Tue Oct 12 2021 · 25 min read

From the Arab Spring to Afghanistan: Lessons For Armenia

By Paruyr Abrahamyan

Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Back in the 2010s, Armenian policymakers were too short-sighted to assess the implications that the Arab Spring had for our own country. Waves of revolutions, anti-government demonstrations and armed rebellions led to larger regional instability, violent civil wars, growing sectarianism, religious and proxy wars, economic decline, mass migration and the collapse of state systems and societies in Syria and Libya. Those battles are still being fought 10 years later and continue to impact Armenia.

The protest motto in these Arab countries was "Bread, freedom and social justice". The main driving force behind the protests were middle-class, educated youth and labor activists dissatisfied with the worsening economic situation, growing unemployment and extreme poverty, especially after the 2008 financial crisis. These pressures bred dissatisfaction with the corrupt political regime and concentration of national wealth in the hands of a few families. A number of internal and external factors contributed to the unrest, such as climate change and severe drought, ethnic and religious tension, and social media access poking holes into state censorship. However, there were deeper geopolitical and geo-economic factors that must be considered as well.

After U.S. troops left Iraq at the end of 2011, the country rapidly turned into a haven for radical Islamist parties. Extremist groups filled the power vacuum, eventually creating the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) that conquered Iraq's western provinces and took advantage of the civil war in Syria to cross into that country as well. These early successes inspired thousands of other Islamist fighters from all around the globe, including Western nations, to join the pan-Islamist cause and restore the Caliphate. Along with the fighters came a massive flow of weaponry and external funding as well.

The question of why the Americans left Iraq is an important one in itself, but for Armenia it is more pressing to understand what happened after they did. On August 30, 2021, the U.S. also completed its evacuation from Afghanistan. We need to learn the lessons of the Arab Spring in order to be prepared for the geopolitical shifts that have once again already been set in motion. While Armenia’s ability to impact the situation is limited, there are important steps that can be taken now to mitigate risks in the years that follow.

When Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in Tunisia, it did not really register on the Armenian radar. But soon the wave of mass protests spread over Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Bahrain. Even then, it was seen as a distant phenomenon. Once it reached Egypt and Jordan, the first small Armenian communities began to feel the heat; about 5,000 Armenians live in Egypt and nearly 3,000 in Jordan). The country that was eventually hit hardest, however, was Syria, where around 100,000 Armenians were directly impacted by the ensuing humanitarian disaster. The civil war there, which also became a proxy battle for regional heavyweights, forced more than 6.6 million people to flee the country. Among them were nearly 70,000 Armenians, 14,000 of which found shelter in their historical homeland, while the rest left for Lebanon, Europe, the U.S and Canada. Many Syrian-Armenians lost all they had, their homes and businesses, their savings and livelihoods, sometimes their family members and loved ones. While there was some silver lining as the inflow of Syrian-Armenians into Armenia had a palpable positive impact on the local society in terms of bringing in a skilled workforce and innovative ideas, nevertheless, it would have also represented a serious challenge and socioeconomic burden for the state budget, if it wasn’t for external support.

Ripples From Afghanistan

Today, similar processes are taking place in Afghanistan. Once again, the implications for Armenia are not being taken seriously enough. Let’s not forget that it was the battle hardened mujahideen of Afghanistan whose jihadist ideology led them to join Azerbaijan’s fight against the Armenians of Artsakh during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. An estimated 5,000 Afghan fighters were sent to Azerbaijan, supported by Pakistani special services, in the early 1990s. They crossed from Afghanistan to Iran under cover of being “refugees”, and then made their way toward Azerbaijan. There is evidence that these troops were paid an average of $1,500, paralleling the Syrian mercenaries recruited and sent by Turkey to Azerbaijan during the 2020 Artsakh War.

There are already allegations that al-Qaida militants from Afghanistan have begun to be transported to the territories that Azerbaijan gained control over after the last war. Besides the possibility of direct military engagement, the developments in Afghanistan also introduce indirect consequences for Armenia.

The most pessimistic forecast for Afghanistan envisions it as a restored incubator of international terrorism, the source of new flows of refugees and drugs. It could spread the ideas of radical Islam to Central Asia, emboldening local cells gain power in neighboring countries as well.

