Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Nikol Pashinyan renewed his parliamentary majority through Sunday’s June 20 early parliamentary election and will keep his position as Prime Minister of Armenia. It was a historically competitive campaign, leaving most of the country unsure of what to expect, even as the first results began coming in late in the evening.

The two dominant forces were Nikol Pashinyan’s Civil Contract Party and Robert Kocharyan’s Armenia Alliance, consisting of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and the Resurgent Armenia Party. A breakdown of the different parties that participated is available in a previous article. However, the end result was not close, as Civil Contract took an outright majority of 54% of the vote nationwide. Only in Yerevan did they dip below 50%, but still finished solidly in first place there as well. The Armenia Alliance posted its strongest showings in Yerevan and Syunik region, where they collected 27%.

In a February 2021 survey by the International Republican Institute (IRI), only 10% of respondents said that they felt familiar with the mechanisms by which the National Assembly is elected. Although those mechanisms have been simplified since then, notably through the elimination of the regional open lists, there was still a gap in understanding of what the election results meant.

One such misunderstanding is associated with the 54% stable majority provision. One Russian-language source suggested that Civil Contract (which received 53.96% of the vote) had fallen just shy of the level required to form a government, a very wrong assessment. Armenia’s Constitution entrenches the concept that the Electoral Code must ensure a “stable majority” through holding a runoff election if no coalition can be formed. While the Electoral Code defines a stable majority to be 54% of the seats (soon to be reduced to 52% after recent electoral reforms come into force in 2022), the threshold to form a government is 50%+1 of the total seats. If a party or coalition gets to that point, they receive additional bonus seats to top them up to 54% (so that the government doesn’t fall if one MP is on an official visit or in the hospital).

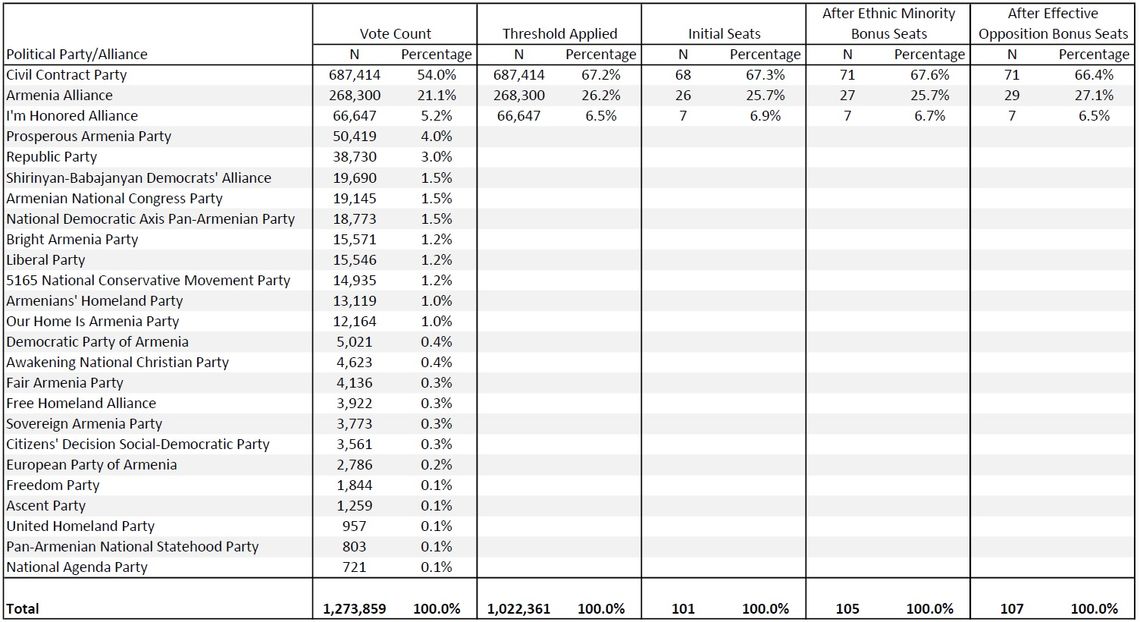

Furthermore, the percentage of the vote that a party receives and the percentage of the seats they get are not identical, due to 1) the electoral threshold, 2) ethnic minority bonus seats, and 3) stable majority/effective opposition adjustments.

