Tue Sep 24 2019 · 7 min read

A New Governance Architecture for Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture

By Emil Gevorgyan

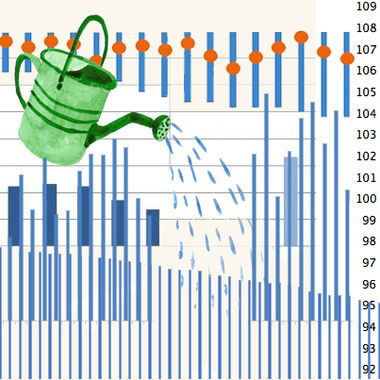

The general direction of agricultural policies in Armenia is to promote high-value, export-oriented crops through industrialization and commercialization as a means to increase overall economic output. After the 2018 Velvet Revolution, the new government declared agriculture, along with tourism and innovative technologies, as a priority area for the country's future development. However, the new policies targeting the agricultural sector do not differ much from the previous ones and fail to meet the needs of the low-income rural population.

The 2018 protests created high expectations for a better future and a more inclusive economy. Applying the hodgepodge of measures in the government's current agricultural strategies for the next decade is likely to lead to disappointment and frustration. The new agricultural strategies of industrialization and commercialization in this sector are neither sustainable nor inclusive; moreover, they fail to meet the real needs and expectations of the people in Armenia. These strategies were not developed in a participatory manner, ignore the lessons of the past and prioritize rapid short-term GDP growth without considering a clear long-term perspective. Without a radical change in our current course and the mindset of decision makers, the implementation of these strategies will serve only a few and exacerbate the poverty of the many.

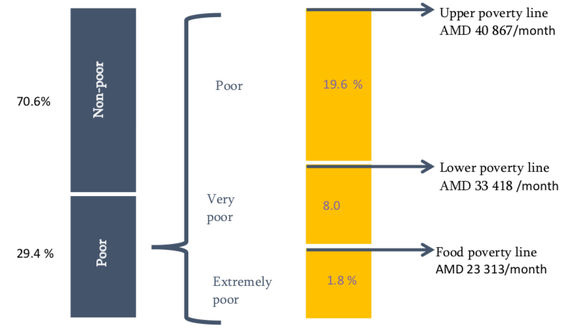

These strategies do not target the low-income rural population affected by the crisis of over-indebtedness due to concerning levels of financial illiteracy and little experience with formal financial services. In 2016, the poverty rate in Armenia was 29.4 percent (with the share of “very poor” at 9.8 percent and “extremely poor” at 1.8 percent) as compared to 27.6 percent recorded in 2008 (Graph 1). There is also a significant difference between poverty rates in urban [1] (28.8 percent) and rural (30.4 percent) communities.

Graph 1. Poverty Rate and Poverty Lines in 2016 in Armenia

According to the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP), 28 percent of Armenian households are at risk of becoming food insecure if affected by shocks; nine percent of children aged under five are stunted due to chronic malnutrition and almost 13.6 percent are overweight. Food security and nutrition go hand-in-hand with sustainable agriculture. In the given situation, the government’s predominant policy paradigms are industrialization, commercialization and export orientation.

A major challenge hindering an improvement in food security is the understanding of the concept of food in the Armenian context. In general, the government’s newly presented strategy describes food as a commodity rather than as a social-ecological system requiring democratic governance in the collective interest. In other words, these policies overlook the social but also environmental dimensions of development and are not sustainable. The negative social and environmental impacts of the government’s ad hoc strategies will be visible in the immediate future. As a result, thousands of traditional farming families engaged in small-scale agricultural activities will disappear and the out-migration, especially of young people, as well as the weakening of rural social structures will continue. The emergence of monocultures and the intensive and uncontrolled use of pesticides and fertilizers will continue to reduce Armenia’s rich biodiversity and change the country’s entire landscape. Intensive animal husbandry and the fish industry have already substantially contributed to nitrate pollution of surface waters as well as surrounding rivers and lakes in the countryside. It is also worth thinking about the substantial contribution to climate change made by industrial agriculture.

It is evident that there is a gap between the government’s commitment to the low-income rural population and the promotion of commercial production focused on well-positioned enterprises and export goods. Moreover, these efforts to expand into new markets primarily target member countries of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), where phytosanitary and food safety standards are still arguably insufficient. Here, we come to the crux of another issue that is extremely important for tailoring targeted policies and strategic measures: who is going to produce for the export markets in an industrial manner and who is today’s Armenian farmer?

The collapse of the Soviet Union and its subsequent contentious privatization process greatly affected the lives of the rural population who were previously engaged in collective farms (kolkhozes). In the frame of a centrally-planned economy, agricultural workers were used to getting clear indications from the central government and its local authorities on what and how to produce. These behavioural patterns have not yet fully adapted to a market economy. Moreover, the structural transformation at the end of the Soviet era and the problematic policies of previous governments have weakened the Armenian economy. In addition, the unequal distribution of access to land and other resources due to the privatization process has resulted in a loss of confidence among the rural population. This loss of trust and related difficult experiences of the past are some of the reasons why people are not willing to cooperate and, for instance, why the law adopted in 2015 on agricultural cooperatives and respective promises of government officials in this regard have not yet been implemented and achieved. This is the case with many laws and regulations targeting the agricultural sector.

