Tue Jun 15 2021 · 10 min read

Remedial Secession in the Programs and Statements of the Political Forces Competing in Armenian Elections

By Sossi Tatikyan

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

The notion of remedial secession (in Armenian, “Անջատում հանուն փրկության'' literally meaning “secession for salvation”) has been featuring in the context of Armenia’s ongoing election campaign. In particular, Nikol Pashinyan’s Civil Contract Party has mentioned it in its party platform in generic terms as a basis for resolving the Artsakh conflict, without elaborating its mechanism. Alen Simonyan, a senior Civil Contract figure, referred to it during the first televised election debate when the representative of the Armenian National Congress Party, Arman Musinyan, brought up that his party leader, first President Levon Ter-Petrosyan, was the first to invoke that doctrine. Artak Zeynalyan, representing the Republic Party, in turn mentioned that their party has developed a version of that concept and presented it to the previous authorities, which was a revelation not known to the public. However, the notion of remedial secession is not featured in the published platforms of the Armenian National Congress Party or Republic Party. Moreover, when asked about it in a press briefing on June 10, Levon Ter-Petrosyan reiterated that he had indeed creatively translated the international term “remedial secession” that had been applied to Kosovo; but he also regretfully mentioned that, while the notion was applicable when he suggested it in 2016, it would be “laughable” to consider for the post-war situation in Artsakh.

In general, the Armenian National Congress Party has positioned itself as a realistic programmatic political force. It is not a new positioning; it is consistent with the party’s previous pronouncements since 1997 on the issues related to the resolution of Artsakh conflict and Armenia’s foreign policy. Ter-Petrosyan was also instrumental in laying the foundation of the negotiations over the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the principles of the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and the right to self-determination of Nagorno-Karabakh, criticized by some other political forces such as the National Democratic Axis that believes the foundation of negotiations has to be the restoration of Armenia’s territorial integrity through the reunification with Artsakh.

The contradiction of the principles of territorial integrity and self-determination is one of the most difficult dilemmas in international law, mostly resulting in deadlock in favor of territorial integrity. However, there have been cases where the notion of remedial secession has been applied based on the existential threat of ethnic cleansing, including the cases of Kosovo, Timor-Leste and South Sudan. When Ter-Petrosyan was in power, the notion of remedial secession was not yet fully articulated. It rose to prominence more clearly in the context of the NATO intervention and establishment of the UN Mission in Kosovo in 1999. At the same time, he had referred to the existential threat of ethnic cleansing that loomed over the Armenian population of Artsakh in his statement at the Lisbon Summit in 1996, referring to the history of massacres and deportation of Armenians incited by Azerbaijan.

By its nature, “remedial secession” is not a realpolitik interest-based notion but a liberal value-based notion, justifying secession of the given entity, as well as intervention on the part of the international community toward that end, from the point of view of international human rights and humanitarian law. Thus, the suggestion to apply that principle to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict by Levon Ter-Petrosyan in an article published after the 2016 Four Day April War was a deviation from the usual realpolitik approaches of his party in favor of liberal notion in order to break the deadlock and find a solution. It was further developed by Ruben Shugaryan, a former Deputy Foreign Minister and Armenian Ambassador to the U.S., also associated with the Armenian National Congress, who modified it to the notion of “remedial recognition” in an article published in 2016. “Remedial recognition” was used to better tailor the notion of “remedial secession” to the situation in Artsakh.

The term “remedial secession” was used and debated during the 2020 Artsakh War. On October 8, 2020, Ter-Petrosyan wrote an article about it, referring to the decision by the Geneva City Council on October 7 claiming that self-determination is the only way to ensure the security of the people of Artsakh. He referred to his article from 2016 and insisted that it was vital for Armenian diplomacy to apply this principle. Prime Minister Pashinyan started using the notion of “remedial secession” in his statements and interviews in mid-October, before the reported breakdown in negotiations on October 19, 2020. The Armenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Members of Parliament were interchangeably using the hashtags “remedial secession” and “remedial recognition” throughout the war.

