Wed May 31 2017 · 17 min read

The Families of Sari Tagh

Struggling for Justice

By Maria Titizian , Roubina Margossian

Ten people remain in pre-trial detention following the July 19, 2016 clashes with police in Sari Tagh, Yerevan.

Ten families are srtuggling with Armenia's justice system and to make ends meet.

When we arrive in the neighborhood of Sari Tagh, a boy of about 13 greets us and takes us to see Lala. We walk through a makeshift corrugated fence that has a For Sale sign spray-painted in red. We enter a small courtyard and come upon a decrepit two-storey structure, the first floor of which is unfinished. There are no windows or doors. The stairs leading up to the second floor are cracked and uneven. It takes some delicate maneuvering to climb them.

As we enter through the front door, we find ourselves in a small rectangular room and although the sun is shining brightly outside, it is dark and dank inside. The wallpaper is peeling, there are water stains all over the ceiling and a dog on the balcony is barking incessantly.

Lala greets us with a faint smile, we hesitate for a moment and try to find somewhere to sit. We need to remind ourselves that this is the 21st century and we are in the capital of Armenia. However, this tiny space in this lonely neighborhood seems detached not only from Yerevan but from the rest of the world.

Until last summer, nobody gave Sari Tagh a second thought. Some didn’t even know of its existence.

On July 17, 2016, a group of armed men stormed a police station in Yerevan, Armenia, taking several officers hostage and demanding the release of Jirayr Sefilian, an opposition leader and a Karabakh War veteran. During the two-week siege, two police officers were killed. Most of the armed men, who called themselves the Daredevils of Sassoun (Sasna Tsrer) after an Armenian epic poem, had fought in the Karabakh War (1991-1994) and were also demanding the resignation of the country’s president, Serzh Sargsyan.

As the stand-off plunged the country into a state of chaos, thousands of people took to the streets to support the armed rebellion. Almost immediately after the siege began, authorities cut off water supply, natural gas and electricity to the entire neighborhood of Sari Tagh where the police station was located. They also cordoned off streets leading into the neighborhood. Many residents were caught in the middle of the siege by heavily armed men and in a strange twist of events, thousands of their supporters.

Two days after the stand-off began, on July 19, a group of residents went to where police had blocked the road leading into Sari Tagh demanding to know why their utility services had been suspended and roads cordoned off, effectively obstructing their freedom of movement and their ability to get to work. Their need for answers turned into a confrontation with security forces. Ten of those residents were arrested and charged with Article 316, Section 2 (Violence against a representative of authorities) of Armenia’s Criminal Code; they remain in pre-trial detention while the investigation continues.

Lala’s husband, Eduard Zeytunyan is one of those men.

Lala Bernecyan is originally from Yerevan. She and her husband moved to Abkhazia after they were married. In Abkhazia, Lala worked as a manicurist and her husband worked in construction with his brother. “We had a decent living,” she says. Every summer they come to Yerevan on the anniversary of their young son’s death. He died in a car crash on the road from Krasnodar. He was seven.

About last summer, Lala says they weren’t planning on staying. “But my husband got into trouble,” she tells us. “I’m thinking of giving up my Armenian citizenship now.”

Lala insists that the men of the neighborhood who went to see what was happening had nothing planned. They simply wanted to inquire about the situation. “At that point it had already been a few days that we did not have transportation … even the Internet was not working properly,” Lala explains.

Sari Tagh is perched on a hill and many of the roads in the neighborhood are very steep. “There are elderly women, people who needed to be at work at 9 in the morning and there was no transportation. So they went to find out what was happening,” she says.”They did not go to start a fight. Someone who wants to start a fight, doesn’t go in slippers.”

Police reports state that the men had gone with the intention to start a fight. “Someone who is expecting a confrontation does not pick up stones, he goes prepared. The police instigated the clashes,” Lala says calmly.

In the video footage taken by journalist Tehmine Yenokyan, there are several dozen residents arguing with police officers who had blocked the main road into Sari Tagh. At one point, one of the men starts throwing stones toward police and that’s when the situation spirals out of control. Several police officers sustained minor injuries in the melee.

The ten men who were arrested and charged with “violence against a representative of authorities” (Article 316 of the Criminal Code), if convicted, face anywhere from five to ten years imprisonment. “I have no idea how these ten men were singled out. You can see my husband in the video only for a second. He is not a hooligan, has no criminal record... it is not like his name was on a register somewhere at the police station,” Lala says.