According to official data, there are currently about 110,000 Armenians living in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan; other unofficial reports put the number closer to 170,000. If a new round of destabilization ensues, Armenia may be the destination for a new wave of mass migration from Central Asia. Of course, a significant percentage, especially Hamshen and Muslim Armenians, would primarily flee toward Russia (their Russian language skills are probably better than their Armenian); however, tens of thousands of repatriates could again put Armenia under hard socioeconomic pressure. In addition, the economic and political capital of Armenians accumulated there throughout decades is at risk, thus weakening our positions on this important frontline in the heart of the Turkic world.

While we have already lost a lot of precious time, it is still absolutely necessary to work intensively with our communities in those countries, to clearly explain the possible scenarios, assess the threats and design an action plan that can mitigate the risks.

A very concrete step could be to open direct flights with each country. This would encourage our compatriots to come to their homeland, strengthen ties, take part in cultural and educational exchange programs, and get acquainted with business and investment opportunities. This way, if things do end up going south, the adjustment to resettling in Armenia could be handled more smoothly than was the case for the Syrian-Armenians. Ideally, some would decide to move before it became an existential necessity.

Afghanistan Today

Even though the Taliban managed to quickly fill the power vacuum left by the U.S. withdrawal, they have not yet filled the legitimacy vacuum. Their historical experience and well-developed political instincts will help in learning from past mistakes and shortcomings during their tenure in power from 1996 to 2001. They also understand that the world and the realities in the region are different than they were a quarter century ago. Over the past 20 years, a new generation of young people has grown up in Afghanistan. The country has grown more heterogeneous and diverse. In Kabul, you can meet youth who are plugged in to the greater world, wear jeans, celebrate Halloween and listen to rock music. To gain international recognition and fill the legitimacy vacuum, the Taliban is now trying to present itself as more inclusive, whether or not that is reflected in facts on the ground.

The Taliban have been promising not to cause trouble for their neighboring countries, not to support terrorist organizations, and to establish an Islamic system in which all Afghans will have equal rights. They push pictures and videos driving bumper cars and pedal boats in a bid to get off different sanction and terrorist organization lists. So far, it hasn’t worked. The new interim government failed to include all ethnic, religious and political minorities or pursue a moderate domestic and foreign policy.

Regardless, it looks like a new round of the “Great Game” is being played in Afghanistan, making it an important part of a wider Asian chessboard on which major powers are in a strategic competition. Situated in between Russia, China, Iran, Pakistan and India, and at the crossroads of intercontinental land routes linking East to West, the “Heart of Asia”, as Indians would call Afghanistan, finds itself in a complex set of global and regional knots, where the goals and priorities of key players are very different and often contradictory.

If things remain stable, China, Russia, Iran and Pakistan will benefit the most out of the new realities in Afghanistan. That explains why, while the United States and other Western states urgently evacuated their diplomats and citizens from Afghanistan, China, Russia, Pakistan and Iran stayed put. Moreover, the Taliban announced that Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, as well as Turkey and Qatar, were invited to the inauguration of the new government. These are the countries that are highly likely to be among the first to recognize the legitimacy of the Taliban in Afghanistan, although, so far, they are not in a rush and are looking for more positive signals from the interim government.

On the other hand, if things begin to fall apart, these countries also bear the greatest risk. The regional players—China, Russia, Iran, Pakistan and the Central Asian states—are interested in ensuring stability in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of U.S. troops. They all have long benefited from the regional security and stability provided by the U.S. and NATO military presence in Afghanistan.

The risks of destabilization are aggravated by the fact that today every third Afghan doesn’t know where to find their next meal, poverty is growing dramatically and social services are close to collapse. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 18 million people, almost half of the Afghan population, need urgent humanitarian aid. Meanwhile, about 40% of the country's GDP depended on investments from abroad, and many international assistance programs to Afghanistan were stopped after the Taliban came to power. In addition, the country is expecting a harsh drought—the second in four years. By the end of the year, just as winter approaches, many may be left without food. Inflation is rampant as some products have doubled in price. There is not enough medicine, public institutions do not work, there is no police on the streets, no order, even hospitals are closed, and all this during a pandemic.

$10 billion in foreign reserves belonging to the Afghan Central Bank have been frozen due to the Taliban’s unrecognized status, further worsening the country's economy and financial situation.

Another crucial factor feeding negative scenarios is that, according to 2017 data, about 10% of the population in Afghanistan owns firearms. What will the unemployed, hungry population do with those arms in hand? In Iraq, after the U.S. troops left the country and foreign aid stopped coming in, the disappointed and desperate people became easy targets for recruiters from various radical Islamist groups.

