Tue Nov 14 2017 · 20 min read

Global Pressures or Lack of Vision? Armenia in GMO Limbo

By EVN Report

Members of the EVN Report editorial team discuss two of the most recent developments in Armenia - GMOs and the state of agriculture in Armenia, student protests and the new military law.

The ancient practice of farmers saving seeds from one season to another is slowly being obliterated. Today, a handful of powerful conglomerates in the business of manufacturing and selling GMO (genetically modified organisms) seeds are slowly taking control of the world’s food supply. And they have a growing number of voices within the international community on their side.

We keep hearing about the critical need to ensure food security in the face of a global population explosion. Increased productivity in agriculture thanks to genetically modified crops is being touted as the only viable solution to ensure food security and that countries, regardless of their size and capabilities, can no longer be immune to that trend.

While food security means having access to safe, sufficient and nutritious food to meet the dietary needs and preferences of communities, the rights of farmers and even governments are being violated. We are being asked to believe that genetically engineered seeds and chemical-intensive industrial farming methods are productive and profitable for farmers. What about the environmental impact of these techniques? What happens to indigenous varieties and plant diversity? What about the rights of farmers? Could sustainable organic farming practices be productive and profitable?

There are voices on both sides of this fierce and contentious global debate that has now found its way to Armenia.

What Caused the Uproar?

On November 1, a business forum organized by the U.S. Embassy in Armenia, in partnership with the Ministry of Agriculture and HSBC took place in Yerevan. The stated objective of the forum was meant to strengthen commercial ties between American and Armenian agribusinesses. When it became clear that one of the companies at the forum was Monsanto, a wave of online protests flooded social media platforms.

The U.S. Embassy was quick to respond to concerns and told news.am that two American companies, Valmont and Monsanto had sent representatives to the conference to present their products and services. They also said that Monsanto products had been available in the Armenian agrimarket since 2006 and it was up to Armenia’s farmers to decide which products and services to use, if any.

It remains unclear how Armenia’s farmers, many of whom are involved in subsistence farming will be able to make informed decisions or protect themselves from large multinational conglomerates who control the global seed industry. But more on that later.

When asked further about the situation, a U.S. Embassy official told EVN Report: “Our role was to provide a forum for U.S. and Armenian agribusinesses to meet. We are not pushing any particular agribusiness in Armenia, and as we've said, the decision on which products and services Armenian farmers will use, if any, is ultimately up to them. It is also up to the Armenian government to appropriately regulate the market to ensure the safety of Armenia’s agricultural sector, in accordance with its obligations as a member of the World Trade Organization."

What We Know or Don’t Know

Aside from the known/unknown side effects of GMOs and the serious concerns it raises, it was the name Monsanto that raised many red flags. The United States and Monsanto dominate the global market for genetically engineered crops. Additionally, 80 percent of the genetically modified corn market and 93 percent of the genetically modified soy market in the U.S. is controlled by Monsanto. The company not only dominates America’s food chain with its GMOs, it is known for its ruthless legal battles against small farmers and toxic contamination with its herbicide Roundup which contains glyphosate.

While people were up in arms about a representative of Monsanto taking part in the forum and about the possibility that GMO seeds had been imported to Armenia, the fact that Monsanto products had been available since 2006, took many by surprise including us at EVN Report.

After conducting intensive research, speaking with officials from relevant ministries, specialists in agribusiness, representatives and distributors of Monsanto products and others, there are more questions than answers.

When we decided to take on the gargantuan task of wading into the realm of genetically engineered crops, we discovered a treasure trove of media reports and studies about GMOs in Armenia since the late 1990s. No one paid attention. Neither did we.

What we know now and perhaps shouldn’t be surprised by is that regulations in the sector are either non-existent or weak; where there are clear laws, they are not being implemented; serious infractions are being swept under the rug either due to lack of knowledge (and by knowledge we mean robust statistics) or incompetence; and data about the percentage of GMO or hybrid seeds being used in farming are almost impossible to determine.

Almost everyone we spoke to agreed or acknowledged that there are GMOs in Armenia and when they do exist they must be labeled, yet no one has seen a label on any fruit or vegetable. We’re not even sure which companies are importing GMOs and to what extent, neither do the relevant authorities. And what about indigenous crops? Consumers are hard-pressed to find heirloom Lia or Anahit varieties of tomatoes these days in urban supermarkets unless they go out into the villages.

