, the contiguous corridor between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh was eliminated. These territories also include parts of Shurnukh village, the area southeast of the city of Kapan (then called Ghapan), and territories east of the city of Meghri, near the border with Iran.

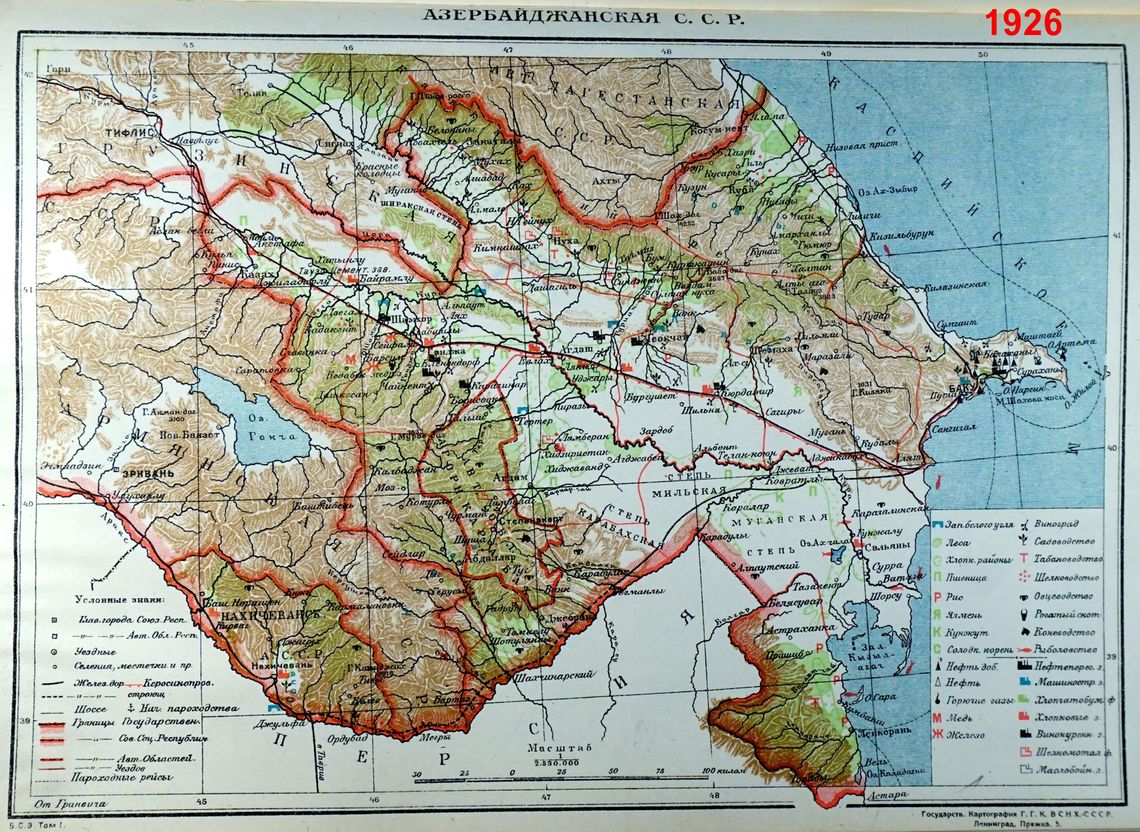

Map 2

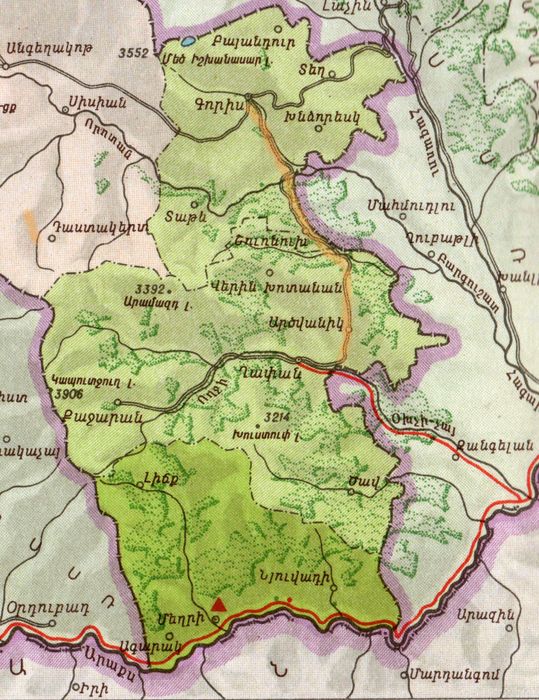

Map 3

Maps 2 and 3, which are from a Greater Soviet Encyclopedia, reflect the borders of Soviet Armenia and Soviet Azerbaijan as of 1926. Both maps clearly indicate that Al Lakes and Shurnukh village were part of Armenia’s territory, Kapan was at least ten kilometers away from the border with Azerbaijan, and Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh were connected through the Lachin corridor. Galichian stressed that Soviet Armenian leadership did not raise concerns about this arbitrary decision. “Without an official demarcation and delimitation of the borders, the maps of the Soviet Union were adapted to reflect the territorial changes and the new borderline between Armenia and Azerbaijan,” added Galichian. However, he went on to note that, throughout the Soviet period, Armenian maps were not modified to reflect the changes of the borderline between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the late 1920s. The Goris-Kapan road is a case in point.

