Illustration by Armine Shahbazyan.

Before the 2020 Artsakh War, several popular myths - widely held beliefs or ideas that are actually false - had become deeply entrenched in Armenian society. These myths revolved around the strength of Armenia’s armed forces, the inherent weakness of the enemy, and Russia as protector of Armenia’s national security interests. But starting on the morning of September 27, 2020, these myths, which had developed over the years and laid deep roots throughout Armenian society, began to crumble with each passing day of the war.

As it became clear that the intense bombing and widespread ground attack against Artsakh was not going to end in a matter of days, the first myth to fall was that Russia would never allow Azerbaijan to conduct an extended war with Armenia. Even the leadership of Armenia at the highest levels believed this to be the case. Admittedly, this myth had grounds in that the longest armed clash between Armenia and Azerbaijan after the ceasefire in 1994 was the 2016 Four Day April War, which also ended with a ceasefire brokered by Russia. However, 2020 proved that Russia was very much willing to allow Azerbaijan to wage widescale war in the Caucasus against Armenia - Russia’s strategic treaty partner. Although President Putin was engaged with both sides during the entirety of the conflict, Russian attempts to stop the war in its early phase were not successful, contrary to what a large segment of Armenian society had come to expect.

That this myth was entrenched in Armenian society, from top to bottom, proved to be disastrous because it likely disincentivized Armenia’s leadership from preparing for an intense and extended war, wishfully believing that after a few days Russia would inevitably step in to put an end to any conflict. It is safe to say that this myth is now completely debunked as Armenians have learned that they were woefully mistaken regarding Russia’s allegiances and policy regarding war in the region.

As the war pushed into weeks two and three, Armenians who were paying attention beyond the “We Will Win” (hakhtelu enk, in Armenian) slogan or had direct information from the front lines, had to accept that Azerbaijan had superior firepower and was making sizeable and irreversible territorial gains. For decades and even stretching back to Soviet times, Armenians often claimed that Azerbaijani soldiers are not willing to risk their lives for Karabakh and would fearfully run from the battlefield at the first sign of danger. Given this myth, Armenians never considered it possible that Azerbaijan could conduct an effective and organized war campaign. As with other pre-war myths, Armenians were forced to reassess this one as Azerbaijan advanced deeper and deeper into Artsakh. Yet, unbelievably, there are those who still insist on hanging onto this myth despite the war’s result. The justification now used is that Azerbaijan was only able to prevail because of Turkey’s significant military assistance. Although it is true that Turkey provided direct assistance to Azerbaijan in this war, for those who are objective, Azerbaijan’s own military achievement and successes cannot and should not be discounted. Regardless, Armenians should have known better than to habitually violate a tenet of warfare: never underestimate the enemy.

Another previously popular myth in Armenia, held even by the top echelon of leadership who as we learned after the war had direct information to the opposite, was that the Armenian army was the most battle-ready (martunak) in the region. This was a statement that Armenians heard over and over again throughout the years by all leaders, civilian and military. Only months before the war, Armenia’s then-Defense Minister Davit Tonoyan even proposed a new doctrine – new war, new territories – meaning that if Azerbaijan launched a war, Armenia would move beyond its defensive posture and shift the battle onto Azerbaijani territory. The honest, yet naive, belief in Armenia was that Azerbaijan would never be able to take back land by force. The war clearly showed that this assessment was a myth. The war proved that the Armenian military was not ready organizationally, strategically, nor tactically for the modern type of warfare that was unleashed on September 27, 2020. This myth seems to have lulled even those in charge of Armenia’s and Artsakh’s national security into believing that the armed forces were much more battle-ready than they proved to be in the heat of battle.

Although the old myths must be discussed and dispelled, it is disconcerting the speed with which new myths are being constructed and spread. If these new myths become as deeply entrenched as the pre-war myths, Armenia again risks fooling itself into disingenuous politics and disastrous policy.