Gagik Sardaryan, director of the Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development asked the most important question - what is our vision and purpose for the country? “If we want thousands of prosperous farmers producing enough good, healthy food and feeding the population, that’s one policy,” he said. “But if we want to depend on imports and feed people in other countries and make a couple of food importers extremely rich, then this is a different ‘policy’ that has nothing to do with national interests.”

Now that these facts have become public knowledge, the imperative lies with Armenia’s government to ensure proper regulation and oversight, to design strategies and programs to assist the already fragile agricultural sector of the country and safeguard farmers from larger global pressures and finally to have vision and purpose.

A greater imperative lies with the rest of us to hold authorities to account and remind them that their role as public servants means to serve the citizens of Armenia, from farmers to consumers.

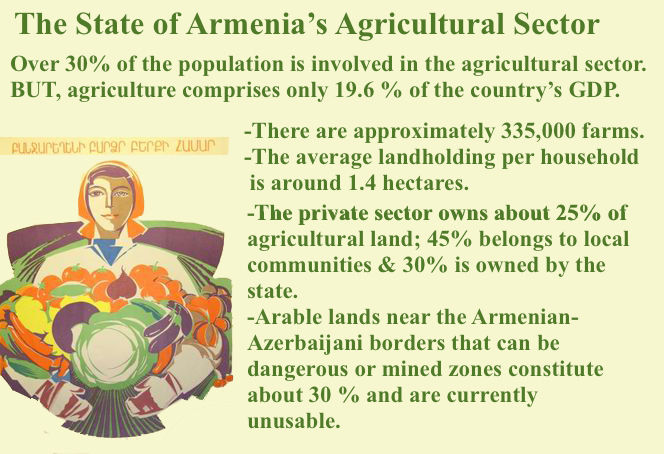

The low productivity, inefficiency and absence of a proper infrastructure has put much strain on the sector. According to FAO, the agricultural sector “is composed of a majority of practically subsistence small farms with small and fragmented plots mainly utilized for subsistence agriculture.”

This does not allow for an efficient and diversified production system, involving both crops and livestock.

There are limited links to markets, limited resources and not much potential for growth unless these issues are addressed. Policy improvements, better regulation, better management of agricultural statistics, and creation of effective farming cooperatives/producer groups need to be implemented to breathe new life into the sector.

Current Situation of GMOs in Armenia

To determine the presence of GMOs in Armenia, we decided to start at the beginning.

Agroline Limited is the local distributor of Monsanto seeds in Armenia. Haykanush Yenokyan, the director of the company told EVN Report that they are the exclusive distributor of Seminis and De Ruiter Seeds, both Dutch-based companies bought out by Monsanto in 2005. Yenokyan said that Agroline has been working with these two companies since 1998 and that their seeds are not GMOs, but rather developed through cross-breeding (hybrid).

Monsanto paid $850 million for De Ruiter Seeds and $1.4 billion for Seminis. However, in 1997, Monsanto purchased the Asgrow Seed Company from Seminis who retained Asgrow Seed Company’s vegetable seed business.

“We only import seeds and they are not GMO,” Yenokyan said, adding that their company does not buy herbicides or pesticides from Monsanto. They receive the seeds for several varieties of vegetables and some fruits (watermelon and cantaloupe) from the Russian distributor of Monsanto. “They [the seeds] arrive with a certificate, but they are not analyzed here by Armenian authorities,” she said. Yenokyan told EVN Report that over 90 percent of Armenian farmers use hybrid seeds.

Maria Maslova, Monsanto’s Corporate Engagement Lead in Russia also told EVN Report that the company does not sell GMO seeds in Armenia or Russia. “I can tell you that we don’t supply GMOs to CIS countries, they are not allowed in Russia, Eastern Europe,” she said. “The market for select hybrid seeds is huge.” She said that both De Ruiter and Seminis were interested in Armenia and farmers in the country wanted their seeds. “It’s nothing like what they say in the news that Monsanto is trying to find a way to get into the Eurasian Economic Union,” she added.

When asked if they imported Monsanto pesticides, Maslova said she was not sure and would advise if this was the case. At time of this publication, EVN Report has not yet received an answer.

