Sat Nov 25 2017 · 9 min read

Trying to Fill a Bottomless Well: Depletion of Water Resources in the Ararat Valley

By Gohar Stepanyan

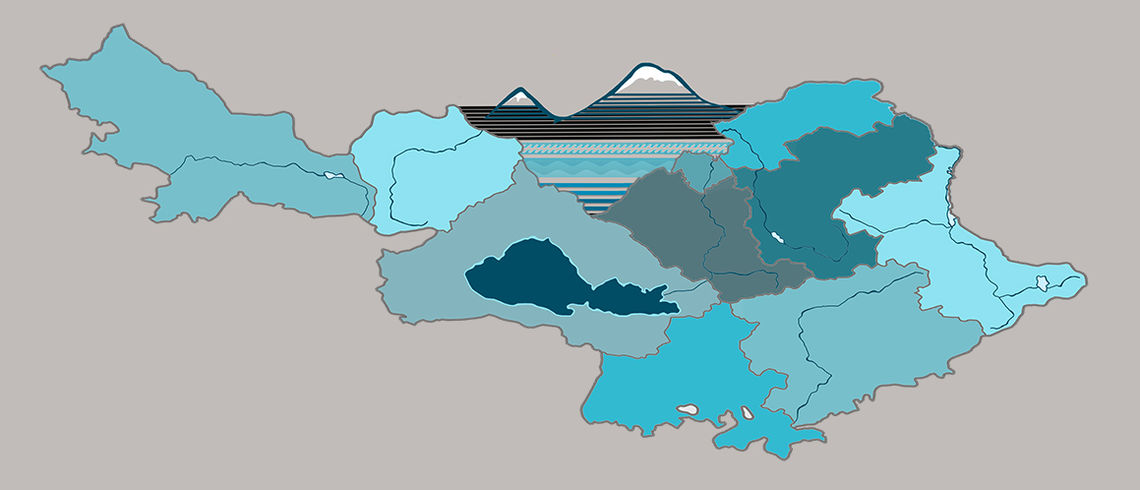

The Ararat Valley is the backbone of Armenia's agriculture, accounting for approximately 40 percent of the country’s agricultural production. Situated 800-1000 meters above sea level, it is thanks to the existence of underground water reserves that the area is not a desert but a fertile agricultural region. However, fish farms that emerged in the early 2000s (as many as 235 at one point, currently 135), have brought the valley to the brink of disaster by partially or mostly depriving arable lands and vegetable gardens of water for irrigation.

The volume of groundwater being abstracted in the Ararat Valley continues to exceed sustainable rates. In 2013, groundwater abstraction hit record levels, rising to 1.7 billion cubic meters, 65 percent of which was used for fish farming. Recognizing that the overuse of water by fisheries in the valley had created a crisis situation, attempts were made by Armenia’s government to implement some oversight and regulations, including stricter regulation over water use and permit-enforcing processes and adjustments to the abstraction fees.

Vahan Davtyan, Head of the Water Resources Management Agency of Armenia’s Ministry of Nature Protection said, “Levels of underground water reserves in the Ararat Valley are stabilizing.” According to Davtyan, the most critical period for underground water reserves was in 2013, but since 2016, the situation has stabilized, and in certain areas the water level has even risen.

While Davtyan insists that the situation has stabilized, in 2016 alone, 1.6 billion cubic meters of water was abstracted, 809 million cubic meters of which was used for fish farming.

Clearly, the situation remains critical.

The Soviet Armenia State Committee on Reserves limited water abstraction from the Ararat aquifer basin to 1.09 billion cubic meters back in 1984. This was enacted into law in 2015 through the Law on the National Water Program. But in 2013, the registered water abstraction from the basin exceeded the set quota by 1.8 million cubic meters, exceeding the permitted volume by 1.6 times in the Ararat region and by 4.5 times in the Masis region.

After Lake Sevan, the Ararat Valley artesian basin is the second largest freshwater reserve in the Republic of Armenia and is of strategic significance. Because of overexploitation of the underground basin by the fish farms, the artesian surface area has decreased by 30 percent and groundwater levels have gone down by 0.5 to 15 meters, depriving 31 communities of self-emission wells that were used for irrigation and drinking water.