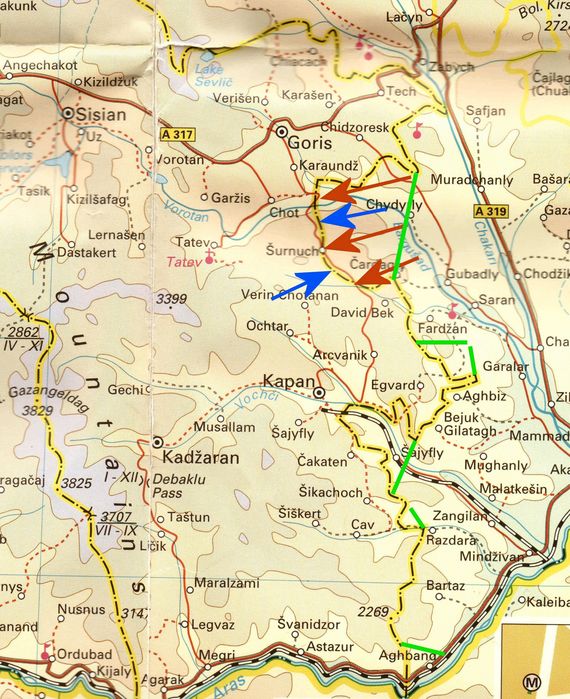

Map 4, which is from a Soviet Armenian atlas, displays the village of Shurnukh as completely under Armenia’s control. While Map 5, which is of Canadian origin and depicts the same road, displays how the road and the border actually pass through Shurnukh village. Galichian stressed that, although territories were given to Azerbaijan, “Soviet Armenian authorities kept hiding the truth from their own people and presenting a distorted version of reality through the maps.” He went on to note that the roots of the current demarcation issues are the expected outcome of the decisions made in the 1920s.

A month after the November 10 agreement was signed, the demarcation of state borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan was initiated. As a result, the defensive positions of 13 villages of the Syunik region near the city of Kapan were handed over to Azerbaijan. Twelve houses in Shurnukh village ended up under Azerbaijani control.

According to archival materials published by Arman Tatoyan, Armenia’s Government Ombudsman, the handover of Al Lakes and adjacent pastures was justified by the needs of the nomadic pastoralists of the Kurdish province. Soviet Azerbaijani authorities applied to the Soviet Union claiming that Kurds do not have enough pasture because the territory is predominantly mountainous. In November 1930, after the territories were given to Azerbaijan, local Armenian authorities sent a letter to the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union requesting a review of the decision. The letter stressed that the ceded territories with their geographic location and water resources were completely isolated from Soviet Azerbaijan and were the natural continuation of Basargechar, which is in the southeast of the current Gegharkunik region.

The response was very clear: the decision was not going to be reconsidered. In 1930, when the idea of establishing Red Kurdistan was abandoned, all of the Armenian territories remained under Soviet Azerbaijani control.

During the First Karabakh War in the 1990s, Armenia regained control over some of the territories, and Armenians started building their lives in those areas. Galichian noted that people should have been informed about the consequences that could potentially have come up (and now have) in the future.

Demarcation and Delimitation

During Soviet rule, demarcation and delimitation were simply not carried out between the member states. According to Galichian, Armenia became a member state of the United Nations in 1992, with the borders that it had during the Soviet Union.

After fourteen years of negotiations, in September 2010, Russia became the first of Azerbaijan’s Caspian neighbors to have reached an agreement on the delimitation and demarcation of borders. The process with its northwestern neighbor Georgia started in 1996 and still has not been completed. The border between the two countries stretches for over 480 kilometers. 314 kilometers have already been agreed upon, with negotiations yet to be concluded for the remaining 166 kilometers.

Map 4

Map 5

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Armenia and Azerbaijan could not have possibly demarcated the state border because of the ongoing conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. It was only after the 2020 Artsakh War that, for the first time since the 1920s decisions, the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan in this area started to be officially demarcated.

Issues exist not only with the border with Azerbaijan, but also with Georgia because the demarcation process has not been completed there either. None of the former members of the Soviet Union have fully completed their border demarcations. When a demarcation process takes place, concrete block-markers are installed to clearly mark the borders. Such concrete has now been placed in certain parts of Shurnukh village but not in other parts of the border.

Arman Tatoyan said that the demarcation and delimitation of Armenia’s state borders cannot be done using GPS. He said that there are many versions of online world maps, and that it is unclear which one is being used as the basis for the demarcation. He also noted that such processes require official commissions, preparatory work and can take decades. International standards for the demarcation and delimitation of borders put human rights and the rule of law at the core of the process and today, there is ambiguity, especially for the people who live in those areas. Galichian clarified that GPS technology is just a tool in the process. It is used to maintain accuracy between maps and the land they are supposed to represent.

Maps courtesy of Rouben Galichian.