Sat Aug 15 2020 · 5 min read

It Has To Be Said: A Century of Disruption and Fracture

By Maria Titizian

The great dispersion of the Armenian people, as a direct consequence of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, has led to a continuous cycle of disruption and fracture for almost every generation since. We know the story too well. Many of the survivors ended up in Syria, Lebanon and beyond. Bearing the calamitous loss of loved ones, lives, heritage, culture and homeland, they tried to rebuild their lives on foreign shores.

Through a labyrinthine journey, my survivor-grandparents from Marash, Urfa and Musa Ler ended up in Beirut, the city where my parents met and started their own lives. The old black and white photos of 1960s Beirut my mother kept in a tin cookie box mesmerized my childhood. But alas, my father, sensing that there would be no future for his children there, decided to embark on another journey. He applied to two countries for residency: Canada and Australia. Whichever accepted him first would be the country he would move his family to. We arrived in Toronto in March 1968. Images of my sister and I bundled up in heavy winter coats, handknit hats and scarves covering our faces live in my memories. And we lived, barely. My parents, children of genocide survivors, never had many prospects. They left behind their parents, siblings and friends and arrived in Canada with almost nothing - no money, no education, no family or support network.

In 1975, the Civil War broke out in Lebanon. And thus began a procession of aunts and uncles and cousins escaping the ugly sectarian violence in their country of birth, a generation after their parents had also been forced to leave their own ancestral homeland.

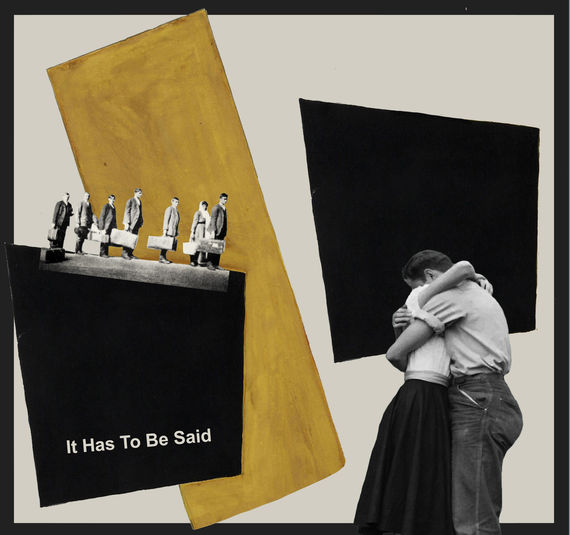

My earliest memories are of going to the airport to pick up one family after another. My paternal uncle Dikran, his wife Knar and their son. My other paternal uncle Armen, his wife Maro and their sons. One of my two paternal aunts, Armenuhi and her family. My oldest maternal uncle Apraham, his wife Mary and their two children.

Among the last to arrive was my maternal grandmother, aunt and youngest uncle. I remember the butterflies in my stomach as a child in the back seat of the car as we headed to the airport. I had never felt the unrelenting love of a grandparent and I made myself physically sick at the thought of finally having one. Staff at the airport were on strike and I recall arriving at the empty terminal with my family. We walked into the strangely quiet building, looking for them. Then I saw a young man running toward my mother with flailing arms. It was my uncle. They hadn’t seen each other in eight years. He threw himself into her waiting embrace. Then my aunt and grandmother, exhausted and broken, came into view. The family was finally, if partially, reunited. Even now, I can feel the joy and relief that swirled around us as we stood in the deserted halls of the airport terminal.

So much of my childhood was witnessing my parents welcoming their brothers and sisters and their families into our home, a home which had been so lonely before was now full of relatives. Our cramped overstore apartment became a station for the weary refugees of the Lebanese war.

The years moved on, more disruption. The revolution in Iran brought more Armenians to Toronto and, for the first time in my life, I heard Eastern Armenian being spoken with its lyrical intonations. On the heels of the revolution, Iraq invaded Iran, leading to almost eight years of what came to be known as the Iran-Iraq War. It, too, brought more Armenians escaping someone else’s war to our faraway shores.

The years moved on. The Soviet Union began falling apart, the Berlin Wall came down and as the Armenian nation began fighting for the reunification of Karabakh with Armenia, tens of thousands of Armenians in Azerbaijan were forced to flee. Mobs of marauding Azerbaijanis attacked ethnic Armenians in Baku, Sumgait, Maragha and elsewhere, sometimes dragging them from their homes into the streets and brutally murdering them in broad daylight. In between the rallies for reunification, the pogroms, the hopeful uncertainty, the massive Spitak earthquake hit. In the midst of this chaos, the lost homeland became the found homeland. And as Armenians of Armenia began emigrating to escape the despair and destruction, another generation in the diaspora (albeit only a handful at first) uprooted themselves and moved across the ocean again.

The story of my family is the story of the nation. Constant uprooting, constant disruption, a never-ending cycle of pain, tragedy, loss, of never belonging. Our move to Armenia, however, wasn’t about escaping something; it was about running toward something - a homeland, somewhere where we thought we could belong, where we believed we could be an integral part of the fabric of society. While we did our best to integrate, some days I feel like we are still “the other” even here and lately, even there, where we came from. But it is the one place where we feel a little less of an odar (foreigner) than anywhere else.

As I continue to obsess about the situation in the Middle East and the Armenians living there, my remaining paternal aunt’s family in Lebanon is now at a crossroads following the catastrophic explosion at the port of Beirut. Her grandson is now coming to join us in the motherland. Yet another tragedy ripping our people apart, while bringing them together again.

I often wonder if it's our fate - to be forever roaming the earth, in search of home, belonging, safety, security. I hope that my conscious disruption, conditioned by our move to the homeland almost 20 years ago, will be the last and that the generations that come after us will no longer have to run away from someone else’s hatred and inhumanity, from someone else’s war. My earnest hope is that this cycle will be the last, that in the embrace of the eternal mountains of the Republic of Armenia, my family and many others like ours will find the safe harbor they have been searching for since being uprooted over 100 years ago.

Last Week's Editorial