In addition to all this, Afghanistan has a very complex ethnic composition. The Taliban is heavily Pashtun, but more than half of the population has different roots, including Tajiks, Hazaras, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Turkmen and others. Therefore, when upheavals occur, there is the risk of a sectarian civil war with dire consequences. Even Pashtuns themselves are divided into many clans and tribes (Durani, Ghilzai, etc.).

The Taliban itself is not heavily centralized. With external enemies gone, internal divisions can become more pronounced, especially between moderates and radicals. Among the latter is Mullah Mohammad Hassan Akhund, one of the Taliban’s founders and the current Prime Minister, who is on the UN Security Council sanctions list, as well as Sirajuddin Haqqanim, the new interior minister and head of the Haqqani militant group that is considered a terrorist organization in the U.S. because of its close ties to al-Qaida and numerous terrorist attacks in Afghanistan during the last 20 years.

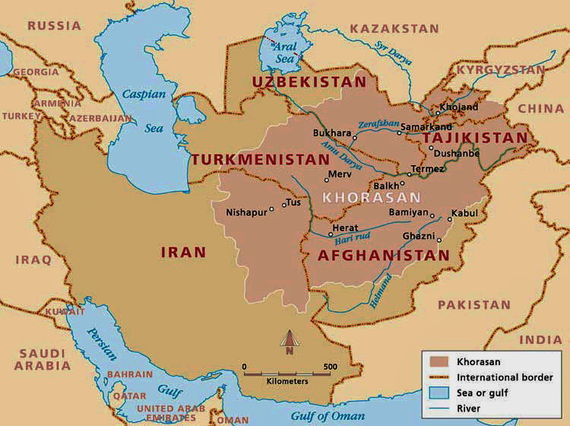

More radical elements have already begun to challenge the Taliban. The Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP) has been present in Afghanistan since 2015. Their name refers to the historical name of the region. ISKP have religious ideological differences with the Taliban. The latter are followers of the more moderate Deobandi and Hanafi schools of Islam, while ISKP aligns with the most radical elements of jihadism and Salafism. Also, the Taliban seem to be mainly a Pashtun nationalist movement with an objective to create a Pashtun Islamic Emirate and establish Pashtun domination over the non-Pashtun territories in Afghanistan. In contrast, ISKP’s goal is to create a global Islamic caliphate, which requires an irreconcilable struggle against both external infidels and internal “heretics''. From time to time, they fight and compete for control over more territory, power and logistics corridors, challenging the Taliban’s myth of invincibility. Nevertheless, we can’t fully exclude the possibility of collusion between the Taliban and other radical Islamist groups.

The Taliban and Radical Islamists

Interactions between all these groups have a long history, going back to the war against the USSR in the 1980s. Many anti-Soviet training camps located in the territory of Pakistan were coordinated by the Pakistani Interdepartmental Intelligence Services and sponsored by some Gulf countries. Those camps later gave birth to the Taliban and al-Qaida in the late 1980s and early 1990s. ISIL itself was spun off from al-Qaida in Iraq. So, all these elements have common roots, share similar ideologies, and even have family ties. In June 2020, ISKP announced Shahab al-Muhajir as its new emir in Afghanistan—he is a former field commander in the Haqqani Network. There are multiple reports, including by the Afghan Ministry of Defence, about coordinated attacks carried out by the Haqqani Network and ISKP fighters.

Moreover, it seems like there is an ongoing "Pashtunization" of the ISKP. Pashtuns (primarily Pakistani) are eclipsing a traditionally Arab leadership. The "Pashtunized" form of ISIL ideology are more acceptable to Afghan Pashtuns. Besides, both groups are of one mind with regard to who are the “wrong Muslims”, i.e. the Afghan Shia Hazaras and non-Pashtun minorities against which they have carried out numerous deadly attacks.

The assumption that the Taliban will only be preoccupied with internal problems is very debatable. As in the late 1990s, the Taliban still simply does not have enough clout to be more active in international affairs, but can adopt indirect plans for expansion—through supporting various regional radical Islamist groups. In the 1990s, they did not enter into direct fights against the Central Asian regimes, but they still actively supported organizations like Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and other extremist groups located in Central Asia through al-Qaida. In a recent interview with BBC Urdu, the Taliban's spokesperson claimed: "We have this right, being Muslims, to raise our voice for Muslims in Kashmir, India, and any other country." Meanwhile, in their congratulatory message to the Taliban for their swift takeover of Afghanistan, al-Qaida also called for “liberating” the Levant, Somalia, Yemen, Kashmir and the rest of the Islamic lands “from the clutches of the enemies of Islam.”