The family members of the men who continue to remain in pre-trial detention, staged a sit-in for several weeks last month in front of the Prosecutor General’s office demanding their loved ones be released on bail until the end of the investigation. They have also appealed to the Prosecutor’s office asking that charges be overturned.

Lala says that several days after the incident, investigators came to her house looking for her husband. When she informed him that police were asking for him, Eduard voluntarily went to the police station according to Lala. He was apprehended on July 25 and continues to be incarcerated awaiting trial.

Libarid Simonyan is Eduard Zeytunyan’s lawyer. He told EVN Report that while the men have all been charged with the same article of the Criminal Code, it is not clear “who has done what, what action a particular detainee should be held responsible for,” he said.

Simonyan said that he raised this issue during a hearing, asking the Prosecutor’s office to specify who is being charged for what specific action and why they were being held in detention. He says he was told that it would be clarified during the investigation. “This means that they have detained people, kept them in prison, charged them, spent so much of the government’s resources and it is not even clear who has done what yet,” Simonyan said.

According to Armenian law, an accused can be held in pre-trial detention if he/she is a threat to society, is likely to obstruct the investigation or might try to escape the country.

Libarid Simonyan said that there are seven police officers who sustained minor injuries on July 19. “Overall, there are 20-30 witnesses and only two to three of them are civilians and even they seem to have been influenced,” he said. “They were made to watch the video footage, take note of who is doing what...in any case, we have not even reached a point in the investigation when we can interview the witnesses.”

Lala says that after her husband was detained, he asked to have a public defender and was assigned one only three days later.

A day after his arrest, on July 26, police called Lala and asked her for documents. “They called me and told me to bring some papers - my son’s death certificate, my daughter’s birth certificate, my husband’s military certificate and the clothes he was wearing on July 19,” she says. “It was a mistake on my part to take his clothes, I shouldn’t have done that. Now I am a material witness to my husband’s case.” As his wife, Lala has the right to decline from being a witness. “I still can’t bring myself to understand how it was that I signed those documents. I had no experience. Had I known, I would not have signed a single paper,” she explains.

Within 20 days of his arrest, Eduard Zeytunyan was officially charged with Section 2 of Article 316. “That’s a heavy accusation without proper investigation,” Lala says “There have been 19-20 hearings so far. Some were postponed because the judge didn’t show up for the first two-three times.”

Libarid Simonyan said that one of the irrationalities of this situation is that investigators have separated the case of the ten men into four separate ones. “Four people are being tried together, three separately, two and then there is one person whose trial is also separate even though they are all charged with the same article for the events of the same day,” he said.

Simonyan said he didn’t want to speculate, but said this process is pointless and tried to explain this course of action taken by the Prosecutor. “The seven police officers who were injured and about 20 officers who are witnesses to the case are obliged to appear in court, at least the seven who sustained injuries,” he said. “Now, they have to be part of the same trial four times over and sit in court waiting to be called to the stand. Naturally, even if they have learned by heart what they need to say, there are bound to be contradictions in their accounts.”

The lawyer told EVN Report that they already have one officer on record who has been interrogated three times and each time says completely different things.

“Putting aside the unnecessary expenses - keeping ten people in pre-trial detention, holding the same trial four times over, doing the same investigation four times over - the criminal code states that all cases pertaining to the same incident should be joined,” Simonyan explained. “But imagine, if they did that the families of all ten accused will be in court at the same time for the same trial. A large group of people will witness the absurdity together and I think the justice system and the government want to avoid this in case there is an outcry or the families consolidate their anger.”

Narine Ghazarian got married in June 2016. Two months later, her husband Hrach Boyajyan was arrested for his involvement in the July 19 incident in Sari Tagh. He, too, remains in detention.

Narine is currently back home with her mother while her husband is in prison. She is angry and frustrated. “The boys went down to voice their concern about the situation with the transportation, water, electricity,” she says adding that transportation was the primary issue. “You know, we do not have that much money, we would be stuck at work.”

She says that during the scuffle, police officers were cursing the men and their families. “We even know which police officer is the one cursing families, children. As women, we would not have taken it, imagine how the men felt,” she says.

On the day her husband joined the other men of Sari Tagh, he was wearing a bright yellow T-shirt. “If a person wanted to do something, if he was going there to stir trouble, he would have worn black, put on a hat, sunglasses…” Narine says that her husband, like the others, was frustrated by the situation of the neighborhood.