Apart from political forces, several Armenian experts referred to the notion of “remedial secession” in their interviews and articles as the way out of the conflict, such as specialists in international law Yeghishe Kirakosyan and Levon Gevorgyan, who are also part of the Armenian representation to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), Philippe Raffi Kalfayan, as well as myself. The justification for suggesting this resolution in the middle of war was the use of mercenaries, the constant shelling of the civilian population and infrastructure with cluster munitions, ballistic missiles and rocket launchers, the mutilation and decapitation of civilians and prisoners of war, as well as the history of past massacres before and during the First Karabakh War. I also elaborated, building on Shugaryan’s article, that the modified version “remedial recognition” suited the Artsakh situation better than the original “remedial secession” for three reasons: First, according to the prevailing Armenian approach, Artsakh has not been a legitimate part of independent Azerbaijan but was forcibly incorporated into it by the Soviet authorities under Stalin's direct interference and had declared independence in line with the Soviet legislation still in 1991. Secondly, it had its permanent population and defined territory, and had established its governance bodies and institutions, thus matching three of the four main criteria for statehood in line with the Montevideo Convention on Statehood of 1933. In the immediate aftermath of the war, a group of Armenian-Canadian experts published a case for the application of the principle of the responsibility to protect (R2P) for Artsakh, including also to the notion of the “remedial secession.”

There was a political discourse over the notion of “remedial secession” or “remedial recognition” on social media, public and private discussions during the war by experts, different political forces and other citizens. While most liberals were in favor of the notion, those who were considered conservative or nationalistic were bringing arguments against it or posing questions. Most of those arguments continue to be articulated in the aftermath of the war.

The prevailing counter-argument was the lack of faith in the applicability of that principle to Artsakh, based on the belief that the U.S. and most of the European Union states supported Kosovo not out of liberal values and humanitarian intentions but hidden realpolitik interests.

A number of political and public figures and experts express concern that applying the principle of remedial secession means first acknowledging Artsakh as a part of Azerbaijan. On a relevant note, some claim that the term “secession” could be associated with the term “separatism,” which has a negative connotation in the international arena. However, its modification to remedial recognition would resolve that problem. Moreover, remedial rights were also practically applied to Timor-Leste, while it had not been a legitimate part of Indonesia but was annexed by it after decolonization by Portugal and its subsequent declaration of independence. For this reason, Timor-Leste refers to its national day as its “restoration of independence.”

Others claim that applying this principle would be a mistake, on the basis that Artsakh should be united with Armenia and not remain independent. This issue could be solved through declaring “remedial reunification” based on two arguments: First, the illegality of Artsakh’s initial integration into Soviet Azerbaijan and secondly, the non-viability of an independent Artsakh due to its small size and hostile geopolitical environment. However, it would be reckless to make this case in the heat of war. It should have been prepared during peacetime, based on presenting a legal package to international legal institutions to seek a conclusion similar to the International Advisory Opinion on the Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo by the International Court of Justice in 2010.

Those associated with political parties that were against the return of the 5+2 territories surrounding the Soviet-era Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) were bringing the argument that, while applying this notion, Armenia would lose those surrounding territories. However, the defeat in the war significantly increased the number of the people in Armenian society who now hold that it would have been reasonable to have returned five of those territories. As for the remaining two – Lachin and Kelbajar, it’s possible that they could have been kept as two alternative corridors, especially if the Armenian heritage in those two regions could be proved.

The same factions were usually against the establishment of an international peacekeeping mission, as they either thought that the Armenian Army could continue to be a security guarantor for Artsakh, or they thought that only Russians can or should conduct peacekeeping in Artsakh. After the war, most Armenians realized it will take time to restore and reform the army, and it will be difficult for the armed forces to confront the army of Azerbaijan with the latter receiving direct military support from Turkey. The opinions are divided among the parties running in the election on whether Russia will be willing to stay in Artsakh after the five-year term indicated in the tripartite cease-fire statement of November 9, 2020, and whether they should continue to carry out the peacekeeping role in Artsakh alone, based on it, or whether there is a need for an international peacekeeping force under the mandate of the UN or the OSCE to complement or replace the Russian peacekeepers.

After the shocking defeat in the war, the use of the notion of “remedial secession” has not been consistent, neither by the authorities nor by other political forces in Armenia. Arman Grigoryan, a political analyst associated with the Armenian National Congress Party, has said that the doctrine of “remedial secession” is even more applicable after the war than it was before, contradicting his own usually realpolitik approaches. Sheila Paylan and Vrouyr Makalian once more referred to the interrelated principles of responsibility to protect and remedial secession or recognition.

Pashinyan referred to “remedial secession” again in April 2021, during a meeting with Gerard Larcher, the President of the French Senate.