Accordingly, the key question becomes whether the Haqqani Network or less radical groups will dominate within the Taliban, or what will happen next if the Haqqani does eventually take full control and cooperates with ISIL, al-Qaida and their affiliates in the post-Soviet space, China, Iran or elsewhere? The withdrawal of the Americans was a powerful advertisement for jihadism around the world. From the outside, it looks like the jihadists brought a superpower to its knees (or at least outlasted them), making the Taliban a fashionable brand that can potentially inspire and embolden other radical elements or "sleeping cells" in other parts of the world.

It is obvious that, even if Islamic State was knocked out of Iraq and Syria, it was not completely defeated. According to some reports, the number of remaining ISIL fighters is as high as 30,000. The Russian Defense Minister recently stated that, even though he very much hopes that some kind of consensus and inter-ethnic reconciliation will be reached in Afghanistan, he clearly sees that ISIL units are showing a growing interest in relocating to Afghanistan and Central Asia from different regions, including from Syria and Libya.

Interest in Afghanistan is not new for ISIL. In October 2016, referring to intelligence reports, Afghanistan’s then-First Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum warned that ISIL planned to deploy thousands of militants from Iraq and Syria to the northern and eastern provinces of Afghanistan by the spring of 2017. According to him, the foreign fighters are mainly natives of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and the North Caucasus, as well as many Arabs and Uyghurs.

The emergence of the first small groups of ISIL supporters in Pakistani and Afghan territory is believed to have started in the fall of 2014. Not long after, a branch of the Pakistani Taliban swore allegiance to the head of ISIL Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and infiltrated into Afghanistan. These groups later played an important role in the formation of ISKP.

During the Tehran Forum that gathered the heads of Security Councils and National Security Advisers from Iran, Russia, China, India, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan on December 18, 2019, Secretary of the Russian Security Council Nikolai Patrushev claimed that the situation in Afghanistan was unstable and deteriorating, and that ISIL continues to consolidate its forces in Afghanistan, preparing a bridgehead to invade the Central Asian countries with the ultimate goal of recreating the so-called "Greater Khorasan”. Patrushev and the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran, Rear Admiral Ali Shamkhani, went even further, saying that the process of ISIL’s infiltration into Afghanistan was not accidental or spontaneous, and that there was a lot of evidence pointing to direct U.S. involvement in transferring the remaining ISIL fighters from Syria and Iraq to Afghanistan.

According to various estimates, including by the UN and the Russian SVR, ISKP consists of up to 4,000 fighters, composed of predominantly educated youth, more efficient and decentralized networks.

Due to the growing instability in Afghanistan and further isolation of the Taliban, ISIL will have a chance to gain a territorial base lost in the wider Middle East, as well as persuade part of the Taliban to migrate into ISKP. In turn, this can feed ethnic separatism in the country, as happened with the Kurds in Syria and Iraq after the state collapse and rise of ISIL. Tajik, Uzbek and Shia-Hazara minorities could claim their independence, referring to their right of self defense in a chaotic environment. The same can happen with the Baloch people by forming a Baloch state within the territory of Afghanistan, which can trigger similar processes in Iran and Pakistan. All this will inevitably be accompanied by the intensification of narco-trafficking and mass migration, taking into account that the production and trade of drugs bring up to $2 billion a year in revenue, a crucial source of income for the Taliban and other extremist groups.

According to UN forecasts, by the end of 2021, about half a million Afghans will have left the country. The refugee flows increase the chances that extremists will exploit the situation to infiltrate refugee camps in neighboring countries, which is a concern for Russia.

American Fiasco or Gambit?

All of this could explain why the Biden administration considered such a quick withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. As President Biden noted, Washington had only two goals in that country: to find and punish those responsible for the September 11, 2001 attacks and to make sure that al-Qaida could not use Afghanistan as a platform for subsequent attacks on the U.S. He also noted that the U.S. has other “essential and vital interests in the world” that cannot be neglected, and “endless struggle in a conflict” is not part of them. "Our true strategic competitors China and Russia would love nothing more than the United States to continue to funnel billions of dollars in resources and attention in stabilizing Afghanistan indefinitely," Biden added.