The Electoral Threshold

In order to receive any seats in parliament (the legal phrase is “participate in the distribution of mandates”), a political party needs to receive at least 5% of the valid votes cast. Ahead of the 2007 election, this threshold was set at the higher level of 7% for alliances of multiple parties contesting together with a joint candidate list.[1] However, if less than three parties or alliances meet the threshold, the top three are included in the distribution of mandates regardless.

The results of the 2021 election showed that only the Civil Contract Party and the Armenia Alliance met the threshold. At 5.2%, the I’m Honored Alliance was just short of the alliance threshold of 7%, and at 3.96% the Prosperous Armenia Party (PAP) fell just short of the party threshold of 5%.

As the I’m Honored Alliance had more total votes, the threshold was waived for them so that there would be at least three forces participating in the distribution of mandates. However, if the PAP had met 5%, with three parties or alliances passing the threshold, the I’m Honored Alliance would not participate in the distribution of mandates, even though they might have had more votes than the PAP. That is the cost of running as an alliance.

Beginning in 2022, these thresholds will be adjusted. For political parties, it will be reduced from 5% to 4%. For alliances of two parties, it will be increased from 7% to 8%. For alliances of three parties, it will be increased to 9%, and for alliances of four or more parties, it will be increased to 10%. In 2021, the only alliance with more than two parties was the Free Homeland Alliance, which consisted of five parties. The purpose of the change is to encourage more permanent party consolidation, rather than smaller person-based parties only temporarily cooperating immediately before an election.

The Prosperous Armenia Party and Bright Armenia Party could have insisted that the lower 4% threshold apply to this election, a policy all sides have had consensus on since 2018; however, they decided to sit out the discussions on amending the Electoral Code and the governing Civil Contract Party found it prudent to delay its implementation into the future. The original 5%/7% threshold still applies to the 2021 election and the eighth parliament of the Republic of Armenia.

Any parties or alliances that did not meet the threshold are taken out of the total. For the 2021 election, one in five valid votes, 19.7%, are disregarded for this reason, and the initial proportional allocation of seats is based only on the smaller sum of the votes remaining. The impact is that the percentage of seats that parliamentary parties receive are higher than the percentage of the total vote they collected, as shown in the table below.

Thus, the initial 101 seats are distributed (using the greatest remainder method) as follows:

-

Civil Contract Party: 68 seats

-

Armenia Alliance: 26 seats

-

I’m Honored Alliance: 7 seats

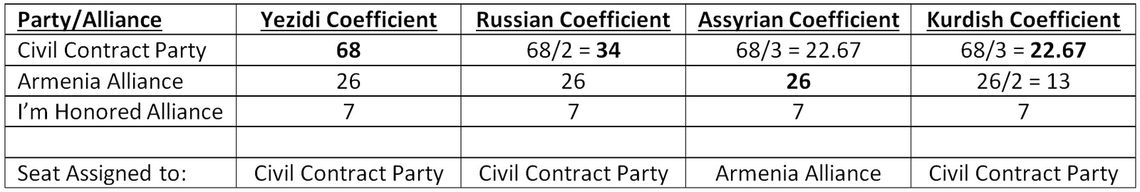

The Ethnic Minority Seats

The 2015 Armenian Constitution guarantees that ethnic minorities will receive reserved seats in parliament. The Electoral Code specifies how this occurs. It is important to note that the ethnic minorities themselves do not get to decide who represents them, however. That is left up to the political parties who decide which candidates to nominate, and the final vote total (decided mostly by the ethnic Armenian majority). A previous article explains the D’Hondt formula used to allocate which parties get which ethnic minority candidate elected, a process that is not completely random but not tied to any particular principle of representation.

The vote distribution among the top three parties yields a result where the Civil Contract Party’s Yezidi, Russian and Kurdish candidates (all the current incumbents) get re-elected, while the Armenia Alliance’s Assyrian candidate is elected. It is worth repeating that the choices of Armenia’s ethnic Assyrian voters had zero relevance to this result, it is purely the outcome of the Assyrians being the third-largest minority and the ratio of total votes between the Civil Contract Party and Armenia Alliance being roughly 2:1. The calculation is shown in the table below:

It is recognized that the way ethnic minority seats are distributed, especially as they come after the initial proportional allocation of seats to parties instead of being embedded within it, is problematic. The issue was discussed during the electoral reform process but left untouched because the incumbent ethnic minority MPs (who were elected by it in 2018 and held crucial votes to pass the final amendments with a three-fifths majority) were satisfied with it.