Armenia lost the 2020 Artsakh War. There cannot be two ways about it. Whether Azerbaijan won as completely as it had hoped is open to debate. That Azerbaijan was directly assisted by the Turkish military or that paid foreign mercenaries from Syria were utilized doesn’t change the fact that Armenia lost the war, plain and simple. Why or how Armenia lost is, of course, an entirely appropriate and necessary topic for deep and serious discussion and investigation. But the reason Armenia lost cannot cover for the fact that Armenia lost. The most glaring proof of loss is that, in addition to relinquishing the seven regions surrounding the Soviet-era Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), Armenia also gave up two other key areas which had been in the NKAO - the entire region of Hadrut and the historically, strategically and symbolically important city of Shushi. Sure, Armenia didn’t relinquish 100% of Artsakh, but that is only because Russia stepped in to prevent Azerbaijan from advancing any further in order to ensure the deployment of Russian peacekeepers. Yet, less than three months after the end of the war, there is already talk from a significant number of people in Armenia that the country didn't lose the war. This conclusion can be heard in casual conversation and from talking heads, including members of parliament, who appear on TV.

There are several accompanying justifications for this new developing myth. One is that Armenia fought valiantly for 44 days against the might of several countries, including Azerbaijan, Turkey, Israel and Pakistan. While true that the outgunned and outnumbered Armenian soldiers fought bravely, it is difficult to understand how this changes the fact that Armenia lost the war. The war, after all, was for territory, which Armenia lost in large swaths, and the security of Artsakh, which is now guaranteed by Russian, not Armenian, forces. War is not the venue for moral victories. Maybe in sports a strong performance in a loss can still serve as encouragement for a team’s next game, but when it comes to war, although countries must prepare, the hope is that the “next game” is never actually played. Looking to assess the outcome of the 2020 Artsakh War from another angle, it’s worthwhile to consider that there have been wars that are widely accepted to have ended in a stalemate. Such was the Iran-Iraq War, which lasted for eight years without neither side conquering any new territory. The 2020 Artsakh War, on the other hand, was obviously not a stalemate – meaning one side was victorious, while the other was defeated. In order to properly prepare for any new war which may be waged upon Armenia, it is crucial to not hide from this uncomfortable but essential truth. Otherwise, the country once again risks lulling itself into a sense of false security based on myths stemming from faulty analysis and outright denial of facts.

Yet another myth that is currently starting to make its way through Armenian society is that the Russian troops will never leave. Journalist Tatul Hakobyan methodically dispelled this myth in an article published on February 2, 2021. He gives several examples of Russian troops withdrawing from previously deployed areas, often to Armenia’s detriment. From 1915-1918, on two separate occasions, Russian troops pulled back from the Armenian provinces in Anatolia and the Caucasus. Especially catastrophic, Hakobyan writes, were the pullbacks from May to June 1918, which devastated Armenians in Van, Erzurum and Aleksandrapol. Next, he writes that the First Karabakh War began when the then-Soviet troops pulled out of Artsakh toward the end of 1991 and beginning of 1992, creating the space and opportunity for the ensuing bloody war.

The reason for this new myth is simple: it provides a sense of comfort and security to believe that Armenians in Artsakh will be forever protected from Azerbaijani aggression due to the presence of Russian troops. This myth, however, is very dangerous and could cause great harm to Armenians once again in the not so distant future because according to Article 4 of the November 10, 2020 ceasefire statement, Russia's peacekeeping mandate in Artsakh is initially for a five-year period. If neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia object to the presence of Russian troops within six months of the expiration of this initial five-year period, the mandate is automatically extended for another five years. In the upcoming years, if this myth gains traction in society and the government, Armenia risks being dangerously unprepared in the event Russia is asked, forced or decides to leave due to domestic or geopolitical factors that may exist in 2025. History shows that Russia has withdrawn its troops before from lands inhabited by Armenians, which means it can happen again. Armenia must prepare for this eventuality, while simultaneously working to have the Russian forces stay as long as necessary.