The U.S. stance seems to be quite clear: their departure from Afghanistan can be explained by their plans to confront China in the Asia-Pacific region while leaving China, Russia, Iran and other neighboring countries to confront the security vacuum in Afghanistan. They most probably calculated that an "inclusive government" in Afghanistan would not be possible, and that the Taliban’s fear of remaining internationally isolated is very likely. In other words, the Americans understood that the processes in Afghanistan were highly likely to stay unmanageable and chaotic taking into account the unpredictability of the Taliban, the growing humanitarian disaster, further segregation of society, inter-etnic and fractional conflicts, turning the country into a new platform for deployment of various cross-border extremist groups that will have greater freedom of action. The British Defense Secretary Ben Wallace, for example, openly encouraged Afghan refugees not to wait for evacuations at the airport and instead flee through land borders.

China as the Potential Winner?

After the Taliban takeover, many politicians and experts, both in the U.S. and abroad accused President Biden for the hasty withdrawal of American and NATO troops from Afghanistan, calling it a surrender and a political humiliation for the U.S. and the West in general. Critics claimed that the Afghan army, on which the Pentagon spent nearly $88 billion, fled or sided with the Taliban while U.S. forces left behind thousands of pieces of military equipment and weapons, estimated in the billions of dollars, allowing the militants to considerably increase their offensive capabilities, and also opening the doors of strategically important Afghanistan to China and Russia.

The main geopolitical adversaries of the U.S. used the chaos amid the withdrawal to undermine the credibility of the promises the Americans had made to their Asian allies, further generating anti-American moods in the region, and used it as an opportunity to weaken the positions of the U.S. and the West in their global hybrid war.

However, the primary interests of China in Afghanistan remain regional security and political stability to secure its economic projects, gain access to the region’s rich mineral resources and push forward more overland transit routes for its exports to reach Europe within the Belt and Road Initiative. Therefore, first of all, China is preoccupied with the potential security threats coming from Afghanistan which was previously a safe haven for extremist groups operating in the Xinjiang region of China such as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (the Trump administration removed it from the list of terrorist organizations in 2020). It is likely China promised the Taliban economic investments and assistance in reconstructing infrastructure in exchange for guarantees that the Taliban completely cuts off ties and detains any transnational terrorist groups that threaten Chinese interests.

The Taliban's political leaders have assured Beijing that it has nothing to fear as they fully respect Chinese territorial integrity, while China chose to become an important economic partner for the Taliban to prevent the influx of Islamic extremists into its territory. Equally important is that China retained its embassy in Kabul and established strong relationships with the Taliban leadership. Nevertheless, there is no guarantee that the Taliban will be able to control all the factions that have fought under its flag over the past 20 years, some of whom are powerful and semi-autonomous. China's dilemma is mainly with the Haqqani network linked with the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) who is believed to be involved in the July 14, 2021, bombing in Pakistan that killed nine Chinese workers and the suicide bomb attack on a Chinese convoy in Gwador a month later on August 20.

China’s next major interest is gaining a foothold in the resource rich country. According to different estimates, Afghanistan's mineral reserves could be at $1-3 trillion in monetary terms. The country has rich reserves of copper, iron ore, aluminum, gold, silver, zinc, mercury, rare metals including lanthanum, cerium, neodymium, and possibly the world's largest reserves of lithium, which is a key component for the production of ionic batteries.

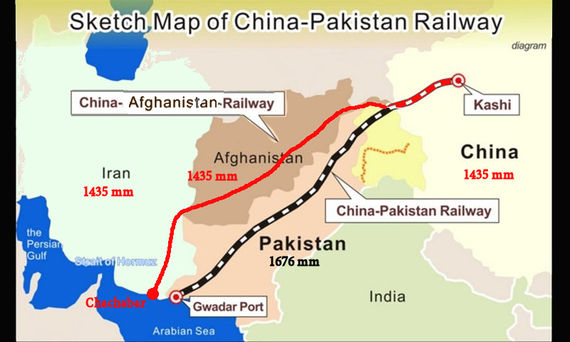

Finally, China sees Afghanistan as an important part of its Belt and Road initiative. A slight look to the map will prompt the geostrategic location of the country in being another alternative land route for China to export its goods to the region and beyond to the West. If the existing or most potential routes connecting China and Afghanistan pass either through Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, or through Pakistan, China most probably would also want to have a direct connection with Kabul through the Wakhan Corridor, bypassing the Turcic countries, Tajikistan that has complicated relations with Afghanistan, as well as Pakistan, which is a formally an ally (also against India) and a key part of the BRI through Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) but also is an unpredictable and unstable actor being a US major non-NATO ally and having close ties to Turcic world. Besides, Afghanistan is the shortest route for Beijing to the Indian Ocean and a direct link to Iran.