Note that, among the 25 participating parties and alliances, only five nominated any minority candidates. The Civil Contract Party was the only one to nominate a candidate from all four of the largest ethnic minorities. If the I’m Honored Alliance, which had not nominated any ethnic minority candidates, had been allocated a seat through the formula, they would have actually lost the seat to another party. Also, as no party nominated alternate ethnic minority candidates (they are permitted up to four for each of the four minorities), if any of the four elected MPs were to lose their seat for any reason (resignation, death, appointed as a cabinet minister, etc.) their seat will be left vacant, reducing the size of their party’s caucus and parliament as a whole.

After including the ethnic minority MPs, the seat count is adjusted as follows:

-

Civil Contract Party: 71 (68+3) seats

-

Armenia Alliance: 27 (26+1) seats

-

I’m Honored Alliance: 7 seats

The Effective Opposition Provision

Armenia’s Electoral Code does not allow any single political party or alliance to receive more than two-thirds of the seats. If this were about to happen, the size of parliament is increased, with additional bonus seats being allocated to the opposition parties that passed the threshold.

As the Civil Contract Party would have 67.6% (71/105) of the seats, this provision is triggered, as it also was during the 2018 parliamentary election. Adding one additional seat would leave Civil Contract with 67.0% (71/106), which is still greater than two-thirds (66.667%). Thus, two additional seats need to be added, leaving Civil Contract with 66.4% (71/107) of the total, which is slightly less than two-thirds.

There is no such thing as adding half a seat, and that is where the significance of ending up with an odd number of seats works to one’s disadvantage. In 2018, the My Step Alliance took 88 of the first 105 seats, which led to the size of parliament being increased to 132, leaving them with exactly two-thirds of the total. With that number, they were able to pass measures that required a two-thirds majority, including a constitutional amendment impacting term limits on the Constitutional Court.

However, now with 71 seats, an odd number, after the two effective opposition bonus seats are added to raise the total to 107, the Civil Contract Party will not have a two-thirds majority but ever-so-slightly less. The impact is quite significant, as they would need to convince at least one opposition MP to vote with them to pass any measure that does require a two-thirds majority.

In hindsight, the provision should be rewritten to always water down a dominant party to “less than two-thirds” rather than “not more than two-thirds” as its underlying intention is to facilitate compromise and consensus.

Under the current arrangement, there is a “what-if” scenario that exposes the weaknesses of the existing Electoral Code. If the Civil Contract Party had not nominated a Kurdish ethnic minority candidate, no other party would have received that seat; the total number would be reduced from 105 to 104. The only other party to nominate a Kurdish candidate[2] was the Armenian National Congress Party, which did not pass the threshold and is not eligible for any seats. In this scenario, Civil Contract would have 70 (an even number) out of 104 seats before the effective opposition clause kicks in. That clause would grant only one additional seat to the opposition, leaving Civil Contract with exactly two-thirds of the total (70/105), rather than slightly less. Hypothetically, the Civil Contract Party could pressure Knyaz Hasanov, their Kurdish candidate, to withdraw his candidacy before the Central Electoral Commission officially performs the seat distribution calculations, in order to leave the party in a better position overall. If he were to withdraw after this calculation, the opposition would still keep their two bonus seats. Good electoral design would not allow these kinds of perverse incentives to exist, even if they are unlikely to be acted upon.