Russia has banned the cultivation and breeding of genetically engineered crops, however it doesn’t outright ban imports of them if they are already approved. The decision to ban GMOs was made in 2015 and a year later the Russian State Duma passed a bill formalizing the decision. Nonetheless, under the new law, the government can ban GMO imports to the country if they are “proven to have a negative impact on human health or the environment.”

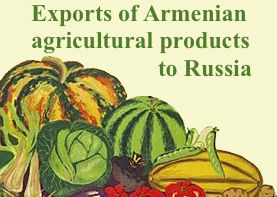

According to the Custom Service of the Republic of Armenia, agricultural goods exported to Russia for the first half of 2017 include a variety of fruits and vegetables. If it is found that GMO crops are being grown in Armenia, this could also compromise Armenian exports to the European Union.

Vegetables Potatoes, 170.5 tons Tomatoes, 18455.3 tons Onions, 3.9 tons Cabbage, 292.9 tons Carrots, 706.4 tons Cucumbers, 392.4 tons Beans, different types, 1.3 tons Other types of vegetables, 58.3 tons

Fruits

Melon, watermelon, 193.3 tons

Apple, pear, quince, 285.3 tons

Apricot, cherry, peach, 1586.4 tons

Source

GMO Regulation in Armenia

Unlike Russia and many other countries, Armenia does not have a law banning the cultivation or import of GMOs. Approximately 40 countries around the world ban GMOs. The EU lifted a five-year moratorium on GMO imports in 2015 but allowed EU member states to restrict or ban the cultivation of crops containing GMOs on their territory. However, all 28 EU member countries require GMO labeling.

While Armenian law does not ban GMOs, any product containing them must be labeled. According to the State Service for Food Safety of Armenia’s Ministry of Agriculture, any genetically modified food in the country must be labeled in the Armenian language and contain information about the genetically modified component.

The following three types of food are considered as genetically modified products according to the agency:

- "Food, which is received as a result of the transformation of genetic structure with foreign gene inserting or gene combinations in living organisms (animals, plants, microorganisms) for the purpose of receiving other qualitative properties,

- Food, which is received as a result of biological activities of living modified organisms,

- Food which is received as a result of transformation of the genetic structure in food composition and (or) the product received as a result of biological activities of living modified organisms and (or) the utilization of their individual parts."

Deputy Minister of Agriculture, Ashot Harutyunyan told EVN Report that according to Article 9 of the RA Law on Food Safety, if there is data of the presence of components derived from genetically modified organisms in food of more than 0.9 percent, it must be clearly labeled and in the Armenian language. Harutyunyan was also quick to mention that Armenia has signed the Cartagena Protocol on Biodiversity, the objective of which “is to contribute to ensuring an adequate level of protection in the field of the safe transfer, handling and use of living modified organisms resulting from modern biotechnology that may have adverse effects on the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health, and specifically focusing on transboundary movements."

The government’s Armenia Development Strategy for 2014-2025 (Government Decree #422-N, March 27, 2014) considers agriculture one of the key areas of economic growth. However, marketing of agricultural products continues to be an impediment as there are “a lack of agencies responsible for marketing of agricultural products or their ineffective activities.” Today, over 90% of agricultural machinery in the country is outdated resulting in high maintenance costs and low productivity.

The Deputy Minister also stressed the precautionary principle contained within numerous provisions of the Protocol. “Any signatory to Cartagena can refuse to import GMOs,” he said.

The precautionary principle is a relatively new concept in international environmental law. It basically advocates precaution where scientific uncertainty exists. The objective is to “anticipate and avoid environmental damage before it occurs.”

Erring on the side of caution, Harutyunyan could not definitively say if GMOs were being imported to Armenia. “If someone puts GMO seeds in their pocket or luggage and brings them to Armenia, we wouldn’t be able to know,” he said.

Gagik Manucharyan, head of the Environmental Protection Policy Department of the Ministry of Nature Protection echoed these sentiments. “Armenia is still not able to prove if a given food that enters the country contains GMOs or not,” he said. “If I’m not mistaken, there is only one lab, Standard Dialog, that claims to be able to do GMO testing and analysis.” The lab was founded in 2009 and states that they have been testing for GMO presence in foodstuff since 2010.

Currently, Armenia does not have the capability of analyzing seeds - whether they are GMO, hybrid or elite seeds - coming into the country from different border crossings. “If we want to have state labs that can accurately test for GMOs, it would cost us close to $100 million,” Manucharyan said. “We can’t have just one lab and bring samples from all over the country to that one location. We would need divisions on every border crossing.” Alternatively Manucharyan said that if all seeds were to be sent to one location, then the state would have to compensate for damage done to any product that gets stranded at the border and is not a GMO.