To achieve these goals, China’s most important task is to do everything possible to have a stable and secure Afghanistan, even if it is Taliban-controlled, without which China and other investors would not be able to accomplish their economic objectives.

This already took place in 2008 when two Chinese state-owned metallurgical companies won a 30-year tender for the extraction of copper from the world's largest undeveloped deposit in Mes Aynak, 40 km southeast of Kabul, although mining has not commenced because of security issues. Later, in 2011, Afghanistan signed a 25-year contract with China’s National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) to begin operations at the largest oil and gas fields discovered in Afghanistan.

The Taliban understand that without foreign capital, technologies, infrastructure and safety, they will still not be able to take advantage of the country’s natural wealth, human capital and advantageous geographical location in the center of the Great Silk Road, which could help them raise living standards, spend on healthcare, education and science, thus proving their legitimacy and popularity.

It is also important in terms of China’s ambitions to seek regional and global hegemony by challenging the Americans. Therefore, Afghanistan will be a test of whether China is able to fulfill its plans to become a lighthouse for the countries in the region. Apparently, China expects the Taliban to play an active role in regional security and peaceful development.

What Is Russia’s Stake?

Russia does not have a common border with Afghanistan; they are separated by Kazakhstan, and then Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Nevertheless, the growing instability in Afghanistan after the American withdrawal and the potential of a civil war creates serious security threats for Russia and the countries of Central Asia, whose security Moscow guarantees within the framework of the CSTO (Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan) or close bilateral relations (Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan).

Even though in Russia the Taliban is considered a terrorist organization, Russians have long been in direct contact with their leadership, publicly claiming that the seizure of power in Afghanistan by the Taliban can have a positive impact on regional stability and development. Moreover, similar to other countries Russia didn’t evacuate its embassy from Kabul and was invited to the inauguration of the new Government. This seems to be a response to many statements made by Taliban representatives that they have no intentions to attack or cause troubles for Central Asian countries. So far the Taliban have been saying what they want to hear in Moscow and in Central Asia. But can they be trusted?

On August 11, 2021, Russia’s Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that the Taliban had taken control of the borders with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan adding that they had promised not to attack neighboring countries. He also said that Russia will use its bases in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to protect the CSTO borders "in the event of direct aggression," since it also concerns the security of Russia.

However, for Russia the main task is to have a friendly and stable government in Afghanistan and prevent the proliferation of terrorism and extremist ideologies in Central Asia. Russia has a visa-free regime with almost all of these states, which means that refugees, narco-trafficking and radical elements can infiltrate into Russia. In the late 1990s, Afghanistan became a hotbed of terrorism, and Russia fears a repeat of the situation. The Russians have not forgotten their experience in the Soviet-Afghan war, as well as the killings of 25 Russian border guards on the Afghan-Tajik border in 1993, during the civil war involving militant jihadists in Tajikistan, where one of the terrorist commanders was the future leader of Chechen fighters, Khattab, who earlier had fought against the USSR in Afghanistan, then transferred his "jihad" to Tajikistan and later to Chechnya. Russians, of course, also remember the 1999 "Batken War'' in Kyrgyzstan, when representatives of the al-Qaida-related terrorist group Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan stormed the country, organized terrorist attacks in Tashkent, clashing with security forces in the Batken region of Kyrgyzstan.

Russians also understand the close ties of North Caucasian militants with the Taliban through al-Qaida, who actively participated in two Chechen wars and carried out many terrorist attacks in Russia. Field commanders like Shamil Basayev and others were trained by instructors sent by al-Qaida from Afghanistan. For this reason Russia listed the Taliban as a terrorist organization for supporting the independence of Chechnya and the recognition of Ichkeria.