Narine says that she didn’t even know her husband had been at the confrontation. However, when he found out that people from the neighborhood were being arrested, he fled to Georgia. “When he thought he might face five to ten years in prison, he panicked and took off,” she says. He was apprehended on August 30 and has been in prison ever since. “We didn’t know that he was wanted by police. We just knew that they were after all the men in Sari Tagh and they were bringing them in one by one.”

“My husband is a hardworking man, he has never had any trouble with the law, he is a law-abiding citizen,” she says. “This is why I am so upset - if a person made a mistake once, it does not mean that you have the right to destroy his life. I’m not even saying acquit him, let him out on bail.”

Narine says that for the past nine months, they have been back and forth to the courthouse and there is no progress in the case. “The first couple of times, the judge didn’t show up. Then we complained. Then the public defenders wouldn’t show up...this process is going to take two years and they haven’t even started questioning the witnesses,” she says.

“I just want my husband to come home,” Narine says. “Only two of the men have prior convictions, one for ditching his military service and the other one for bride abduction. This is the first time for my husband. Change his charge from section two to one of Article 316 and pardon him, he should be given a chance to live normally, to not make the same mistake again. But now if you convict him, put him in jail, you’ll have damaged his good name, reputation, future. I just can’t accept this.”

Another Sari Tagh resident, Harutyun Torosyan was apprehended on July 20, a day after the scuffle with the police. His brother Toros Torosyan says he didn’t even know his brother had gone with the others to talk with security forces.

“There are about 20 thousand residents in Sari Tagh and we have only one bus route,” Harutyun says. Although most residents of the neighborhood work in the city, Torosyan says that they have always been ignored by the municipality. “After the scuffle on the 19th, the roads were suddenly reopened, transportation was allowed back into the neighborhood, the water, gas and electricity and the Internet were turned back on,” he says.

His brother is being held at the Nubarashen penitentiary known for its overcrowding and poor conditions for inmates. Torosyan says that the biggest problem is that no one can say for certain who among the detainees did what on that day. “Everyone has to answer for their actions, but who did what?” he asks. “They have been in prison for ten months now - can someone clarify what my brother did exactly and to whom?”

According to Torosyan, the seven injured police officers cannot identify those who injured them. “Whoever was caught on video, was simply picked by the authorities,” he says.

According to their lawyer, Libarid Simonyan, the reason for the delay is to try and diminish public hype over the case. “The longer it drags on, less and less media representatives and NGOs will remain interested in the case,” he said.

Simonyan believes that if they separate each individual case, then Article 316 will not stick. “Some of the detainees, who actually threw stones, can be prosecuted with Article 316, section one or two and the rest who have done nothing, who were simply standing there or demanding that the roads to Sari Tagh be re-opened, or electricity and water turned on, which is not a crime, should be released,” he said.

Nonetheless, the lawyer says that their actions cannot be classified as an offence according to the specific article they are charged with. “There is no prior intent or agreement by a group of people to clash with police, which is what Section two entails,” he said. “Each person there is responsible for his own actions. The principle of collective responsibility does not work here.”

Some of the family members met with the Prosecutor General over a month ago to discuss the case. According to Torosyan the Prosecutor said that the police officers cannot say for certain who attacked them. “He couldn’t give us any concrete answers,” Torosyan explained. “The police instigated the scuffle, it’s like an Indian soap opera.”

Toros Torosyan does not have a criminal record according to his family. In the video he is mostly watching calmly, but at one point in the altercation, he throws a stone in the direction of the police.

In an interview with azatutyun.am, the director of the General Prosecutor’s Indictment and Appeals Department Gevorg Baghdasaryan said that the accused are charged under article 316 because there was a premeditated intent to harm representatives of the state. He said that family members of four of the accused met with the Prosecutor General, who “gave concise answers to the families.” Torosyan who was one of those present at the meeting with the Prosecutor said he was told that if his brother pleads guilty, he would be released. However, none of the accused are prepared to do that.

When the reporter for Azatutyun asked Baghdasaryan how Article 316 could be applied, if the police officers sustained only minor injuries, Baghdasaryan said that even minor injuries can be considered dangerous to the health of the police officers and insisted that there is no political motivation in holding the accused in pre-trial detention. Regarding the fact that the police officers in question cannot identify the perpetrators, Baghdasaryan said, “When there are so many people involved, it is normal that the injured cannot recognize those who struck them.”

The families of the accused insist that charging the men under Article 316 is excessive and believe it is being done to serve as an example to others.

“There is not one single person who has been charged who is innocent - they used their arms, legs and stones to deliberately harm the police officers who had gone to do their job,” Baghdasaryan said. “Police officers were there to ensure the security of the people of Sari Tagh and to carry out their duties - no one is allowed to attack police officers.”