The Deputy Minister of Agriculture Ashot Harutyunyan told EVN Report that the Law on Seeds will be amended to ensure that a mechanism is put into place to ensure that seeds coming into Armenia will be analyzed. However, who or how this will be funded remains unclear.

Harutyunyan admitted that the core of the problems started earlier. “Several years ago, there was a directive to liberalize the seed market through amendments to the Law on Seeds and this is where the problems began,” he said. According to the deputy minister, this relaxing of the laws or de-regulation was meant to encourage agribusiness. “Now that we are in a situation where biosafety and security are issues, we will be implementing stricter regulations to ensure that any seed coming into the country is registered and analyzed,” he explained.

Putting aside the issue of seed analysis, the answer to whether GMO seeds are being cultivated on Armenian farms remains moot.

The Development Strategy acknowledges the need for developing an effective food safety system, which should include:

- “Improvement of regulations regarding genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the respective legislation to ensure absence of threat to human life and health, animals and biodiversity, as well as protect consumer rights.

- “Development and implementation of monitoring programs for control over remainings of pesticides, hazardous organisms, veterinary remainings, allergenics, food additives and GMOs in imported and locally produced food.”

The director of the Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development (CARD) Gagik Sardaryan thinks there might be GMOs in Armenia but their use is not widespread. “Just as we cannot avoid the Internet, we can also not avoid GMOs,” he said. “That is the global trend.” Sardaryan believes that concerns about Monsanto’s presence in Armenia are misplaced. “We are not India, we are not Pakistan or the EU,” he explained. “We are a small country with a very small market and GMOs are utilized mostly for large plots of land and heavy agriculture.”

Manucharyan on the other hand, didn’t mince words. “There are GMOs in the country,” he said. “I can tell you for certain that seeds for soy, corn, tomatoes and different varieties of potatoes imported to Armenia contain GMOs.”

Dr. Nune Darbinyan, an expert on organic agriculture and certification, founder of Ecoglobe organic certification and President of Eco-Globe NGO says that GMOs are present in the market. “Farmers often have no idea regarding the name of the seed varieties they buy,” Darbinyan said. “They simply know who gave them the seeds or where they have been purchased.” She also noted that there is no information regarding processed food containing GMO.

There are three institutions that are primarily responsible for food safety in Armenia.

- The State Service for Food Safety (SSFS) within the Ministry of Agriculture, which includes the Phytosanitary Inspectorate and the Food Safety and Quality Control Inspectorate

- The State Health Inspectorate of the Ministry of Health

- The National Institute of Standards of the Ministry of Economy

Several sources mentioned that some of the GMO seeds used in Armenia (specifically cherry tomatoes and hothouse tomatoes) were brought in through UN international donor assistance programs, of which there have been many since independence. EVN Report reached out to the UN office in Yerevan. The response we received from the FAO and UNDP in Armenia is that GMO seeds were never provided to Armenian farmers. A representative of the UNDP said, “I can confirm that we never used GMO seeds; on the contrary, we always mention in our tender documents that they have to be GMO-free and this is mandatory.”

Legislation

A draft Law on the Use of Genetically Modified Organisms and Bio-Safety was put into circulation by the government in 2012 that has yet to be properly vetted by relevant ministries and ratified by parliament. The draft law was meant to establish basic principles and mechanisms for biosafety to eliminate any potential negative impact of GMOs on the environment and biodiversity “Now the Ministry of Nature Protection and the Ministry of Agriculture are making amendments to this bill to determine the jurisdiction of GMOs,” Manucharyan said.

At the time the bill was put into circulation (2012), then Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan held a consultation with senior government representatives. It was decided that amendments were necessary. “The law should contain strict rules in line with the international standards to prevent GMOs from being imported into the Republic of Armenia. The government will call back the bill from the National Assembly in order to finalize it as soon as possible.”

Five years on, the law seems to be in limbo. Clearly, the absence of legal instruments in the country has left farmers at the whim of large corporations dealing in GMO seeds like Monsanto. Gagik Sardaryan of CARD understands this. “It is difficult for a small farmer to identify where the truth is and where, if any, underlying concerns exist,” he explained. “It is the responsibility of the government to educate, train and inform farmers because as it stands, if something is cheaper and promises better results, naturally the farmer is going to go for that.”