In addition, there are about 5,000 Central Asian militants who left for Syria and Iraq, and who along with North Caucasians from Russia and Uighurs from China, fought for ISIL in the Middle East. Many of them are currently returning back to their home countries or being relocated to northern Afghanistan laying a time-bomb to potentially destabilize Afghanistan. That is also why the countries of Central Asia look at Afghanistan with fear and concerns. Although it is highly unlikely that the Taliban will invade Central Asia, it definitely poses a very serious indirect threat as there are powerfull Islamist movements in these countries that are affiliated with ISIL and al-Qaida, such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan or Jamaat Ansarullah. Central Asian leaders are also concerned that the Taliban’s success could revive these extremist groups capable of shattering their domestic stability and order, and undermine secular governments. They have already witnessed many terrorist attacks even when the U.S. military was still in control of Afghanistan. These include the attacks on the Ishkobod border post on the border between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in November 2019; the killings of four tourists in the Tajik mountains; an attack on the police station in Aktobe, Kazakhstan, in June 2016, killing 25 people; the terrorist attacks in Bishkek in August 2016 when a suicide bomber rammed the gates of the Chinese embassy and blew himself up. This all was carried out by local radicals linked to ISIL.

In general, the demand for the ideas of radical Islam, teachings of Salafism and Wahhabism in Central Asia are getting more popular (foreign preachers and recruiters are actively working) and there are many reasons for that such as the spread of poverty, unemployment, growing stratification of societies, agrarian overpopulation with a shortage of water and fertile land, degradation of social security systems, education and healthcare created during the Soviet era, high level of corruption, social injustice, growing disappointment with the authorities, insecurity in the future, plus "corona crisis", as well as serious interstate conflicts, especially in the Fergana Valley, where the contradictions between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in the spring of 2021 led to large-scale military clashes.

Why did so many people join ISIS when they were gaining power in Syria and Iraq? Not because they desperately wanted to fight Asad or Saddam’s regimes but mainly because they believed it was a chance to live in an islamic justice, to get a job, be surrounded by like-minded people and have security and stability (of course nourished with Islamist propaganda and information manipulations using the latest means of communication by the Islamic State).

So, the ideological vacuum and the identity crisis formed after the collapse of the USSR along with the factors mentioned above create solid conditions for a detonation in Central Asia, especially when the radicalized parts of the populations have been long infiltrated into the power structures of these countries creating their sleeping cells. A good example is the case of the Dushanbe’s OMON commander Colonel Khalimov who fled to IS with a group of officers. It is obvious that the triumph of radical Islamist ideology and possible Taliban further successes in Afghanistan will become an inspiring call for those groups to activate, and Russia and the CSTO will not be able to solve this problem with the help of exclusively military presence and exercises.

On the other side, the events occuring in Afghanistan obviously open new doors for opportunities for Russia as well. To a certain extent the current situation plays into the hands of Russia, who tries through its propaganda machine, to use the Taliban and other extremists in creating an illusion of danger for the Central Asian countries, claiming that only Russia is able to protect them.

For example, in one of his earlier statements Shoigu said, "The CSTO must be ready for a possible penetration of terrorists from the territory of Afghanistan," calling on the CSTO to prepare for the militant’s invasion. The dominant message in many articles published by various military and security experts is that there are sleeping terrorist cells in all Central Asian countries, that the Taliban are going to create a jihadist terrorist dictatorship that has far reaching plans for the region and that there is no one but Russia to defend them from inevitable threats.

The deteriorating situation in Afghanistan will become a serious test for the CSTO, which will have to prove that it is capable of being the security guarantor in the region, especially when its reputation was seriously hit by the latest Armenia-Azerbaijan and Tajik-Kyrgyz conflicts. In Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, the political establishments were strongly dissatisfied with the fact that Russia did not fulfill its commitments as their strategic partner.

Meanwhile, the pro-Russian authoritarian regimes of the region are trying to extract their own advantages from the events in Afghanistan, explaining to their populations that without a strong hand and political stability, their countries will risk turning into another Syria, Iraq or Libya. For example, in Tajikistan, where the current president is attempting to transfer power to his son, and which is the most vulnerable country to terrorist infiltration and the only country who openly opposed the Taliban, President Rahmon successfully uses the terrorist and nationalistic cards to unite his people against one enemy. It’s clear that he is doing this in order to preserve power, increase the level of his legitimacy in the eyes of the Tajik population by creating an image of a person who cares about Tajiks not only within its country, but also abroad. This has attracted even his opponents to his side.

