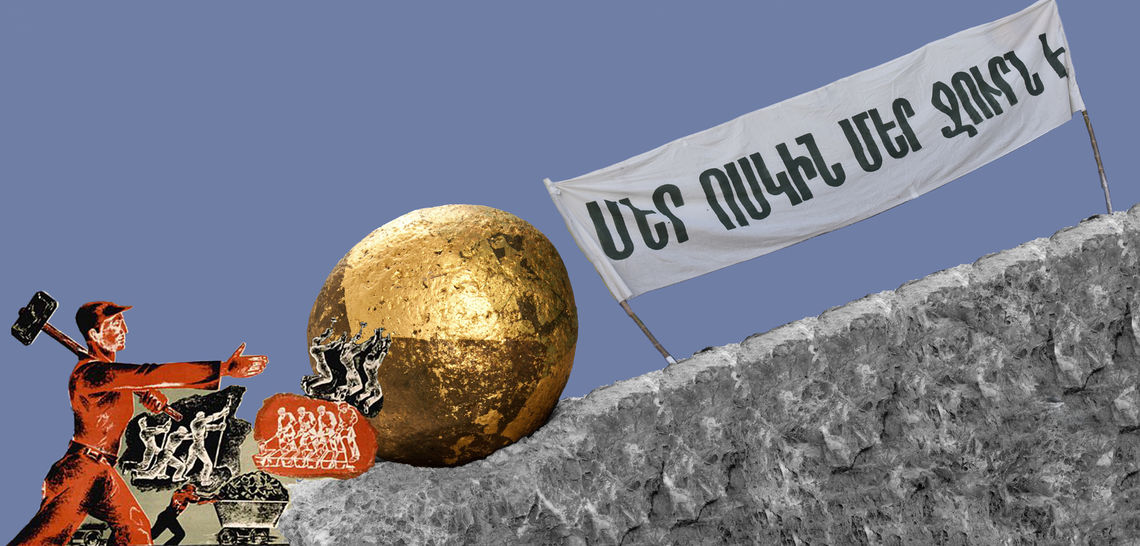

Banner : "Water is our gold."

Mount Amulsar, almost 3,000 meters above sea level, is located near the resort town of Jermuk and the major rivers Arpa and Vorotan. For the past several years, the mountain has been under the spotlight of environmental activists. An estimated 70 tons of gold are expected to be extracted from Amulsar over a 10-year period. It has relatively low grade of gold at 0.78 grams per ton of ore. In comparison, the gold mine at Sotk, some 20 kilometers off the southeastern coast of Lake Sevan, contains 120 tons of gold at 5-7 grams of gold per ton of ore. An offshore company called Lydian Armenia was given final permit by the Ministry of Nature Protection to start construction at Amulsar in 2014.

The project has been highly controversial. Environmental activists claim it will cause severe damage to Armenia’s nature, especially its waters, including Lake Sevan. The most consequential problem with mining at Amulsar is the probability of an acid mine drainage into the Arpa River and the Kechut reservoir, built on the Arpa. It is connected to Lake Sevan with a 49 kilometer long tunnel built in the Soviet period to halt the unsustainable outflow of the lake’s waters exploited at a heavy pace for hydropower and irrigation.

The second issue is the use of cyanide in extracting the gold from the ore in a process called heap leaching (a mineral processing and extraction technology). Besides the legality of use of cyanide, environmentalists point to its close proximity to residential buildings in the village of Gndevaz. The heap leaching, now under construction, is only a kilometer away. Cyanide may even travel to as far as 30 kilometers from the site with the dust causing serious health problems for humans, but also damaging plants and animals. Lydian representatives either deny or minimize these concerns.

According to Armen Stepanyan, Lydian Armenia’s Sustainability Director, water drainage and control systems will protect any damage to the Kechut reservoir from acid drainage, particularly from the barren rock storage facility. David Tyler, the company’s Mine Technical Manager, says Lydian Armenia will also take measures to rehabilitate the area after mining is complete. In a five-year process, the open pits will be partially backfilled, the Heap Leach Facility will be “cleansed, covered with rocks and topsoil for rehabilitation and revegetation.” The company claims the same will be done with the barren rock storage facility. “All unnecessary infrastructure and buildings will be dismantled and removed if not wanted by the community, and the land will be fully reclaimed and revegetated enabling the land to return to its pre-mining use,” Tyler says.