Back in May of this year, a draft report prepared by the working group of the Armenian Lawyers’ Association within the framework of “Strengthening Public Oversight and Mechanisms for the Prevention of Corruption in Food Safety Sector” was released. The project manager, lawyer Mariam Zadoyan noted that in terms of legal instruments, Armenia lagged behind. “Almost all countries, even in neighboring Azerbaijan, have a clear position on the use or cultivation of genetically modified organisms,” Zadoyan said. “Whereas our country has no clear position on this issue.” Zadoyan said that this was a major legislative gap and that Armenia has not implemented a number of commitments of the Cartagena Protocol.

Armenia’s inability to have a clear position on GMO cultivation dates back to the early years of independence. Biosafety issues were on the agenda in 1993, when Armenia’s parliament ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity (the Cartagena Protocol adopted in 2000 was a supplementary agreement to this Convention). The First National Report on Biodiversity of Armenia and Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan were prepared in 1999 and addressed the general issues and gaps for developing biodiversity and a biosafety framework and public awareness. These issues were addressed again in a 2004 report released by the Ministry of Nature Protection in cooperation with the United Nations Environment Program and Global Environment Facility called the National Biosafety Framework for Armenia.

Hybrid Seeds in Armenia’s Farmlands

Putting the GMO debate aside for the moment, another concern that surfaced in the course of this investigation is the import of so-called hybrid seeds. These kinds of seeds are developed through specific controlled cross of two parent plants. Plant breeders direct the process to control the outcome, which results in higher yields and heartier fruits or vegetables.

GMOs and Proprietary Rights

Genetically modified technologies are proprietary, developed by the private sector and released for commercial production through licensing agreements. These companies invest billions in research and develop and have patents on their products.

According to a 2003 FAO/WHO expert consultation, intellectual property rights will likely impact on the rights of farmers. The report looks at the technical divide and unbalanced distribution of benefits and risks “between developed and developing countries and the problem often becomes even more acute through the existence of intellectual property rights and patenting that places an advantage on the strongholds of scientific and technological expertise. Such considerations are likely to also affect the debate on GM foods.”

“Hybrid seeds have been cultivated in Armenia for the last 10-15 years and they have been sold in the local market,” Gagik Sardaryan of CARD said. Both Sardaryan and Haykush Yenokyan of Agroline, the local representative of Monsanto, said that over 90 percent of seeds in Armenia are hybrid variety.

This, however, was flatly denied by the Deputy Minister of Agriculture Ashot Harutyunyan. He said that those figures are nowhere near the truth. However, he did admit that potato seeds that are imported primarily from the Netherlands - anywhere from 2000-3000 tons depending on the year - are hybrids. Seeds for grains are local varieties and are not hybrids according to the deputy minister. “Vegetable seeds come in boxes [hybrid seeds], a maximum of five tons annually are imported, that is nothing compared to the entire seed market,” Harutyunyan said.

The challenges and risks with imported hybrid seeds are that they are patented by large corporations that produce them. This means that the farmer can use them for only one growing season, cannot save seed to plant the following season and would have to purchase the seeds every year. This gives patent holders tremendous control over our food supply. With a few exceptions, all contemporary varieties of hybrid seeds developed by private corporations are protected as intellectual property.

Save Nature - Source of Life, Freshness and Health.

Note: For the layout of this article, EVN Report has used a collage of Martiros Sarian's landscapes and vintage Soviet posters promoting agriculture.

Gagik Manucharyan of the Ministry of Nature Protection says that over 90 percent of imported seeds are either hybrid or contain some elements of GMO. And while the law on GMOs is not final or ratified, it seems we have created a whole industry in the absence of such a law. EVN Report asked Manucharyan that moving forward, is it conceivable that any law the country ratifies will have to be adapted to the already existing realities otherwise the current agricultural system could collapse, he said: “If we decide to ban GMOs, half the people will go hungry. We might need to establish an upper threshold for the GMO in our products, something that we might find is not very harmful, but it is up for discussion.”