According to the official, the extent of the injuries is not important, but rather the fact that there was intent to harm them and therefore the charge brought against the men is appropriate.

Armenia’s Human Rights Ombudsman Arman Tatoyan told EVN Report that while he cannot comment on the specific case as it is still under investigation, the practice of detentions in Armenia should be changed. “Detention should be used as a measure of last resort,” Tatoyan said. “We don’t have presumption of liberty.” He went on to say that more than 90 percent of motions submitted to the court for detention are granted and this practice must be reevaluated.

The Ombudsman stressed that there are limitations to his jurisdiction and that his office cannot intervene in this specific case. Regarding the separation of the cases into four separate ones, Tatoyan said only that state resources should not be abused and if the lawyers have concerns, they should submit those to the investigation bodies and the court. “While we cannot intervene in the case, prison conditions however are under the full attention of the Ombudsman’s office,” Tatoyan said.

Today, Toros Torosyan’s family, like all other families who have loved ones in prison, must supply them with everything - from soap to bedding to food. They say that the conditions in Nubarashen Penitentiary are terrible. “We are allowed to take 70 kilos a month of goods to Toros,” Harutyun Torosyan’s wife explains. “We have to boil his clothes to get rid of the stench and the bugs.”

While Lala’s husband remains in prison, she is taking care of their daughter, her sister and her aunt’s 13 year-old grandson. She tells us that her daughter needs to see a psychologist and working as a manicurist, she can barely make ends meet. She says that while she is allowed to take up 70 kilos of goods to her husband, she can’t get enough money together to provide him with what he needs. “No one can eat prison food,” Lala says.

Armenia has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights adopted by the General Assembly of the UN in December 1966 and in force since March 1976. Articles 9.3 and 9.4 of the convention restricts the use of pre-trial detention, “requiring it to be imposed only in exceptional circumstances and for as short a period of time as possible.”

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures, the “Tokyo Rules” states that “pre-trial detention shall be used as a means of last resort in criminal proceedings, with due regard for the investigation of the alleged offence and for the protection of society and the victim.”

As Armenia’s Ombudsman said, pre-trial detention interferes with one of the fundamental human rights, the right to liberty. That is why there is the global understanding that the use of pre-trial detention should be limited to exceptional cases and needs to be justified on a case-by-case basis. International human rights law prohibits arbitrary and unnecessary use of pretrial detention.

Regarding those held in pre-trial detention, the United Nations’ Center for Human Rights states: “Their legal status is undetermined - they are suspected but have not yet been found guilty - and they are also under enormous personal pressures such as economic loss and separation from family and community ties.”

Today, ten months after the confrontation, it remains unclear how long the ten men of Sari Tagh will remain in pre-trial detention while the investigation continues.

While Lala is calmly telling us her story, her daughter comes out of the bedroom. She sits beside her mom and begins playing with her hair. Lala looks down at her and smiles. After suffering so much loss in her life, and now having to struggle alone, Lala is nevertheless resolute. She says she will keep fighting to have her husband released.

On May 30, Lala and the other family members began another sit-in, this time in front of the government building in Yerevan.

-------------------------------------------------------------

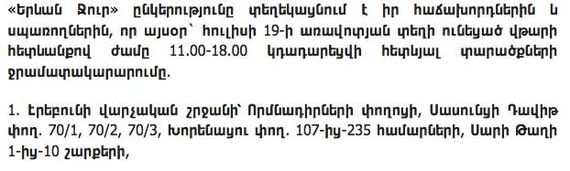

Armenia's Criminal Code

Article 316. Violence against a representative of authorities.

1. Violence or threat of violence, not dangerous for life or health, against a representative of authorities or close relatives, concerned with performance of his official duties, as well as hindrance to the representative of authorities in the execution of duties under law, is punished with a fine in the amount of 300 to 500 minimal salaries, or with imprisonment for the term of up to 5 years.

2. Resistance to the representative of the authorities while in the line of duty or forcing him to perform obviously illegal actions, committed with violence or threat thereof, is punished with a fine in the amount of 300-500 minimal salaries, or arrest for up to 2 months, or imprisonment for up to 1 year.

3. Violence against the persons mentioned in part 1 or 2 of this Article, which is dangerous for life or health, is punished with imprisonment for the term of 5 to 10 years.

4. In this Code, by a representative of authorities we mean, the official of state and self-government bodies who is vested with the power to command to persons who are not under his subordination.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Constitution of Armenia:

Article 27. Personal Liberty