The Bright Armenia Party has taken a different approach, suggesting a solution based on the notion that Artsakh should be unified with Armenia, without specifying the mechanism of that process. The National Democratic Pan-Armenian Axis has noted a number of treaties and declarations from the 20th century that, they argue, constitute a legal basis for claiming that Artsakh has been part of Armenia, and its reunification with Armenia would restore Armenia’s territorial integrity.

Although those forces may think that their notions contradict the principle of remedial rights, it is possible to combine elements of those different approaches and elaborate a comprehensive strategy for overcoming the deadlock over the resolution of the Artsakh conflict. In my opinion, Armenia should prepare a solid legal package and present it to international legal bodies, such as the International Court of Justice, along with lawsuits in other international judicial and quasi-judicial institutions in relation to the violations of international humanitarian and human rights law by Azerbaijan toward Armenians both during the first and second Artsakh wars. Some of this is already underway in the ECtHR. Most importantly, this work should be done in parallel with the resumption of active diplomatic processes under the auspices of the OSCE, with the re-engagement of the U.S. and France. Towards that end, constructive domestic political discourse should be launched, and collaboration of political forces and professional experts should be established, instead of the usual politicization and polarization, and seeking contradictions rather than synergies between different approaches.

The use of the principle of remedial secession seems to remain a possible way out of the dreadful situation created around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Even if the number of civilian casualties hasn’t been high during the 2020 Artsakh War, the violations of international humanitarian law throughout it, the extensive use of Armenophobia and ethnic hatred toward Armenians in the statements of Azerbaijani President Aliyev and other figures in Azerbaijan, tracked by the Human Rights Defenders of Armenia and Artsakh, and apparent existential threat to the Armenians in Artsakh, especially in the event of a withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers in light of the lack of solid legal basis and international mandate of their mission constitute a basis for justifying the applicability of remedial secession.

Armenia Votes: Party and Alliance Programs

Armenian citizens are preparing to head to the polls on June 20, 2021, in an early parliamentary election. A record number of political forces are taking part in this highly contested and polarized election. Although there is only one week before Election Day, not all of the parties have published their election programs. Taking into consideration the post-war situation, the polarization of society, the tense campaign period and the large number of undecided voters, EVN Report has translated and compiled certain thematic sections of the programs [foreign relations, defense and security, economy, education and healthcare] of seven of those political forces in order of their position on the ballot. They include: the Armenian National Congress, Civil Contract Party, I’m Honored Alliance, Bright Armenia Party, Prosperous Armenia Party, Citizen’s Decision Party and Armenia Alliance.

also see

Armenia’s June 2021 Parliamentary Election: The Essential Primer

By Lusine Sargsyan , Harout Manougian

Twenty-six political parties and alliances of parties have registered with the Central Electoral Commission to take part in the upcoming snap parliamentary election in Armenia. Everything you need to know about them is in this essential primer.

Magazine Issue N7/ Political Culture

EVN Report’s May issue, entitled “Political Culture,” looks back on the evolution of democratic expression in Armenia, from the first parliamentary election in 1919 to political cartoons to the modern day.

See the Magazine Issue here.

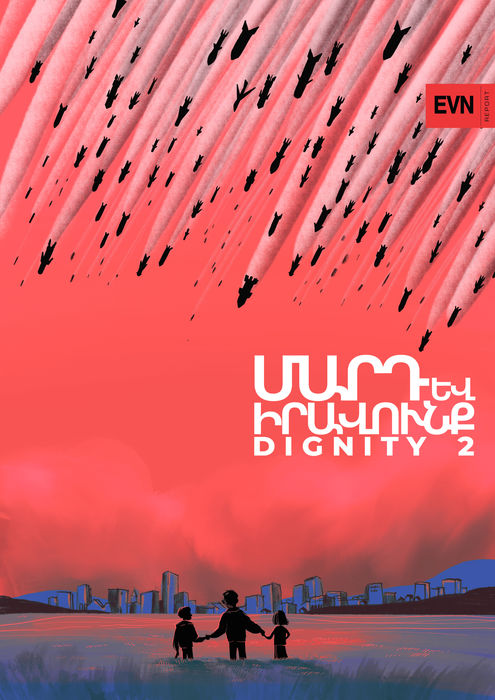

Magazine Issue N2 / Dignity

The imperative to protect human rights must be a daily endeavor for all - for those in positions of power and for ordinary citizens. Protecting human rights must include daily acts of courage and resilience, not only during times of war, but also in peacetime. EVN Report's December, 2020, issue “Dignity” is dedicated to those rights for all.

See the Magazine Issue here.