About the impact that hybrid or GMO seeds could have on heirloom varieties in the country, Manucharyan said that was a question for the Ministry of Agriculture to address. “The farmer has to solve the problem of how to feed his family,” he said. “The farmer who was able to get a yield of 50 kilos from a hectare, opposed to the one who was only able to secure 10 kilos is the smart one, the sound businessman.” Since organic crops or heirloom varieties could potentially be more expensive, “the person on the edge of poverty is definitely going to buy the cheap tomato and is not going to care if it tastes as good as the expensive one.”

“Today, we are not self sufficient because productivity is very low and first of all, in each step, we are missing knowledge and education. The people, the government are willing to invest in everything but knowledge,” Gagik Sardaryan said. “Agriculture is more than just about producing food for Armenia. It is about culture...it is about families and villages and security.”

The time has come for us to get our act together and have a serious discussion. Should Armenia be GMO-free? If yes, laws must be adopted now to ensure they don’t impact, contaminate natural varieties and ultimately livelihoods of farmers. And let’s be honest, with our limited real estate, low productivity, crippling poverty rates, and ineffective, often incompetent bureaucrats, to be globally competitive in agricultural products is unrealistic. Instead, perhaps we have to implement policies to grow and harvest high-value organic fruits and vegetables, thereby creating a niche, a brand for the country.

-------------------------------------------------

Plant Breeding Through History

Plant breeding has been practiced for thousands of years. It can be considered a coevolutionary process between humans and edible plants. People caused changes in the plants that were used for agriculture and, in turn, those new plant types allowed changes in human populations to take place.

There are three ways plants are bred: a) open pollination, b) hybrid cross-pollination, c) direct DNA modification. Farmers have been breeding plants to improve quality, increase yields, increase tolerance to climate change and drought, improve resistance to viruses, insects and herbicides and to ensure the harvested crops can be stored for longer periods of time.

Open pollination occurs naturally. This means that open pollinated seeds are produced from natural, sometimes random pollination by wind, birds or insects. This means that plants are naturally varied. These plants bear seeds that produce plants identical to the parent plant. These plants are genetically diverse and can be more adaptable to local growing conditions. While the first way is through external means (birds, insects, water, wind), the second way is self-pollination, which occurs when the male and female parts are contained in the same plant. Older strains of open pollinated plants are known as heirlooms and they have been saved and passed down through generations. Farmers were able to select and save seeds from the best plants in their orchard to grow them the following season.

Hybrid seeds refer to plant variety developed through specific controlled cross of two parent plants. Plant breeders direct the process to control the outcome. It is possible to cross the genetic materials of two different, but related plants to produce new, desirable traits in the plant. Hybrid plants can be developed to be durable in the face of climate change, be resistant to disease and pests. While open-pollination can take six to ten generations, using the method of controlled genetic crossing, plant breeders can now produce hybrid seeds that combines the desired traits of two pure parent lines in the first generation. The resulting hybrid has higher yields and the fruits are bigger making it desirable for most farmers. With hybridization, a new world of food crops arrived on our tables - from grapefruit to cantaloupes to seedless watermelons.

However, with these innovations control over seeds have shifted from farmers and communities to a few powerful multinational corporations. Most hybrid seeds are patented by the companies that produce them. According to Seminis, one of the companies that sell hybrid seeds in Armenia, they do so to protect their intellectual property rights: “On average, it takes Seminis vegetable breeders between eight to twelve years to develop and commercialize a new seed variety...Obtaining patents and PVP certificates are ways for us to protect our time, ideas and investments spent to develop those products.”

Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) technology requires sophisticated and very expensive lab techniques. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), GMOs are defined as organisms (plant, animals or microorganisms) where the genetic material (DNA) has been altered in ways that does not nor ever could occur in nature. The technology is also called modern biotechnology or gene technology or genetic engineering. “It allows selected individual genes to be transferred from one organism into another, also between non-related species.”

According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the term genetically modified organism means an organism in which the genetic material has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally through fertilization and/or nature recombination. GMOs may be plants, animals or micro-organisms, such as bacteria, parasites and fungi.

According to the Genetic Literacy Project, eighteen million farmers in 28 nations around the world (20 developing; eight industrialized nations) cultivate GMO crops on nearly 182 million hectares. Almost 200 billion hectares have been planted since GMO crops were approved in 1996. GMOs released for commercial agriculture production include (according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO]) but are not limited to pest resistant cotton, maize, canola (mainly Bt or Bacillus thuringiensis), herbicide glyphosate resistant soybean, cotton and viral disease resistant potatoes, papaya and squash.