For every Armenian that lived and breathed the 44-day war, let alone those that actually fought or were in the war zone, those were the most tense and painful 44 days of their lives. Each 24 hours felt excruciatingly longer. Even one day of war is hell, let alone a month and a half. However, Armenians must not ignore the fact that there have been many intense and cruel wars on this planet that are measured in years, even decades – not months or days. Armenian society should not fool itself into believing the 44-day war was a long war, lest a truly long war is unleashed and the country is once again unprepared. Let’s look at some examples. The Vietnam War went on for a seemingly endless 20 years, from 1955 to 1975. The Iran-Iraq War, as previously mentioned, began in 1980 and took eight years to resolve. The Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979 and didn’t leave until 1989, some ten years later. World War I lasted four years, World War II six years. Even the First Karabakh War raged for over two years, after full-scale fighting erupted in 1992. So, in comparison, the 2020 Artsakh War was glaringly short. Yet, the myth that is now being formed in Armenia, without much thought, comparison or analysis, is that the 2020 war was a long one. The common saying is something to the effect of “We fought 44 days against much more powerful forces.” If Armenians begin to firmly believe that 44 days of war is long, turning this belief into a myth, the country again risks not having sufficient war materiel and other necessary rations in case of a much longer conflict. One major shortcoming during this war was that Armenia’s supplies, from basics such as helmets and flak jackets to heavy weaponry and munitions, were in woefully short supply. Armenian citizens must anticipate that the next war will be much longer than 44 days and hold accountable any government that does not properly prepare the country for such a war in the future.

Armenia is not a unique country when it comes to the myths it creates and propagates about itself. Every country creates myths to promote a sense of national unity and pride. Yet, for a small and still developing country like Armenia, making essential policy decisions based on myths proved to be bloody and costly given the limited demographic and financial resources of the country.

also read

Postmortem of a Catastrophe

By Nerses Kopalyan

Will the formation of a Truth Commission on the 2020 Artsakh War make it possible to rectify persistent and systemic errors that led to such military and geopolitical failures?

12 Imperatives for Securing Armenia’s Future

By Raffi Kassarjian

We have a maximum of five years to significantly improve the security of the country along a number of fronts, requiring a collective will, sacrifices, trade-offs and personal choices unlike anything most of us have faced in our lifetimes, writes Raffi Kassarjian.

Short to Mid-term Steps for Post-War Armenia

By Artin DerSimonian

Armenia can either unify around a shared vision for the future or digress into internal political strife. Artin DerSimonian explores what a unified Armenian vision for the future could include if the country is to continue on the path of healthy socio-economic development.

Can Trade Prevent War?

By Artin DerSimonian

Given the growing sense of global multipolarity and the apparent twilight years of the American-anchored liberal international order, Armenia cannot solely rely on friends and allies around the globe to ensure its survival. A more realistic approach is necessary.

Should Armenia Align With Stateless Nations?

By Seda Hakobyan , Alexandre Solano

This opinion piece argues that Armenia can pursue a strategy that can lead to the defense of democracy with respect to the right to self-determination of peoples by aligning itself with other stateless nations.

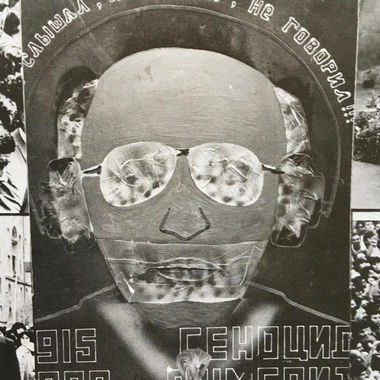

The Slogans, Posters and Language of the Karabakh Movement

By Harutyun Marutyan

One of the distinctive characteristics of the Karabakh Movement was that in less than three years, it drastically changed how the Soviet value system was perceived. The visual and verbal manifestation of this was evident through the transformation of the language and texts of the posters and signs used during the Movement.