According to a 2013 USAID financed study, because of overexploitation of the underground basin by the fish farms, the artesian surface area has decreased by 30 percent and groundwater levels have gone down by 0.5 to 15 meters. The study has also revealed that as a result of decreasing underground water levels, the demand for irrigation water has gone up by 25 percent, leaving the region in need for alternative irrigation water and depriving 31 communities of self-emission wells that were used for irrigation and drinking water. Consequently, water yields of self-emission wells have gone down because of the receding water and the valley is showing signs of desertification, a concern professionals in the field have been voicing for years.

Indeed, depletion of the underground artisanal water has led to a loss of soil moisture, resulting in an increased need for irrigation water and lower soil fertility.

“Our water situation has been problematic since 2005. The water levels dropped and we had to dig an extra seven meters. At this rate, we will have build a tunnel to bring the water out,” Hasmik from Mrkavet village in the Ararat region said. “Now we get water from a depth of 17 meters.” Hasmik said that it now takes them two days to irrigate their greenhouse, row by row, turning the water on and off, whereas before they used to be able to water the greenhouse in half an hour.

According to Hasmik, in 2012, they had to deepen the well yet again by an extra two meters but the water flow is still very slow. “The flow is a little better in the fall but even then there are people who don’t get water and some hardly reach it at a depth of 22 meters,” she explained.

After Lake Sevan, the Ararat Valley artesian basin is the second largest freshwater reserve in the Republic of Armenia and is of strategic significance. Some of the natural springs in the valley supply water for the cooling system at Armenia’s Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, which provides almost a third of the electricity supply to the country.

In 2014, (and again in 2017) Armenia’s government authorized the release of water from Lake Sevan, exceeding the maximum annually allowed volume to replace the deficit of irrigation water in Ararat. In 2016, the government also initiated a large scale World Bank financed program to divert water from the Azat dam to irrigate the Ararat region, a project that would have deprived communities in the Garni region of the Kotayk province of their own water source. The program also threatened to devastate the nature of the Azat River gorge by replacing the river with pipes thereby harming the ecological makeup of the river that passes through the Khosrov State Reserve.

According to the World Bank, the project planned to “construct an intake structure on the Azat River 9 km upstream from the Azat reservoir. It would also construct a 23.5 km pipeline to take water to the current discharge basin of the Kaghtsrashen pump station to enable gravity irrigation for the land covered by the existing system” which eventually reaches the Ararat Valley.

This initiative, however, faced fierce resistance from the local communities and came to a halt.

Water from Fish Farms

Currently, the Ministry of Nature Protection has established a number of working groups tasked with addressing the negative environmental pressure of aquaculture facilities by discharging water from the fish farms in the Ararat Valley back into agricultural lands using pumps or gravity flow. According to the Minister of Nature Protection, Artsvik Minasyan, the use of water discharged from the fish farms in agriculture will provide communities with irrigation water. It will also lighten the load on the Sevan basin.

This year, through the USAID Advanced Science and Partnerships for Integrated Resource Development, ASPIRED project, adjacent areas of the Hayanist community in the Ararat region were irrigated using water pumped from a nearby fish farm. For the first time, 82 farmers were able to cultivate about 40 hectares of previously non-irrigated land. A new pumping station at the water discharge point of the fishery was built and quality analysis of the water was conducted to ensure it met the necessary quality standards for irrigation.

Hayk Petrosyan, an engineer with the ASPIRED project said, “This year, the Hayanist community was able to plow and sow the land they were unable to cultivate before. The quality of the water and the taste of the produce have been tested; they comply with the standards,” Petrosyan said.

Taron Temuryan, a resident of the Hayanist community, irrigated his two hectares of land with this water. He grew okra, tomato, eggplant, melon, watermelon, and says he is satisfied with the harvest.

And though people in Armenia often complain that agricultural products taste of fish, Artsvik Minasyan, Minister of Nature Protection, denies the fact that produce irrigated with water from fisheries can taste of fish since the ministry has piloted the project just this year.