Old Regime, New Government

Following the resignation of Serzh Sargsyan and rise to power of protest movement leader Nikol Pashinyan, finding a solution to mining at Amulsar has become more relevant than ever. Activists (both local residents and those from Yerevan and elsewhere) feel more emboldened than ever. They feel as if they can influence this government, which has the trust of the majority of Armenia’s population.

On June 6, First Deputy Prime Minister Ararat Mirzoyan, met with activists and residents opposed to the mine. A task force was set up to examine the project. In a turn of events surprising for many activists, Pashinyan called for activists to halt blocking roads leading to the construction site. He also labelled civil disobedience there an act of “sabotage” against his government. He urged activists and those concerned with mining at Amulsar to give his government time to adequately examine the issue. Activists deny working against the revolutionary government. They believe that if construction resumes at Amulsar, Lydian may cross the point of no return and the new government, which they admittedly do not distrust, will be powerless to fix the problem.

On July 1, 2018 a group of around 100 activists from Yerevan visited the province of Vayots Dzor to raise awareness among the public about mining at Amulsar and its potential dangers. Stopping at the village Areni and the cities of Yeghegnadzor and Vayk, they passed out leaflets and talked to people one-on-one about the issue.

Gevorg Safaryan, an activist recently released from jail where he served just over two years on politically motivated charges, was among the group of activists. “The mine at Amulsar is a bomb planted under Armenia’s water resources, including drinking water. It can pollute not only the underground mineral waters of Jermuk, but also Lake Sevan, the largest resource of freshwater in the region,” he said. “It is a strategic danger for the Republic of Armenia.” Safaryan urged the government of Nikol Pashinyan to temporarily halt any construction at Amulsar until the task force reaches a conclusion. Recently, Ashot Arsenyan, an MP and a businessman who owns Jermuk Group, famous for the Jermuk mineral water, resigned from the former ruling Republican Party. He cited his membership to the party as a problem in solving the standoff over Amulsar.

Armenia’s current president, Armen Sarkissian, as well as Prince Charles of Wales, Russian-based Armenian businessman Ruben Vardanyan (as the founder of Ameriabank) have been implicated in having some role in implementation of mining at Amulsar, or having supported it. Sarkissian was, in fact, appointed to the board of directors of Lydian International in 2013. Anna Shahnazaryan, an environmentalist from the Armenian Ecological Front, argues that there was strong international pressure on the Armenian government to allow mining at Amulsar. The pressure continues on the current government as well, she believes, especially from the UK and U.S. governments.

Vazgen Galstyan, an activist from Jermuk and president of the Jermuk Development Center, a local NGO is one of the several dozen people who have been blocking the roads leading to Amulsar. Galstyan claims all construction should be permanently shut down as mining at Amulsar violates public interest.

related

State Governance Failures in Mining and Lessons for Armenia’s Future

By Alen Amirkhanian

In his first piece for EVN Report. Alen Amirkhanian writes about the current state of the mining industry in Armenia. He argues that mining governance, from decision-making process on granting mining licenses, monitoring performance to ensuring compliance with laws and standards, is defective and in need of determined reform.

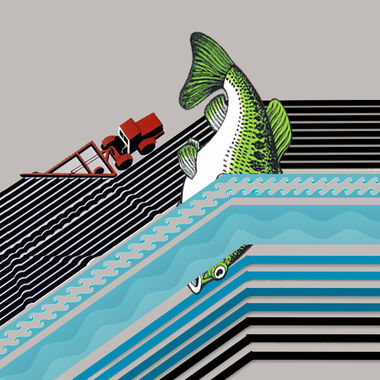

Trying to Fill a Bottomless Well: Depletion of Water Resources in the Ararat Valley

By Gohar Stepanyan

Fish farms that showed up in the Ararat Valley in the early 2000s, as part of a development and poverty reduction program, have devastated the valley and Armenia’s second largest water basin. Now the state is trying to salvage the main hub of Armenia's agriculture and the strategically important water basin from desertification; trying to refill a bottomless well drop by drop.