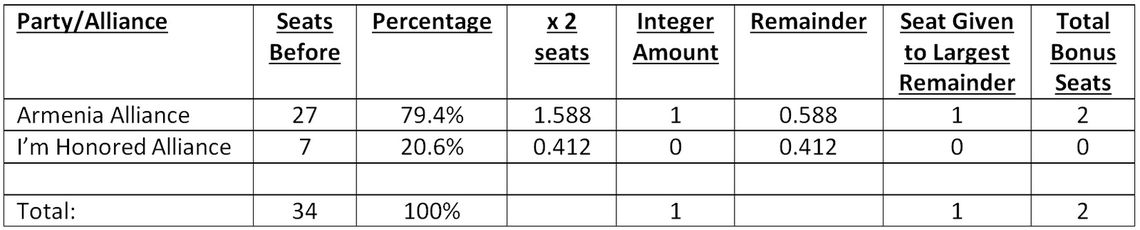

Assuming such games are not played, there will be two effective opposition bonus seats. They are distributed proportionally among the opposition parties that passed the threshold, using the greatest remainder method. The table below shows how the Armenia Alliance takes both bonus seats.

After including the effective opposition bonus seats, the seat count is adjusted as follows:

-

Civil Contract Party: 71 seats

-

Armenia Alliance: 29 (27+2) seats

-

I’m Honored Alliance: 7 seats

The effective opposition provision was reviewed by the Parliamentary Working Group on Electoral Reform. The group had decided that, in the future, such additional mandates required to water down the majority to two-thirds should be given to the parties that had been left below the electoral threshold, rather than increasing the clout of the parties that had already passed it. The version of the electoral reform amendments submitted to the Venice Commission reflected this approach.

However, the version that was ultimately passed eliminated the effective opposition provision altogether! The change was made silently in a session of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on State and Legal Affairs on May 6, hours before the bill passed its necessary two readings that evening and the next day. No public consultation on removing the provision was conducted. Despite the provision being triggered in two of the three elections since it was introduced, unless the Electoral Code is amended again, the 2021 election marks the last time the governing party will be limited to a two-thirds majority.

Refusing Seats

There have been murmurs that perhaps the Armenia Alliance and I’m Honored Alliance could refuse their seats in order to throw a wrench into the functioning of parliament and force a new election. Just boycotting parliamentary sessions alone would not be sufficient. In order for a parliamentary session to have a quorum, a majority of members need to check-in when it begins. Both the Prosperous Armenia Party and Bright Armenia Party boycotted several sessions of parliament in the aftermath of the 2020 Artsakh War, but the government continued its work with its own MPs.

Actually refusing to take up the mandates to begin with is different from boycotting parliamentary sessions. In this case, the candidates never agree to become an MP. It would be a risky, unprecedented move. Such refusals happen by each individual candidate, through notarized declarations submitted to the Central Electoral Commission. When a candidate refuses their mandate, it is allocated to the next candidate down the party’s list. The Armenia Alliance has 153 candidates on its list and the I’m Honored Alliance has 230. If any of those individuals decides that they do want to become an MP (the party can pressure them but not force them to withdraw), they are legally entitled to that seat.

If all of them refuse their mandates, the Electoral Code specifies that those seats are left vacant. The only way to trigger an election, according to Article 92 of the Armenian Constitution is to fail to elect a Prime Minister after two attempts, or to fail to approve two consecutive Prime Ministers’ government programmes. The ruling party, with its majority, can conduct parliamentary sessions alone, vote in the Prime Minister alone and approve the government programme alone. The only wildcard is that Article 89 of the constitution specifies that the National Assembly be made up of at least 101 MPs.

There are Election Dispute Resolution (EDR) processes established for submitting specific complaints about electoral violations and appealing specific precinct vote totals, with the Constitutional Court as the ultimate authority. If instead the two new opposition parties decided to roll the dice and use the minimum 101-seat requirement as the basis of their legal argument, if they were able to convince each of their 383 candidates to go along with it, they take the risk that the Court may decide the remedy to be allocating those seats to the opposition parties that received less votes. That would overrule the Electoral Code, which specifies the seats should be left vacant. But setting the remedy to be a new early election would overrule the Constitution itself, which is very specific about the conditions under which an early election is called, and MPs refusing to take the job is not one of them.

Also see

Armenia Votes: Live Updates

As Armenian citizens head to the polls to vote in an early parliamentary election today, the country is bracing itself for one of the most unpredictable election outcomes since independence. Live updates from Election Day.

Remedial Secession in the Programs and Statements of the Political Forces Competing in Armenian Elections

By Sossi Tatikyan

After the shocking defeat in the war, the use of the notion of “remedial secession” has not been consistent, neither by the authorities nor by other political forces in Armenia. Sossi Tatikian explains.