Finally, a "peaceful border" with Central Asia will also open another opportunity for trade and economic cooperation. A stable Afghanistan will allow Russia to reach the Indian Ocean, benefit from the potentially feasible TAPI project, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline with a capacity of 33 billion cubic meters per year, allowing Gazprom to enter the huge markets of Pakistan and India, as well as to sell Russian products, such as weapons, trucks or grain.

Both China and Russia seem to share similar visions and a model of cooperation and complementarism where Russia takes the role of the security and weapons provider for the regional countries while China deals with economic development, trade and investments. Both countries are deeply concerned about the problem of the “terrorist emmigration” due to the possible influx of Islamic extremists from Afghanistan, so they seek to preserve stability and are not interested in the disintegration of Afghanistan. The Taliban is not a problem as long as it operates within Afghan borders, doesn't harbor international extremists, and doesn't engage in drug trafficking.

Previous experience has shown that when the U.S. invades and then withdraws its troops from a country, it leaves behind complete chaos. All the preconditions exist to transform Afghanistan into a new Syria through prolonged civil conflict and competition between different fractions backed by numerous regional players, as it is not certain that the Taliban will be able to keep the monopoly of power and will be challenged by the more uncompromising and extremist groups since they no longer have a common external enemy.

But even if the the Taliban colludes with all those extremest groups and completely changes its foreign course and ambitions, both scenarios can potentially sabotage China's "One Belt, One Road" project in the region, restricting its access to the region’s natural resources and transit of Chinese exports through the potentially lucrative corridors. It will also potentially weaken Russia's influence in Central Asia, exacerbate the conflict between Pakistan and India, and destabilize Iran with a domino effect as Afghanistan is not just a battlefield between the Pashtuns and other ethinc, religious and political minorities, different flows within the Taliban, between the U.S. and Russia, the U.S. and China, but also involves the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India and China (as Pakistan's key ally), Iran and the monarchies of the Persian Gulf, therefore Shiites and Sunnis in the Greater Middle East.

Therefore, the success of the policies of different countries directly or indirectly affected by the Afghan events, including Armenia, will largely depend on their abilities to understand, assess and respond to the chaotically changing environment.

Also see

Was China All Innocent During the 2020 Artsakh War?

By Paruyr Abrahamyan

China considers Turkey a key strategic partner under the Belt and Road Initiative. It has also intensified economic relations with Azerbaijan and is keen to diversify its commercial routes to Europe. Was China a silent observer or did it have any role to play during the 2020 Artsakh War.

What Is France Looking for in the Nagorno-Karabakh Issue?

By Gaïdz Minassian

Since the 2020 Artsakh War, France has been at the forefront of diplomatic activity in resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. What goal is Paris hoping to achieve with this issue that is so far removed from the concerns of the French?

Why Is Armenia Terrible at Foreign Policy? The Failure of Multi-Vectorism and the Need for a New Doctrine

By Nerses Kopalyan

Armenia’s defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War was a collective failure of all state bodies and institutions. The new Armenian government must construct a foreign policy doctrine defined by “strategic engagement.”

CSTO Failing At Its One Job

By Areg Petrosyan

Armenia will be looking to take advantage of its chairmanship of the CSTO to create a new Crisis Response Center. If its supposed allies continue their indifference even at the organizational stage, they should all be asking themselves why they are together in the first place.

A White Paper to Build a Security Architecture

By Tigran Yegavian

What has Armenia’s defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War revealed? Tigran Yegavian reviews a recently published White Paper that looks at a number of misconceptions, failures and dysfunctions within Armenian statehood and attempts to diagnose those ills and offer possible solutions.

Who Is Responsible For the 2020 Defeat?

By Gaïdz Minassian

Gaidz Minassian delves into the turbulent spaces of history, memory and identity and deconstructs why the mother of all battles—the construction of a State on its sovereign pillars—was undermined.

The Escalating Tensions Between Iran and Azerbaijan

By Hranoush Dermoyan

Since the end of the 2020 Artsakh War, tensions between the Islamic Republic of Iran and Azerbaijan have been escalating. Although an outright military confrontation seems unlikely, it would have devastating consequences for the region.

Who Is Armenia’s Peace Partner?

By Tatevik Hayrapetyan

Azerbaijan and Turkey are not interested in peace. With the new realities on the ground following Azerbaijan’s military success, the Armenian Government should be careful when promising an “era of peace” to its people.