Taron Temuryan also insists that there is no fish taste whatsoever and the vegetables have preserved their flavors. “There is no other water source in the village, this is it, we can not count on rainwater to cultivate our lands. I’m satisfied with this water, the pressure is good, there is no difference,” Temuryan said. “It is the same irrigation water and irrigation in Armenia is generally terrible.”

Wells dug for fish farming have intentionally been made larger; exceeding the sustainable rate by over 45 percent. The required 500 meter distance between wells has not been respected.

As a result, the natural connection between water from confined and unconfined aquifers has been disrupted, changing the chemical makeup of the basin and large cracks have appeared on the land and on the walls of residential buildings.

Fisheries Forced to Comply?

Twenty electronic water meters were recently installed at four of the largest fish farms in the Ararat region. “The electronic water meters will transmit data to the central headquarters which will be located at the Ministry of Nature Protection,” Minasyan said and added that after some time, even citizens will be able to follow the levels of underground water reserves.

According to the Minster, the joint electronic system will help economize water used from the underground reserves and avoid corruption risks.

Following the 2013 USAID study, over 100 abandoned wells were temporarily sealed or permanently closed off, which helped stabilize the situation because there was significant loss of water. However, water meters on remaining wells are either out of order or wells are not equipped at all. Therefore, the aim of the project which was to be able to clearly verify the volume of water used by fisheries and detect whether this volume affects underground water resources continues to remain an issue.

Arman Mkhoyan, owner of Golden Fish LLC located in the Ararat valley insists that they have been able to economize their water usage by 30 percent. “The allowed water usage limit for this fish farm in 2100 liters/minute, but we have brought the usage down to 1500 liters/minute,” Mkhoyan said.

Among other measures, the fishery has also installed electric water meters. Golden Fish abstracts water from a depth of 180 meters and by employing new technologies and enriching the water with oxygen, hopes to use the water more than once before diverting it to be used in agriculture.

Crisis Mode

Usually, the fish farms take the water from a depth of 200 meters or deeper, using self-emission wells, which means they don’t have to use electricity to pump the water, it automatically fountains to the surface. This is different from the water abstracted for irrigation, which is taken from a depth of 30 meters; here the water is not pressurized and the farmers use pumps for their wells connected to electric meters.

A monitoring by specialists has shown that wells dug for fish farming have intentionally been made larger resulting in significant overuse; exceeding the sustainable rate by over 45 percent. Aside from this, the required distance between wells - 500 meters - set by law has not been respected. As a result, the natural connection between water from confined and unconfined aquifers has been disrupted, allowing the waters to mix thereby changing the chemical makeup of the basin. (Unconfined aquifers are those into which water seeps from the ground surface directly above the aquifer. Confined aquifers are those in which an impermeable rock layer exists that prevents water from seeping into the aquifer from the ground surface located directly above).

This has affected more than just the structure of the water basin. The Masis municipality has received 11 complaints from residents that cracks have appeared on the walls of their houses threatening the stability of the structures. Large cracks have also appeared on the land, a phenomenon that still continues in the Masis region and its adjacent territories.

Final Thoughts

Currently water abstraction in the Ararat Valley is about 1.67 billion cubic meters/year while according to the law on the National Water Project, the renewable underground water resources of the Ararat Valley should not exceed 1.1 billion cubic meters/year.

The permissible water abstraction limit of Ararat Valley was set back in 1984, however this limit was clearly exceeded when water usage permits were granted to fish farmers by the Minister of Nature Protection, led by then Minister Aram Harutyunyan, who later was appointed Chairman of the State Committee on Water Economy in 2015 by then Prime Minister Hovik Abrahamyan.

The decision to include fish production in the list of priority areas of development and poverty reduction programs in Armenia in the early 2000s has devastated the valley and the water basin. Now they are trying to salvage the fields from desertification and the disaster of water depletion; trying to refill a bottomless well drop by drop.

related

Global Pressures or Lack of Vision? Armenia in GMO Limbo

By EVN Report

Today, the demand for increased agricultural productivity to ensure food security, the use of genetically engineered crops and powerful conglomerates that control most of the world’s seed industry like Monsanto are threatening the lives and livelihoods of small farmers all over the world. This contentious global debate has now found its way to Armenia. EVN Report investigates.