The problem also lies in the fact that, by getting several small fragmented pieces of land located quite far from each other (an average of 1.5 hectares per rural family [2]) and having only limited access to knowledge, inputs, transportation, finance and markets, the rural population is obviously not able to act independently, adopt innovations and develop new business ideas for managing their resources and assets. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the rural population was not prepared to withstand the enormous reorganization processes and adapt to the new market economy conditions. The situation was further aggravated by political uncertainties and the lack of social protection mechanisms for the rural population, especially those engaged in the agricultural sector.

In recent years, the agricultural sector has been facing many serious challenges including low levels of mechanization, obsolete irrigation systems and limited availability of quality infrastructure. Rural youth do not perceive agriculture as a business opportunity and prefer working abroad. The poorly-developed or outdated national agricultural extension service has failed in its mission of training the rural population in good agricultural practices and supplying them with information about agricultural innovations. Instead, rural families, youth and agricultural workers of the former collective farms were "unnaturally" reclassified and considered as modern farms, agricultural holdings and farmers in the Western sense of these words. Armenian authorities and their international partners continue to develop policies and implement strategies for 320 to 360 thousand such farms and agricultural holdings.

So who is today’s Armenian farmer in reality? The results of these policies and implemented strategies are sobering. According to UNICEF, every third child in Armenia is currently living in poverty. Recent data from 2017 (34.2 percent child poverty rate, with 2 percent extreme child poverty rate) indicates that there was no reduction in the lowest level of poverty from 2008.

After the 2018 Velvet Revolution, the new government started to optimize the “heavy” state administration system and promised an in-depth reform for the treatment of widespread corruption. In this context, due to the lack of profound strategies and policies for the development of such an important sector as agriculture, it was decided to abolish the Ministry of Agriculture. The re-established Ministry of Economy has been mandated to reform the agricultural sector and develop targeted strategies for thousands of Armenian children currently living in poverty and food insecurity. A system-oriented understanding of how multidimensional challenges can be addressed within the Armenian context is a crucial precondition for achieving the goal of poverty eradication and sustainable development.

Unfortunately, the weak intersectoral cooperation within the government, limited inclusion of qualified personnel and professionals and complex hierarchies impede decision making processes and the implementation of urgent measures for the development of the country. At the same time, funding from public institutions continues to target primarily ambitious ideas of industrialization and commercialization in the agricultural sector and cannot lead to sustained and broad agricultural growth that benefits the poor. Moreover, in the current governance structure, different important segments and authorities are missing or do not fulfill their obligations. Several state project implementation agencies, development funds and parastatal research organizations have been abolished (or are in a tedious liquidation process) in the name of improving governance and tackling system corruption. As an alternative, no new institutions were established to provide services, implement state projects and support political decision making with regard to the development of the agricultural sector.

To sum up, in the aftermath of the 2018 Velvet Revolution, pressing systemic challenges exist on different levels, which cause serious disadvantages, especially for the country’s low-income rural population. In this situation, a common agricultural development policy and immediate institutional changes are needed to put an end to amateurish politics and financial inefficiencies. The common policy and the reform strategies should be developed to bring varying policies into coherence, set common goals over different sectors related to food security and sustainable agriculture and rule out hidden costs, such as those caused by individual preferences of policymakers. In other words, these measures would lead to sustainable and inclusive development in the agricultural sector and bring major benefits and prosperity for all people. This is a call to action for fundamental changes and policies that represent the values of the 2018 protests: leave no one behind and aim at achieving greater equality and strong welfare in Armenia.

-------------------------

1- 24.9 percent in Yerevan

2- NSS: Agricultural Census 2014

read also

Global Pressures or Lack of Vision? Armenia in GMO Limbo

By EVN Report

Today, the demand for increased agricultural productivity to ensure food security, the use of genetically engineered crops and powerful conglomerates that control most of the world’s seed industry like Monsanto are threatening the lives and livelihoods of small farmers all over the world. This contentious global debate has now found its way to Armenia. EVN Report investigates.

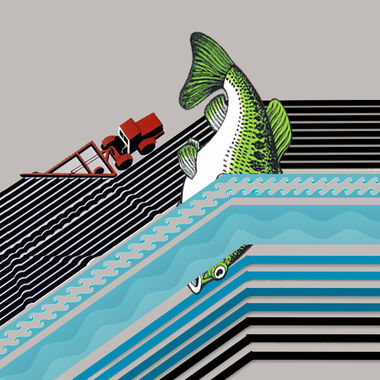

Trying to Fill a Bottomless Well: Depletion of Water Resources in the Ararat Valley

By Gohar Stepanyan

Fish farms that showed up in the Ararat Valley in the early 2000s, as part of a development and poverty reduction program, have devastated the valley and Armenia’s second largest water basin. Now the state is trying to salvage the main hub of Armenia's agriculture and the strategically important water basin from desertification; trying to refill a bottomless well drop by drop.

Economic Revolution or Hopes for a Miracle

By Paruyr Abrahamyan

Can Armenia’s new government deliver on its promise of an economic revolution following the Velvet Revolution of last spring? Paruyr Abrahamyan decodes the promise of that revolution.

We are pleased to open up a comments section. We look forward to hearing from you and wish to remind you to please follow our community guidelines:

EVN Report welcomes comments that contribute to a healthy discussion and spur an informed debate. All comments on Readers' Forum will be moderated, thereby any post that includes hate speech, profanity or personal attacks will not be published.